5 minute read

Media Intervention

Home Movie Media Intervention How to keep recorded memories from degrading Similar scenes captured in home movies across decades and formats. From left, composer/pianist Leopold Godowsky, 1938, 16mm film (courtesy of the Leopold Godowsky, Jr. Home Movie Collection); the author, c. 1986, 8mm analog videotape; and Ziva Raftery, the author’s niece, 2019, HD (high definition) digital video shot with cell phone.

When most people think of home movies, they picture a small film reel, probably 8mm or Super8, the content in all likelihood silent, the scenes short depictions of special occasions, the images in black and white or perhaps in brilliant Kodachrome color of the mid-twentieth century. These are the films we typically consider when we concern ourselves with preserving family home movies. But in reality, these types of home movies haven’t been widely created for forty years. So, what are we doing to preserve the videotapes and born-digital files that contain the home movies of the past few generations? And when we find those old film reels, which could now easily be over seventy-five years old, what do we do with them?

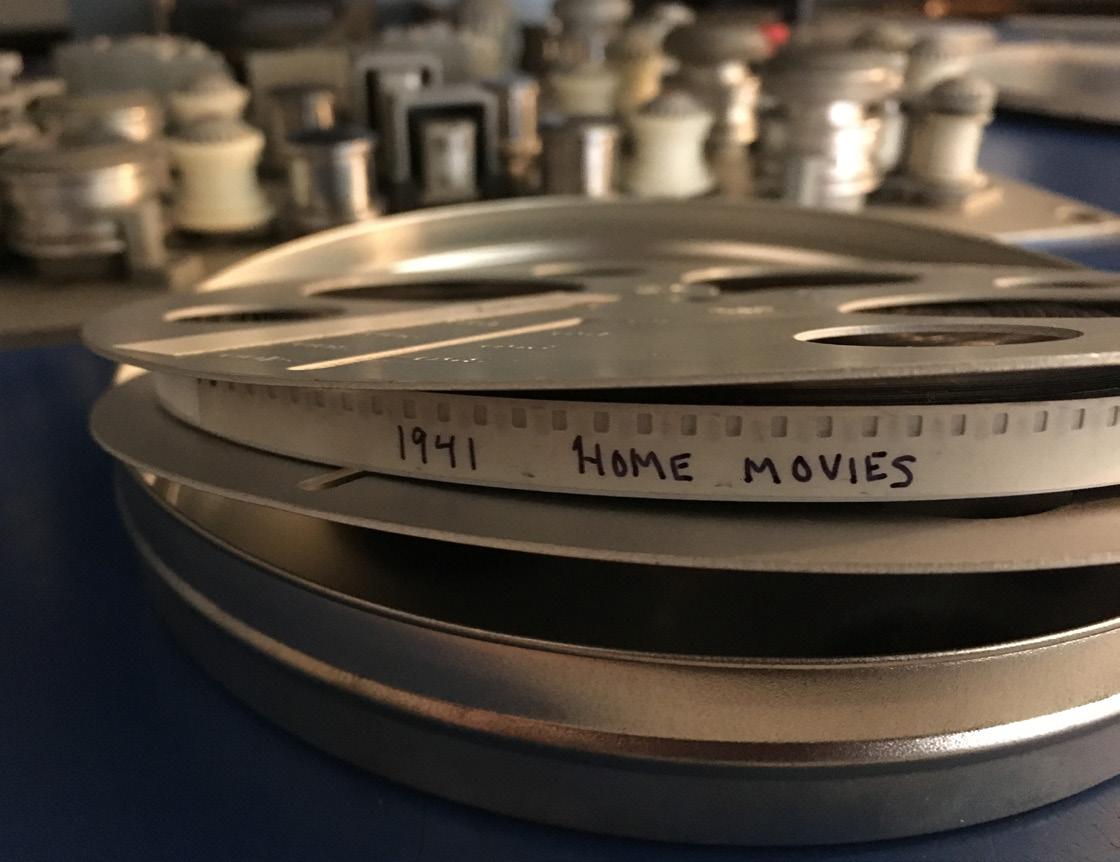

The good news about the film reels is that as long as they have been kept in a relatively cool and dry environment (please remove them from your hot attic or damp basement immediately!) they’re probably in decent shape. If you hold these filmstrips up to the light, there are images that you can readily see—celluloid film being the only moving-image format that generously allows its viewer to perceive it without a machine. To fully and easily access and share these home movies, use the services of a film scanning lab, which will convert the photographic images into digital ones. There are various technical specifications to consider depending on how you plan to use the home movies, but ideally, the films should be scanned at a minimum of high-definition resolution (1920 x 1080) and the files should be delivered in a format that has not been overly compressed. Be sure that the lab returns the original films to you, and continue to store them in a cool, dry place. Just because you now have digital files does not mean that you have “preserved” the films. Given how moving-image technology evolves, it is quite possible that a future transferring process could yield better results—think of the 1990s, when standard practice for making home movies accessible for families would have been to transfer 8mm films to analog videotape, most likely consumer-grade VHS (video home system), a far inferior visual format.

On the topic of videotape, the current buzz phrase and consuming fear in the audiovisual archiving community is the “magnetic media crisis.” Unlike with film, which at its core only requires light to make it legible, all of the home movies shot on videotape from the 1980s through the early 2000s require equipment for viewing. There is nothing to “see” on those tapes without the intervention of a playback deck that reads the images and sounds captured in the magnetic particles and sends them to some sort of monitor. My own childhood was occasionally recorded on Video8, a cassette format that came out in the by BECCA BENDER Film archivist and curator of recorded media at the Rhode Island Historical Society

1980s and served as an alternative to the small-sized VHS tapes (VHS-C) that fit into cassette adapters for playback in standard VHS VCRs (video cassette recorders). Neither of these analog cassette formats—or any magnetic media, including open reel audio and digital videotape—has the capacity for long-term archival storage (e.g., more than thirty years). Magnetic tape is highly prone to deterioration, causing signal loss, and the required playback equipment is more or less obsolete; even the ubiquitous VHS VCR hasn’t been manufactured since 2016. If you still have a VCR lying around and try to play your VHS home movies, don’t be surprised if they look staticky and repeatedly “drop out.” The best thing to do is to send your tapes to a transfer lab as soon as possible to get the media into a digital format.

Given that digitization is the recommended solution for accessing home movies originally shot on film or videotape, and that it’s the primary manner by which we all capture home movies today, it is particularly distressing that in many ways digital is the most at-risk moving image format of all. Consider the following: Had you already downloaded the videos from your 2011 phone before you dropped it in a lake? (I had not.) If you did download them, are the files on a computer that you still own? Or are they on a DVD that simply says “pics,” and perhaps no longer loads? Does your computer still have a DVD drive? Or are the files on a hard drive with a cable that doesn't plug into your current computer? Has that eightyear-old hard drive failed? Are the digital files encoded in a video format that your current computer can play? Are there so many files on your current phone that you can’t bear to organize them? Are any of those files named in a way that tells your future self what the content is (i.e., not IMG_2864.mov)? What about your descendants? Compared to the handwriting on the Kodak film box that says: “Paul & Carl birthday 1951,” is there any way for someone who finds this digital video fifty years from now

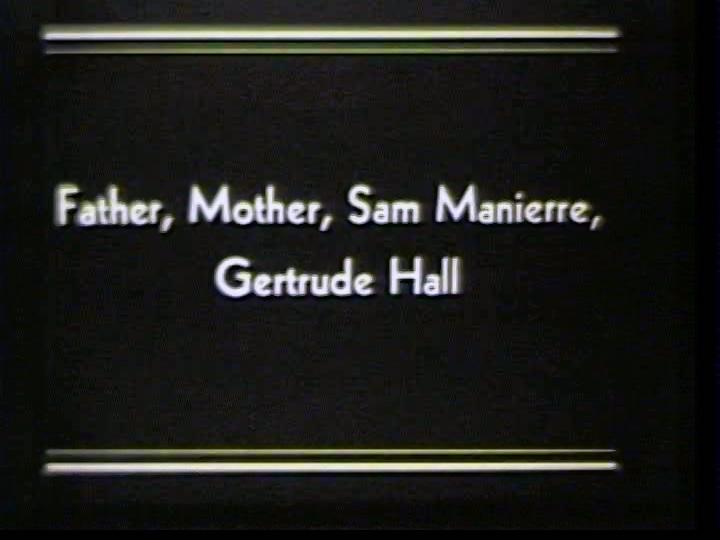

The Rhode Island Historical Society Film Collection consists of more than nine million feet of moving-image film from early Rhode Island film studios, local news stations, and home movies. Some home movies were shot with 8mm film (left) and some were made using 16mm film (below).

to know what they’re looking at? Can they trust the date stamp embedded in the digital file—is it really the date the video was shot or is it the date someone moved the file using a program that doesn’t retain original metadata? You get the idea.

Without going into a full-scale personal digital archiving lecture (the Library of Congress and others have good online resources), here are some key takeaways: v Curate your digital files shortly after creation; if you shoot five videos of the same thing, keep one. v Rename the files as though you were writing a caption on an old photograph “2019_ZivaPianoRecital.mov.” v Organize your files into digital folders using a system that will be meaningful in the future. v Keep at least two copies of your files, ideally in two different geographic places. v Check your hard drives periodically to make sure they still mount and check your video files to see that they still play; expect to replace your hard drives every five or so years.

Home movies can hold rich cultural value beyond the family in which they were created, particularly if they depict communities that are typically underrepresented by the mainstream creators of media. National collections such as the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture are gathering home movies to tell stories from a community-based perspective.