23 minute read

Through a Modern Lens

THROUGH A MODERN LENS GROPIUS AND HIS PHOTOGRAPHER by MATTHEW DAMORA As a child, Matthew Damora frequently assisted his father, Robert, on photographic assignments on location and in the darkroom. Since the death of the elder Damora in 2009, Matt has been restoring his father’s photographs and making them available for publication and exhibition.

It feels like an error in destiny that I never met Walter Gropius. When he died in 1969, I was thirteen years old. While my childhood memories are not as comprehensive or as vivid as those many claim to enjoy, I think I would recall an encounter with Gropius. Where the likeness of a deity might hang, a portrait of Gropius was prominently displayed in my parents’ home. In third grade, a teacher asked my sister the identity of her religion (a politically correct question then). My sister proclaimed, “Architecture.” In our secular home, Gropius was God. All photographs by Robert Damora © Damora Archive, all rights reserved.

In 1947 my father, architectural photographer Robert Damora, wanted to meet Walter Gropius. The house that Gropius built in Lincoln, Massachusetts, in 1937 was designed to be as much a statement on residential design as to be a residence for the Gropius family. A decade later Dad felt the house had yet to be photographed and published in a manner allowing the public to fully appreciate its beauty and livability. Dad contacted Gropius to offer to photograph the house. Gropius accepted. The shoot took a month. Dad moved into the house and lived with the Gropiuses as their guest during late September and early October 1947.

Robert Damora was born in 1912 in New York City into a family steeped in the arts and sciences. His father was an architect, engineer, and inventor: an Italian aristocrat who immigrated to the United States to escape the social confines of his homeland. Grandfather married a beautiful young fellow Italian immigrant from the peasant classes. Grandfather’s family in Italy disowned him for his rebellion. He died in the influenza pandemic of 1918, leaving his young wife alone with two small children.

Dad had ingrained artistic talent. He worked from childhood to help support his family; employed in a hardware store he was swiftly tasked with designing the window displays. Seeking more satisfying employment as a teenager, he apprenticed with John Adams Davis, an esteemed photographer in New York City. Dad submitted an essay on the comparative architectural qualities of the Chrysler Building and the newly built Empire State Building to clinch the job. Dad left Davis to become a cameraman for photographically illustrated fiction novellas—essentially cinematographic undertakings executed in stills. He had a fierce independent streak, however, and opened his own studio in 1935 at the age of twenty-three.

Initially, Dad’s studio shot product stills, portraits,

and fashion. He did a particularly brisk business in promotional shots of the interiors of restaurants and retail stores. This work led him to analyze the manner in which architectural interiors were generally depicted in photography at the time, which he felt was too flat. He began exploring compositional techniques to bring the illusion of the third dimension into the depiction of three-dimensional spaces in a two-dimensional medium. He later dubbed this “volumetric photography.”

Dad was always drawn to architecture, perhaps because it was the primary vocation of the father he barely got to know. In 1932 he attended the seminal Modern Architecture: International Exhibition at the recently founded Museum of Modern Art in New York City, the traveling show MoMA organized to introduce the work of such European architects as Le Corbusier, Mies van der Rohe, and indeed, Walter Gropius and

the ideas of the Bauhaus to the American public. Dad later said that seeing this exhibition “hit me like a ton of bricks!” He soon enrolled in architecture classes at New York University, the first school in the United States to explore modern architecture.

In the five years before the United States entered World War II, he became a leading photographer of architecture in the northeast, contributing to the era’s foremost architectural periodicals like Architectural Forum, as well as popular shelter magazines such as House & Garden. He devoted this platform to advocating for Modern architecture and continued to develop both compositional approaches and technical photographic advancements to enable the public to fully experience spaces to which they lacked access. For example, his placement of elements (maybe a piece of furniture, a sculpture, a plant, or a pool of light) that become visual reference marks for spatial depth in a composition is a signature innovation. Dad developed methods of lighting to balance the subdued illumination of the interior scene with the brilliant daylight of the exterior landscape visible through the walls of glass

page 10 An evening shot of the Gropius residence entrance: “If it (the home) is well designed, it is probably living in sympathetic harmony with its surroundings,” Robert Damora said in Commercial Camera Magazine (vol. 4, no. 4, 1952). “The photographic interpretation should demonstrate this fact.” below Dad wrote the following about a shot of a living room built with expansive walls of glass, but I think his thoughts are applicable to this shot of the Gropiuses’ screen porch as well. The use of shadows articulates the path of natural light into the space and joins the table settings in establishing a mood for the time of day. “In good architecture, there is a cause for every effect,” he said in the same issue of Commercial Camera. “For example, the large glass surfaces shown… are there to let light in and, if you will, sight out. The light and the view are the causes; the windows, the result. To do justice to this design the photographer had to show both.”

Ise Gropius relaxes on the second-floor deck. Dad sought to make buildings alive for the viewers of his photographs. He never forgot that buildings are for humans to inhabit: his photographs not only reflect that but also rejoice in it. He would observe the exterior of a house (and interiors for rooms which become sunlit) for days to see how the sunlight at different times of day would present the house, then wait for the exact moment when house, sun, and clouds fell into harmony.

that were incorporated into many Modern designs. The very narrow latitude in the light sensitivity of photographic film and limited postproduction editing capabilities in the predigital era made this a challenge. Many of the significant architectural photographers working at the height of the midcentury modern period gave Dad credit as the primary innovator who deeply influenced all of their work.

Dad spent the war years in service directly attached to the Navy’s Special Devices Division of the Bureau of Aeronautics under Admiral Luis de Flores, developing methods of photographic reconnaissance, while also working with famed photographer Edward Steichen, commander of the Naval Aviation Photographic Unit, on public exhibitions of naval technological advancements.

Dad retreated to the Vermont woods to paint after the war, but soon needed to resume making a living. Entering 1947 he was looking for assignments that would garner widespread notice to help his photographic studio resume the prominence it enjoyed prior to the war. There was also his lifelong desire to pursue becoming an architect himself, which felt more urgent in the wake of the war. He regarded Walter Gropius, founder of the Bauhaus, to be the philosophical leader of the Modern movement, from which the architecture Dad was most passionate about stemmed. Offering to photograph the Gropiuses' house free of charge seemed a good way to initiate a relationship with him. The offer was unusual: Dad always had a client (typically a magazine) before

undertaking a shoot. This is the only portfolio he shot on spec in his career.

Given Dad’s painstaking approach to photography, each shot at the Gropius house may have taken a day or more. The Gropiuses helped in staging the house. They all got to know each other quite well. Ise, Walter’s wife, traded a recipe for triple-boiled German coffee for that of Dad’s mother’s southern Italian spaghetti. Dad asked Walter and Ise to appear in some shots. The Gropiuses’ daughter, Ati, and her fiancé, Charles Forberg, visited during the shoot and were swiftly drafted to model in the view of the stairwell. Walter sat for a lengthy portrait session.

My mother, Sirkka, at the time an editor of architecture at House & Garden and courting Dad (she later became an architect and Dad’s professional, as well as a personal, partner) accepted an invitation to tour the house and meet Gropius. Sitting in the garden on a beautiful afternoon with Walter and Dad talking about birds, local nature preserves, and discussing the photography, Mom recalls that Walter spied a squirrel invading his bird feeder. Walter pulled a small rifle from under his chair. Dad, displaying his urban-born, nature-lover’s sensibilities, said, “Oh, don’t do that!” Walter shot Dad a withering glance and proceeded to summarily dispatch the interloper. A squirrel may be just a rat sporting a pretty tail to a former World War I cavalry officer, but Dad had trouble reconciling Walter’s reflexive action with his preconceived notion of the man he revered. I have heard that Ise was reputed to be the better shot.

On receiving prints of the finished photographs a couple of weeks after Dad’s departure, Walter wrote to him, “We all were absolutely delighted about your really superb photos” and “It is a beautiful set with extraordinary understanding of space. The great patience you have had in preparing them has indeed been worthwhile.” Ise wrote, “It was a happy time with you and I cherish that photo of myself on the roof deck. It just shows all the happiness I always feel in Lincoln.” Walter ordered numerous sets of prints over the succeeding twenty years. The portfolio of eighteen released photographs became Gropius’s official presentation of the house.

Asked fifty years later about his approach to photographing the central stairway, Dad responded:

“The process of my photography of great architecture always consists of (1) the need to do justice to the subject at hand, and (2) the equal compulsion to reflect the attitudes and objectives of the architect or designer involved.

“For me, photographing the Gropius house was like stepping into my subconscious where the familiar artifacts and images of my well-worn books on Gropius—his early architecture and industrial design, the Bauhaus, Harvard—leaped off the pages into intense reality. These images became a definite part of the photograph; it was impossible to concentrate on the stairway alone.

“The result, of course, became the duality of two forces, past and present, working together to articulate the total design.”

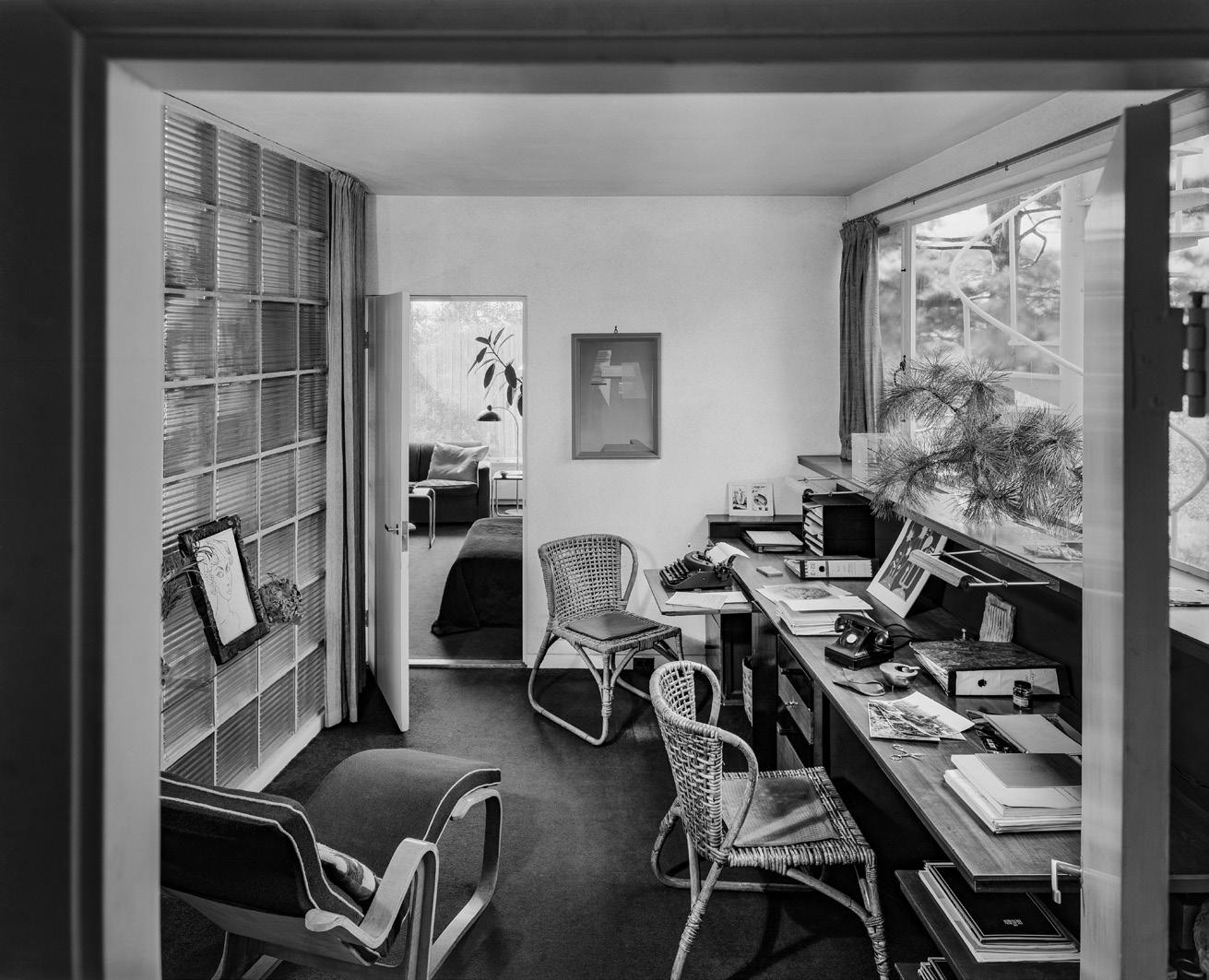

The first U.S. publication of the photographs was in House & Garden magazine for the January 1949 issue. (Gropius had placed them in a couple of European publications prior to that.) Katherine Morrow Ford (a well-known author on Modern architecture) was “First of all, a home is a place where people live, so that some place in the picture there must be evidence of people,” Robert Damora said in Commercial Camera Magazine (vol. 4, no. 4, 1952). Beyond witnessing signs of daily life, the viewer is often drawn to imagine inhabiting a particular spot within the space depicted as in the chair behind the typewriter here: “a place for a person even though it is not filled,” the photographer added. Walter and Ise Gropius shared this home office.

the architectural editor of House & Garden at the time. Dad had worked with her before and Mom was Ford's associate editor and “Girl Friday.” Gropius and Marcel Breuer had designed a house for Ford and her husband, James, built in 1939 around the corner from the Gropius house. There was no definitive arrangement for an article prior to the shoot, but considering that everyone knew each other, it is possible the idea was kicked around. Everyone did collaborate on the final article, titled “Ten years’ experience with our house.” Walter and Ise wrote the text. Prior to the prominence of television, popular magazines

like House & Garden enjoyed huge audiences. The article was very widely and positively received, bringing great attention to the house and to Dad’s photography.

Dad’s photographic practice did experience the rejuvenation he was seeking and he covered many noteworthy projects of the immediate postwar Modern period by such notables as Mies van der Rohe, Marcel Breuer, Eero Saarinen, Philip Johnson, Ulrich Franzen, John Johansen, Paul Rudolph, Vincent Kling, Hugh Stubbins, I. M. Pei, Henry Cobb, and Florence Knoll. By 1951 he had also enrolled in the Yale School of Architecture to finish his architectural degree.

In this shot, Dad used models—the Gropiuses’ daughter, Ati, and her soonto-be first husband Charles Forberg—to articulate the path of movement through a space. He partially obscures the models in adjacent rooms to enhance that expression without blocking your view of the architecture or distracting focus from it. The slight tilt of the camera is an almost film noir technique Dad would occasionally employ to give the illusion of looking up at or into a building.

In the 1960s his recognition as a photographer faded as he shifted his focus to his own designs for which he received awards, including an American Institute of Architects (AIA) Award of Merit, the House of the Year from Architectural Record magazine, and Guggenheim, National Endowment for the Arts, and AIA fellowships. The AIA also recognized him with the 1965 Gold Medal for Architectural Photography.

Dad and Walter stayed in touch until the end of Walter’s life. Despite the difference in their ages (three decades), as well as in their social and professional statures, I think it is still fair to say they formed a friendship. Dad photographed projects for Gropius’s firm, The Architects Collaborative. Walter became a mentor as Dad launched his own architectural practice. Prefabricated construction methods were a subject of great interest to them both; Dad became an innovator in this approach. Walter gave advice and provided recommendations. “Mr. Damora is an accomplished architect whose professional work I consider of the highest quality,” Walter said. “I consider him the best photographer of architecture in this country.”

Visit gropius.house/topics/ the-lincoln-house/ to view more historical photographs of Gropius House.

Abolition, Suffrage, and the Activism of

Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin

by KABRIA BAUMGARTNER The author of In Pursuit of Knowledge: Black Women and Educational Activism in Antebellum America (New York University Press, 2019), Kabria Baumgartner is an assistant professor of American Studies at the University of New Hampshire, Durham.

In 1860, eighteen-year-old Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin was one of 126 abolitionists to sign a Massachusetts state petition against the federal Fugitive Slave Law of 1850, which required citizens to help slave owners recover self-emancipated, or so-called fugitive, slaves. Like many antislavery petitions, this one designated “legal voters,” or men, to sign in the left column while “other adults,” or women, signed in the right. Despite this gendered division, women petitioners like Ruffin exercised their right to protest unjust laws and assert their political will, however limited. Over the next few decades, Ruffin’s activism deepened, working as journalist and editor, participating in charitable work on behalf of children and African Americans, and mobilizing public support for a grand political goal: women’s suffrage.

Many African American women activists championed suffrage for a host of reasons: to advance the race; to gain power and influence; to win “respect and protection,” as educator Nannie Helen Burroughs argued in a 1915 issue of The Crisis, the magazine of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. Other arguments included Editor’s Note: In 1919 Congress passed the Nineteenth Amendment granting American women the right to vote. All but seven states in the South ratified the amendment the following year. This article launches Historic New England magazine’s recognition of this revolutionary milestone in U.S. history. Women had waged a difficult, near-century-long struggle to win enfranchisement. This struggle for civil rights and equality posed peculiar challenges for African American women, who were distinctly burdened by the intersectionality of gender and race.

From the New York Public Library

bolstering social, economic, and educational policies; and asserting equality and civic independence. Charlotte Rollin of South Carolina, who with her four sisters was among the most influential black women activists during Reconstruction, may have summed it up best when she addressed a women’s suffrage meeting in Columbia, South Carolina, in 1871. “We ask for suffrage not as a favor, nor as a privilege, but as a right based on the ground that we are human beings and as such, entitled to all human rights,” she told her audience. For many suffragists, this struggle for human rights was a continuation of earlier activist campaigns such as the abolition movement, the fight for equal education rights, and the women’s rights movement.

African American women were forerunners in the fight for women’s rights. Some seventeen years before the 1848 women’s rights convention in Seneca Falls, New York, Maria W. Stewart, an African American

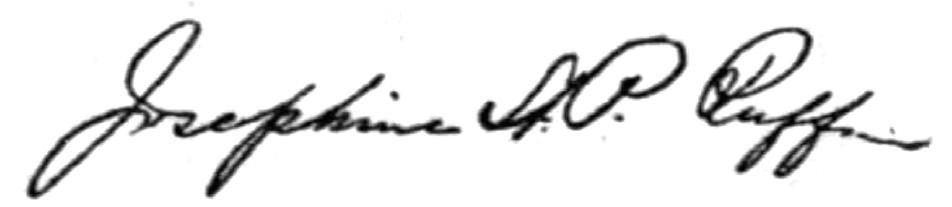

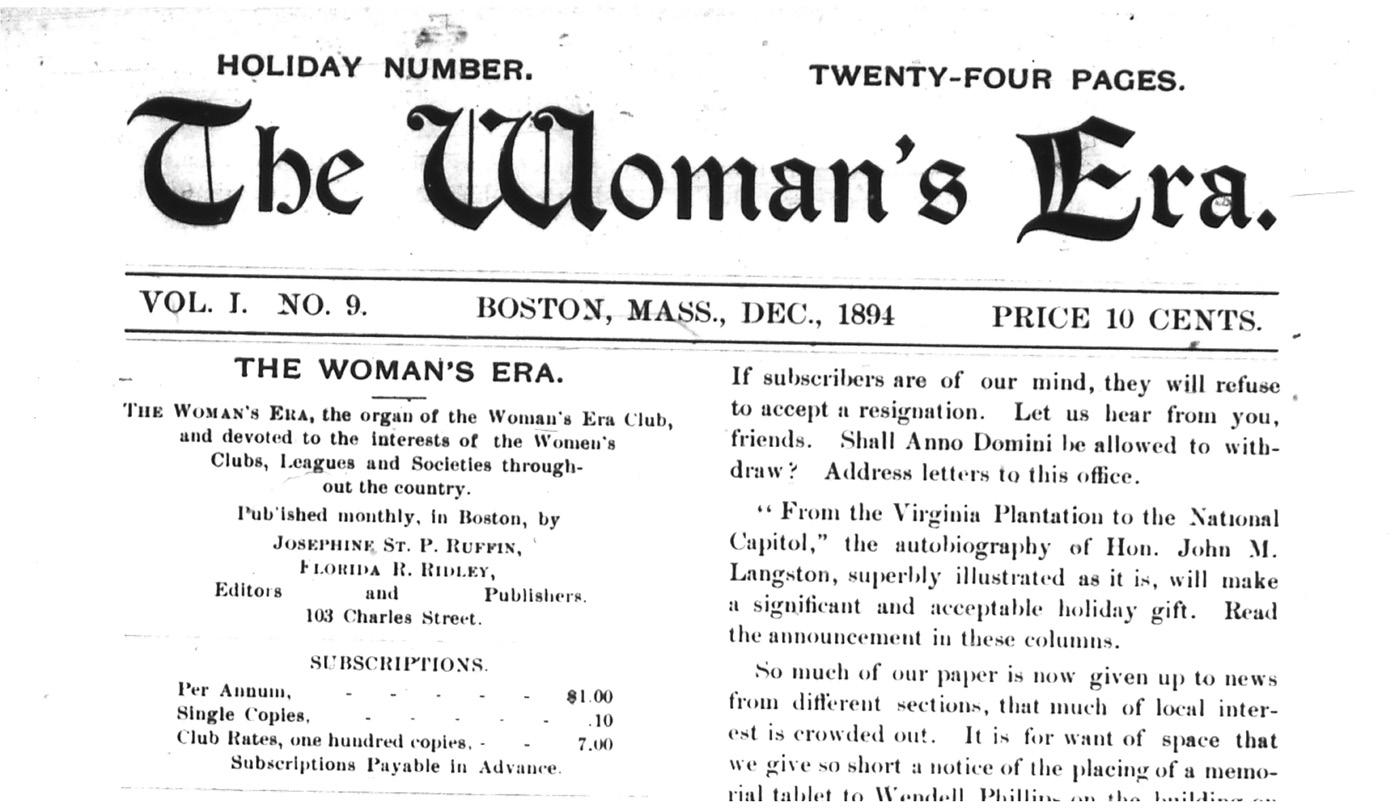

page 15 The tablet commemorating Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin is at the Massachusetts State House. It is one of six pieces installed as part of the State House Women’s Leadership Project to honor selected women who made major contributions that benefited American society. above Ruffin established the Woman’s Era Club of Boston during the nationwide black women’s club movement of the late nineteenth century. Serving as club president, she founded The Woman’s Era newspaper, a nationally distributed monthly that advocated for African American women’s education, employment, and suffrage. The newspaper also focused on quality-of-life issues and advocated involvement in anti-lynching efforts. Ruffin and her daughter, Florida Ridley, served as editors. (Newspaper Collection, Boston Public Library.)

teacher and likely the first Americanborn woman to speak publicly about political issues to an audience of black and white men and women, published a pamphlet encouraging African American women to persevere in the face of adversity and “sue for [their] rights and privileges.” In 1858, an interracial coalition of 277 women and men from Nantucket petitioned the Commonwealth of Massachusetts for women’s suffrage. (They signed their names in a single column rather than follow the gender-based convention mentioned earlier.) Among the African American women signers were fifty-eight-year-old Charlotte D. Morris, an abolitionist; Elizabeth R. Nahar, a forty-year-old seamstress; and Eunice F. Ross, a thirty-five-yearold activist who had led the fight for equal education rights on Nantucket in the 1840s. Whether through print culture or collective political participation, African American women fought for political inclusion well before the outbreak of the Civil War.

As the nation passed from a state of war to a state of reconstruction, the debate over black suffrage resurfaced. The ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment to the Constitution in 1870 gave male citizens the right to vote regardless of “race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” White suffragists Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton could abide neither this exclusion nor the fact that African American men had won the right to vote before white women. The women’s suffrage movement splintered, with two separate organizations forming: Anthony and Stanton established the National Woman Suffrage Association, which opposed the Fifteenth Amendment, and suffragists who backed the amendment joined the American Woman Suffrage Association, led by white abolitionist Lucy Stone.

Keenly aware of the complex

interplay between race and gender, African American women suffragists carefully crafted their remarks in response to the ratification. While famed orator and women's rights activist Sojourner Truth believed that enfranchising African American men placed African American women in a servile position, she reframed the debate to highlight the necessity of black women’s suffrage. So did Mary Ann Shadd Cary. An educator, journalist, and lawyer, Cary backed the Fifteenth Amendment, all the while criticizing it for its failure to enshrine women’s suffrage. She even cited the Fourteenth and Fifteenth amendments in her own suffrage petition to the District of Columbia in the 1870s. The Fifteenth Amendment certainly provoked dissension, but for some African American women suffragists, it was a milestone in the broader struggle for universal suffrage, that is, voting rights for all citizens regardless of race or gender.

Full enfranchisement at the state and national levels remained elusive in the 1870s. In Massachusetts, for instance, women gained the right to vote in school board elections in 1879. Other states, including New Hampshire, adopted school suffrage laws, too. Why were women allowed to elect education officials but denied full voting rights? Perhaps state legislators conceded school suffrage as a convenient measure amid the rising tide of women’s activism. Whatever the case, in 1880, Boston women suffragists, including Lucy Stone and Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin, organized the Massachusetts School Suffrage Association with the aim to increase female voter registration and support strong school committee candidates.

In 1896, the Silver Democrats— proponents of an economic policy

“A silent but active revolution is in progress among the colored women in the United States.” —Suffragist and schoolteacher Elizabeth Carter at the first National Conference of Colored Women, July 1895, Boston.

that called for using silver as a monetary standard in addition to gold— put Ruffin at the top of the ticket for the Boston School Committee. The nomination showed that discriminatory attitudes had changed somewhat since 1851, when Ruffin and her siblings were expelled from the city’s schools because of their race. Ruffin attended the integrated public schools in Salem, Massachusetts, before completing her education in Boston, which banned public school segregation in 1855 following a petition campaign. Given her sinuous path to schooling, Ruffin valued her right to vote in school board elections. She argued that women were a powerful voting bloc, wielding influence in educational affairs from city to city.

African American women suffragists continued to mobilize in the late nineteenth century, establishing civic organizations, creating newspapers and magazines, and speaking out in public protest, all the while asserting their role as civic actors. Ruffin was an exemplar. In 1892 she founded the Woman’s Era Club, which was devoted to the intellectual and moral improvement of African American women. Over 100 women joined the club, including Maria Baldwin, a Cambridge, Massachusetts, schoolteacher and principal; Ruffin’s daughter, Florida Ruffin Ridley; and even a few white women. Indeed, Ruffin’s platform was rooted in a principle of racial inclusion, which was why she was surprised when the General Federation of Women’s Clubs, a nationwide coalition of thousands of white women’s groups, denied her admission at its convention in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, in 1900 because she was affiliated with an African American women’s club. The controversy this sparked was reported widely in the press and became known as the “Ruffin incident.”

The “Ruffin incident” did not dampen the work of the Woman’s Era Club, which contributed to the growing African American clubwomen’s movement. In one of her last lectures prior to her death, Lucy Stone urged members to “help make the world better,” which became the club’s motto. Women’s suffrage typified that motto. In an article published in the Boston Globe on March 4, 1894, Ruffin took up the following question: “Are New England laws unjust to women?” Her response was a resounding “Yes.” She added, “It would seem that there are a few rights given to men yet denied to women, but none, however, that the use of the ballot could not, either directly or indirectly, affect.” Ruffin’s remark had less to do with the notion that women’s suffrage was a panacea and more to do with the belief that unjust laws that affected women, or anybody, could be undone by exercising one’s vote.

Ruffin extended her influence further when she created The Woman’s Era newspaper, her club’s official organ. As the first newspaper with

a nationwide readership edited by African American women for African American women, it reported on pressing issues like lynching, and it featured poetry, short stories, and reports on women’s political activity in states such as Colorado and Illinois. Ruffin also used the pages of her newspaper to dismiss antisuffragists who maintained that a “woman will lose her womanliness” if granted full enfranchisement. She proudly endorsed the image of the new woman who could vote and whose vote mattered.

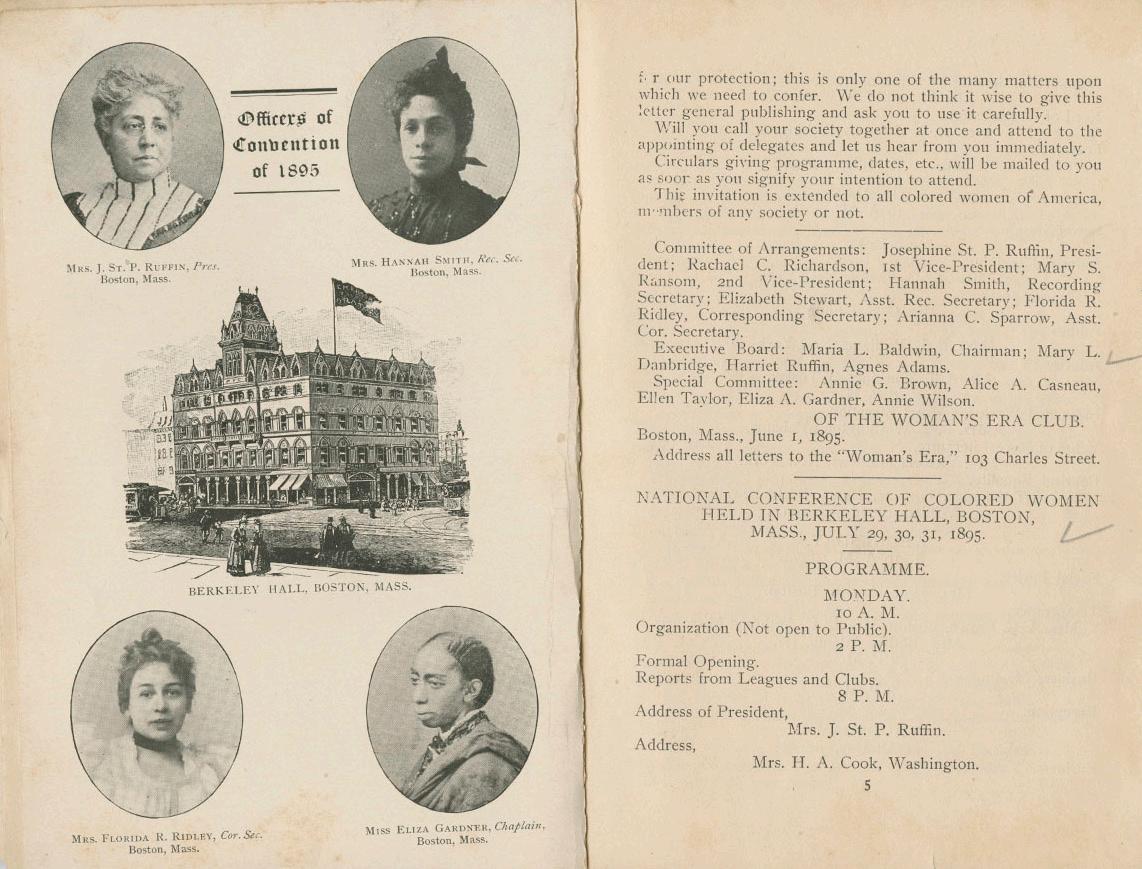

The idea to organize a national convention for African American clubwomen came to fruition in July 1895, thanks to the formidable work of Ruffin. At Berkeley Hall in Boston’s Back Bay, representatives of fifty-three clubs from nine states gathered, including notable educators Anna Julia Cooper and Mary Church Terrell as well as anti-lynching activist Ida B. Wells Barnett. A historic event, this convention sparked the establishment of the National Association of Colored Women in 1896. “A silent but active revolution,”

declared African American suffragist and New Bedford, Massachusetts, schoolteacher Elizabeth Carter, “is in progress among the colored women in the United States.”

The Crisis, which was edited by the African American intellectual and writer W. E. B. Du Bois, devoted part of its August 1915 issue to the women’s suffrage movement. Twenty-six preeminent writers and activists, including Ruffin and Maria Baldwin, expressed their views. Ruffin sought to allay the doubts of some anti-suffragist African American men by arguing that fighting for gender equality bolstered racial equality. Baldwin predicted that full enfranchisement would empower teachers and benefit education. The women’s suffrage movement continued to achieve victories as a dozen states granted women voting rights by 1917.

Two years later, Massachusetts ratified the Nineteenth Amendment and by 1920, thirty-five other states did, too, giving American women the right to vote. Ruffin's efforts were not forgotten among African

Ruffin issued a “Call to Confer” exhorting black women around the country to participate in a national convention, which was held in July 1895 at Berkeley Hall in Boston. The primary aim of the three-day conference was to establish a national organization for black women, which they named the National Federation of Afro-American Women. After merging with other African American women’s groups around the country, the organization became known as the National Association of Colored Women. It incorporated in 1904 as the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs, using as its motto, “Lifting As We Climb.” Today, chapters are active in forty-nine states and the District of Columbia. The program of the first convention (left) featured photographs of the officers. Pictured clockwise from the top left are Ruffin, the convention president; Hannah Smith, recording secretary; Eliza Gardner, chaplain; and Florida Ridley (Ruffin’s daughter), corresponding secretary.

American women, who organized literary clubs bearing her name and even taught “Ruffin Study” classes on parliamentary procedure.

In March 1924, Ruffin passed away at the age of eighty-one. Although women’s suffrage had been enacted by then, continued activism remained vital as African American men and women faced intimidation, threats, and violence, not to mention unjust laws like the poll tax that proscribed their ability to exercise voting rights, particularly in the South.

A commemorative bust of Ruffin now adorns the wall outside Doric Hall in the Massachusetts State House. As lawmakers, residents, and tourists walk past, they read Ruffin’s wise words: “If laws are unjust, they must be continually broken until they are killed or altered.” In the face of unjust laws such as the Fugitive Slave Law or the denial of women’s suffrage, the vote—fought for and then proudly wielded by women like Ruffin—was a righteous weapon of both defense and justice, the history and value of which must be remembered today.