How to Raise a Money-Wise Child

How to Raise a Money-Wise Child

Paperback

ISBN: 978-962-746620-8

Text and illustrations © 2006

The Hong Kong Institute of Certified Public Accountants

www.hkicpa.org.hk

Second edition 2011

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a review.

Text by Howard Tang

Illustrations by Jeffrey YehDear parents,

We are delighted to share with you this book on helping your children become financially responsible.

We have written the book with busy parents in mind, so that you can read a quick tip when you have a minute. We hope it will give you ideas you can put to use and some food for thought.

At the Hong Kong Institute of CPAs, we promise we are the “success ingredient” in the businesses we serve and the communities in which we live. We thought this book would be useful for Hong Kong parents who work hard and want the best for their children.

Much of the information came from our members, who by all means do not agree on how best to teach their children financial management skills, but do agree that it is important.

If you like the book, please e-mail us at hkicpa@hkicpa.org.hk.

Sincere regards,

The Hong Kong Institute of CPAsIntroduction

The Hong Kong Institute of Certified Public Accountants believes that, as accountants and experts in financial management, it has something to contribute to the topic of raising financially responsible children. After all, who is more qualified to teach financial responsibility than the people who do it for a living?

This book addresses teaching children between the ages of three to 12 and focuses on financial responsibility, not entrepreneurship, for three reasons:

Concepts of financial responsibility are complicated; these concepts also take discipline for parents to teach.

Financial responsibility is different from financial ability

For parents who want to shield their children from the pressures of the real world for as long as possible, it's better to teach handling and managing money rather than making it.

We also recognise that one thing Hong Kong parents are short of is time. That's why this book is designed as a guidebook, presenting the main points in an easy-to-read and concise manner.

The content of this book is developed from the expertise of the Hong Kong Institute of CPAs and members who are parents as well. It is also the beneficiary of information and insight from a variety of sources such as the children of accountants, social workers, teachers and young professionals.

We have talked to many parents whose insights we have quoted throughout this book without directly naming them. We would especially like to thank the Accountant Ambassadors of the Hong Kong Institute of CPAs. Their time and effort in sharing stories with the author added greatly to the richness of its content.

On the note of "richness," let us begin.

Age 3-5

In this age group, children have begun pre-school or nursery and are on their way to kindergarten. They are able to recognise numbers and the alphabet, and it’s time to start learning about the root of financial responsibility: cash

Cash is king

This is where it all starts. Cash is the basis of all budgeting and financial responsibility. Not only that, to accountants and business people, the cash flow statement is all important. In fact, of the three financial statements (cash flow, income and balance sheet) examined by accountants, cash flow is the first one accountants study in training and emphasise and use in practice.

Think about it: How could any business operate without cash for rent, employee salaries, advertising, legal advice, product development, photocopies, long distance calls and all other business expenses? It’s the same for families: families need money for rent and other expenses of daily life.

To teach your children how to responsibly manage money from an early age is to teach them an indispensable life skill.

And for little children, financial responsibility can start with a thorough understanding of cash.

How cash came from bartering

Once people figured out that exchanging things amongst themselves made life easier and gave them better lives, they developed a bartering system. If you didn’t have a goat but you needed one, you traded something you owned, like two chickens, for the goat.

Two chickens for one goat may have seemed like a fair trade but it’s easy to see how the system got too complicated. What happens when you only have two chickens but you need a cow? How about a quarter of a cow for the two chickens? In that case, does that mean the cow has to be killed, or at the very least maimed? Is a dead or disabled cow still worth as much?

As the difficulties and idiosyncrasies of a bartering system began to surface, cash emerged. For a bartering system to work, buyers and sellers needed and developed a way to determine worth and price:

Precious metals such as gold, silver, and copper were used as currency in Egypt and Asia Minor as early as 2500 B.C., historians hypothesise. Coins were developed as early as 700 B.C. and facilitated payment in terms of tale, or counting out the right amount, as opposed to weighing the precious metals.

Some historians trace the origins of paper money back to the reign of Kublai Khan in the 13th century, whose administration used mulberry bark bearing the Khan’s seal and his treasurers’ signatures. They also say paper money in the Ming Dynasty (the late 14th century) was about the same size as a sheet of A4 paper. Paper money didn’t catch on in Europe until centuries

later when Sweden became the first European country to print bank notes in the 17th century.

Recognising cash

Counting games: show your children how 10 one-dollar coins equal one 10-dollar note or coin. Show them how two 10-dollar coins or bills can be a 20-dollar bill, and so on.

Understanding the value of cash

One of the most difficult lessons for parents to teach is that value is relative; for children to fully understand the value of cash, you’ll need to explain it to them in their terms. For example, one dollar equals two pieces of candy or 10 dollars equals a small toy makes sense to a child.

As one Hong Kong parent explains:

“I tried explaining to my son that one dollar equalled 10 10-cent pieces. I think he understood this but he didn’t seem to get the fact that one dollar was not enough to buy a house. He kept trying to buy everything for one dollar because he thought that 10 10-cent coins was a lot of money.”

A common exercise to help very young children start making the proper association between money and what it can buy is to let them hand the cash to supermarket or McDonald’s cashiers. This way, they can concretely see that money, in various amounts, can bring them things they recognise and know. If they hand over $200 for a bag of groceries from PARKnSHOP, they will learn to make the association between cash and groceries.

Lai see

Most parents we talked to say children begin to develop a sense of ownership around the age of five and as early as the age of three. Until that sensibility emerges in your child, lai see money should be under your jurisdiction. As children grow older and learn to recognise the importance and value of cash, lai see becomes a need-to-be-discussed issue.

By the time your children are five, even if they do not appear ready to handle lai see, you might consider at least pretending to pass it into their care because lai see is a great way to start learning about cash.

Moreover, children soon realise that lai see is something special—and meant just for them—thus enhancing their concepts of self and ownership.

One Hong Kong parent explains:

“Before my kids turned three years old, I would hold their lai see for them. But after a while, I think around the age of four or so, they began to take initiative and asked to keep their lai see themselves. When I said to them that I was afraid they would lose or misplace it, they just wouldn’t take ‘no’ for an answer.”

What does handling lai see mean, exactly? Well, for starters, let your children count the money on their own. Doublecheck it for them so that no money goes missing, but it’s important for them to count the money themselves because first, they need to know it belongs to them, and second, they need to know that counting it correctly is an extremely important matter.

For very small children, you might need to count the money with them several times. Once it’s counted, they need to decide, on their own, where to put the money.

Piggy banks

Piggy banks, whether they’re piggy-shaped or not, have served parents and children well for many generations and are indispensable for introducing children to the concept of saving. With a piggy bank, children associate money with saving even before they learn to spend it.

Types of piggy banks

With traditional Chinese clay piggy banks, you have to break them in order to get the money. The idea is that your kids will think twice before breaking the bank to get the money. These banks are now hard to find (last seen available in some small shops on Lantau Island) because westernised piggy banks are much more popular, but any saving method clearly demonstrating the idea of “breaking the bank” will do.

A Hong Kong man explains:

“Growing up, all the kids had traditional clay piggy banks— the only alternatives were glass jars or tin cans, but it was easy to snitch money from these and they didn’t serve to teach saving very well. But when it came to clay banks, the only way to take out money was to either take a hammer to the bank or fish it out with wire.

“This is why I, and a good number of my friends, have bought our kids traditional clay piggy banks even though there are many other choices. If the only way to take out money is to break the bank or to use clothes hangers to dig out the money, hopefully it’ll make my kids think twice before doing so.”

Some parents like to use individual piggy banks for separate purposes: saving, spending, and sharing, to clearly dem-

onstrate the differences amongst the three. Whether it be three of the same piggy banks with different labels or three altogether different piggy banks doesn’t really matter as long as it illustrates the different purposes of money and saving.

Some parents like to use transparent piggy banks for the spending bank because it lets children clearly see progress towards specific purchases—like a toy for themselves or a present for grandma. A transparent piggy bank lets them easily see how far they’ve come and how far they have to go, which is another great savings lesson.

Some parents tend to want to dictate when deciding how much their children save and how much to spend. To truly help children develop a sense of personal financial responsibility, guide them instead of telling them. Even at this early age, when they might make bad decisions, let them decide based on your guidance and advice.

Look at it this way: If they make mistakes now, at least these mistakes are relatively minor and what better lesson is there than their own mistake?

Age 6-9

In this age group, when children have entered lower primary school, they have begun to learn simple arithmetic (addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division) so they are ready to move on and apply their new skill sets.

Practise what you preach

To begin with, it’s best that you practise what you preach and serve as a consistent role model. It’s easier for you to teach principles of financial responsibility if you practise them, but even if you don’t think you’re a good financial manager, you can still teach your children to be better at it than you are.

One Hong Kong mother relates when she realised this:

“I tried to get my daughter to spend less and to not go for the brand name purse but she said to me, ‘But Mom, what about the nice Gucci purse that you use every day.’ Needless to say, I was speechless.”

Statistics prove the value of parental role modelling and the importance of practising what you preach. According to

a study by Caritas Medical Centre and Hong Kong Polytechnic University, children from financially troubled families are more likely to face financial troubles themselves at some time in their lives.

Right attitude

Professional accountants and parents alike agree that instilling the right attitude is more than half the battle in teaching financial responsibility. But what is the right attitude and how can it be developed?

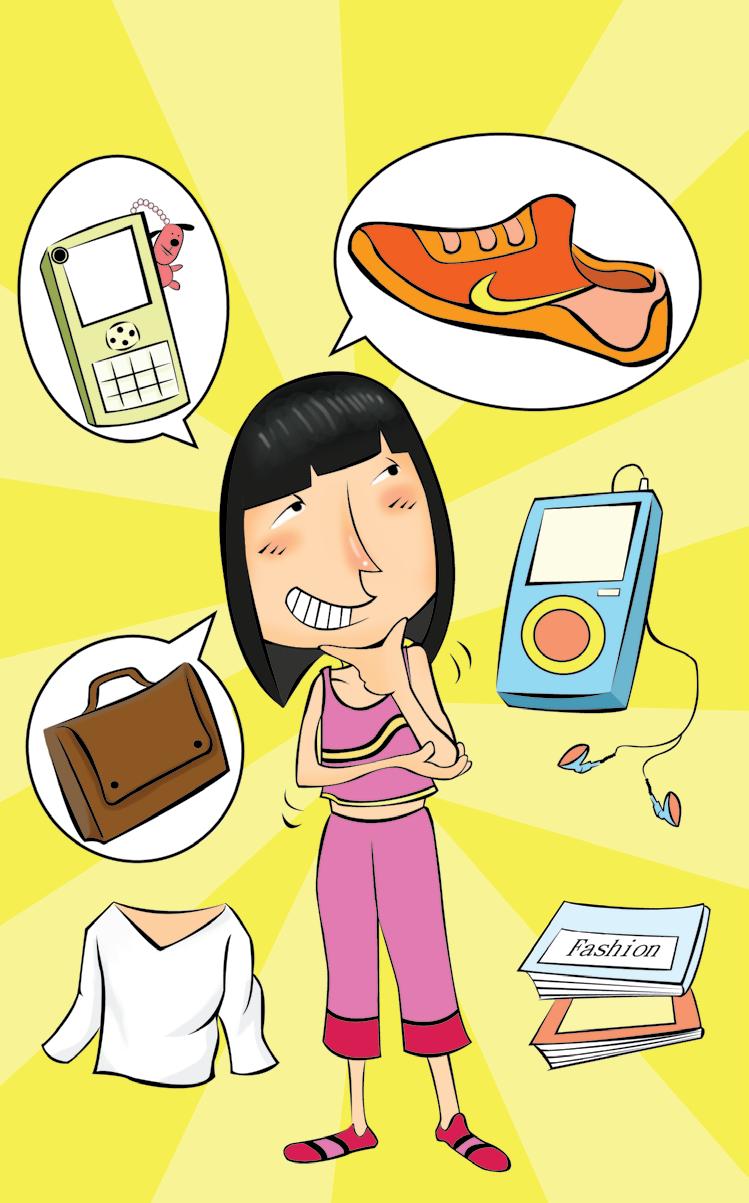

Recognising “want” versus “need” is the first step. Particularly at a young age, your children need to develop this attitude and way of thinking because it will affect them in the future. Until they learn to distinguish between want and need, they will not learn to be financially responsible.

Many children believe that because everyone else has it, it must be a need. Let them know that Nike sneakers are not a need because non-premium-brand sneakers can do the job as well. (You can explain this to them even if all along you planned to buy them the Nike sneakers.)

The concept of want versus need overlaps with practise what you preach. It helps you instill the right attitude if you have it yourself, but even if your attitudes could use some improvement, you can still help your kids.

And who knows? Maybe as you help your children you’ll improve your own skills. You might want to do the want versus need exercise yourself before going through it with your children.

In sophisticated Hong Kong, it makes sense to address brand name issues as early as possible. As such, the previously mentioned Nike versus no-brand discussion could be relevant, even at this age.

Do I want it or do I need it?

Item Want Need

Clothing

Food

Nike sneakers

8 sets of Lego

Prada school bag

Bus

Taxi

Awareness of money is the second step. As Hong Kong is a relatively affluent society, children may not always be aware that money is a serious issue. Let them know that everything costs something, and that money is earned. Bring it up at all possible and relevant times. Imagine planting seeds in their heads. These ideas may not take root or grow until a much later stage, but planting the seeds and fertilising them is a must.

This man explains his view:

“When I was a kid, I never took anything for granted. I had to work for everything—whether it was allowance or tuition. I had to pay for it myself. Kids nowadays are so lucky. This is an important message to hammer into them whenever the opportunity arises because otherwise, they will end up taking it for granted.”

The third step in developing the right attitude is instilling moral values along with money management values. Let them know that virtue can be its own reward.

A parent has this to say:

“I have a hard time striking a balance between teaching the value of money and importance of money. On the one hand, kids need to know that money is very important in that they need to work for it and that it buys livelihood, but on the other hand, they also need to realise that it doesn’t buy happiness. I suppose the lesson here is that kids need to learn that money is a means and not an end.”

The fourth step is to arrange “deals” with them where a sense of personal responsibility can be developed. One parent we talked to used a “if you break it, you buy it” policy:

“My son was quite clumsy. He would always trip over himself or hurt himself while playing. At home, many things have been broken because of his carelessness and lack of coordination.

“Interestingly enough, once we instituted a ‘you-break-ityou-buy-it’ policy around the house, he became a world-class athlete almost overnight. His dexterity improved ten-fold. I think he began to realise that he could no longer afford to be careless or irresponsible.”

Allowance

Most accountants believe that an allowance is a useful tool in teaching financial responsibility. If you are one of those parents who choose not to give your children an allowance, opting instead to give them money whenever they ask for it as a way to control their spending, you should reconsider. Not only does the control result in more work for you, it also results in fewer opportunities for your children to learn financial responsibility.

Giving them an allowance but also giving them money when they ask for it does not fulfill the definition of an allowance. In fact, supplements to an allowance defeat the purpose of an allowance—to teach them budgeting.

These parents explain how difficult it is to get the balance right:

“I never got an allowance. From primary school all the way through university I just asked for money whenever I needed it. It wasn’t until I started working that I began to realise that I had very limited budgeting skills.”

Some children shun an allowance either because they feel they don’t need one or because they see it as troublesome. If your child happens to be one of these rare breeds, insist on giving an allowance anyway because as training, it’s crucial.

“I don’t know if my children are angels or just lazy, but every time I bring up the idea of an allowance they seem to have no interest at all.”

You may be one of those parents who do not give an allowance, opting instead to make your kids earn their own money so they learn to work.

Teaching this necessity is critical and worthy—however, it’s important to distinguish between an allowance and cultivating a right attitude towards money. If working is their only means of getting money, they may equate money with freedom instead of its real value as a tool for surviving and living. Equating money with freedom could lead to big problems as your children grow older. A parent recalls his experience:

“Making money and finding summer jobs became priorities for me because it was the only way I could do whatever I wanted to do. I hated the feeling of having to ask for money every time I wanted to go out with friends. Now that I look back, I probably could’ve used more time just being a kid.”

Determining the dollar figure for an allowance depends on your family situation. According to parenting experts, too much allowance doesn’t give children the chance to learn about budgeting and too little may make your children hoarders and won’t teach them budgeting either. An appropriate allowance most likely reflects your children’s peers (think of it as the “market average”).

As mentioned, an allowance provides a way for your children to make and learn from their own mistakes—if they decide to blow all their allowance on something useless or compulsive, let them. If they save up and pay for something that they end up not liking or needing or wanting, that’s a good lesson.

This man says it was a tough lesson:

“I learned about impulse buying and overspending the hard way, in other words, through many mistakes. I would blow a whole month’s allowance on one night out with friends—dinner, movie, drinks—doing the grown-up thing, and then spend the rest of the month sitting at home. Or I would buy something like a pair of the newest and trendiest sneakers, wear them a couple of times, and then realise that I didn’t really like them after all.

“There is no return policy here and there certainly was no eBay back then, so I was pretty much stuck with something that I didn’t really need or like, but had paid good money for.”

An allowance increase based on age is fair and appropriate because as children grow older, their needs and wants grow (more expensive) too.

Many parents withhold allowance as a form of punishment. The benefit of this method is that it is direct and obvious, but the drawback is that your children may psychologically associate misbehaviour with money.

For example, if breaking a curfew costs 50 dollars, as long as your child has the money, they may decide that it is okay to break curfew—not realising curfew is meant to develop personal discipline and keep parents from waiting up and worrying about their children. A parent tells how her system needed adjusting:

“I had a fine system set up where my son would lose part of his allowance for mistakes that he made. So, for example, he would be fined $100 for not keeping his room tidy. One day, he just decided that not having to put in the time and effort to clean

up his room was worth more than the $100 fine so he figured he might as well not clean his room.

“He definitely did not learn the value of keeping his room tidy and the system certainly did not work. I think grounding him, or, some other form of non-monetary punishment, would have worked better.”

Opening a bank account at “Bank of Parents”

Many parents in the accounting profession suggest opening a beginner’s bank account, the “Bank of Parents.” This is the sequel to piggy banks because a real bank account may not be realistic at this point, but establishing a viable alternative is an essential next step to learning financial responsibility.

Moving on from piggy banks will also give your kids the idea that they have matured and are more responsible and sophisticated.

Opening an account at “Bank of Parents” means buying a notebook for them and teaching them basic bookkeeping. Explain to them that credit means an addition to the account while debit means a subtraction from the account. The result of these various in and out transactions is reflected in the balance.

Make sure your children keep and update their own savings books because it’s important that they know it’s their responsibility. Check for mistakes and verify their math, but make sure that they develop a sense of ownership.

This simple bookkeeping format is easy to draw into any plain or lined notebook and can help your child learn to keep financial score:

Incentive to save

Now that we have set up a “Bank of Parents” account for your kids and started them off with the basics of bookkeeping, it’s time to do what any real bank would do—offer a savings interest rate.

Similar to the way banks entice people by offering an incentive in the form of interest, “Bank of Parents” (i.e., you) could lure your children to leave their money with the bank by offering interest.

Once your children have mastered basic arithmetic (for the most part, lower primary school students should have done so), they should be able to learn about savings and interest rates.

The fact that money and time can lead to more money should be more than enough incentive for them to want to save.

Teach them to calculate interest rates and the differences between simple and compound interest.

Simple interest

Five percent interest means that for every $100 placed in a savings account, $5 gets added to the account every year. For every $200 placed in a savings account, $10 gets added to the account.

$100 x 0.05 = $5.00

$200 x 0.05 = $10.00

Compound interest

If the interest earned is not taken out of the account, i.e., a total of $105 ($100 + $5), then this new total earns an interest of five percent equaling $5.25. The five percent

compounded interest has earned more than the five percent simple interest.

$105 x 0.05 = $5.25

$210 x 0.05 = $10.50

While 25 cents may not seem like much, it will be a noticeable difference to your child. You can explain that in the long term and when savings amounts are larger, the interest earned will add up.

Show your children that if, for example, they have saved up $7,000 from approximately eight years of lai see and another $500 from savings on allowance for a total of $7,500 ($7,000 + $500), then simple interest (at five percent) would yield $375 ($7,500 x 0.05), while compound interest would yield $393.75 ($7,875 x 0.05) in the second year.

Tell them again and again that the more they save, and the longer they save, the more they will get in return. Just as importantly, these returns are generated without having to do anything (no paid chores, no part-time jobs, etc.). In fact, these returns will only be generated if they do nothing (no going out, no shopping, etc.).

Accounting professionals recommend that when deciding on a savings rate for your “Bank of Parents,” be sure to keep the following in mind:

Offer an obviously attractive savings rate or incentive (e.g., one percent per month). The rate should be high enough so that your kids can quickly see the results of saving.

Use a monthly or quarterly time frame because one year may be too long for your child’s attention span.

Octopus card

Just as “Bank of Parents” prepares your children for real banks, Octopus cards prepare them for real credit and debit cards; do not shy away from them and use them. From an accounting point of view, the main benefit of an Octopus card is that it’s a debit card, as opposed to a credit card and like an allowance, your kids will only be able to spend what is stored on the card. Additionally, they will learn to make the association between plastic and debit, as opposed to plastic and credit—an association that could serve them in the future. Again, if they decide to use up all the value on their cards for treating friends to ice cream or bus rides, let them decide and deal with the consequences. This mother shares how she taught her daughter:

“My daughter decided to be nice and treat several of her classmates to some lollipops and pretty much used up half of her card’s value. Afterward, she came home and happily told me what she had done. I explained to her that while generosity is great, she needs to learn how to strike a balance and know her limits.

“She needs to realise that she cannot give away without thinking even if the intention is good. I also let her know that she needs to weigh the pros and cons. This idea applies to charitable donations as well so I figured it was a sensible point to make.”

From a parent’s perspective, it makes sense to set specific yet loosely regulated rules for Octopus card usage. For example, the card is to be used primarily for public transportation, even though it can be used for other common purchases such as snacks.

Principles of saving also apply to the Octopus card because whatever amount is not used from the monthly additions (highly recommended as it is similar to an allowance) can carry over to the next month. Whatever is not used is saved, and you and your child might consider depositing these savings in the “Bank of Parents.” One parent says it’s difficult to decide:

“I personally do not agree with paying interest from Octopus card balances because in the real world, card companies do not hold such practices. But I do have friends who choose to do so as an extra effort to get their kids to save more money.”

Buying and shopping guide

Parenting advisors point out that as an extension to the want versus need philosophy, comparative shopping and impulse shopping can be used to train your children about disciplined and smart buying.

Using your head, controlling your heart: comparison and impulse shopping

To show your children the value of comparison shopping, take them through the aisles in a supermarket and look for the best purchase based on price and quantity. They need to not only look for price, but also learn to distinguish between paying $10 for two pounds as opposed to $8 for one pound. You can vary this exercise with any form of shopping and with any product in the store.

The impulse shopping exercise takes comparison shopping one step further. Help your children find the best price and then ask them to decide whether or not they really want it. For example, if your child wants to buy a new book bag because the current one is no longer trendy (but still perfectly functional), encourage them to shop around and look for prices.

After coming to the conclusion that it may take four months of savings to buy something they already have, your child may decide against it. The point of the impulse shopping exercise is to guide your child through his or her thinking process regarding spending their own money. There is no “impulsive” factor if it is Mommy or Daddy’s money. Again, allowing your kids to make mistakes is an excellent lesson.

A mother talks about her surprise when she tried this exercise:

“We were walking around a toy store one day and my son started begging for a new robot. He kept telling me that all his friends have this specific one and that if he didn’t have this one, even though he already had three robots, he wouldn’t be able to be friends with them.

“I told him he would have to pay for it himself because I had already bought him a robot. I also told him to shop around and look at prices before deciding which one to buy and he calculated that it would take two months of allowance to buy this new robot.

“Given that he thought he was going to lose some friends by not having this robot, it was surprising to me that he quickly decided to give this one up. The good thing is that he was able to overcome his own impulses instead of having me do it for him.”

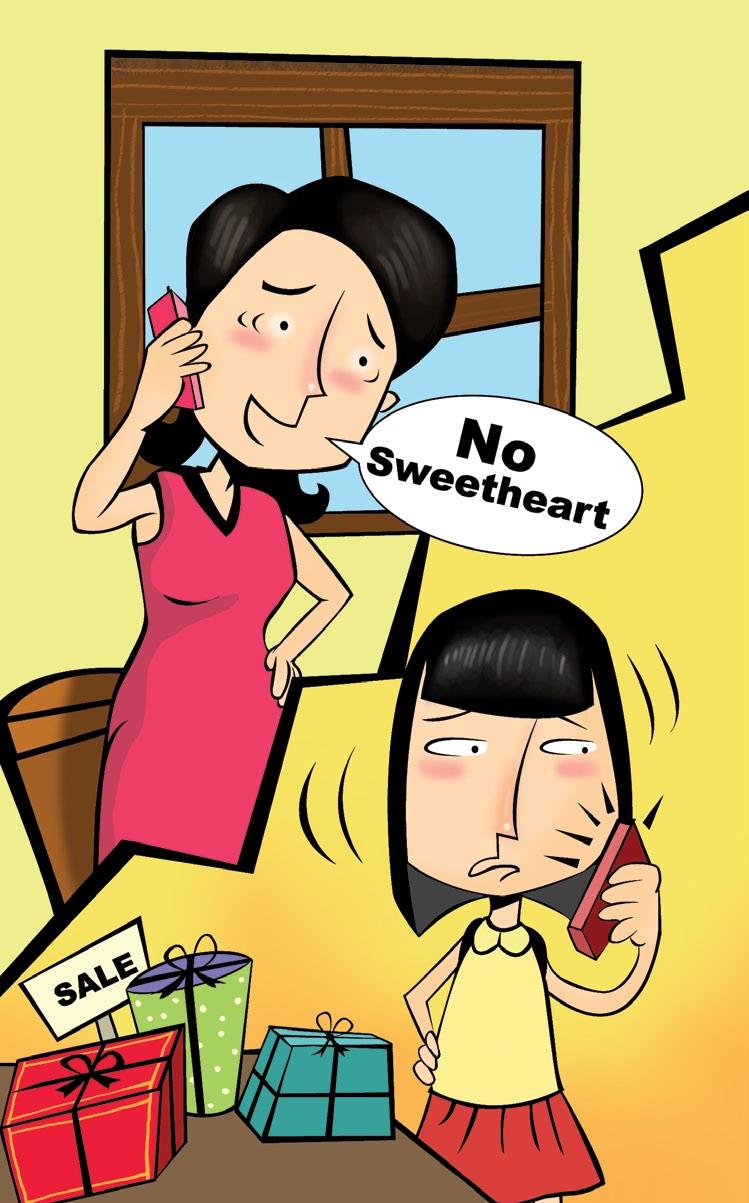

For those parents who tend to buckle to their children’s whims, it’s hard to say “no.” Saying “no” to your own children is especially hard when all they ask for is a small toy or a chocolate bar. However, the value of these “no’s” will serve them well down the line. As a compromise, instead of flat out saying “no,” offer something else, for example a hug, in return. A hug may not have the same value as a toy at that moment but over time, your children will learn to realise that a hug is worth more than any toy. It’s a difficult but worthy task, as this father explains:

“My kids are in university now but I remember when they were younger, it would pain me so much to have to say ‘no’ to them to teach them discipline. Sometimes they would only ask for

some candy or a small toy and the disappointment on their faces was at times unbearable for me.

“In essence, I was a pretty strict parent. But much to my happiness and amazement, at his university graduation dinner my son said to me, ‘Thanks, Dad, for all those times you said no to me.

“’It helped me develop a discipline that most of my friends don’t have.’ A sense of vindication and even catharsis hit me so hard I almost started crying.”

United front

Once you learn to say “no,” the next step is to make sure that as parents, you present a united front to your children. If one of you says “no” but the other says “yes,” then the lesson is destroyed and your children may in turn learn how to manipulate you: If Daddy says “no” but Mommy says “yes,” you’ve got a problem.

As the saying goes, “it takes a village to raise a child,” it is also vital that you coordinate with your child’s grandparents, aunts, uncles, and godparents about saying “no” to your kid.

Just as your children can learn to manipulate you, they can also learn to manipulate others who care for them. Set up some sort of system for all relevant parties where approval must come from you or your spouse. Not only must parents present a united front, the “village” must as well. This woman explains:

“My husband and I were very cautious about not being manipulated by our kids so we decided that, even before having kids, we would always work together and be on the same wavelength. So whenever I said ‘no’ he did too.

“But it turns out, for better or worse, our son noticed that grandma would always say ‘yes’ because he was her first grandchild, so he ended up going to her a lot of times. It got to a point where he and grandma actually had their own secret pact where she would buy something for him and he would hide it from us. Needless to say, he wasn’t very successful and we caught him easily.

‘Afterward, we had a nice long chat with grandma and actually convinced her that siding with us would in the long run benefit him and teach him some valuable lessons.”

Money for chores or grades

Parenting experts are generally divided into two schools of thought on the concept of paying for chores or good grades: One school believes payment is the most direct and obvious way to let children know they are doing a good job and the right thing. Another school of thought believes children need to learn that chores and grades are their responsibilities, not things from which to make a profit.

You might consider some compromises. For example, money rewards for grades and chores outside of your child’s normal responsibilities are sensible and motivational.

Anything extracurricular, such as a science fair or a writing contest, could be rewarded monetarily because such activities fall outside the scope of personal academic responsibility (not to mention that in the real world, many contests use cash rewards to attract the best talent). However, doing homework, going to school or acing a test should not be rewarded with money because these activities are within the boundaries of personal academic responsibility.

On the other hand, walking the dog or washing the car could be paid chores if they fall outside the scope of personal household responsibility. However, making their beds or taking a bath does not merit monetary rewards because they are personal household responsibilities.

Money vs. no money

These examples might give you a few more ideas:

Money reward

Winning a tennis tournament

Winning a spelling bee

Helping to paint the house

Setting up electronics

No money reward

Getting into a dream school

Getting an A in math

Cleaning their room

Baby-sitting siblings

For those parents who are a little more willing to go out on a limb, there is a third school of thought: As long as your children are capable of doing whatever chore it is, this is all that matters. Many Hong Kong families have domestic helpers or family assistants and the issue of chores is often moot and the line between paid and unpaid chores is usually blurred. Does it make sense to ask your child to do something when a domestic helper is paid to do it?

Some, though very few, parents go as far as not hiring a family assistant so that their children can learn to do their own chores. But whether or not this is a practical tactic depends on individual families. The thinking of some parents is that as long as their children know how to perform chores and take care of themselves, it is enough because the focus should be on whether their children are independent and self-sufficient.

A Hong Kong parent explains how she thought it through:

“I’ve read a lot of books and consulted many experts about the issue of money for chores and grades. Grades are relatively easy to figure out because studying is all my kids do and they should be self-responsible about it.

“But when it comes to chores, it’s grey because the presence of our helper makes it much harder to distinguish between paid and unpaid chores. Some books and experts advise that paid chores are ones that a parent would pay for anyway. Thing is, we have a maid and we pay her to do everything, so does that mean we should pay our kids to do whatever the maid does?

“That doesn’t seem to make sense, so we figure the best way is simply to make sure that our kids know how to operate a washing machine or wash dishes or vacuum.

“We just want to make sure that they know how to take care of themselves. With our kids, it hasn’t been much of an issue because they actually see chores as fun as it’s something that they don’t often get to do and sometimes they get to play with grownup toys. For example, my son really loves to vacuum because he sees it as a toy that makes a lot of noise.”

Domestic helpers and family assistants

Oftentimes, family assistants double as babysitters and even language tutors as most of them speak English. Given the amount of time your family assistant spends with your children, it would make sense for you to coordinate with him or her as daily money monitors. Even if you set up an allowance system for your children to stay within budget, having the help of a daily monitor can add value to your child’s financial responsibility—particularly for busy parents.

Many parents agree that the issue of a family assistant needs to be discussed at length with your children because the presence of a family assistant lessens their household responsibilities, giving them fewer chances to contribute to the household in obvious ways such as ironing and sweeping. As such, you should take time to consistently and openly communicate with your children to let them know that the family assistant is there for the family and not just them. A number of parents have stressed the importance of making sure the children know that when Mommy or Daddy are not there, the family assistant—or someone you trust— is in charge.

What it was like for a man when he was young:

“Growing up, I knew that when mom or dad wasn’t around, the maid was in charge. She was number three. When I was a kid, I hated it.

“But now when I look back, I see the value of having an authoritative figure around. Having her around made me feel like I couldn’t just go wild even when my parents were gone.”

Teach the lesson in time

Seasoned accountants with children of their own say whether children are to be punished or rewarded, for whatever reason, the issue must be dealt with as soon as possible because short attention spans do not allow for certain lessons to be taught later. This parent gives an example:

“I remember during one of my business trips, my seven yearold daughter had lied to our helper about something. I decided that I would ground her for a week once I got back because there was no point in grounding her when I wasn’t around.

“By the time I got back, not only did I barely remember my reason for wanting to ground her, she had completely forgotten what she had done wrong in the first place. Even if I had grounded her, the lesson would have been lost.”

Given the schedules of working parents, dealing with your kid’s issues in a timely manner is easier with advancements in technology such as 3G phones. This type of technology allows you to stay in touch with your children even when away from home. For example, 3G phones let you see each other even if you are in a different country and in a worstcase scenario, if both parents are out of town, 3G phones allow for conference video calls.

As of now, internet-enabled services already allow free long-distance talk from anywhere in the world and certain services are developing free video conferencing. It is just a matter of time before free and easily accessible methods of communicating anytime and anywhere become widely available.

Technology helps, according to this father:

“Because of my job, I’m on the road a lot. As much as I miss my daughter, I can’t be there for her. But one good thing is that technology allows me to stay in touch and maintain a presence at home. I bought two 3G phones just to be in touch with her.

“Some of my other friends who also travel a lot for work haven’t used the technology yet and though there’s no documented or scientific proof, my daughter still has an attachment to me whereas for some of my friends, their children are visibly shy around them.”

Ultimately it’s important that your kids know that you are always accessible to them no matter how busy you may be.

Age 10 -12

By this age, most children will have developed the basic computer skills allowing them to navigate the web and operate simple software programmes. In fact, your kids may be even more advanced than you—given that they are exposed to computers and high technology at an early age.

On the home front, most children will have experienced the basics of financial responsibility in the form of “Bank of Parents” and Octopus cards. They are now ready to apply what they have learned and experienced.

Opening a bank account

After years of training through the “Bank of Parents” (and giving them incentives with artificially high interest rates), it is now time to move on and experience the “real deal.” Some banks in Hong Kong such as HSBC and Hang Seng allow joint accounts for children and their parents.

Experts advise you to take your children with you to the bank when opening the account so that they can actually see what is going on and associate a bank with what happens there—money transactions.

Many parents use a bank account to help their children develop an individual sense of ownership and responsibility. These concepts are clear to most children when they see their personal savings book, an online bank account, or perhaps their own ATM card. Banking has been a useful teaching tool for this parent:

“My daughter has a savings book with her name on it. Even though it is a joint account with me and I have the same savings book with my name on it too, she still feels that the account is hers. The sense of ownership and belonging is very important to kids and this is one way to go about it.”

Many parents open both a savings and checking account with their children so they get the full banking experience. Let them research, on their own, the different interest rates offered by different banks and help them learn about common banking products, such as timed deposits. The independent research is important for kids because this is the only way the information will stick. Initially, all this talk about timed deposits and interest rates may sound a little too advanced for many of your kids, but you and your children have a handy learning tool in the Internet and the information superhighway.

Cell phones

In Hong Kong, cell phones are literally everywhere with a penetration rate of more than 100 percent, and there are more mobile phones than people. It’s not uncommon to see children as young as late primary school age talking on or sending SMS’s through mobile phones.

You and your child may have already talked about the issue of cell phones, questioning whether or not your child really needs one. Needing versus wanting a mobile phone is an issue unto itself but a cell phone is a good tool for teaching financial responsibility.

You and your children may feel that mobile phones are unavoidable. A mobile phone can be purchased for need’s sake (from a communication and safety perspective), but when talking about the newest or trendiest phone with a camera and MP3 functions, then we’re certainly talking about want.

One way to talk to your child about wants and needs when it comes to the cell phone is to discuss who pays for the phone and who pays for the plan. This is good for teaching children about not taking the phone for granted and learning to be responsible for their own possessions.

You could work out a deal with your children where the phone itself is a gift, but the payment plan is their responsibility. This will help prevent abuse and give them partial responsibility.

A parent on cell phones:

“The cell phone issue for me is quite valuable as a teaching tool. In Hong Kong the cell phone illustrates the lessons of responsibility and discipline in the same manner as the car would in the U.S.—even though it is on a comparatively smaller scale.”

The world is a learning oyster

According to social workers at the Tung Wah Group of Hospitals, based on their experience working with families in debt, instilling the right attitude is more than half the battle in teaching financial responsibility.

After all, day-to-day decisions such as taking a bus instead of a taxi or not spending what you don’t have are not difficult to do or understand; the difficult or complicated part is to comprehend that these are only parts of the financial responsibility formula. The Tung Wah people have these tips for cultivating and reinforcing the right attitude toward financial responsibility:

Enrol your children in community service trips during the summer or as family vacations. Orphanages serve as ideal community service targets for children because they can relate to the audience—children. Working with other children can further reinforce the fact that money and affluence, or having parents or a family for that matter, are not things to be taken for granted.

Some parents tend to avoid trips to underdeveloped countries thinking that these places are not worth visiting or are not relaxing as vacation destinations when every place has something to offer. Teach your children to give something a chance before giving up or not liking it. There should not be a rule where they have to like it or enjoy it, but there should be a rule where they at least try it.

Give your children the chance to learn about foreign currencies and exchange rates and maybe even let them figure out the family spending budget for the trip. This way, they will feel that they are part of the process and you could expose them to another aspect of financial responsibility.

Dealing with extremes

We have talked about cultivating the right attitude as the basis for financial responsibility. Experts also indicate that cultivating the right attitude also helps in dealing with extremes. In some cases, your children may have peers from extremely affluent or ostensibly poor families. What should you do when your children have friends whose families are much wealthier or much less wealthy than your family? Much of it depends on how you view these extremes. And they can be extreme, as this Hong Kong graduate explains:

“I went to an international school where many of Hong Kong’s rich and famous went. Even though my family was well off it was still nowhere near the ridiculous wealth of some of these other families. We’re talking about a line of chauffeured Mercedes Benzes and Rolls Royces after school. A girl had a cell phone in the late 1980s when they ran in the tens of thousands of dollars price range and absolutely no one else had one.

“I distinctly remember one friend’s dad bought her a yacht when she turned 16 and I remember getting lost in a friend’s house until one of her six maids pointed me in the right direction.

“But the one thing I will always remember is that my parents reminded me to not only look at what they had but also to look at what they didn’t have.”

A teacher adds her view:

“Based on my experience as a local secondary school teacher, children from lower income families tend to fall into two extreme camps: role models and non-role models. Role models know how

to protect themselves and be tougher, which is probably why many of them do not like to be given sympathy or charity. They tend to be much more assertive and always seem to be on a mission.

“Oddly enough, I’ve also found many of them to be much more generous than their more affluent peers.”

Money = Trust = Communication

Veteran social workers from the Tung Wah Group agree that most money issues reflect trust issues. If you decide to control a child’s money or spending, it is most likely because you do not trust your child and you end up limiting the lines of communication.

To build a relationship based on trust, communicate and try not to control. That said, do not talk to them as if they were adults, talk to them as if they are the kids they are.

Many parents in the accounting profession believe the earlier children are exposed to family finances, the better. This includes controversial and sensitive issues that families have a tendency to hide, such as an uncle who gambles too much or a distant relative who went bankrupt.

Explaining this problem to children, especially at this age, helps them grow and mature.

It can be a wonderful experience, as these men say:

“I hit a rough patch back in the late 1980s when the markets really tanked. It got to a point where the family lifestyle had to change. I was really afraid that my son wouldn’t be able to handle it given that just several years earlier, I was doing better and better.

“Much to my surprise, he proved to be resilient and supportive and understanding. When faced with a potential school

change, he just rolled with the punches and let me know that he would be able to handle it.

“He was in tears, but he put on a brave face and showed me that he would be supportive. I almost broke out in tears.”

“When I lost my job, my son said he would forgo his allowance and take up a part-time job. He had just turned 11 at that point. I couldn’t believe the maturity he demonstrated.”

Conclusion

This book begins on a note of richness and we trust it leaves you with a feeling of enrichment.

As experts in financial responsibility, the Hong Kong Institute of Certified Public Accountants understands that the process of teaching your children financial responsibility is exactly that, a process. Moreover, it is a process that at times will be frustrating, at times will be patience-testing, and at times seems to be never-ending; but equipping your children with basic financial management skills will help them time and time again throughout their lives.

And for families...

The Hong Kong Institute of CPAs runs the “Rich Kid, Poor Kid” project, aimed at teaching Hong Kong families financial management concepts and practices. The project is supported by the Institute’s Accountant Ambassadors, who use their professional expertise as the “success ingredients” in Hong Kong’s family life.

Activities under the “Rich Kid, Poor Kid” project include surveys about family views towards money, road shows in secondary schools, storytelling in primary schools with May Moon and the Secrets of the CPAs and more.

For more information, please visit www.richkidpoorkid.com.hk.

And be sure not to miss...

An illustrated storybook for ages 8-12 about the true importance of money: how to earn it, how to keep it, and how best to use it.