2 minute read

Solar Cells

Testing Battery Chargers

Testing your shore-powered battery charger to determine if it’s functioning is easy. With the charger turned off, do an open-circuit voltage test (as described in chapter 5) at the battery the charger is connected to. Turn the charger on and observe your voltage reading at the battery. If the charger is functioning, you’ll get a reading of at least 0.5 volt greater than the open-circuit voltage. If it’s not working properly, the charger may have a blown fuse. The fuse is usually accessible on the outside case of the charger and is easily changed.

Advertisement

One charger I’ve worked with, however (made by Statpower), locates the fuse inside the charger housing, necessitating partial disassembly of the unit to check the fuse. Check the manual for the charger on your boat to determine the exact location of the fuse.

If the fuse checks out, you may have a problem with the shore-power side of the circuit supplying the charger. Remember: Alternating current can kill you! Before starting to troubleshoot the battery-charger circuit, be sure to read chapter 11 of this book, and if you have any doubts about your ability, call in a professional marine electrician to help.

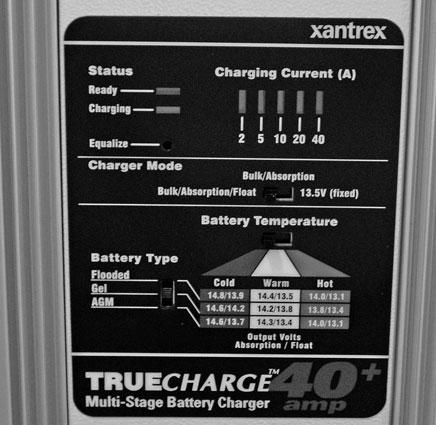

Figure 6-13 shows a state-of-the-art Xantrex multiphase smart charger. It also has a manual gel-cell, wet-cell, or AGM selection switch, a batterymounted temperature sensor, and switching parameters for different phases.

Fig. 6-13. Xantrex 40 amp charger.

Solar Cells

Solar panels are increasingly being used on some cruising powerboats to supplement other onboard charging systems. The silent energy that solar panel arrays provide is quite appealing to many boaters, and once installed, solar panels are virtually maintenance free. For boats that spend a lot of time at anchor away from the dock, and not much time underway, the 50 to 80 watts that medium-sized panels provide can be the difference between keeping the batteries charged up or running them down over time.

There are several important points to remember about solar panels. First, they do get hot sitting in the sun. If they get too hot, their output will actually decrease. Several years ago, when I was testing solar panels for Cruising World, I discovered that at noon on a July day at 42°latitude, the panels were being heated to 120°F, at which point their output began to diminish. So when mounting panels on flat surfaces, you must raise them above the surface to allow air to circulate on both sides of the panels.

Since a solar panel will allow a battery to discharge through the panel when the panel is not exposed to the sun, all panels must have a blocking diode in the positive feed from the charger to the battery. The diode lets current flow from the panel to the battery but blocks current flow from the battery back through the panel. On most panels, the diode is in a small box mounted at the output terminals on the back of the panel.

Finally, no panel should be installed without a charge controller—a fancy term for a voltage regulator—since the 15 to 20 volts a solar panel can produce is too much for sealed, gel-cell, or AGM batteries. Some charge controllers have internal blocking diodes, however, and you don’t want redundant blocking diodes since in marginal light situations the panel outputcould be reduced to a useless value (remember, diodes have an inherent 0.7 voltage drop through them). You can bypass or eliminate the blocking diode on the panel if the charge controller has an internal blocking diode.