PRACTICE (2023 Edition) 2023 Edition Volume 7 Table of Contents Page Editorial Board of Reviewers 3 Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion: An Evaluation of University/College 5 Teacher Preparation and Inclusion Courses Cordelia A Yates and Carolyn Glackin Efforts to Recruit and Retain Special Education Teachers in One Southern State 30 Kelly E. Standridge, Jocelyn E. Belden, Elizabeth W. Colquitt, Robert C. Hendrick, Jonté A. Myers, and David E. Houchins Exploring Post-Secondary Transition Preparation for Students with Disabilities 58 Emily N. Smith and Braelyn R. Ringwald The Special Education Teacher Shortage: A Policy Brief Alyssa Sanabria Experiences of a Student with Deaf-Blindness in Community-Based Rehabilitation 77 and Disabilities Studies Unit in the University of Education, Winneba Emmanuel K. Acheampong and Rabbi Abu-Sadat Analysis of Syntactic Complexity and Its Relationship to Writing Quality in 89 Argumentative Essays using an Automated Essay Scoring Webtool Thilagha Jagaiah, Natalie Olinghouse, Devin Kearns, and Gilbert Andrada 2023: Special Education Research, Policy and Practice (SERPP) 1

SPECIAL EDUCATION RESEARCH, POLICY &

2023: Special Education Research, Policy and Practice (SERPP) 2

Most Impactful Element of Preschool Early Intervention Services on 111 Kindergarten Readiness: Instruction with Typically Developing Peers Shannan Smith and Deana J. Ford Measuring the Implementation of Inclusive Strategies in Secondary 122 Classrooms Using an Observation Rubric Randa G. Keeley, Rebecca Alvarado-Alcantar, Maria Peterson-Ahmad, and Paul Yeatts The Shift to Online Engagement for a Post-Secondary Transition Group 135 of Students with Intellectual Disabilities and Autism Emily R. Shamash and Alyson M. Martin Author Guidelines 146 Publishing Process 147 Copyright and Reprint Rights 148

The

Editorial Board of Reviewers

All members of the Hofstra University Special Education Department will sit on the Editorial Board for the SPECIAL EDUCATION RESEARCH, POLICY & PRACTICE. Each of the faculty will reach out to professionals in the field whom he/she knows to start the process of building a list of peer reviewers for specific types of articles. Reviewer selection is critical to the publication process, and we will base our choice on many factors, including expertise, reputation, specific recommendations and previous experience of a reviewer.

Editor

George Giuliani, J.D., Psy.D., Hofstra University

Hofstra University Special Education Full-Time Faculty

Elfreda Blue, Ph.D.

Stephen Hernandez, Ed.D.

Gloria Lodato Wilson, Ph.D.

Mary E. McDonald, Ph.D, BCBA-D, LBA

Darra Pace, Ed.D.

Diane Schwartz, Ed.D.

Editorial Board

Mohammed Alzyoudi, Ph.D., American University in the Emirates. Dubai. UAE

Faith Andreasen, Ph.D.

Vance L. Austin, Ph.D., Manhattanville College

Amy Ballin, Ph.D., Walker Solutions

Heather M. Baltodano-Van Ness, Ph.D., BCBA-D, University of Nevada, Las Vegas

Dana Battaglia, Ph.D., CCC-SLP, Westbury UFSD

Brooke Blanks, Ph.D., Radford University

Kathleen Boothe, Ph.D., Southeastern Oklahoma State University

Nicholas Catania, PhD, State College of Florida, Manatee-Sarasota

Lindsey A. Chapman, Ph.D., University of Florida

Morgan Chitiyo, Ph.D., University of North Carolina at Greensboro

Jonathan Chitiyo, Ph.D., University of Pittsburgh at Bradford

Heidi Cornell, Ph.D., Wichita State University

Lesley Craig-Unkefer, Ed.D., Middle Tennessee State University

Amy Davies Lackey, Ph.D., BCBA-D

Lauren Dean, Ed.D., Hofstra University

Josh Del Viscovo, MS, BCSE, Northcentral University

Darlene Desbrow, Ph.D.

Janet R. DeSimone, Ed.D., Lehman College, The City University of New York

Lisa Dille, Ed.D., BCBA, Georgian Court University

William Dorfman, B.A. (MA in progress), Florida International University

Brandi Eley, Ph.D.

Tracey Falardeau M.A., M.S., Midland Educational Agency

Danielle Feeney, Ph.D., Ohio University

Neil O. Friesland, Ed.D., MidAmerica Nazarene University

2023: Special Education Research, Policy and Practice (SERPP) 3

Theresa Garfield, Ed.D., Texas A&M University-San Antonio

Leigh Gates, Ed.D., University of North Carolina Wilmington

Sean Green, Ph.D.

Mohammed Hamzeh Al Zyoudi, Professor

Deborah W. Hartman, M.S., Cedar Crest College

Shawnna Helf, Ph.D., Winthrop University

Nicole Irish, Ed.D., University of the Cumberlands

Randa G. Keeley, PhD, Texas Woman's University

Hyun Uk Kim, Ph.D., Springfield College

Louisa Kramer-Vida, Ed.D., Long Island University

Nai-Cheng Kuo, PhD., BCBA, Augusta University

Renée E. Lastrapes, Ph.D., University of Houston-Clear Lake

Debra Leach, Ed.D., BCBA, Winthrop University

Marla J. Lohmann, Ph.D., Colorado Christian University

Mary Lombardo-Graves, Ed.D., University of Evansville

Pamela E. Lowry, Ed.D., Georgian Court University

Denise Lucas, M.S.

Matthew D. Lucas, Ed.D., Longwood University

Jay R. Lucker, Ed.D., Professor Emeritus, Howard University

Jennifer N. Mahdavi, Ph.D., BCBA-D, Sonoma State University

Alyson Martin, Ed.D., Fairfield University

Krystle E. Merry, M.S. Ed., NBCT., Ph.D. Candidate, University of Arkansas

Marcia Montague, Ph.D., Texas A&M University

Chelsea T. Morris, Ph.D., University of West Georgia

Gena Nelson, Ph.D., University of Oregon

Lawrence Nhemachena, MSc, Universidade Catolica de Mozambique

Maria B. Peterson Ahmad, Ph.D., Western Oregon University

Christine Powell. Ed.D., California Lutheran University

Deborah Reed, Ph.D., University of Tennessee

Ken Reimer, Ph.D., University of Winnipeg

Dana Reinecke, PhD, BCBA-D, Capella University

Denise Rich-Gross, Ph.D., University of Akron

Benjamin Riden, ABD -Ph.D., Penn State

Mary Runo, Ph.D., Kenyatta University

Emily Smith, Ed.D., University of Alaska

Carrie Semmelroth, Ed.D.., Boise State University

Pamela Mary Schmidt, M.S., Freeport High School Special Education Department; Robert F.

Kennedy Human Rights, Lead Educator

Edward Schultz, Ph.D., Midwestern State University

Mustafa Serdar Köksal, Ph.D., Hacettepe University, Turkey

Emily R. Shamash, Ed.D., Fairfield University

Christopher E. Smith, PhD, BCBA-D, Positive Behavior Support Consulting & Psychological Resources

Emily Smith, Ed.D., Midwestern State University

Gregory W. Smith. Ph.D., University of Southern Mississippi

Emily Sobeck, Ph.D., Franciscan University

Ernest Solar, Ph.D., Mount St. Mary’s University

2023: Special Education Research, Policy and Practice (SERPP) 4

Gretchen L. Stewart , Ph.D., University of South Florida

Roben Taylor Daubler, Ed.D., Western Governors University

Jessie Sue Thacker-King, Arkansas State

Julia VanderMolen, Ph.D., Grand Valley State University

Joseph Valentin, Ph.D.

Nancy Welsh-Young, Ed.S., Ph.D. Candidate, University of Arkansas

Cindy Widner, Ed.D., Carson Newman University

Kathleen G. Winterman, Ed.D., Xavier University

Sara B. Woolf, Ed.D., Queens College, City University of New York

Mohamed Bin Zayed, University for Humanities

Perry A. Zirkel, Ph.D., J.D., LL.M., Lehigh University

2023: Special Education Research, Policy and Practice (SERPP) 5

Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion: An Evaluation of University/College Teacher Preparation and Inclusion Courses

Dr. Cordelia A Yates Dr. Carolyn Glackin

Morningside University

Abstract

Within the diverse classrooms in the United States, there remains a gap in student performance, reflecting issues of inequity and inclusion. Within this context, the purpose of this mixed methods study was to evaluate the effectiveness of university/college teacher preparation inclusion courses from the perspectives of beginning K-12 special education and general education teachers prepared in traditional and alternative teacher education programs. With a total of 34 participants completing the study, the quantitative findings suggest that K-12 special education and general education teachers were generally satisfied with their teacher preparation in traditional and alternative teacher education programs. Within the analysis of the qualitative results, participants expressed that the skills provided within the preparation programs helped provide general knowledge to support students within a diverse classroom. However, participants simultaneously expressed that gaps remain in how to apply the skills learned within education programs to the complex real-world context of the classroom.

Keywords: Inclusion, diversity, equity, teacher preparation, teacher education

Introduction and Purpose

The United States is recognized across the globe as an epitome of a democratic society that champions the world on human rights issues which range from socio-economic, political, cultural, and educational issues. However, American society has not been able to completely rid itself of these related issues, especially in providing equitable and equal education for all its citizenry. For example, different scholars have identified the demographics of societal classrooms as heterogeneous, mimicking the multicultural diversity of the nation’s populace (Grant & Gibson, 2011); like school classrooms that are made up of students with disabilities, English Learners, African Americans, minority groups and immigrants from across the globe (Roose et al., 2019; Villegas & Lucas, 2002). Corroborating this, current national education statistics from 2019 to 2020 stated that the number of children who received special education services was 7.3 million (National Center for Education Statistics), and the percentage of English learners in public schools across the nation was 5.0 million.

Given the diverse nature of our classrooms and the high percentage of students who require proper education to be at par with higher performing students (Hatton, 1995; Roose et al., 2019; Zeicherner, 1983), how have the nation’s institutions of higher learning prepared teachers to take up these challenges, specifically in addressing the issue of inclusion and equity? (Milner, 2010). Additional issues include the following questions: Who gets educated and who does not? What are the educational gaps that have continued to persist because of inadequate preparation of

2023: Special Education Research, Policy and Practice (SERPP) 6

teachers in the nation’s universities and colleges (Darling-Hammond, 2002)? What should be the focus of teachers’ preparation programs, and how can teachers learn the cultural background and perspectives of students to build teaching practice that is relevant to all and not a few (Loewenberg & Forzani, 2009)?

These controversies have not only formed the foundation of inclusive movements in education but also brought to the forefront the inclusive courses created by universities and colleges. These courses are intended to develop teachers’ abilities to teach in diverse classrooms. Inclusive courses were developed to help teachers learn teaching strategies that would help them to educate all children no matter their disabilities, or social or cultural backgrounds (Jelas, 2010). In addition, education professionals and policymakers in the nation have acknowledged these needs by arguing for effective centralized development of teachers’ skills and standards that would empower the nation’s teachers in diverse classroom practice (Burns & Shadoian-Gersing, 2010; Darling-Hammond, 2010; Kumar et al., 2018; Linder et al., 2019; Prasetyo et al., 2021).

Teachers’ understanding of students’ cultural backgrounds is crucial in consideration of the fact that more than 90% of both special and general education teachers in society are white (Kumar et al., 2018; Smith, 2009). It becomes increasingly necessary to emphasize multicultural education in university and college teacher preparation programs (Bell, 2002; Goldenberg, 2014) to be able to achieve equitable and inclusive education for all students (Goldenberg, 2014; Prasetyo et al., 2021; Solomona et al., 2005). In addition, reinforcing multicultural study and ethnic understanding in teachers' university and college education will develop in teachers the awareness to examine their personal biases to challenge their linguistic dominance and color blindness (Haddix, 2008; Kumar et al., 2018).

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the effectiveness of university /college teacher preparation inclusion courses from the perspectives of beginning K-12 special education and general education teachers prepared in traditional and alternative teacher education programs. The questions explored in this study were as follows:

1. How do teachers describe the courses they studied in the university that prepared them to teach in the inclusion classroom?

2. How do teachers describe the specific skills they acquired from the inclusion course they took in the university in terms of preparation to handle students with and without disabilities?

3. How do teachers describe the impact of the university/college inclusion course(s) they studied on their current classroom practice?

4. How do teachers assess the quality and effectiveness of their current practice based on the university/college inclusion coursework they took?

5. Do teachers feel their university education inclusion course adequately prepared them to assume the role of an inclusion teacher?

6. What changes do teachers believe are needed in university/college curriculum and instruction inclusion courses?

7. What do teachers believe should be included in teachers’ university education to prepare new teachers for the inclusion classroom?

2023: Special Education Research,

and

7

Policy

Practice (SERPP)

Theoretical Framework

From its inception, the United States of America has been home to diverse populations. This has manifested in an upward enrollment of culturally diverse students in the nation’s schools. The nation’s educational paradigm has continued to focus on the demographics of our classrooms as a priority in teachers’ education preparation programs, (Villegas & Lucas, 2002). A similar trend surrounds the proliferation of the issues of inequality and inequity among different groups in society. For example, students with disabilities who enrolled in the nation’s schools in the 20192020 school year represented 7.3 million of the student population (National Center for Education Statistics, n.d.); a group who to a large extent, has continued to experience an education gap when compared to students without disabilities. In response, the federal government became actively involved by authorizing educational laws and policies intended to thwart the inequities in public schools. Consequently, higher education revamped curricula to reflect the needs of the education system at the time. In other words, preservice courses at higher learning institutions in the United States must include topics on inclusion, access, and diversity (Forlin, 2010).

In acknowledgment of this, Plash and Piotrowski (2006) investigated how university teaching programs were responding to developing preservice teachers for the inclusion classroom. The researchers noted that “Only 27% of the reviewed universities offered at least 3 credit hours explicitly related to the inclusion of students with disabilities. This is surprising given that differentiating instruction benefits all learners, not just students with disabilities” (p. 307). Furthermore, a more recent study carried out by Taylor and Ringlaben (2012) revealed that teachers felt they were not adequately prepared to educate students with disabilities in the general education classroom setting irrespective of the federal Least Restrictive Environment mandate under the IDEA of 1975, (United States Department of Education). Responding to this, Logan and Wimer (2013) stated the following:

future studies should allow teachers to create narratives on their experiences with inclusion including the positives and challenges with suggestions for improving teacher experience. It seems that college special education faculty and school administrators must take the time to have open forums to discuss how to improve inclusive classrooms in their schools and how to improve our college preparatory training programs. (p. 7).

Corroborating the importance of effective university programs to the effective implementation of inclusion in school classrooms, Allday et al. (2013) stated that the feelings of unpreparedness expressed by teachers could be traced to “the number and type of courses related to the inclusion of students with disabilities” (p.308); and expressed the importance of further research study to determine areas of study that teachers believe could help their practice as inclusion teachers. Also, by keeping up with investigations into current practices of inclusion programs, educators are kept in awareness of the “social justice aims of inclusive education that have been previously subverted by the economic concerns tied to assessment practices.” (Gregory, 2018, p.129). In addition, educators must acknowledge that as the issues of diversity and equity continue to wax strong in the nation, and our classrooms in response continue to grow with diverse learners , “More and more researchers are looking at how Higher Education is responding to students with

2023: Special Education Research, Policy and Practice (SERPP) 8

different abilities, or as they are usually called, students with disabilities.” (Morina, CortesVegas & Molina, 2015, p.2).

In retrospect of the stated research findings and observations by different scholars above, it becomes necessary for these researchers to build on the stated past studies by evaluating further the impact of university education inclusion courses on the practices of new teachers of one to two years in public schools, from the perspectives of the special, alternate, and general education teachers. More so, if we understand that the crux of the matter in this discourse is attaining access and equity in classrooms by implementing the principles of inclusion, it brings us to the question: how is this accomplished effectively? Responding to this question, Lancaster and Bain (2019) stated, “Pre-service teacher education programs are the vehicles for providing teachers with the preparation they require to work in inclusive classrooms” (p. 51), thus preservice teacher preparation programs should include curricula that foster learning for all students.

Study Significance and Theoretical Contributions

In today’s society, there are movements of social justice causes headed by different cultural, ethnic, language, and religious diversity, which poses the challenge of a democratic and inclusive practice that would meet the needs of everyone in society ( Roose et al., 2019). This challenge extends to the education of students of diversity in schools and teacher education and their professional roles in diverse classrooms (Vranjesevic, 2014). This challenge is also recognized by different various teacher preparation programs, that in turn are challenged by different philosophical perspectives of teacher education in society and teachers’ personal beliefs and reluctance to understand issues of students from multicultural backgrounds and exceptionalities (Gay, 2015; Sparapani, 1995).

This notwithstanding, the issue of meeting the needs of diverse students in the classroom outpaced any personal idiosyncrasies of a person or any group of people in society. Not unlike many schools around the world, United States schools have continued to be populated with diverse, multicultural, ethnic, and religious groups, which means teachers’ education colleges and universities must make changes to their curriculums to produce teachers that are sensitive to cultural diversity and feel the personal sense of responsibilities to ensuring every student of every background experience a successful education and social outcomes (Liggett & Finley, 2009).

Scholars have alluded to the educational achievement gap between white and non-white students as well as students with disabilities to the rationale that most American school teachers are white and lack the frame of reference necessary to be successful with students of diversity (McFalls & Cobb-Roberts, 2001). Because of this, American educational systems have come under a lot of scrutiny by concerned citizens, different professional bodies, and families. As such, an assessment of educational progress in the United States since the 1980s indicated that the quality of the American Educational System has continued to dwindle and is marked by widened achievement gaps between the United States when compared to other developed nations of the world like Finland, the Netherlands, Singapore, Korea, China, New Zealand, and Australia, (Darling-Hammond, 2009). Some scholars have alluded this to the lack of effective multicultural education in teachers’ college/university education programs and challenged the system to permeate teachers’ education curriculum with multicultural social reconstruction principles

2023: Special Education Research, Policy and Practice (SERPP) 9

(Martin, 1994) so teachers can become more aware and reflective of their practices in consideration of the diverse nature of the United States School classrooms.

Education is fundamental to the development of a nation and how competent the nation can function in the current global market so that only the well-prepared nations’ populace can succeed in the global streams of events. For America to match other world powers or remain on top of the strata in the 21 st-century global market, world space, and technological competitions, the nation needs to invest heavily in the education of its citizenry; and restructure preservice teachers’ university/college education programs to reflect a coherence that provides the right kinds of skills (Russell et al., 2001); a responsibility that has also, been squarely placed in the hands of school teachers to provide effective instruction to the diverse student population in American school classrooms. This means teachers must overcome the challenges of teaching all students irrespective of the language barriers and disability challenges in the classroom, an expectation that includes universities and colleges doing their part by preparing the teachers with viable instructional strategies (Valentiin, 2006).

Despite the stated observations and expressed concerns in many research studies, it appears universities/colleges continued to miss the priority of providing effective skills and robust training in their teachers’ preparation programs for teachers to address the diverse demographics in the 21st-century classrooms, which are defined as inclusive; and perpetuate inequitable practices that educate some but not all, (Roose et al., 2019). Taking the forefront and in acknowledgment of the significance of this issue that places the United States education system in a dire situation, the federal government, at different stages, created laws and education legislations to revamp teacher education; for example, the No Child Left Behind Act of 2001 (NCLB) that was later changed to Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) in 2015 (Federal Department of Education); the Carnegie Education and the Economy study on a ‘Nation Prepared” teachers for the 21st Century (Loewenberg & Forzani, 2009); and pressures from concerned citizens and professional societies that advocated for inclusive classrooms, (Imig et al., 2011).

Inclusive classrooms were advocated for in the context of diversity and believed that the practice would address the issues of equal and equitable access to education for all, acknowledgment and appropriate treatment of minority students and students with disabilities, plurilingualism, and integration of immigrant children (Arnesen & Allan, 2009). Many institutions of higher learning and public schools joined this clarion call and have embraced the inclusion concept. Thus, many public schools, in cognizance of the federal mandates and legislations, established inclusion classrooms that are made up of special education students, English learners, and general education students, which culminated in the need for teachers to acquire the right skills to integrate inclusive strategies in their teaching responsibilities (Peebles & Mendagalio, 2014). These notwithstanding, there remains a need to appraise this acceptance by evaluating the reality of its implementation-which means acknowledging that, for students with disabilities and other marginalized students to benefit from the purpose of inclusion, the special education and general education teachers who are at the forefront of implementing educative programs related to inclusive classrooms must have the relevant skills and training (Hoppey, 2016; McCray & McHatton, 2011).

2023: Special Education Research, Policy and Practice (SERPP) 10

Other problems related to the stated issues include the high rate of teacher attrition after five years of teaching and the importance of buy-in and acceptance of teachers to practice inclusion in their classroom, primarily if we reflect on the research findings by Gill et al. (2009), which revealed that preservice teachers become “progressively more negative towards the inclusion of students with disabilities in the general education classroom setting.” (p. 3). The high attrition rate could also be alluded to as frustrations by teachers as lacking the proper skills that would help them provide effective instructions to align the curriculum and clinical practice in a diverse classroom population (Waddell & Vartuli, 2015).

Education programs must take the lead to ensure teachers are equipped with superior knowledge of inclusion to teach classrooms that are made up of diverse student populations (Allday et al., 2013). In addition, there is a need for the scrutinization of teacher education and “a rigorous research agenda…We need greater commitment on the part of the federal government and professional organizations to fund multi-institutional, longitudinal studies of teacher education.” (Brownell et al., 2005, p. 242).

To find solutions to these problems, we must vigorously attempt to explore the feelings of teachers and how ready they felt prepared. In other words ,“Classroom teachers have much to tell us if we would but listen…do teachers possess sufficient valor to implement strategies taught in general special education courses? Are teachers missing the connection between coursework and the world of practice? These are other areas vying for clarifications, solutions, and future studies.” (Logan & Wimer, 2013, p. 7). Furthermore, “An overview of practices in inclusive education can inform stakeholders of the status of inclusive education, describing the contextual factors which affect program implementation, and make recommendations of practical start-up or improvement steps for inclusive education program.” (Tahir et al., 2019, p. 17).

The debate about the preparedness of teachers to practice equity and be culturally responsive in inclusive classrooms has continued to dominate educational discourse around the globe, including in the United States of America, more than ever before. Agreed, schools are embracing the idea that universities or colleges are training teachers. However, “the role, value and relevance of university-based teacher education are being questioned at a time when the movement of people is changing the demographics of schooling and inequities are expanding.” (Florian & Camedda, 2020, p. 4).

Furthermore, “Students with social identities positioned as different from the reference norm (e.g., disabled, non-white, non-binary, etc.) experience various inter-connected forms of systematic oppression that relegate them to the physical and social margins of schools.” (Siuty, 2019, p.38). The implications of these are that we cannot relent as a society and as educators until true inclusion is in total practice. We must continue to evaluate and reevaluate our programs through the process of inquiry and research by reviewing the practices in the field from the perspectives of teachers who are at the forefront of implementing the inclusion programs.

Method

The purpose of this research study was to evaluate the effectiveness of inclusion courses in teacher education at four-year universities from the perspectives of first and second-year teachers

2023: Special Education Research, Policy and Practice (SERPP) 11

in general, alternative, and special education classrooms in k-12 public schools. The expected outcomes were as follows:

1. The expectation is to determine if there would be a need to increase the number of credits of the inclusion courses and the content taught in the universities or colleges

2. If there would be a need to review the course content to reflect multiple courses

3. If there would be a need to restructure current instructional strategies in teaching identified courses that emphasize skills infield practice.

4. If there would be a need to build a foundational understanding in teacher education of cultural and environmental differences that impact students’ learning.

The inclusion courses were created in universities or colleges in response to societal outcries of exclusionary practices to segregate students with learning disabilities in K-12 classrooms. The root cause of these practices was ascribed to teachers’ lack of skills to integrate students with disabilities and without disabilities in the same classroom environment. It is anticipated that by developing inclusion courses and educating teachers on the principles of inclusion, teachers would be able to take on the challenges of managing an inclusion classroom and establishing equitable practices that will help all students to belong and be successful in academic and social outcomes (Stites et al., 2018).

A mixed methods approach was used to add value to the predominantly qualitative research study (Creswell, 2014). The use of mixed method research offered a deeper understanding of the phenomenon, authentication, and credibility as the method allows the triangulation of information (Caruth, 2013; Doyle et al., 2009). By using the mixed method of research, the researchers in this study explored the different perspectives of their research participants and unveiled the relationships that exist between the many research questions (Shorten & Smith, 2017).

Participants

The participants in this study were a random sampling of 34 public school teachers recruited from different public schools located in the mid-western state of Iowa in the United States. The researchers’ goal was to survey approximately 50 teachers with one to two years of experience in their teaching careers. However, even with the use of the snowball sampling technique to reach the intended sample size, only 34 participants responded by completing the questionnaire that was sent out via emails, using the snowballing technique of referrals to reach the sampled population.

The snowballing sampling technique has been used in qualitative and social science research to access hard-to-reach sample populations and is considered effective for gathering data in research (Hancock & Gile, 2011). The snowballing method has been validated as an effective technique that can yield important research data, which includes social knowledge and power relations (Biernacki & Waldorf, 1981). Furthermore, snowballing has the advantage of lower cost in terms of transportation, which made it convenient for the researchers to select this method as it saved them a lot of travel costs and other financial responsibilities that would have been incurred to travel around different cities within the State of Iowa to reach their participants. In consideration of the highlighted benefits, the researchers using the snowballing method were

12

2023: Special Education Research, Policy and Practice (SERPP)

able to survey their research participants using contact information that was provided by other informants (Naderifar et al., 2017).

The first step the researchers took to access the sampled population was identifying key personnel within their department of education at Morningside University, with Dr. LuAnn Haase, who was retiring as a dean. Because she was retiring, she had a secondary position as the Initial Intern MAT Program Coordinator. The program Coordinator sent out several emails to her contacts across the school districts in Iowa introducing the researchers and explaining the purpose of their research in the emails and asking for assistance on their behalf to link up teachers that fell within their sample population.

The second step the researchers used to collect their data was to send out emails to Iowa’s nine Area Education Agencies (AEA). The email included a brief description of the study and a request for emails of teachers that fit the target population. Two out of the eleven responses resulted in a total of 180 emails which were utilized to send out the survey questionnaire online. However, only 34 total participant respondents were received back by the researchers, resulting in a 5.3% participation rate.

Characteristics of Participants

The inclusion characteristics of the participants were as follows:

1. Participants must be between the age of 21-60 years

2. Participants must have attended and graduated from a four-year college or university

3. Participants must have taken inclusion or co-teaching courses at the college or university

4. Participants must have taught for a minimum of one year and a maximum of two years

5. Participants must be working in a public school

6. Participants must be teaching in an inclusion classroom

7. Participants may have acquired their teacher certification through alternative or traditional education program

8. Participants must be teaching in a public school located in the geographic region of Iowa State.

Ethical Considerations

This study was conducted with 34 consenting adults who were within the age range of 21-60 years and could make their own legal decisions. Furthermore, the researchers made full disclosure at the top of the questionnaire document sent out through participants’ email addresses. The researchers described the purpose of the study and asked for their voluntary consent. If they agree to participate in the study. Also, participants were informed that they could withdraw from the study at any time without any liability. In addition, participants’ names and personal information were not required in the survey questionnaire, which provided the participants of the study privacy and protection against any form of coercion.

Data Sources and Instrumentation

The choice of using a survey questionnaire as a data collection tool by the researchers was based on the advantage that it was a more straightforward method to use to collect data from many participants of a study (Harrell & Bradley, 2009). Furthermore, a survey questionnaire tool can

2023: Special Education Research, Policy and Practice (SERPP) 13

be used to administer a mix of open-ended and closed-ended questions, which were the format of asking questions that the researchers used to collect data from their respondents. (Harrell & Bradley, 2009). In addition, the use of a survey research questionnaire is a recommended technique in the social science field, mainly if the study includes statistical analysis (Suchman & Jordan, 1990). Based on the rationale that these researchers were using the quantitative research method as a supplemental approach to add value to the dominant qualitative methodology in the study, the use of a survey questionnaire as a standardized data collection procedure was considered appropriate.

Google forms facilitated the mass electronic distribution of invitations to participate, a description of the survey with a statement of purpose, risks, benefits, confidentiality, and a statement of implied consent. The site allowed the researchers to provide personal contact information, a link to the survey, and a source for data collection. All responses to the survey were anonymous. The survey responses were downloaded into a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet and imported into jamovi, a statistical spreadsheet.

The survey for this study was comprised of 18 items. Survey items 1-10 were selected-response questions, and 11-18 were open-ended response questions. Participants responded to questions 13 using a 7-point Likert-type scale. Survey question one asked participants to rate satisfaction with the effectiveness of inclusion courses on current practice. Survey question two asked the participants to rate satisfaction with the skills acquired from the inclusion courses. Survey question three asked the participants to rate satisfaction with the school leadership’s support for the implementation of co-teaching and inclusive practices. Participants responded to question four using a 3-point Likert-type scale. Survey question four asked the participants to rate their knowledge levels of the inclusion principles from student diversity and educational practices and or survey of exceptionalities courses.

Survey items 5-10 asked participants general information questions. Survey questions five, six, and seven asked participants’ highest level of education completed, years of service in a public k-12 classroom, and the type of teacher preparation program attended. Survey questions eight, nine, and ten asked participants to describe their current classroom assignment, and whether the participants were co-teachers, as well as grade levels taught.

Survey question 11 asked participants to describe the inclusion courses taken during the licensure program. Survey question 12 asked participants to describe and explain the effectiveness of the inclusion course in preparing the participant for the classroom. Survey question 13 asked the participants, “what are your current challenges as a teacher working with diverse student populations?” Survey question 14 asked participants what additions and or revisions based on their experiences from current practice do you believe should be made to the student diversity and education practices or survey of exceptionalities courses to make the preservice training relevant to teachers’ field practices.

Survey question 15 asked whether the participant participated in field experience during preservice teaching and, if so, how relevant the experience was to their current practice. Survey question 16 asked participants to describe administrative support in professional development to enhance knowledge of inclusive practices. Survey question 17 asked participants regarding their

2023: Special Education Research, Policy and Practice (SERPP) 14

suggestions for future teachers toward preparation to teach in a diverse classroom. In survey question 18, participants were asked to provide their overall comments.

Data Analysis Approach

The data collected in this study involved the collection of both quantitative and qualitative data as a mixed methods approach. Quantitative data was collected in the form of responses to demographic questions and Likert-scale ranking to assess opinions, attitudes, or behaviors. Additionally, qualitative data were collected through open-ended responses. The qualitative data was collected to identify emerging themes beyond the numeric trends identified in the quantitative data. The focus was on gaining insight into the perspectives of the teachers as they shared their work experiences in inclusion classrooms based on the impact of the inclusion courses they had studied at the university or college. The perspectives of teachers were anticipated to help highlight the effectiveness of university or college inclusion courses regarding the scope and level of preparedness amongst new teachers to further the cause of attaining true diversity and equitable practices in the nation’s school system.

To analyze the quantitative data in this study, descriptive statistics were utilized as the statistical relationship between variables was not examined. The qualitative data in this study were analyzed using thematic analysis of the open-ended responses. The presentation of results from the data will be organized and presented by research question after the presentation of the general information data. The respective data analysis approaches were selected to answer the following research questions:

Quantitative Research Questions

1. How do teachers rate on a scale of 1 -5 the effectiveness of the included courses on their current field practice as inclusion classroom teachers?

2. How do teachers rate the skills they acquired from their inclusion courses on a scale of 15?

3. How do teachers rate the quality of their inclusion courses from the university or college on a scale of 1-5?

4. How do teachers rate school leadership support for co-teachers and the implementation of inclusive practices in their classroom on a scale of 1-5?

5. How do teachers rate their knowledge of the principles of inclusion on a scale of 1-5 based on the skills they acquired from the inclusion class in the university or college?

Qualitative Research Questions

1. How do teachers describe the courses they studied in the university that prepared them to teach in the inclusion classroom?

2. How do teachers describe the specific skills they acquired from the inclusion course they took at the University in terms of preparation to handle students with and without disabilities?

3. How do teachers describe the impact of the University/College inclusion course(s) they studied on their current classroom practice?

4. How do teachers assess the quality and effectiveness of their current practice based on the University/College inclusion coursework they took?

2023: Special Education Research, Policy and Practice (SERPP) 15

5. Do teachers feel their university education inclusion course adequately prepared them to assume the role of an inclusion teacher?

6. What changes do teachers believe are needed in University/College curriculum and instruction inclusion courses?

7. What do teachers believe should be included in teachers’ university education to prepare new teachers for the inclusion classroom?

Descriptive statistics, including frequencies and percentages, were computed for selected response survey items 1-4 and general information items 5-10. Selected response survey items 1-4 involved the use of the Likert scale ranking in which participants were asked questions corresponding to quantitative research questions 1-5. Descriptive statistics were also used for the presentation of the quantitative question 15, which also involved the use of the Likert scale ranking.

To answer the qualitative research questions in this study, the data was collected through openended survey questions. A content analysis approach was utilized to identify themes from the qualitative data. Content analysis involves the identification of patterns within text data to identify themes and concepts from within the data (Krippendorff, 2018; Stemler, 2015). Given the limited sample size and open-ended content available within the data collected from openended survey questions, the use of content analysis was determined to be appropriate for the qualitative data.

Results

One-hundred eighty surveys were distributed to first-and second-year K-12 Iowa public school teachers. A total of 34 of the teachers responded to and completed the survey (5.3%).

General Information Data

The general information collected from the survey respondents included participants’ years of service in a public K-12 classroom, whether or not the participants were co-teachers, highest degree earned, and the type of teacher preparation program attended. Thirty-four teachers responded to these questions. The responses to the general information questions presented to participants are presented in Table 1.

Table 1

Years Teaching, Co-Teacher, Degree Completed, Type of Teacher Preparation Program

2023: Special Education Research, Policy and Practice (SERPP) 16

Characteristic Frequency (n) Percentage (%) Years teaching 1 year 17 50.0 2 years 17 50.0 Co-teacher No 29 85.3 Yes 5 14.7 Highest Degree Earned Bachelor’s degree 27 79.4 Master’s degree 4 11.8

Teachers (N = 34) were asked how many years they had been teaching full-time. Seventeen (50%) were in their first year of teaching, and 17 (50%) were teaching in their second year. Twenty-nine (85.3%) respondents were not co-teachers, and five (14.7%) were co-teachers. Thirteen (38.2%) of the teachers attended an alternative type of teacher preparation program, two (5.9%) attended a master’s initial licensure program, and 19 (55.9%) attended a traditional undergraduate teacher preparation program.

Further general information collected from the survey respondents included current classroom assignments and grade levels taught. Thirty-four teachers responded to these questions. This information is presented in Table 2.

Table 2

Current Classroom Assignments and Grade Levels

Twelve (35.3%) teachers were assigned to a general education classroom; 16 (47.1%) teachers were assigned to a general education inclusion classroom teaching students with and without disabilities, whereas six (17.6%) teachers were assigned to a special education classroom. Teachers were asked to indicate the grade levels taught. Thirty-four respondents revealed fivegrade level ranges, as presented in Table 2. Twelve (35.3%) teachers taught 6-8 th grades.

Quantitative Results

The responses to the quantitative were examined using descriptive statistics. The results of the data analysis and description by research question are included below.

How do teachers rate on a scale of 1 -5 the effectiveness of the inclusion courses on their current field practice as inclusion classroom teachers?

In survey question one, participants were asked to rate satisfaction with the effectiveness of inclusion courses on current practice. The participant responses are included in Table 3. As reflected within the table, the greatest frequency of participants expressed they were satisfied

2023: Special Education Research, Policy and Practice (SERPP) 17

Doctorate 3 8.8 Type of Teacher Prep Program Alternative 13 38.2 Master’s initial licensure 2 5.9 Traditional undergraduate 19 55.9

Characteristic Frequency (n) Percentage (%) Classroom assignment General education 12 35.3 General education inclusion 16 47.1 Special education 6 17.6 Grade levels Pre K-5th 9 26.5 6-8th 12 35.3 9-12th 9 26.5 K-8th 1 2.7 6-12th 3 9.0

(n=13, 38.2%) with the effectiveness of inclusion courses on their current field practice as inclusion classroom teachers. A total of six participants (17.6%) expressed they were completely dissatisfied, dissatisfied, or somewhat dissatisfied with the effectiveness of the inclusion courses on current practice compared to 23 (67.6%) participants that expressed they were somewhat satisfied, satisfied, or completely satisfied with the inclusion courses on their current field practice as inclusion classroom teachers.

Satisfaction with the Effectiveness of Inclusion Courses on Current Practice

How do teachers rate the skills they acquired from their inclusion courses on a scale of 1-5? In survey question two, participants were asked to rate satisfaction with the skills acquired from the inclusion courses. The participant responses are included in Table 4. The greatest frequency of participants expressed they were satisfied ( n=9, 26.5%) with the effectiveness of inclusion courses on their current field practice as inclusion classroom teachers. A total of five participants (14.7%) expressed they were completely dissatisfied, dissatisfied, or somewhat dissatisfied with the effectiveness of the inclusion courses on current practice compared to 22 (64.7%) participants that expressed they were somewhat satisfied, satisfied, or completely satisfied inclusion courses on their current field practice as inclusion classroom teachers.

Satisfaction with the Skills Acquired from Inclusion Courses (n=34)

How do teachers rate the quality of their inclusion courses from the university or college on a scale of 1-5?

Survey question 15 asked whether or not the participant participated in field experience during preservice teaching and if so, how relevant the experience was to their current practice. Seven of the 34 participants expressed that they did not participate in an inclusion course from their 2023: Special Education Research, Policy and Practice (SERPP) 18

Table 3

Response Frequency (n) Percentage (%) Completely dissatisfied 1 2.9 Dissatisfied 1 2.9 Somewhat dissatisfied 4 11.8 Neither dissatisfied nor satisfied 5 14.7 Somewhat satisfied 5 14.7 Satisfied 13 38.2 Completely satisfied 5 14.7

Note. Total number of participants (n) = 34

Table 4

Response Frequency (n) Percentage (%) Completely dissatisfied 1 2.9 Dissatisfied 2 5.9 Somewhat dissatisfied 2 5.9 Neither dissatisfied nor satisfied 7 20.6 Somewhat satisfied 8 23.5 Satisfied 9 26.5 Completely satisfied 5 14.7

university or college and 27 participants expressed that they did participate in an inclusion course. Six of the 27 participants (22.2%) that answered that they participated in an inclusion course within their college or university ranked the program with a 2. The remaining 21 participants (77.8%) ranked the program with a 3. The open-ended responses corresponding to survey question 15 are presented in the presentation of the qualitative data (see Table 7).

How do teachers rate school leadership support for co-teachers and the implementation of inclusive practices in their classroom on a scale of 1-5?

Survey question three asked the participants to rate satisfaction with the school leadership’s support for the implementation of co-teaching and inclusive practices. The results of the responses to survey question three are presented in Table 5. The greatest frequency of participants expressed they were completely satisfied ( n=8, 23.5%) with the school leadership’s support for the implementation of co-teaching and inclusive practices. A total of ten participants (29.4%) expressed they were completely dissatisfied, dissatisfied, or somewhat dissatisfied with the effectiveness of the inclusion courses on current practice compared to 20 (58.8%) participants that expressed they were somewhat satisfied, satisfied, or completely satisfied inclusion with the courses on their current field practice as inclusion classroom teachers.

Table 5

Satisfaction with School Leadership Support for the Implementation of Co-teaching and Inclusive Practices (n=34)

How do teachers rate their knowledge of the principles of inclusion on a scale of 1-5 based on the skills they acquired from the inclusion class in the university or college?

Survey question four asked the participants to rate their knowledge levels of the inclusion principles from student diversity and educational practices and or survey of exceptionalities courses. As reflected in Table 6, the majority of participants (n=26, 76.5%) responded that they were somewhat knowledgeable of the principles of inclusion based on the skills they acquired from the inclusion class in the university or college. One participant responded that they were not knowledgeable (2.9%), and seven participants responded that they had advanced knowledge of the principles of inclusion (20.6%).

Table 6

Knowledge Levels of Inclusion Principles from Educational Practices and or Courses (n=34)

2023: Special Education Research, Policy and Practice (SERPP) 19

Response Frequency (n) Percentage (%) Completely dissatisfied 3 8.8 Dissatisfied 3 8.8 Somewhat dissatisfied 4 11.8 Neither dissatisfied nor satisfied 4 11.8 Somewhat satisfied 5 14.7 Satisfied 7 20.6 Completely satisfied 8 23.5

Response Frequency (n) Percentage (%) Not knowledgeable 1 2.9 Somewhat knowledgeable 26 76.5 Advanced knowledge 7 20.6

Qualitative Results

The responses to the qualitative research questions are presented by the research question. The point at which data saturation was determined to be met for each theme identification was at 7 of the 34 participants (20.6%).

How do teachers describe the courses they studied in the university that prepared them to teach in the inclusion classroom?

In survey question 11, participants were asked to describe the inclusion courses taken during the licensure program. From the responses to survey question 11, as reflected in Table 7, three themes were identified: (a) the inclusion course was introductory and provided basic knowledge, (b) the inclusion course was a positive and beneficial experience, and (c) there was a need for additional resources beyond the inclusion course for practical application in the classroom.

Table 7

Data Themes: How do teachers describe the courses they studied in the university that prepared them to teach in the inclusion classroom?

Data themes Number of Illustrative quotes Participants

The 7 Introductory, becoming aware that students from various inclusion backgrounds will have different social expectations. course was introductory Covered the basics and provided a Adequate basic knowledge

It gave me a basic knowledge of student diversity and different types of students I could work with but nothing beyond that basic knowledge

The 15 Very informative! I learned a lot […] inclusion course was

Great course that provided a variety of general knowledge which a positive helped me have resources for all the different types of classes I and teach and students I have. beneficial experience

Beneficial in helping me gain the knowledge that I needed to know how to best serve my students and to support them in the general education classroom so that they can be included and can participate.

I thought that it was great and a great way to start the program. Need for 9 There was one course that covered special education and that was additional it. resources beyond the

Very general and situational. Nothing working towards helping inclusion us in the classroom. course for 2023: Special Education Research, Policy and Practice (SERPP) 20

practical I recall reading about the many ways that students differ from application each other. Exactly how to utilize that information I don’t recall in the learning. I have had to figure it out as I taught. The intellectual classroom and emotional abilities of the students varied each semester. Just when I think I have it figured out, a new situation arises.

It taught a lot about how to not be racist which is perfectly valid and necessary to teach. However, I do not recall being taught any tools for growing students understanding of diversity and how to promote proper inclusion in a classroom.

How do teachers describe the specific skills they acquired from the inclusion course they took at the University in terms of preparation to handle students with and without disabilities?

Survey question 15 asked participants whether or not they participated in field experience during preservice teaching and if so, how relevant was the experience to their current practice. In the open-ended response, four of 34 participants did not respond. Of the 30 participants that did respond, 19 participants (63.3%) expanded their response to state that the program was relevant and helpful in providing practical experience. Additional details regarding how the program was relevant were limited. Eight participants (26.7%) expressed that the field experiences had limited relevance or that the effectiveness of the field experience could have been improved.

How do teachers describe the impact of the University/College inclusion course(s) they studied on their current classroom practice?

Survey question 14 asked participants, “what additions and or revisions based on your experiences from current practice do you believe should be made to the student diversity and education practices or survey of exceptionalities courses to make the pre-service training relevant to teachers’ field practices?”. Eight of 34 participants did not respond to survey question 14. Due to the reduced number of participant responses, data saturation for each theme was set at 6 participants (23.1%). From the 26 responses that were received, the following themes were identified, as reflected in Table 8: (a) no changes are needed, and (b) a need for more practical skills and practice that can be implemented in the classroom.

Table 8

Data Themes: How do teachers describe the impact of the University/College inclusion course(s) they studied on their current classroom practice?

Data themes

Number of

Illustrative Quotes Participants

No changes are 6 None! Just treat everybody by the content of their character needed and not their skin color.

I think it should stay the same.

I can’t think of any at the moment.

More practical 14 Talk and learn from other teachers’ experiences. skills and 2023: Special Education Research, Policy and Practice (SERPP) 21

practice can be Focus on techniques instead of the facts implemented in the classroom

I think we need to practice having conversations and talking about it as staff not just be passive listeners in training but active participants. Like role play

More real-life scenarios to practice accommodating all students.

Give practical ways to adapt your lessons that are easy to implement for any type of lesson

How do teachers assess the quality and effectiveness of their current practice based on the University/College inclusion coursework they took?

Survey question 16 asked participants to describe administrative support in professional development to enhance their knowledge of inclusive practices. Eight of 34 participants responded N/A or did not respond to the question. Of the remaining 26 participants that responded to the question, 15 participants (57.7) expressed that the administrative supports were available, helpful, and receptive to new opportunities and involvement. Nine participants (34.6%) expressed a specific lack of support and/or a lack of attention to inclusion practices within with school in which they work.

Do teachers feel their university education inclusion course adequately prepared them to assume the role of an inclusion teacher?

Survey question 12 asked participants to describe and explain the effectiveness of the inclusion course in preparing them for the classroom. As reflected in Table 9, two themes were identified from the open-ended responses of study participants: (a) the inclusion course was very effective in preparing participants for the classroom, and (b) the inclusion course was somewhat ineffective as there was a need for additional education on how to address real situations in the classroom.

Table 9

Data Themes: Do teachers feel their university education inclusion course adequately prepared them to assume the role of an inclusion teacher?

Data themes Number of Illustrative quotes Participants

The inclusion

12

Incredibly effective. I feel aware of student needs and prepared course was to differentiate in a variety of ways. very effective

Very effective, I feel very well prepared at my job for anything that comes up, and if I did need help, I have and know resources to reach out to.

2023: Special Education Research, Policy and Practice (SERPP) 22

It was effective because it helped me gain a better understanding of all types of students and how to best support them.

It prepared me for things I never thought I would have to work with, and it prepared me on how to handle these situations.

I think it was great because it gave me the perspective of many unique students and how their classroom experiences help them get to where they are today.

The inclusion 17 It was decent but I think it would be nice to see instructors who course was have implemented real changes in their classrooms and hear somewhat them reflect on that. ineffective as They give me good ideas to use in my classroom for there was a exceptional learners, but you won’t know how to accommodate need for for a student until you have met them and worked with them. additional education on

Somewhat effective. I have the knowledge of why this is how to address important, but I want more resources and practical experience real situations in the

Considering there were not many courses I would say the classroom effectiveness was low.

Like so many areas covered in the Alternative program, it is one thing to read about it, another to live it.

What changes do teachers believe are needed in University/College curriculum and instruction inclusion courses?

Survey question 13 asked the participants about their current challenges as a teacher working with diverse student populations. Three of the 34 participants did not respond to survey question 13. As reflected in Table 10, from participants’ open-ended responses, two themes were identified: (a) addressing the simultaneous needs of a diverse student population and (b) teaching content at different levels to meet differing academic needs. Within the first theme that was identified, the issue of language barriers and problem behaviors were identified as two subthemes.

Table 10

Data Themes: What changes do teachers believe are needed in University/College curriculum and instruction inclusion courses?

Data themes Number of Illustrative quotes

Data subthemes Participants

Addressing the 19 Getting them to work with students from different simultaneous backgrounds. needs of a 2023: Special Education Research, Policy and Practice (SERPP) 23

diverse student

Finding a way to differentiate for all and finding the time to population work with students who need extra help.

How to effectively accommodate for all needs in my room to meet each student where they are for the maximum learning.

The language barrier for sure language barriers among

Being an ESL teacher, my biggest challenge is understanding ELL students my students and their experiences. […]

Severe behaviors and how to support them. Social skills as how to support well. students with problem

Having the necessary time to develop relationships with all of behaviors the students due to huge class sizes and teachers having to deal with large amounts of behaviors related to technology and cell phones.

Teaching 7 Meeting everyone’s needs without letting those who are content at average get forgotten about. Sometimes you feel like you are different levels catering to certain students much more and not to others. to meet

differing

Teaching material on different levels academic needs

Learning how to best serve the students in their specific areas and how to help them make the most growth in their academic areas.

Assessing ability; is this student exhibiting learned helplessness or are they working at their top level.

Finding ways to make things possible for all students at once without me having to spend a bunch of extra time prepping things. Especially at the kindergarten level where all students, no matter their differences, need help with the basics

What do teachers believe should be included in teachers’ university education to prepare new teachers for the inclusion classroom ?

In survey question 17, participants were asked to provide suggestions for future teachers toward preparation to teach in a diverse classroom. One participant out of 34 did not respond to survey question 17. Two themes were identified in response to survey question 17 and are presented in Table 11.

Table 11

Data Themes: What do teachers believe should be included in teachers’ university education to prepare new teachers for the inclusion classroom?

2023: Special Education Research, Policy and Practice (SERPP) 24

Data themes Number of Illustrative Quotes Participants

Utilize the 8 Again, have an opportunity to lessen other teachers’ experiences of successes and failures. other teachers and support of Try to get experience watching others and have an open administrative mind staff as resources

Find people to use as resources and keep up to date

Take great notes and observations during student teaching. Reach out to your cooperating teachers, admin, or colleagues for support.

Perhaps a workshop to discuss with teachers what they encounter and how to handle it. Identify the focus and discuss concrete strategies.

Be prepared to be 10 it takes time to figure out how your classroom will work flexible and open best and how to develop a relationship with your students to learning that allows both sides to succeed.

through practice

Be prepared to have students at every level. Be careful how you talk to and about students because it makes a big impact.

Go into it open-minded and remember to always ask questions to gain a better understanding of the students or population that is in the school and how to best serve them.

Learn from experience.

As awkward and uncomfortable as it might make you feel to go into a classroom for the first time in a long time, it’s very helpful and gets you important exposure to the profession.

Discussion

In evaluating the effectiveness of university/college teacher preparation inclusion courses from the perspectives of beginning K-12 special education and general education teachers prepared in traditional and alternative teacher education programs, the quantitative results yielded in this study demonstrate that among each measured factor, the majority of participants were satisfied with their preparation program. Similarly, within the qualitative results, participants expressed their satisfaction with the knowledge obtained within their preparation programs, noting that the program helped them to consider how to best support students within a diverse classroom.

2023: Special Education Research, Policy and Practice (SERPP) 25

Despite the articulation of general satisfaction with preparation programs for diversity, inclusion, and equity, challenges and gaps within the programs were expressed. Participants noted a gap between knowledge and practice. Namely, the challenge remains in how to apply the lessons learned within preparation programs to support a diverse and sometimes challenging student population within the context of the classroom. Recommendations for integrating additional realworld examples and hands-on practice as part of training programs were recommended to improve teachers’ success in ensuring equity and inclusion within a diverse classroom. These should include school districts adopting and using hermeneutic approach in the professional development of teachers in their first two years of teaching assignment; by consistently reevaluating teachers’ practical skill’s development in the classroom and using veteran teachers as coaches and mentors to monitor their career trajectory in developing inclusion skills. In addition, school districts should consider using veteran teachers with double credentials in special and general education who have vast experience working with students’ population of diverse background, to help new teachers nurture their practical skills and real life applications.

Limitations and Future Research

The major issue anticipated is in consideration of the COVID situation in the nation today, this research study focused on administering interview questionnaires as a data collection method. Normally in qualitative research that deals with a face-to-face contact interview with human beings, the researcher can make immediate clarifications while talking to the participants and through observing their body language and facial expressions, can make deeper meaning from their responses. Secondly, the sampled participants were limited to the specific geographic region of Iowa State and therefore, limits research generalization. The research findings should be limited and analyzed only within the context of the geographic region of Iowa where the study was conducted.

Conclusion

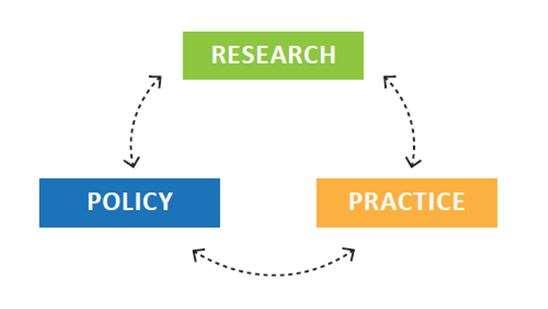

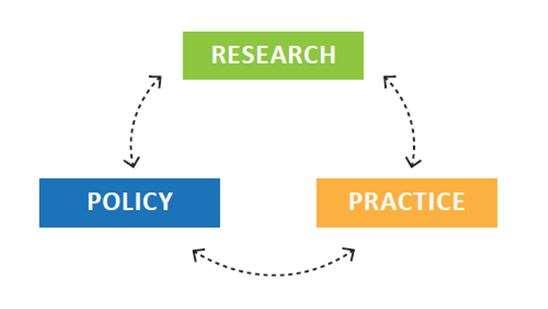

The findings of this study are relevant for both research and practice. First, the study contributes to the existing literature on diversity, inclusion, and equity, as well as the challenges faced in advancing inclusive education. Additionally, the research presents specific areas to address in practice. Integrating additional real-world examples and hands-on practice as part of training programs was recommended to improve teachers’ success in ensuring equity and inclusion within a diverse classroom is a key recommendation from this study. For policymakers, the inclusion of real-world experience should be a priority in improving educators’ experience and capacity to address inclusion and equity in practice.

References

Arnesen, A. L., & Allan, J. (2009). Policies and Practices for teaching socio-cultural diversity: Concepts, principles, and challenges in teacher education. Council of Europe Publishing , CHP One, 10-16. ISBN 978-92-871-6440-7.

Allday, R. A., Neilsen-Gatti, S. & Hudson, T. M. (2013). Preparation for inclusion in teacher education pre-service curricula. Teacher Education and Special Education, 36 (4), 298311.

2023: Special Education Research, Policy and Practice (SERPP) 26

Banks, J.A. (2004). Multicultural education: Historical development, dimensions, and practice. In J.A. Banks, & C.A.M. Banks (Eds.), Handbook of Research on Multicultural Education (2nd ed., pp. 3-29). Jossey-Bass.

Banks, J.A. (2001). Cultural diversity and education: Foundations, curriculum, and teaching. Allyn & Bacon.

Bell, L. A. (2002). Sincere Fictions: The pedagogical challenges of preparing white teachers for multicultural classrooms. Equity and Experience in Education, 35 (3), 236-244

Burns, T., & Shadoian-Gersing, V. (2010). The importance of effective teacher Education for diversity. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264079731-43n

Brownell, M. T., Ross, D. D., Colon, E. P., & McCallum, C. L. (2005). Critical features of special education teacher preparation: A comparison with general teacher education. The Journal of Special Education, 38 (4), 242-252.

Biernacki, P., & Waldorf, D. (1981). Snowball Sampling: Problems and techniques of chain referral sampling. Sociological Methods and Research, 10 , 141-163.

https://doi.org/10.1177/004912418101000205

Caruth, G. D. (2013). Demystifying mixed methods research design: A review of the literature. Meylana International Journal of Education, 3 (2).

Creswell, W. (2014). Research design: Qualitative, Quantitative, Quantitative and Mixed Methods Approaches (4th Ed.). Sage

Darling-Hammond, L., (2010). Teacher education and the American future. Journal of Teacher Education, 61(1-2), 35-47.

Darling-Hammond, L. (2000). Teacher quality and student achievement. Education Policy Archives, 8, 1-1.

Doyle, L. Brady, A. M., Byrne, G. (2009). An overview of mixed methods of Research. Journal of Mixed Methods of Research in Nursing, 14 (2), 175-185

Florian, L. & Camedda, D. (2020). Enhancing teacher education for inclusion. European Journal of Teacher Education, 43 (1), 4-8.

Forlin, C. (2010). Reframing teacher education for inclusion . Teacher Education for Inclusion. Gay, G. (2015). The what, why, and how of culturally responsive teaching: International mandates, challenges, and opportunities. Multicultural education review , 7(3), 123-139.

Gay, G. (2010). Culturally responsive teaching: Theory, research, and practice Teachers College Press.

Gill, P., Sherman, R., & Sherman, C. (2009). The impact of initial field experience on preservice teachers’ attitude toward inclusion. Educational Leadership and Policy Studies Faculty Publications and Presentations . Paper 19.

Goldenberg, B. M. (2014). White teachers in urban classrooms: Embracing non-white students’ cultural capital for better teaching and learning. Urban Education, 49 (1), 111-144

Graham, L. J., & Harwood, V. (2011). Developing capabilities for social inclusion: Engaging diversity through inclusive school communities. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 15(1), 135-152.

Grant, C. & Gibson, M. (2011). Diversity and teacher education. Studying Diversity in Teacher Education, 19-62.

https://www.academia.edu/529047/Diversity_and_teacher_education_A_historical_persp ective_on_research_andpolicy_chapter1

Gregory, J. (2018). Not my responsibility: The impact of separate special education systems on educator’s attitudes towards inclusion. Educational Policy Analysis and Strategic Research, 13(1), 127-148.

2023: Special Education Research, Policy and Practice (SERPP) 27

Haddix, M. (2008). Beyond sociolinguistics: Towards a critical approach to cultural and linguistic diversity in teacher education. Language and Education, 22 (5), 254-270.

Hancock, B., Ockleford, E., & Windridge, K. (2007). An Introduction to Qualitative Research. Beverly Hancock.

Handcock, M. S., & Gile, K. J. (2011). Comment: On the concept of snowball sampling. Sociological methodology , 41(1), 367-371.

Harrell, M. C. & Bradley. A. M. (2009). Data collection methods: Semi-structured interviews and focus groups. National Defense Institute.

https://www.rand.org/pubs/technical_report/TR718.html

Hatton, N. & Smith, D. (1995). Reflection in teacher education: Towards definition and and implementation. Teaching and Teacher Education, 11 (1), 33-49

Hoppey, D. (2016). Developing educators for inclusive classrooms through rural schooluniversity. Partnership Rural Special Education Quarterly, 35 (1), 13-22.

Imig, D., Wiserman, D., & Imig, S. (2011). Teacher education in United States of America. Journal of Education for Teaching. International Research and Pedagogy, 37 (4), 399408.

Jelas, Z. M. (2010). Learner diversity and inclusive education: A new paradigm for teacher education in Malaysia. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 7 , 201-204.

Krippendorff, K. (2018). Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology Sage Publications.

Kumar, R., Zusho, A., & Bondie, R. (2018). Weaving cultural relevance and achievement motivation into inclusive classroom cultures. Educational Psychologist , 53(2), 78-96.

Lancaster, J., & Bain, A. (2019). Designing university courses to improve preservice teachers’ pedagogical content knowledge of evidence-based inclusive practice. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 44 (2), 51-65.

Liggett, T., & Finley, S. (2009). Upsetting the apple cart: Issues of diversity in preservice teacher education. Multicultural Education, 16 (4), 33-38.

Lindner, K. T., Alnahdi, G. H., Wahl, S., & Schwab, S. (2019, July). Perceived differentiation and personalization teaching approaches in inclusive classrooms: perspectives of students and teachers. In Frontiers in Education (Vol. 4, p. 58). Frontiers Media SA.

Loewenberg, B. D., & Forzani, F. M. (2009). The work of teaching and the challenge for teacher education. Journal of Teacher Education, 60 (5), 497-511

Logan, B. E., & Wimer, G. (2013). Tracing inclusion: Determining teacher attitudes. Research in Higher Educational Journal, 20 , 1-10.

Martin, R. J. (1994). Multicultural social reconstructionist education: Design for diversity in teacher education. Teacher Education Quarterly, 21 (3), 77-89.

McCray, E. D., & McHatton, P. A. (2011). Less afraid to have them in my classroom: Understanding pre-service general educators’ perceptions about inclusion. Teacher Education Quarterly, 38 (4), 135-155

McFalls, E.L. & Cobb-Roberts, D. (2001). Reducing resistance to diversity through cognitive dissonance instruction: Implications for teacher education. Journal of Teacher Education, 52(2),164-172.

Milner IV, H.R. (2010). What does teacher education have to do with teaching? Implications for diversity studies. Journal of Teacher Education, 61 (1-2), 118-131.

Morina, A., Cortes-Vega, M. D. & Molina, V. M. (2015). Faculty training: An unavoidable requirement for approaching more inclusive university classrooms. Teaching in Higher Education, 20(8), 795-806.

2023: Special Education Research, Policy and Practice (SERPP) 28

Naderifar, M., Goli, H., & Ghaljaie, F. (2017). Snowball Sampling: A purposeful method of sampling in qualitative research. Strides in Development of Medical Education, 14 (3), 1-6. https://doi.org/5812/sdme.67670

National Center for Education Statistics. (n.d.) nces.ed.gov/program/coe/indicator/cgg

Peebles, J., & Mendaglio, S. (2014). Preparing teachers for inclusive classrooms: Introducing the individual direct experience approach. Learning Landscapes, 7 (2), 245-257.

Peterson-Ahmad, M.B., Hovey, K.A. & Peak, P.K. (2018). Pre-service teacher Perceptions and knowledge regarding professional development: Implications for teacher preparation programs. Journal of Special Education Apprenticeship, 7(2), p. 1-17.

Plash, S. H., & Piotrowski, C. (2006). Retention issues: A study of Alabama special education teachers (Doctoral dissertation, University of West Florida).

Prasetyo, T., Rachmadtullah, R., Samsudin, A., & Aliyyah, R. R. (2021). General Teachers' Experience of the Brain's Natural Learning Systems-Based Instructional Approach in Inclusive Classroom. International Journal of Instruction , 14(3), 95-116.

Roose, I., Vantieghem, W., Vanderlinde, R., & Van Avermaet, P. (2019). Beliefs as filters for comparing inclusive classroom situations. Connecting teachers’ beliefs about teaching diverse learners to their noticing of inclusive classroom characteristics in videoclips. Contemporary Educational Psychology , 56, 140-151.

Russell, T., McPherson, S., & Martin, A.K. (2001). Coherence and collaboration in teacher education reform. Canadian Journal of Education/Revue Canadienne de l’education , 3755.

Shorten, A. & Smith, J. (2017). Mixed methods research: Expanding the evidence base. Evidence-based nursing, 20(3), 74-75

Siuty, M. B. (2019). Teacher preparation as interruption or disruption? Understanding identity (re) constitution for critical inclusion. Teaching Teacher Education, 81 (1), 38-49.