4 minute read

Paul Minor

Delving Into Yester~Year

Local historian and writer Paul Miner takes items from The Republican’s Yester-Year column to develop an interesting, informative and often humorous article.

Advertisement

To the Editor: Brownsburg was almost deserted in August 1849 as cholera attacked the populace.

Three had died in seven cases reported.

Doctor Alverson Pinchney Mendenhall, not yet 30 and fearful of contracting the disease, “refused to visit or go near any person that had been near it,” the Locomotive newspaper of Indianapolis reported.

A medical student there, shown how to treat patients and supplied by an Indianapolis physician, “succeeded very well.”

Mendenhall saw the student riding through town, and asking for cholera medicine, left a bottle on the sidewalk and went back into the house while the student filled it, “so fearful was he of contact with the disease.”

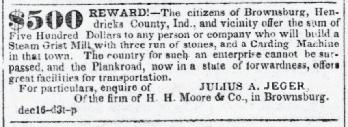

Julius A. Jeger posted an ad in the Indiana State Sentinel in December 1852 alerting readers that Brownsburg wanted to grow. The town offered $500 to anyone who would build a steam gristmill and operate a carding machine.

“The country for such an enterprise cannot be surpassed, and the Plankroad, now in a state of forwardness, offers great facilities for transportation.”

(An 1858 estimate held that land along the Indianapolis and Brownsburg Plank Road had increased in value by $5 an acre.)

Jeger was born in 1808 at St. Croix in the West Indies and educated in Copenhagen, according to The Republican. He came to the States at age 18.

Jeger arrived in the forest around Brownsburg in the spring of 1845 and wrested a farm from that wilderness. He moved to Lizton in 1856 where he farmed and was a merchant.

He lived many years around Brownsburg and Lizton before moving on to Nebraska in 1882 where he ended his days in 1894 among his children.

True to style for those times, a Terre Haute paper vividly described what happened to a worker at the Brownsburg woolen mills when he was caught up by a spinning shaft in February 1869. Discovered half an hour later . . . well, a leg was subsequently found in the dye vat.

Brownsburg’s John South in 1872 learned “it is not safe to remain in the same building with a buzz saw . . . the infernal machine threw a piece of timber at him, which broke his frontal bone into fifteen pieces and tore out an eye.”

Crawfordsville correspondent Perry Winkle declared Brownsburg “has some pretensions to greatness,” in May 1869. The woolen mills might have been a success “but for the want of water.”

Brownsburg, in Perry’s opinion, was “a quiet place, of indefinite size, or small, and though it may receive new life from the railroad, can never be very great.”

White Lick Creek to the town’s west was rather narrow for skating practice in the winter and offered “tolerable accommodations” for summer baptisms.

Reverend Urban Cooper Brewer baptized eight in White Lick Creek in February 1889 during “a blustering snowstorm. The thermometer marked zero. “Several of the enthusiastic converts were young girls.” Tippling was not confined to the male sex in November 1888, according to the shortlived Brownsburg Modern Era newspaper. “It is not only the boys of our town who indulge in the cider-drinking habit . . . We have just learned of some of our young ladies who got their sufficiency more than elegantly filled one night last week with some of the kind that bit.”

Not one saloon was to be found in Hendricks County in 1890, but “intoxicants” were being sold under “Government license” in the towns and villages, “and drunkenness is on the increase. “Great complaint in this regard is made at Brownsburg.” That year’s drought led many to seek the springs feeding White Lick Creek, and in the process, mineral springs on Francis M. Hughes’ 272-acre farm immediately west of Brownsburg and just west of White Lick, were found to hold curative powers. Some claimed to be healed after 10 days of drinking the water.

“In the space of fifty square feet there are six springs, each containing a different kind of water.” On a single July day, invalids “in numbers” visited and drank from the springs, carrying more away in pails and jugs.

Hughes reportedly was having the water analyzed and planned to build a summer resort. Hughes’ farm, if I read maps aright, is long built over by the town.

Paul Miner Lizton

Fashion Dictates Straw Hat Season

Somewhere between the first sign of spring and the dog days of summer, the fashionable man switched from his felt or wool head covering to the cooler, and jauntier, straw hat.

The Republican of March 22, 1888 reported the first straw hats of the season were seen on the streets.

On April 29, 1915, Dr. Huron, president of the town board declared the custom of waiting for a certain time to don straw hats was “a relic of despotism.”

The issue of April 24, 1919 reported John Underwood came out in his straw hat - vintage 1873 - a sure sign that spring had arrived.

The following year, 1920, Osa Dooley donned his straw hat - vintage 1876 - and paraded arount the square mid-February. The Republican reported “on every side and at every turn, he was jeered, hooted, guyed and almost mobbed, but he stuck bravely to his task and finally won out.”

In the advertisement from 1921, shown above, The House of Hadley at Danville, promised the bare headed gentleman could breese in for the cure - a New Straw Lid, all kinds and styles, in a size for every head, for an affordable price of $3.95.