12 minute read

vii Foraging Through Folklore Ella Leith

Which wych?

Ella Leith

Advertisement

Is there something witchy about Witch Hazel (Hamamelis virginiana)? It is a shrub that borrows other trees’ names. It is definitely not a Hazel tree (Corylus avellana), despite also being known as Snapping Hazelnut. Nor, despite its other name— Spotted Elder —is it an Elder tree (Sambucus nigra). There’s definitely magic in another of its bynames: Winterbloom, so-called for its bright and spiky flowers that arrive in the cold season and are somehow impervious to frost. Witch Hazel relies on wind currents rather than insects for pollination, so in theory it could appear anywhere— as if by magic. I’m not sure that I’ve ever seen the tree in nature, but I know very well the astringent remedy that my mother and grandmother swore by for grazes and blemishes. A dab of Witch Hazel would sting, but that meant the magic was working.

If it isn’t a Hazel, then why do we call it Witch Hazel? In The International Book of Trees (1993:132), Hugh Johnson explains its name: Hazel because of its soft, oval leaves like the nut tree’s; witch presumably from witch. Intriguingly vague. Why from witch? For the healing quality of the ointment derived from its bark? Or because, in its native North America, it has traditionally been used for water witching?

Water witching is the term popularly used in America for what we’d call water divining or dowsing: the use of two L-shaped rods or a forked stick to identify subterranean water. When passing over underground water sources, suddenly the rods cross each other or the forked stick ‘quivers, and … twists in [the dowser’s] hands and points downward with such violence that the bark peels off’ (Vogt and Hyman 1959:2). First recorded by the Romans (Vogt & Golde 1958:520), it appears to have increased in popularity in the 16th Century, due to German miners dowsing to identify mineral veins and precious metals. The practice came to be used in the tin mines of Cornwall and spread throughout the British Isles and from there to America where, in addition to seeking underground water and metals, practitioners have dowsed for missing animals and people, and to ‘determin[e] digestible and indigestible foods’ (Barrett and Vogt, 1969:197). The movement of the rods or sticks is now usually attributed to ideomotor responses (i.e., the person moves unconsciously), with successful discoveries considered coincidental— ‘in many areas, it is difficult to drill and not find water’, says Deming (2002:451) —or a conscious or unconscious response to other cues in the dowser’s surroundings. But, as Deming observes, ‘scientific questions aside, water witching is fascinating as a cultural phenomenon’ (1999:451). Belief in the practice persists to this day, as comments on an online Farmers’ Almanac article attest: We had two witchers as neighbors, saw them many times work their ‘magic’ and never saw them miss. […] [My boss] wouldn’t dig a well with[out] first having it witched. (‘Ron’, online contributor)

Witched my first well in my teens. Twisted the willow branch until it snapped. (‘Mark Dresser’, online contributor)

Closer to home, in 1959 the following account was recorded from a Mr MacGregor in Braemar, Aberdeenshire: I had a boy workin here… and he had a, ye see, this stick, ye know for water divining. […] The stickie started to go, ye know, and— it’s a wonderful thing, that. A wonderful thing, that. How they can get the water like that. Aye. There must be somethin in the blood […] But he was a nice chap, that, too— there was no harm about him, ye know, there was no… Nice chap, too. But it was jist a wee bittie— jist when ye saa it first, ye know, when it started to quiver and then… [go] down, ye know? Ye would

think it was a bittie Auld Nick in him! [laughter] Mr MacGregor shows affection for what he calls ‘the fella with the stick’, and appreciation of his ‘wonderful’ skill, but his slight discomfort at the supernatural aspect of dowsing comes through— there could be a bit of the Devil, or ‘Auld Nick’, at work.

Certainly, water divining sits on the cusp of acceptable and unacceptable paranormal activity. It’s been termed miraculous (by no less a figure than St. Teresa of Ávila), but it’s also been termed diabolical (by another religious dignitary, Martin Luther)— with Besterman reporting various German legends about the Devil or ghostly creatures appearing where dowsers dig (1926:119). The term ‘water witch’ began to be used in the late 18th Century, when dowsing was commonly written about ‘in connection with witches and witchcraft’ (Vogt & Golde, 1958:522). The skill can be seen as innate to the person— as Mr MacGregor put it, ‘something in the blood’ —or tied to the ‘witching rod’ itself, as ‘the representative of the magician’s wand’ (Burne, 1914, 133). Water witches using witching rods— hence, perhaps, ‘Witch Hazel’.

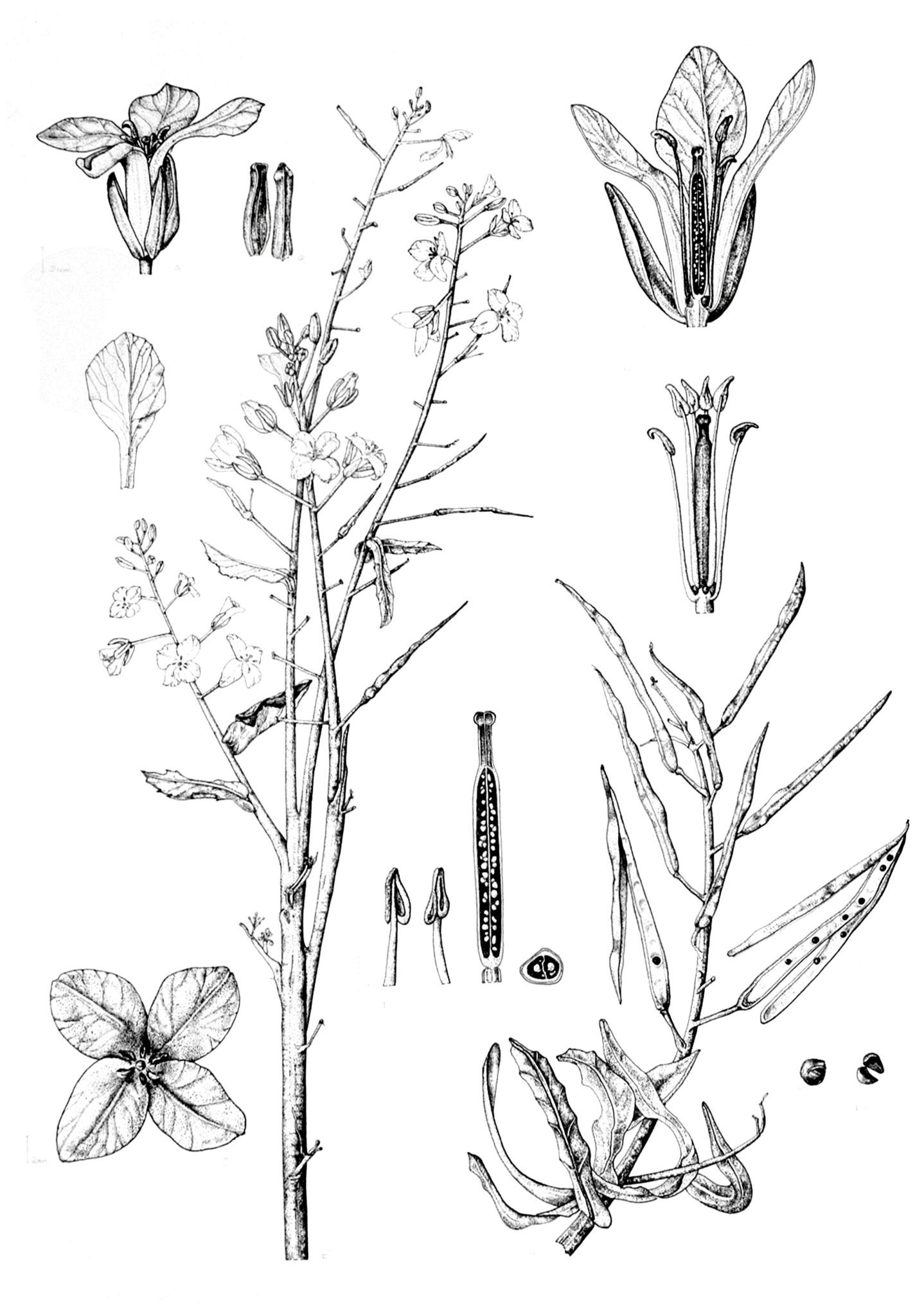

But Witch Hazel is only one of many materials used to fashion witching rods: any springy wood can be used, as can metal and ‘manufactured articles such as tongs, snuffers, or even (be it whispered) a German sausage’ (Besterman 1926:133). As Hamamelis virginiana is native to North America, it was certainly not used on this side of the Atlantic. In Britain it was traditional to use Hazel trees proper, Willow (Salix), various fruit trees, or Wych Elm (Ulmus glabra). In fact, the ‘wych’ in Wych Elm gives an alternative explanation for the ‘witch’ in Witch Hazel. The Old English wiće or wić means weak or bendy, and, according to an etymological dictionary: the suffix ‘wych’ or ‘witch’ has been applied generally or vaguely to various trees having pliant branches. This is an interesting etymological overlap: are witching rods witchy because of their association with arcane knowledge and occult skill, or are they just wych-y— bendy —instead? The homophone allows a perfect folk etymology to emerge, entangling witch and wych to give pliant wood occult undertones that semantically segue into what the wood is used for.

And indeed, ‘Witch Hazel’— or ‘Wych Hazel’— was used to make witching rods in Britain, even if Hamamelis virginiana wasn’t. Since at least 1541, both variants of this name have been used as synonyms for Wych Elm (Ulmus glabra), a tree with its own particularly witchy connotations (Who put Bella in the Wych Elm? is a spooky true crime story well worth looking up). However much we might intellectually accept that trees and shrubs with this suffix are named for the pliant wood they supply, there’s still something witchy about them— and I like them better for it.

References Barrett, L. and Vogt, E. (1969) ‘The Urban American Dowser’, in The Journal of American Folklore, 82 (325):195-213 Besterman, T. (1926) ‘The Folklore of Dowsing’, in Folklore 37 (2):113-133 Burne, C. (1914) Handbook of Folklore, Whitefish, Montana: Kessinger Publishing Co. Deming, D. (2002) ‘Water witching and Dowsing’, in Groundwater 40 (4): 450-452 Johnson, H. (1993 [1973]) The International Book of Trees. London: Mitchell Beazley Kanuckel, A. (2020) ‘Water Witching: Fact or Fake?’ The Farmer’s Almanac, www.farmersalmanac.com/water-witchingdowsing-22011 Vogt, E. and Golde, P. (1958) ‘Some Aspects of the Folklore of Water Witching in the United States’, in The Journal of American Folklore 71 (282): 519-531 Vogt, E. and Hyman, R. (1959) Water Witching U.S.A, Chicago University Press

The interview with Mr MacGregor can be found on the Tobar an Dualchais / Kist o Riches website, the online portal for selected items held in the School of Scottish Studies Sound Archive at the University of Edinburgh: http://tobarandualchais.co.uk/en/fullrecord/37 091

Spring equinox

James Uzzell

The Spring (or Vernal) equinox is a point of balance, when the sun and moon stand still in the sky. It marks the start of the lightest half of the year, and is a time of bonfires and festivities. I think back to my childhood— walking to school as life trickles up through slumberous, frozen surfaces; Imbolc’s hardy Snowdrops (Galanthus nivalis) clearing the glistening cobwebs from the hedgerows; the anticipation of Sweet Violets (Viola odorata) whose delicate perfume will entice early risers from their winter slumbers. In the weeks of awakening leading up to the equinox, it's as if each day is a new opportunity to greet another green bud, watch some smitten songbirds. The youthful energy that pulses through the natural world is enthusiasm, fertility, new growth. So, it's not surprising to see these themes in most cultural celebrations around the world at this time, but particularly in paganism and other nature-based religions.

Before discussing pagan traditions and history, it's important to get a basic understanding of the fluidity of some of the language and names. ‘Paganism’ is most often used as an umbrella term, to describe many different preChristian spiritual practices, typically derived from Celtic, Germanic, and Norse cultures. In reality, paganism is far more complex, with a much broader reach than I can describe here— but there are plenty of great scholars who enjoy the fickle subject of history, if you are inclined to dig deeper. Suffice to say, the spiritual practice most pagans in the UK identify as Celtic paganism is, in fact, neo-paganism— which was ignited around the industrial revolution, when people were forced to renounce their dependence on the land and on natural cycles, and start ‘unwilding’ themselves, becoming ‘civilized’ people who worked in ‘civilized’ factories and cities (Hutton, 2009). The trauma of this left folk hankering back towards history and local folklore, back to those deities it was thought best represented our sacred connection to the wheel of the year, and back to the teachings of our mother earth. Of course, this process was neither universal nor uniform, so modern pagans inherited many names and stories for very similar archetypes. This explains why there are so many practices and paths; Wiccan, Druidry and Norse being the most prominent, each with many paths within them.

The story of the wheel of the year is a tale of the god and the goddess, of life and death. The goddess— mother earth, life-giver, creator of harmony, the divine feminine —gives birth to the Sun (son) on the Winter Solstice, and their divine dance begins. The male form takes many roles throughout the year, as their dance unfolds, but the Spring equinox is a time of courting, of excess energy, of union and wider harmony. As the days lengthen, the return of Father Sun to Mother Earth brings new life and fertility for the coming growing season.

A common alternative name for the Spring equinox is ‘Ostara’, from the Germanic / AngloSaxon festival celebrating the eponymous Maiden of Spring. Many versions of this archetype exist, and Ostara has many names— Ēostre or Ostara in Northumbrian Old English; Ēastre in West Saxon Old English; Ôstara in High German. Personifying the new life and fertility of spring, she is often depicted wearing white, holding flowers and eggs, amongst creatures of the forest— particularly hares. In his 1835 Deutsche Mythologie, Jacob Grimm writes:

This Ostarâ, like the [Anglo-Saxon] Eástre, must in heathen religion have denoted a higher being, whose worship was so firmly rooted, that the Christian teachers tolerated the name, and applied it to one of their own grandest anniversaries. Our Spring maiden is said to sleep all winter, first stirring at Imbolc (on February 1 st), but

rising properly on the equinox, alongside other woodland hibernators. In Druidry, the principal male incarnation at this time is the Green Man— a blooming, energetic forest-being, who brings the sap forth out of the ground, flowers from their bulbs, and urges the lifeforce back into all things. The Green Man is reborn as all life is reborn with him; the Spring Maiden is awake, as the warm sun awakens with her. The equinox is experienced as a time of total balance and unity between the two. From my relationships and creativity, to my ability to channel the magick of the earth, or invoke advice from the gods or nature, this new energy manifests in my life and being.

While it’s the life's work of a few Celtic Reconstructionists to find scripture and history that shed light on ancient rites and rituals, it is accepted that many of these are largely lost to oral tradition. However, one strong theme in pagan practice is that people don't need to follow a rulebook to celebrate the world around them, so neo-pagans of all paths have birthed new traditions and ceremonies over the last century or so.

If, like me, you feel the resurgence of energy beating through everything, resonating on all levels of your being, then you might be moved to celebrate with your own Spring equinox solo ritual. Ede-Weaving (2021) offers some helpful structure, involving: A ritual statement. Draw a circle and set the intention of the ceremony, acknowledging the tell-tale signs of Spring and the environment around you. The Calling of the Goddess— to aid her in Spring's awakening, and to invoke her blessings. The Calling of the God— to manifest his incarnation, and to bring unity to the ceremony. The creation some form of alter— perhaps with two candles, or opposing props —to help materialise the magick of balance and unity. The performance of a rite— this may be walking a labyrinth; writing, then burning the paper; making an offering; or however best you connect with that language of prayer —to help channel your meditation. Giving thanks —acknowledge all parties and thank them for their presence and attention. As it was opened, now close the ceremony.

There are many other rituals that can align us with the earth’s natural transition; watching the rising sun's new dawn; lighting fires to strengthen the energy of the year; or simply planting seeds or bulbs in your garden, giving each one the blessings of Ostara to help grow it to a bountiful Lughnasadh harvest (the first of the three harvest festivals, celebrated on August 1st). We can all find our own ways to resonate with the winking eye of a flaunting robin, the sweet perfumes of the Bluebell wood (Hyacinthoides non-scripta or hispanica). All nature feels this magick, these rituals just help me recognize and acknowledge it, and tune my consciousness to earth-time. As I look forward to the Beltane fire festival on May 1st, I feel excited about my new-born creativity, and where it might lead me between now and the festival of fertility, at the height of spring and the start of summer.

May all your bitter greens sprout big, thick leaves, and— although this past Winter may have been one of the hardest we've all been through —may the sweet sounds of the birds and the bees fill you with at least a little confidence that, even after the longest nights, the sun will rise again.

References Hutton, R. (2009), Blood and Mistletoe, A History of Druids in Britain, Yale University Press: Bristol. Grimm, J. (1835) Deutsche Mythologie, Dieterich: Göttingen. Ede-Weaving, M. Spring Equinox Alban Eilir Solo Ritual: https://druidry.org/resources/spring-equinoxalban-eilir-solo-ritual-no-1(accessed 2021)