21 minute read

Notes from the Brew Room Ann King

Soothing Bitters Ann King

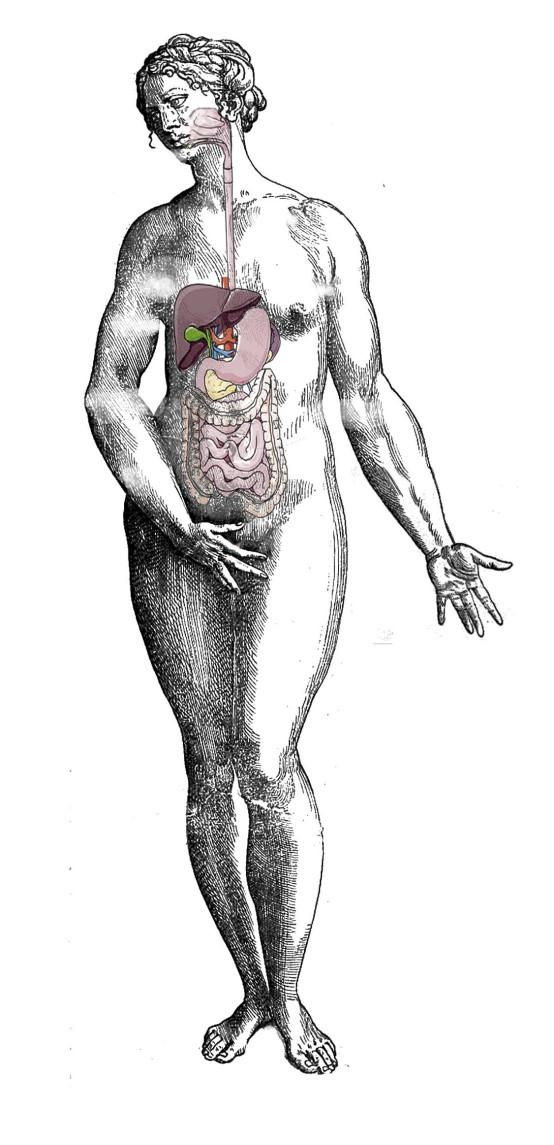

Current, fascinating research into the gutbrain-mood connection is particularly relevant when we also consider the effect gut health may have on the strength of our immune systems. The gut microbiome is the community of bacteria, fungi and other microorganisms that live inside our digestive tract. When these are in balance, the digestive system is able to break down food and extract nutrients in the most efficient manner possible. This, in turn, contributes to optimal functioning of the immune system, helping us fight off unwelcome microbes. A diet filled with unprocessed foods, high in pulses, whole grains, fruit and vegetables will benefit gut health. In addition, regular consumption of herbal bitters, often taken before food, can encourage the secretion of digestive juices, generally energise the gut’s systems, and act as a detoxifying agent for the liver. Experimenting with bitters is an exciting way to combine different flavours and herbs. Whilst traditionally bitter in taste, they can be augmented to create interesting pre-dinner aperitifs that will benefit digestion. Using herbs to aid digestion is by no means new; the digestif Chartreuse was produced by Carthusian monks as a medicinal liquor containing 130 botanicals which had been macerated for eight hours. It became popular in the 1800s as a calming and soothing postdinner drink. The favourite bitter in the Brew Room at the moment combines liver support, calming nervines, carminatives and antioxidant components to make a positive addition to daily wellbeing. So, here’s my ‘Soothe’ recipe— but please do experiment for yourself. Smell, taste, observe. Creativity will bring its own rewards. There are so many possibilities and permutations. At the end of the day, it all comes down to personal taste.

Advertisement

Ingredients 1 Orange (Citrus X sinensis)— unwaxed and preferably organic ¼ cup Calendula flowers/petals (Calendula officinalis)— for their gentle calming action and benefits to the lymphatic system ¼ cup Chamomile flowers (Matricaria chamomilla/ recutita)— a gentle bitter which modulates inflammation and decreases anxiety-based tension 5cm sliced, fresh Turmeric (Curcuma longa)— a cholagogue to promote bile secretion, and a hepatic herb 1tbsp Cardamom (Elettaria cardamomum)— for soothing the digestion and adding flavour 1tbsp Coriander seeds (Coriandrum sativum)— for its carminative properties and balancing notes 1tbsp Dandelion root (Taraxacum officinale)— to support liver function, high in nutrition 1 tsp Fennel seeds (Foeniculum vulgare)— a pleasant tasting carminative. 1 tsp Black Peppercorns (Piper nigrum)— a warming herb to encourage movement and increase the bioavailability of nutrients from other herbs in the profile ¼ cup local Honey Vodka ½ litre Kilner jar, or similar Method Simply chop up the Orange— flesh and skin — and combine with all the spices in a sterilised Kilner jar. Cover with honey, stir, and top up with vodka. Leave for one to two weeks, shaking and tasting every day until the desired taste is achieved. Strain through muslin and store in either dark glass dropper or spray bottles. Add a couple of drops to a glass of still or sparkling water and drink before meals. Shelf life: up to one year.

Disclaimer No recipes are intended to replace medical advice and the reader should seek the guidance of their doctor for all health matters. These profiles and recipes are intended for information purposes only and have not been tested or evaluated. Ann King is not making any claims regarding their efficacy and the reader is responsible for ensuring that any replications or adaptations of the recipes that they produce are safe to use and comply with cosmetic regulations where applicable.

Gut feelings

Anne Dalziel

People often know instinctively when a decision is the right one for them; they ‘trust their gut’, ‘know in their heart of hearts’. If someone is hesitant about a decision, they might ‘feel sick to their stomach’. We might describe someone with a low mood as a ‘misery guts’. Recent research into the connection between the gut and the mind (e.g., Vogt et al., 2017) is beginning to show there may some truth in these common sayings. Deepak Chopra (Chopra and Chopra, 2013), a neuroendocrinologist, writes: We started this whole idea of that wherever a thought goes a molecule follows. And the molecule is not just in your brain— it's everywhere in your body. There are receptors to these molecules in your immune system, in your gut and in your heart. So, when you say, ‘I have a gut feeling' or 'my heart is sad' or ‘I am bursting with joy,’ you're not speaking metaphorically. You're speaking literally.

Carabotti et al. (2015) describe a two-way signalling system, known as the ‘gut-brain axis’ that links the emotional and cognitive centres of the brain with the intestines. The balance of signals in these cerebral areas can affect the speed at which food moves through the digestive system, the absorption of nutrients, the secretion of juices, and the level of inflammation. The ‘second brain’ of the gut may also produce similar feel-good chemicals— like serotonin, melatonin, and dopamine. Conversely, negative emotions— anxiety, sadness, low mood, fear, anger —can also affect digestion. Sufferers of inflammatory bowel disease, irritable bowel syndrome, gastroesophageal reflux disease and food sensitivities often report their conditions worsen at times of stress (Lach et al., 2018).

The founder of the famous flower remedies, Edward Bach, was a bacteriologist who observed that certain intestinal germs had a close connection with chronic disease. Believing they also held the key to cure, he isolated the bacilli and prescribed it for the patient in the form of a vaccine. His work prefigures today’s research (e.g., Winter et al., 2018) which demonstrates that increased gut inflammation and changes in the microbiome can have profound effects throughout the body; contributing to fatigue, cardiovascular disease, and depression. At the same time, Bach studied the work of Samuel Hahnemann, the renowned homeopath. He was struck that Hahnemann had recognized the importance of personality in disease and soon noticed similarities between his work on vaccines and the principles of homoeopathy. He adapted his vaccines to produce a series of seven homeopathic ‘nosodes’. This work, and its subsequent publication (Bach and Wheeler, 1925) brought him some fame in homeopathic circles, and the Bach Nosodes are still used to this day.

By 1930, however, Bach had stopped this research, seeking a more holistic approach to medicine. He wanted to find more natural remedies, to treat emotional states. This led to the thirty-eight Bach Flower Remedies; ‘pure and simple herbs of the field’. These were never intended to treat physical illness per se, but to balance the emotions of the person. Bach Flower Remedies work on a vibrational level, with each of the remedies working to rebalance a specific emotional state. Bringing personal energy into harmony with the soul and the higher self creates emotional well-being

and freedom from such negative states as anger, uncertainty, fear, and despair. Once emotional balance and harmony are achieved, the path becomes clear for healing at the physical level. As Bach (1931) puts it: They... cure by flooding our bodies with the beautiful vibrations of our Higher Nature, in the presence of which, disease melts away as snow in the sunshine. So, Bach found that addressing the personalities and feelings of his patients unblocked the natural healing potential of their bodies and alleviated their unhappiness and physical distress. A keen observer of the human condition, he grouped patients’ personalities into seven categories, suggesting that each group reacted to ill health in particular ways. Likewise, he categorized the Bach Flower Remedies into seven groups: fear; uncertainty; insufficient interest in present circumstances; loneliness; over-sensitivity to influence and ideas; despondency and despair; and overcare for the welfare of others.

An example of a remedy in the despondency and despair group is Salix vitellina (Willow), and Bach (ibid.) suggests this is suitable: For those who have suffered adversity or misfortune and find these difficult to accept, without complaint or resentment, as they judge life much by the success which it brings. They feel that they have not deserved so great a trial that it was unjust, and they become embittered. They often take less interest and are less active in those things of life which they had previously enjoyed. Harbouring bitterness, pent-up anger, and frustration may contribute to various dysfunctions in the body. Continually being in a negative cycle of thoughts and feelings can disrupt mental and physical wellbeing. The Bach Flower Remedy is designed to gently help the individual to see their experience as the outcome of personal thoughts being projected into the outer world, and support their ability to change those thoughts to the

positive rather than the negative. Thus, this person ceases being a victim and becomes master of their own fate, beginning once again to enjoy life.

It is also appropriate to mention Ceratostigma wilmottiana (Cerato), which is in the uncertainty group of Bach Flower Remedies. The people who need this remedy are those who do not follow their gut feelings. In fact, they often ignore their own inner wisdom completely— relying instead on other people’s advice and ending up confused or doing something that they know in their heart is not right. The ambition of Cerato is to support the emergence of someone who listens to their own inner voice, is self-assured and decisive, and trusts their own judgement.

Of course, scientific research has greatly advanced since Bach first made the link between the gut and wellbeing more than ninety years ago. The world may have changed in that time, too, but human emotions and people’s reactions to everyday situations have not. Bach believed that the mind and body were connected and that is as true today as it was then.

Images courtesy of The Bach Centre

References Bach, E. (1931) Ye Suffer from Yourselves. The Bach Centre: Mount Vernon Bach, E. and Wheeler, C. E. (1925 [2020]) Chronic Disease – A Working Hypothesis. Read Books Ltd: Redditch Carabotti, M.; Scirocco, A.; Maselli, M. A. & Severi, C. (2015) ‘The gut-brain axis: interactions between enteric microbiota, central and enteric nervous systems, ‘in Annals of Gastroenterology 28(2):203-209 Chopra, D. and Chopra, S. (2013) Brotherhood: Dharma, Destiny, and the American Dream. Brilliance Corporation: Grand Haven, MI Lach, G.; Schellekens, H.; Dinan, T.G. & Cryan, J.F. (2018) ‘Anxiety, Depression, and the Microbiome: A Role for Gut Peptides,’ in Neurotherapeutics 15(1):36-59 Vogt, N.M.; Kerby, R.L.; Dill-McFarland, K.A.; Harding, S.J.; Merluzzi, A.P.; Johnson, S.C.; Carlsson, C.M.; Asthana, S.; Zetterberg, H. Blennow, K.; Bendlin, B.B. & Rey, F.E. (2017) ‘Gut microbiome alterations in Alzheimer's disease’, in Scientific Reports 7(1):13537 Winter, G.; Hart, R.A.; Charlesworth, R.P.G.; Sharpley, C.F. (2018) ‘Gut microbiome and depression: what we know and what we need to know,’ in Reviews in the Neurosciences, 29(6):629-643

Impatience with Impatiens

Ramsey Affifi

I was born and raised in a settler city sprawling through the middle of traditional Anishnaabe territory. Despite living and breathing land kept by Anishnaabe people, my education occurred within, and indeed maintained, a bubble separating me from this broader cultural world. I grew up with a love, admiration and care for the living world around me, and yet even here, my stock of concepts was influenced by people born to those across the Atlantic, not by the children and tenders of my own watershed.

Despite this all too familiar scenario, a number of concerns with the environmental narratives circling about crept into my consciousness. One concern was with the term ‘invasive species’, a label cast so casually by those within my bubble. Even if these creatures were shaking up existing ecological balances, it bothered me that adults taught children to vilify them under the guise of ‘education’. I wondered if the phrase victimised not only Garlic Mustard (Alliaria petiolata), Purple Loofestrife (Lythrum salicaria) and countless other animals and plants, but also the young recipients of these words, replacing the possibility of enchantment in their story of the world with experiences of judgment and division. When the xenophobic language of the populist right in Britain and North America regularly hit my social media feed, I couldn’t help but wonder whether the stock of metaphors used in politics was being imported into ecology. I was struck by an apparent contradiction: many of my environmentalist friends were appalled at the use of such language in the human realm but adhered to it unflinchingly in the field of the green, the feathered, and the furry.

How could the impulse to ‘other’ others be condemned in one context but taken up in another? I pondered whether something Jungian was at work. Even if invasive species were sometimes causing disturbance to local ecosystems, is calling them ‘invasive’, creating ‘eradication programs’ and all the rest of the militarism, really the best way to approach them? Are many of us settlers and globally mobile citizens unsettled in our depths about where we ‘should’ be living? Are environmentalists projecting onto other species a darkness within? What inner work do we need to do before treading into questions of how we might treat these prolific newcomers?

Now living in the land where my grandfather was born, and still not feeling quite at home, I stand at the edge of the Water of Leith, watching its inexorable flow under the crisp, winter sun. I imagine clusters of Himalayan Balsam (Impatiens glandulifera) clambering along its edges sometime after the summer crests and the days start shortening again. The government has occasionally called the Royal Marines in to destroy this showy, pink flower, and researchers are investigating new biological diseases to wipe them out. But bees have accepted this plant into their web of relations, delighting in what seems a joyous frenzy from its copious nectar. When does a plant— or a person —become native to a place?

Newspapers regularly remind us of ‘pollinator collapse’ set in motion by a collision of threats; from pesticide use to habitat destruction. Might Himalayan Balsam’s flourishing be part of ecological rebalancing rather than disruption? Few questions so quickly furrow my ecologist friends’ brows. Perhaps their irritation is warranted. Alongside other local species, bees seem to favour Himalayan Balsam (Horsely, 2016). The presence of Himalayan Balsam may thereby reduce the pollination of other species, some already curbed by its fecundity. But like many ecological studies, how we bracket our vision turns out to be crucial. A study must have a beginning and an end, and conclusions are drawn from within

these boundaries. While the results are in a certain sense objective, the decision of when to start and stop the study is not. In this case, as long as the Himalayan Balsam’s nectar exceeds the needs of the bee population, bees may well favour it to the detriment of other plants. But such a scenario is obviously temporary. At some point, Himalayan Balsam’s plentiful supply will increase pollinator populations, but will no longer meet the demand. Other less alluring food sources are then sought out. Davis (2011) calls this ‘the car dealership effect’. In recent years, some popular science books have argued that invasive species seem to cause fewer extinctions than previously assumed (Pearce, 2015; Thomas, 2018). Perhaps they jump in to fill opening niches and catalyse evolutionary change?

Others point out many invasive species run rampant because they have no natural predators. Maybe so, but the best way to ensure a predator develops is to let a would-be prey expand its range. If there is any ecological rule, it is that an unexploited niche is an evolutionary opportunity. It is not clear how long we’d wait for animal grazers to step in, but we can be confident opportunistic microbes will quickly emerge. Again, the question is timescale. People are currently testing fungi that might infect Himalayan Balsam (Tanner et al., 2015)— but we know that if we didn’t, something would evolve anyway. What is the rush? What kind of hero story do we need to maintain? Why do we need to insist that the intervention restoring balance come from us rather than nature? And how does this hero story link up with the villain story? Is there a tragic feedback loop between guilt and hubris? Instead of revelling in a nature increasingly manipulated to fulfil an image we’ve concocted from the arbitrary past, might we not become careful students and attentive lovers of the process by which ecosystems adjust and accommodate change? Is nature an active intelligent process or a static process to be preserved? Might ecosystems self-regulation exceed our comprehension? The biosphere, after all, evolved myriad creatures in complex co-existence with all their countless fascinating features. Surely the arrival of new species— be it through hitching on the backs of birds, on logs projected into the seas by violent monsoon rivers, or through continental merging —is nothing new in the story of the Earth. What role does patience, indeed humility, play in conservation?

With these thoughts in mind, I google how Anishnaabe people view invasive species. As many Anishnaabe people still live in intercourse with the land, I imagine invasive species might impact them more directly than urbanites who malign new species’ encroachments on their places of leisure. Reo and Ogden’s (2018) ethnography of indigenous Anishnaabe communities reveals some common features lacing through a wide variety of views and practices towards invasive species. Anishnaabe people are likely to view invasive species as migrating communities or, as they call them, nations. Many consider every nation to have gifts to share, and accepting their gifts fosters reciprocal responsibilities of care and respect. Human and more-thanhuman nations may not yet know or understand the gifts a new nation might bring to a place, but all have an active role in co-determining the new relationship that will emerge. So, whilst important food and medicines are often significantly affected by the arrival of a new species, for the most part the attitude is ‘let’s wait and see’. In other words, the process begins with listening.

Perhaps we need not wait for fungi or bacteria to make food of Himalayan Balsam. It has been around the British Isles long enough for many of us to know how delicious its yellow seeds can be. To me, they taste a bit like watermelon. If more of us consumed this offering with gratitude, their numbers might be controlled but not eliminated, and our community made the better for it. That might be a better lesson for our children.

References Davis, M. (2011) ‘Do Native Birds Care Whether Their Berries Are Native or Exotic? No.’ in BioScience, 61(7): 501–502

Horsely, C. (2016) ‘Alien invasions! Himalayan Balsam, friend or foe?’ in Buzzword 32, November 2016 Pearce, F. (2015) The new wild: Why invasive species will be nature’s salvation. Icon Books: London, UK Reo, N.J. & Ogden, L.A. (2018). ‘Anishnaabe Aki: an indigenous perspective on the global threat of invasive species,’ in Sustainability Science 13: 1443-1452 Tanner, R.A.; Pollard, K.M.; Varia, S.; Evans, H.C. & Ellison, C.A. (2015) ‘First release of a fungal classical biocontrol agent against an invasive alien weed in Europe: biology of the rust, Puccinia komarovii var. glanduliferae,’ in Plant Pathology, 64(5):1130-1139. Thomas, C.D. (2018) Inheritors of the earth. Penguin: New York

From little seeds…

Ruth Crighton-Ward

In March, new growth is noticeable; buds are appearing on shrubs and trees, the greens of plants appear brighter and more alive, and the seed sowing season starts in earnest.

When sowing seeds, it is advisable to use seed compost rather than regular compost. Seed compost is usually a bit finer than regular compost and is often sand based. You can make your own, using a mix of equal parts sharp sand, leaf mould and loam. Seed compost needs to be of less nutritional value than other compost, so that it is not too strong for the seedlings. It is finer, to make it easier for the seedlings to push themselves up through it. If making your own, you may have to take careful note of which seeds you sow in it. For example, if sowing a salad leaf mixture there will be a variety of different looking seedlings emerging. With homemade compost— unless it has been sterilised —the likelihood is that there will be a selection of weeds germinating alongside your desired plants. Shop-bought compost comes already sterilised. You can sterilize your own— in an oven or microwave — but this is not always very practical. Seeds come in all shapes and sizes, and they should be sown to the requirement of each particular type. Some will want to be sown at greater depth than others, and some should just be scattered lightly over the growing medium and not covered at all. Some will require a pot all to themselves. For germination to occur, the conditions must be right for that type of seed. Instructions are usually printed on seed packets. If not, do some research prior to sowing. This is applicable to all seeds— whether growing for food, medicinal or ornamental purposes. The attached series of photos shows the sowing of Tomato seeds (Solanum lycopersicum) in pots. These pots will only be home to the seedlings for the first couple of months. After that, the seedlings will be ‘pricked out’— moved into bigger pots. The seeds themselves are small and I have sown 4 seeds in each 10cm x 10cm pot. They should be sown shallowly— to only about an eighth of an inch. Then, cover them lightly by sieving some fine compost over them. Tomatoes are incredibly versatile, with a huge number of varieties to suit every space and gardener, and

a large range of flavours to suit every taste bud. Some are incredibly sweet, whilst others have a more earthy flavour. If your space is limited, there are many dwarf varieties which will produce ample quantities of fruit. They are one of our favourite salad and cooking ingredients, as well as containing an antioxidant called lycopene—associated with many health benefits, including reducing the risk of heart disease and cancer. Seeds sown last month should now have germinated. Seedlings are delicate, so watering should be done sparingly. With seed trays, water the seedlings from the bottom by placing the trays in a larger tray filled with water. Wait until they are wet through before lifting out. This is a much gentler method of giving them a drink than dowsing them using a watering can and potentially damaging them. Now is a good time to gently heat the soil for those seeds that will be sown directly outdoors next month. This can be done by placing horticultural fleece over the areas to be sown. Over time, this gradually reduces the chill and gently raises the temperature a couple of degrees.

Much of the garden would benefit from a feed at this time of year. This will give plants an energy boost as the growing season kicks in. There are many different types of plant feed, in liquid, powder, and solid form— go for ones that are natural, rather than chemical; seaweed, chicken manure or blood, fish and bone. But be aware of plants that prefer an ericaceous feed; these are acid-loving plants, like Blueberry (Vaccinium corymbosum). Although regular compost will not do them any harm, they would benefit more from a lower pH value. Acid plants tend to favour a growing medium with a pH around 6. The average soil in this country has a pH of 6.5 to 7, and anything above that is more alkaline. Seeing which plants grow well in different areas of the garden can be an indicator of the pH of your soil, or you can test it. Testing kits can be bought at garden centres or, for tips on making your own, just look back to the Chemistry Column in the December (12//20) issue of Herbology News.

Throughout March, the first crop of Potatoes (Solanum tuberosum) can be ‘chitted’, then sown. Chitting gives potatoes the best chance to grow and is achieved by sitting the seed potatoes in the light (but not direct sunlight) for approximately two to three weeks. This should be done indoors, not outdoors. Egg boxes are good here— they allow the Potatoes to sit and keep them apart from each other. Over the course of those couple of weeks, the Potatoes will start to produce growth from their ‘eyes’. When these new shoots are about an inch long, the Potatoes will be ready to plant in the ground. Next month, I’ll get into the detail of planting Potatoes, pricking out seedlings, transplanting into bigger pots, and the direct sowing of seeds outdoors.