9 minute read

A Historical Perspective

airlines is clearly on the wane. Foreign-trained personnel do not appear to be much of a factor in U.S. aviation labor markets, perhaps because foreign airlines who often pay for training themselves are not likely to train large numbers of pilots beyond their own immediate needs. Nor has ab initio training been adopted much by U.S. airlines, most likely because its high cost does not seem justified as long as there is a substantial applicant pool of pilots trained in the military, collegiate programs, and on-the-job training.

This leaves on-the-job training and collegiate-based programs as the pathways that seem most likely to replace military training as the primary route to the major airlines. The committee expects that collegiate aviation increasingly will dominate on-the-job training because it can produce higher-quality pilots that are better able to adapt to changing technology. Collegiate aviation education, which embeds technical training in a broader foundation of learning, is potentially well suited to preparing workers who can adapt to new technology, learn continuously throughout their careers, and operate effectively in the team-oriented environment of the modern cockpit and maintenance workplace. As the experience of pilot candidates in the 1990s already proves, collegiate aviation programs, combined with the more advanced training offered by specialized flight schools, present individuals with numerous options for accumulating the extensive qualifications that airlines require when the labor market is tight.

In the committee's view, a civilian aviation training system grounded in collegiate aviation education offers the most practical alternative to the decline of the military pathway. The key question then becomes: Can a civilian training system that depends heavily on postsecondary education institutions to prepare aviation's most highly specialized workers be expected to provide the numbers and kind of workers that the air transportation industry will need to operate efficiently and safely?

Challenges For A Civilian Training System

With the downsizing of the military, it is clear that the civilian training system will have to play a larger role in meeting the pilot and AMT needs of the airlines. The committee concludes that the civilian training system, dominated by the collegiate pathway, can meet the specialized workforce needs of commercial aviation, both in terms of the number of people needed and the quality of the training provided. Before the system is fully effective, however, several challenges will have to be addressed.

Meeting Airline Demand

The initial question posed by military downsizing is whether civilian training will be able to make up numerically for reductions of military-trained aviation personnel, and the committee concludes that the answer is unequivocally yes. In

< previous page page_98

If you like this book, buy it! next page >

FIGURE 4-1 Airline industry system revenue passenger miles (RPMs). SOURCE: Form 41 reports submitted to the U.S. Department of Transportation by U.S. certificated air carriers, as compiled by Data Base Products, Inc.

reaching this conclusion, the committee did not construct a formal model of the supply and demand for specialized airline employment. Constructing such a model is difficult, and perhaps even futile, while the industry is undergoing such a fundamental restructuring.

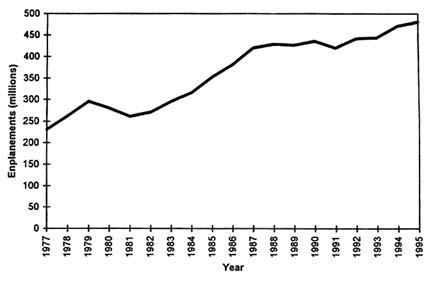

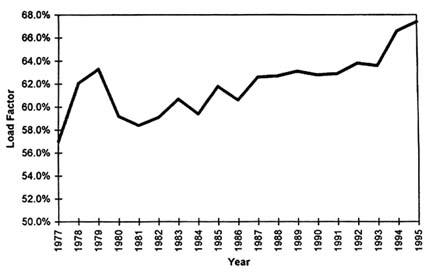

Figures 4-1 and 4-2 show revenue passenger miles and enplanements for the U.S. airline industry system (domestic plus international) during the years 1977 through 1995. By both measures, the story is one of reasonably steady industry growth in the aggregate in passenger travel. There was a dip following the onset of the fuel crisis in 1979 and another more modest dip in 1991. To be sure, individual airlines did not all fare the same; some grew faster than others, a few entered bankruptcy, and others faced greater variation in traffic carried.

The first step in forecasting the need for airline employees is to forecast the future levels of airline travel on U.S. carriers. Airline travel depends on a variety of factors. Macroeconomic conditions, including interest rates, disposable income, growth in gross domestic product, and so on, are a major influence. And of course a major determinant is the price of airline travel, which in turn is strongly influenced by the price of fuel, interest rates, and other cost factors and by the degree and nature of competition, including the price of competing modes of short-haul air travel.

Predicting future air travel levels is difficult, but once that is done, it is even more difficult to predict the impact on employment because the relationship

< previous page page_99

If you like this book, buy it! next page >

FIGURE 4-2 Airline industry enplanements. SOURCE: Form 41 reports submitted to the U.S. Department of Transportation by U.S. certificated air carriers, as compiled by Data Base Products, Inc.

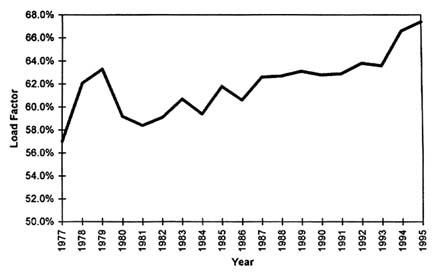

between the number of employees, particularly pilots and mechanics, and the traffic carried has been changing as the industry restructures to meet the demands of domestic deregulation and the changing international aviation environment. One factor used to try to predict the need for pilots and mechanics is the projected number of aircraft needed to carry passenger demand. But the number of aircraft needed depends in part on the load factors, which measure the percentage of airline seats that are filled. As shown in Figure 4-3, load factors shot up immediately after deregulation as airlines used newly gained pricing freedoms to fill seats, then they dropped sharply with the onset of the fuel crisis in 1979. Since 1981, however, the increase in system load factors has been fairly steady. Indeed, the load factors have increased in all but four years, and following each of those four years they reboundedand morethe following year. What will the load factors be in the coming years? Will they continue to rise? By how much and how quickly? Will they reach a certain level, then stabilize? What level and when? Or will the airlines intensify competition in a way that causes load factors to drop? When will they drop and how far? These are questions about which thoughtful and well-informed airline observers do not agree, but which are critical in forecasting the demand for pilots and mechanics.

Another critical issue is the average size of aircraft. One set of forces is pushing toward smaller aircraft, as airlines develop more point-to-point service overflying congested hubs. As air travel grows, however, there could be an

< previous page page_100

If you like this book, buy it! next page >

FIGURE 4-3 Airline industry system load factors. SOURCE: Form 41 reports submitted to the U.S. Department of Transportation by U.S. certificated air carriers, as compiled by Data Base Products, Inc.

opposing trend toward larger aircraft, as airports and airways become more congested and a growing shortage of new landing slots constraints the number of flights into key airports. Already the combination of local opposition and environmental concerns has made it increasingly difficult to expand airport capacity. These capacity constraints could be a particular problem in international service. Still another consideration is the aircraft crew requirement. Earlier generations of widely used aircraft, such as the Boeing 727 and DC-10, were configured for three-person flight deck crews, whereas the later generation of aircraft, such as the Boeing 757 and Boeing 767, were configured for two-person flight deck crews. These older aircraft can be reconfigured for two-person crews. Should that be done, the airline requirements for pilots could fairly quickly become lower than past practices would suggest. Even without this reconfiguring, these airplanes will eventually be phased out of service and are likely to be replaced with aircraft with two-person flight deck crews, again implying a lower pilot requirement than one might expect from past relationships between airline traffic and pilot requirements.

Taken together and subject to much uncertainty, these various potential developments suggest continued improvement in pilot productivity. The committee judges that there will probably be a continued upward drift in aircraft load factors. Despite countervailing forces, it seems likely that there will also be some increase in average aircraft size, as airport congestion limits growth in the number

< previous page page_101

If you like this book, buy it! next page >

of flights at key airports. Average trip speed may also increase, as air traffic control procedures are improved and aircraft are allowed to fly more direct routes. Finally, there is likely to be a further downward trend in the average size of flight deck crews, although the rate of change is difficult to predict.

One might also expect improved productivity for AMTs in aircraft maintenance and repair. Changing aircraft technology could reduce the number of AMTs needed to support a given amount of passenger traffic. Also, growth in the use of third-party aircraft maintenance services could change the pattern of employment of AMTs and may contribute to greater productivity through greater specialization.

For these and other reasons, the committee did not base its assessment of the ability of the civilian training sector to meet airline needs on models of supply and demand. Rather, we based it on the demonstrated ability of the training sector to adapt to changing needs. In this regard, the civilian training sector may find the future easier to deal with than the past. In the past, the airlines have shown a strong tendency to hire military-trained pilots first and to hire civilian-trained pilots only as the stock of available military pilots became depleted. Thus, the volatile demand for civilian-trained pilots was linked not only to variation in airline hiring needs but also to variation in the numbers of pilots leaving the military. In the future, with the number of military pilots substantially reduced, the civilian training sector should face a larger and less volatile demand.

A second reason why we believe that the aviation labor market will adjust to airline needs is that the airlines are in a powerful position to influence this market. A study for the Department of Transportation succinctly stated the situation as it affects pilots (and, we would argue, maintenance personnel as well): ''The supply of pilots is, to a large extent, within the control of the carriersbecause they can provide the training to qualify new hires for pilot positions" (U.S. Department of Transportation, 1992:40). At the extreme, U.S. airlines would have the option already used by so many of their foreign counterparts, to provide ab initio training for carefully selected but inexperienced job candidates. But nothing in the U.S. experience suggests that this sort of ab initio training policy will be necessary or likely. U.S. carriers have many intermediate options for influencing the number and quality of the candidates available to them, short of undertaking and paying for training themselves. Their actions during the hiring boom of the late 1980s, when shortages were widely feared, are harbingers of the steps they can and undoubtedly will take if they are faced again with the possibility of not having all the qualified candidates they seek. And it is worth noting that, even in 1993, when a serious downturn made prospects for airline employment seem particularly poor, the FAA granted 12,645 new commercial licenses, 6,126 new ATP licenses, and 18,401 new mechanic licenses (Federal Aviation Administration, n.d.: Table 7.17).

Throughout their history, U.S. airlines have not needed to be heavily involved in developing an adequate labor pool because sufficient acceptable workers