“Just There” Rothko Ryman

Dieter Schwarz

Dieter Schwarz

←

p re f ace

Mark Rothko and Robert Ryman are considered mavericks of postwar American art; their work defnes the course of abstract painting across two generations. So it came as a surprise to discover that these two artists have never before “met” in a two-person exhibition. At f irst appearance, their painterly language may seem opposed, yet each artist’s engagement with natural light and their mastery in distilling the medium to its raw essence unites them. For me, these works are utterly transformational; they call for a pure and intimate engagement with the painted surface that is as direct as it is unknowable. We can turn to Rothko’s understated words to unlock the enduring impact and mystery of their work; he considered painting as “the simple expression of a complex thought.”

It is a true honor to bring these two titans, Mark Rothko and Robert Ryman, together and present their works in direct dialogue for the frst time in this extraordinary exhibition. And, as a gallery with proud Swiss origins, it is particularly signifcant that we have drawn on collections in Switzerland of international standing to loan many of the exemplary works on view, several of which have rarely been exhibited before. These collections are a lasting testament to the enlightened individuals who have been, and remain at, the forefront of the appreciation of contemporary art for more than half a century. We are profoundly grateful for the great generosity that has enabled this project to be realized in our gallery on Bahnhofstrasse in Zurich.

My own encounters with the work of Mark Rothko and Robert Ryman stand out among my formative art memories. With Ursula Hauser and Manuela, we had the opportunity to meet Robert Ryman in his studio in New York in the mid 1990s. A similarly momentous encounter with the paintings of Mark Rothko during an art pilgrimage to the Rothko Chapel in Houston followed. My experience of seeing work by these artists at an

earlier age was made possible by the wonderful Swiss institutions and museums which welcome a wide public to view their programs. Among them were my visits to Hallen für Neue Kunst in Schafausen, which presented dozens of paintings by Ryman, and to the Kunstmuseum in Basel to see the Rothko paintings in the collection displays. Swiss museums continue to introduce future generations to contemporary art of the highest caliber and their visionary foresight is invaluable.

We wish to express our thanks to Dieter Schwarz for his thoughtprovoking curation of “Just There” Rothko Ryman which brings to light intriguing insights into the work of two master artists. We also ofer our dee p est gratitude to Christopher Rothko for his guidance and Adam Greenhalgh and Laili Nasr of the National Gallery of Art for their contribution of knowledge and scholarship. We are very grateful to the numerous institutional and private lenders without whose generosity this exhibition could not have taken place. Our sincere thanks also to our colleagues Sarah Allen, Melisa Arslan, Milena Bürge, Emily Fayet, Olivia Joustra and James Koch for their contributions to this project.

Iwan Wirth, 2025

Mark Rothko, No. 14, 1963

Mark Rothko, Untitled, 1963

→ Mark Rothko, Untitled, 1969

“It’s really difcult to compare one artist’s work with another artist’s work, because there are diferent problems involved, different procedures.

Now, I think you can only compare the work of one artist, I mean one work of his to another work of his.”

—Robert Ryman, 19731

Mark Rothko (1903–1970) and Robert Ryman (1930–2019): this is not the story of a friendship or an acquaintanceship; it is not even a story. It is about the lasting impact of the moment when the younger artist looked at a canvas by the older artist and discovered something that he had never seen before in a painting.

In June 1953, Ryman found work at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, where he was employed in various capacities, but mainly as a security guard in the exhibition and collection galleries. As he paced around the building, he had the chance to study the art on display, and each week he would select diferent paintings to focus on.2 He was especially impressed by Henri Matisse and particularly admired Matisse’s Red Studio (1911): 3 “He could see more than others could see—he managed to get at problems and solve them in a very straightforward and clear way. Then there was his technical mastery, the way he could handle paint. When he worked, there was no fussing around, he was always direct. There was a sureness about what he did—he knew how.”4 The other painter who caught his eye was Mark Rothko, whose No. 10 (1950) was on display in a small room near the end of the collection, along with works by Arshile Gorky, Robert Motherwell, and Richard Pousette-Dart.5 Philip Johnson had acquired Rothko’s No. 10 in 1952 and gifted it to the museum at the request of director Alfred Barr, since the trustees were not in a position to purchase it.6 Ryman was initially not sure what to make of it: “But when I saw this Rothko I thought, ’Wow, what is this? I don’t know what’s going on, but I like it.’ I knew there was something there. What was radical with Rothko, of course, was that there was no reference to any representational infuence. There was the color, the form, the structure, the surface and the light—the nakedness of it, just there.” 7

Rothko’s painting had nothing in common with representational art: “I had been looking at storytelling, subject matter and—well, pictures,” 8 yet it also had nothing to do with the non-representational works that Ryman had already studied in the museum’s collection. In Rothko’s painting, he encountered a form of “non-representationalism” that went even further, given that it was not derived from modernist abstract art, as such. The absence of any kind of motif bowled Ryman over: “This was very

diferent from what I had been looking at. I never read any kind of a representational meaning in his paintings, landscape or whatever. I don’t think he intended that.” 9 However, the complete lack of references of any kind was compensated for by painterly qualities that Ryman carefully

noted for their sheer immediacy—or “nakedness”: “There was color, and there was no frame, and it was very naked, and it was—I liked it immediately, but I didn’t know what was going on.” 10

Ryman’s use of the term “naked” conveys his impression that every aspect of the painting was fully visible, nothing was concealed. Whenever he looked back at that encounter with Rothko’s painting, Ryman generally returned to its distinctive “nakedness”: “There was this very naked canvas with no frame on it and not even a strip, not even tape, you know, just the canvas. I was very impressed by that, by Rothko’s sensibility.” 11 When everything that makes a conventional painting was stripped away, there was no way of understanding a painting: all that was left was one’s sensory experience of it as a phenomenon: “I immediately liked it, I could experience it.” 12

By then, Ryman had already started experimenting with paints, brushes, and canvas: “I was just fnding out how the paint worked, colors, thick and thin, the brushes, surfaces. ” 13 This simple statement already encapsulates what would preoccupy Ryman throughout his entire career as a painter. A decade later, when he had his frst opportunity to publish a text about his work (as a participant in a group exhibition), with the term “naked” he implicitly alluded to his Rothko experience: “The paint must be isolated on the space, surrounded by areas of emptiness, so the paint itself becomes as naked as the space. ” 14 For Ryman, painting—that is to say, mark-making using paint—was thus also about taking something away from the canvas. Adding to the painting involved erasing something else to preserve the presence of the pictorial space and of the paint, not as voids, but in their nakedness: “Generally the approach was to keep everything as naked and as immediate as I could.” 15

The two painters only came face to face once, in 1958. It so happened that Ryman, Rothko, and the latter’s friend, painter William Scharf, found themselves at the same table in the restaurant at the Museum of Modern Art, where Rothko occasionally dropped in.16 However, there was not any real conversation between them: “I was very shy, and I didn’t feel like I was a painter at all yet and so, how could I talk to him?” 17 Maybe it was just as well that Ryman did not introduce himself as a painter; the curator Katharine Kuh once quoted a comment by Rothko, which suggested he did

not enjoy meeting younger artists: “When young painters come to me and praise my work, I am certain that they are really assaulting me. Beneath their praise I feel their envy and jealousy . . . by praising me, they actually try to destroy my infuence over them.” 18

In 1959, a second painting by Rothko arrived in the collection at the Museum of Modern Art,19 yet Ryman never mentioned it, nor did he discuss Rothko’s exhibition at the Sidney Janis Gallery a year earlier, which presumably he would have visited. And he only spoke in passing of Rothko’s retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art in 1961,20 although Lucy Lippard, who would shortly marry Ryman, recalled an enthusiastic response to the exhibition from him: “The Rothko show was a big deal for us, because Rothko . . . Bob was mad for Rothko’s work.” 21 The paintings were hung close together, not just because of a lack of space but because Rothko wanted to avoid them being presented as decorative objects. As he wrote to Kuh in 1954 in connection with his exhibition at the Art Institute of Chicago, the rooms were to be “saturated” with paintings to underline the intensity of the work. Viewers would thus experience the paintings close-up and immediately be drawn into them: “This may well give the key to the observer of the ideal relationship between himself and the rest of the pictures.” 22

While Rothko was working on his murals for the Four Seasons restaurant in the Seagram Building, he was also intensely preoccupied with painting in oils on watercolor paper.23 Between 1958 and 1960, he created over ffty of these paintings, which were then mounted on wood panels and, like the oils on canvas, displayed without frames. The structure of the oils on paper echoes the structures of the canvases: usually there would be three thickly painted felds of diferent sizes, with “ragged” edges, on a ground prepared with an almost transparent watercolor wash. The multiple coats of thinned oil paints soaked into the paper, creating a colorsaturated, strikingly luminous matte surface, particularly in the paintings with felds in vermilion, yellow, and orange. Unlike the monumental Seagram oils on canvas, in darker hues, which were often in a horizontal format, the works on paper are in medium-sized formats and vertical, like Rothko’s earlier paintings, inviting comparison between their proportions

Installation view of the exhibition, Mark Rothko Museum of Modern Art, New York January 18 – March 12, 1961

and those of the human upper body. Rather than exhibiting these more intimate works, Rothko hung them in his studio and in his apartment, where they only became known to a smaller circle of friends and acquaintances. It was not until 1968 that he returned to painting on paper, initially in oils but then exclusively in acrylics and in increasingly large formats that had a greater afnity with the oils on canvas.

Evidently Ryman was not distracted by the drama that Rothko attributed to his paintings with references to classical tragedy; Rothko’s sole interest was in “expressing basic human emotions—tragedy, ecstasy, doom, and so on,” as he put it to the writer Selden Rodman.24 He also

emphatically distanced himself from any kind of abstract painting. When he frst encountered a painting by Rothko, Ryman could not have known that his unprejudiced gaze had in efect fulflled Rothko’s hopes for his work: “A picture lives by companionship, expanding and quickening in the eyes of the sensitive observer.” 25 But above all, it was what Ryman saw thanks to his physical proximity to the painting—as he scrutinized every detail—that he still remembered decades later: “The deep edges of the painting went back toward the wall, and the paint went around the side. You could see staples, it was so open. ” 26 Ryman’s observation was correct, as the description given by the conservator Carol Mancusi-Ungaro confrms: “Rothko’s insistence on the importance of the painted edge may be seen as early as 1950 in No. 10, for which the artist did not have fabric wide enough to cover the sides of the strainer completely: he carefully stapled one selvage of the fabric to the right side, secured the remainder to the left, then painted the exposed wood where necessary.” 27

In response to the question as to the correct distance from which to view his paintings, Rothko once provocatively replied, “eighteen inches.” 28 Clearly, it is impossible to take in the whole composition from that distance; instead, the viewer would be confronted with one particular part of it. Yet that distance would allow viewers to see the surface of the paint, the way it was applied, and the texture of the brushstrokes before their gaze started to move up and down, taking in all the diferent parts of the painting. During that process, the composition and any internal connections recede; in that respect, too, Ryman’s gaze suited Rothko’s approach and his insistence—highlighting the unchanging, symmetrical structure of his paintings—that he was “not interested in relationships of color or form or anything else.” 29

Some viewers might be provoked by that statement. However, when critic Robert Goldwater reviewed Rothko’s exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, he picked up on exactly that issue and pointed out to his readers that Rothko had reduced his compositions “to the unique colored surface which represents nothing and suggests nothing else,” moreover, “[Rothko] has handled his color so that one must pay ever closer attention to it, examine the unexpectedly joined hues, the slight, and continually

slighter, modulations within the large area of any single surface, and the softness and the sequence of the colored shapes. ” 30

Given that these compositions were not about internal pictorial relationships, something else had to take center stage. Ryman’s paintings could not properly be described as formal compositions: they do not rely on interconnected motifs and elements or on the interactions of diferent colors. On the contrary, the paintings in his General series (1970) consist of a centrally placed, even surface made up of several layers of gloss enamel, which could be described as a kind of non-form, since there is nothing in it for the eye to cling to apart from where it meets the loosely applied Enamelac ground that is exposed on all edges of the canvas. In Untitled (1973), the matte enamel is not applied to a fabric support but rather to an aluminum panel, which is visible at the left and lower edges. Light refects from the paint and the metal in a way very diferent from the General paintings; the paint’s irregular edge accentuates this contrast. In another untitled painting of the same year, the paint is drawn in regular brushstrokes from left to right across the aluminum panel, so the starting point near the left edge sets an accent. In Core (1983), thinly applied vertical stripes at the left and right edges are separated from the evenly painted central feld and the panel’s edges by very narrow unpainted areas. All these elements are set beyond the painting’s fxtures (or fasteners, to use the artist’s preferred term), serving to complexify and enhance what may initially seem a simple composition. Thus, the viewer’s gaze glides from the central, painted surface to seemingly secondary planes and returns from there to the painted area. Meanwhile, Dominion (1979), with its impasto paint application, is the polar opposite to Core, yet the painted area does not provide a greater degree of formal structure that helps the viewer to understand the work as a whole. The main focus of the painting is on the fne texture of the picture plane, which can only properly be appreciated from close-up. The painting does not follow any predetermined order; on the contrary, it simply spreads out on the canvas, randomly yet resolutely, in one continuous movement that captivates the viewer.

The artist’s intention here is to invite a form of close scrutiny (not an overview) that enables the viewer to engage fully with the painterly treat-

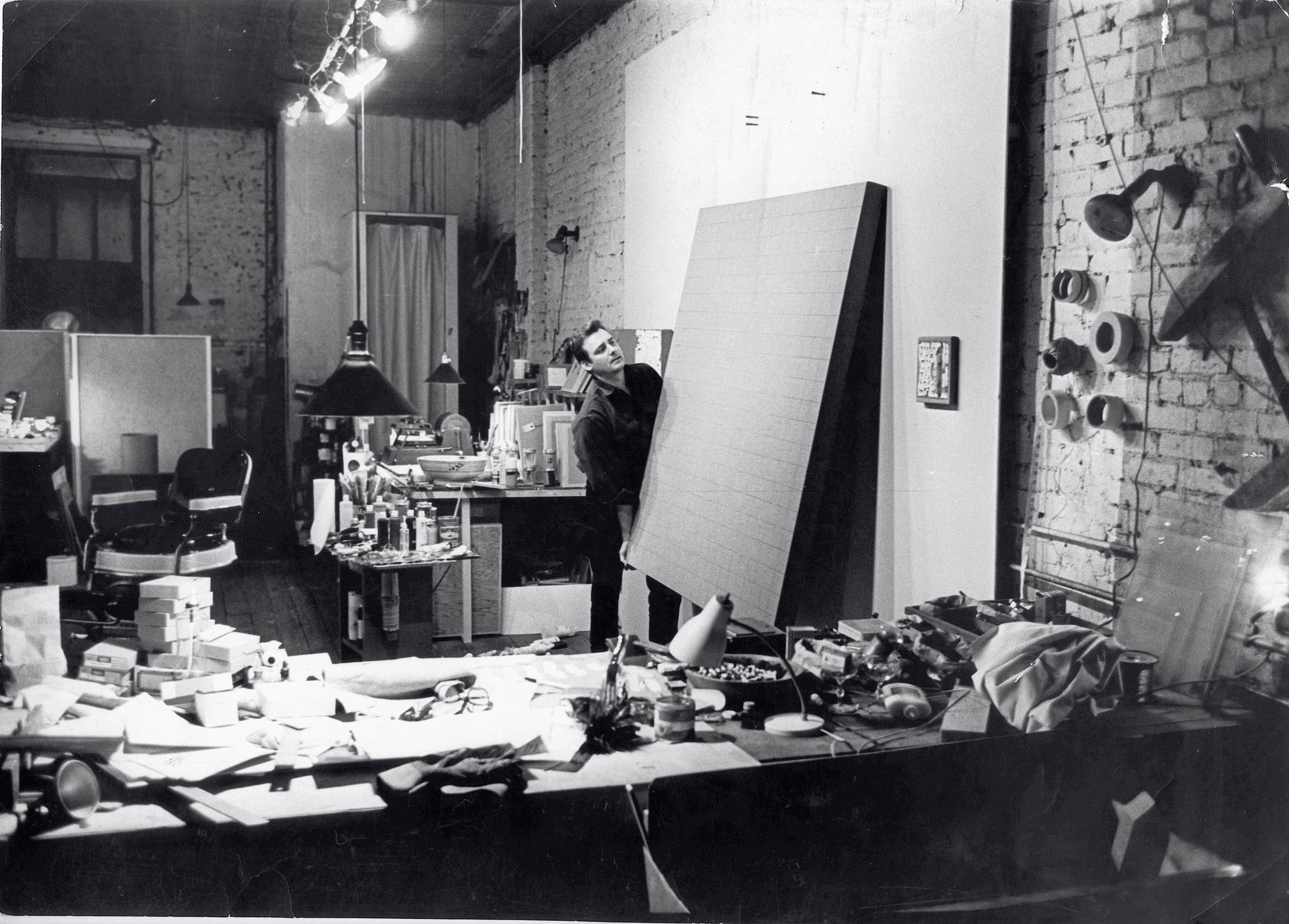

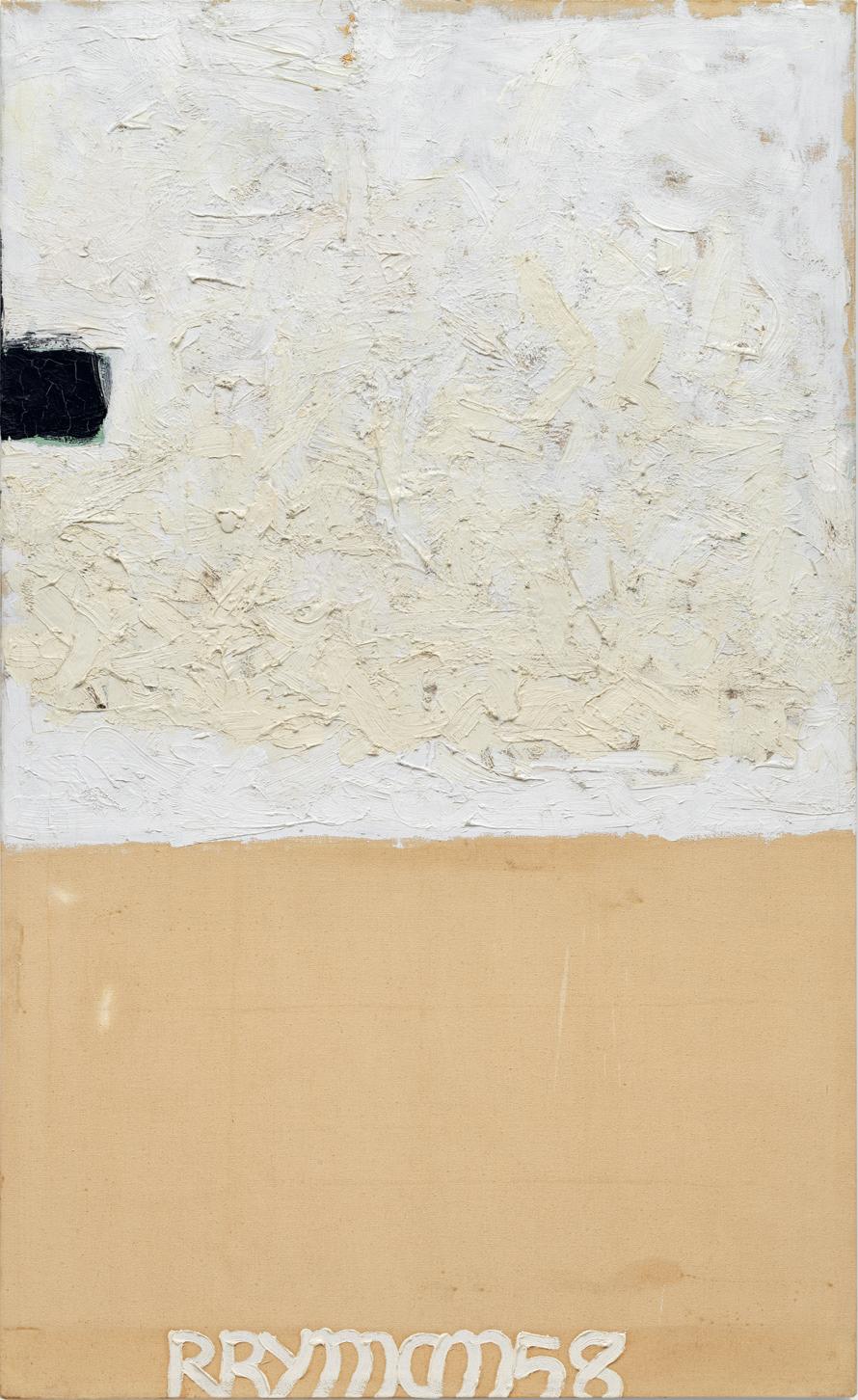

Ryman, Untitled, 1958

ment of the surface of the work. During the course of the 1950s, Ryman’s use of brush and paint allowed him to eliminate the eclecticism of his early paintings and to clarify the parameters of his own processes. As a rule, his work never approaches too closely to that of Rothko, the only signifcant

exception being the composition of his vertical Untitled (1958). If anything, this painting confrms a remark he once made: “Sometimes you can just pick up a little thing from looking at something and hardly realize where you saw that or how it came to you.” 31 But Ryman also undermines any supposed allusions to Rothko’s pictorial format one by one: by painting the feld as a square that reaches right to the edge of the picture; by disrupting the coherence of the feld with a black shape (also found in other paintings of the late 1950s); and ultimately by using the signature and date line to demarcate the lower edge of the work. Rotating this painting ninety degrees clockwise, as it were, leads to Untitled (1959), in which Ryman retains the basic composition but alters some aspects of it: the square feld now occupies more of the picture plane; the contrast to the remaining left area is softened by it being painted in white (albeit not impasto); and the signature has been moved from an edge into the main feld, so it looks almost casual. From this work onward, the vast majority of Ryman’s pictorial decisions were located within his chosen square format, which cannot be read as analogous to windows or human fgures.

This takes us back to Rothko, in the sense that Ryman had learned from him not to treat a painting as a bearer of meaning but rather as an object in its own right: “I might have got something else from him. His way of handling the problems of—well, not color, but his use of the painting as an object in itself. ” 32 Rothko made it clear that his own paintings had that material presence when he explained the diference between his work and that of Ad Reinhardt, who he referred to as a “mystic.” He suggested that Reinhardt’s paintings were immaterial, as opposed to his own, which were there “materially. The surfaces, the work of the brush and so on. His are untouchable.” 33 This was a pivotal lesson for Ryman; he was not moved by Rothko’s atmospheric colors that so impressed many of his contemporaries. When everything had been eliminated that was not intrinsic to painting, all that was left was paint and the task of engaging with the paint and the picture carrier as an object. Ryman was very clear about his intentions: “I wanted to paint the paint.” 34 In the same vein as Rothko’s work, Ryman’s paintings do not depict light: they are objects on a wall in real light, and their appearance is dependent on that.35 The

notion of paint as an object and of the painting as an object is not at all afected by whether the paint appears smooth (as in the General paintings) or thick (as in King, 1998), or whether the painting lies fat against the wall (as in Summary, 1988) or whether it is attached to the wall by fxtures (as in the case of Core and Dominion). In the work of both Rothko and Ryman, the viewer can see “the way [the painting] projected of of the wall and the way it worked with the wall plane.” 36 When paint is painted as paint, the crux is not the “purity” of painting; it is not about limitation or accumulation. On the contrary, this process opens up endless ways for a painter to shake of preexisting notions and to show something that has never been seen before—even in an entirely romantic sense, of the kind Ryman detected in Rothko’s work: “He was working with color, very much with color, and with the object, the painting. His work might have a similarity with mine in the sense that they may be both kind of romantic, if you want it, I mean, in the sense that Rothko is not a mathematician, his work has very much to do with feeling, and sensitivity.” 37

Much can be written about what people have said about Rothko’s work and what he himself said about it. But let us not forget that Ryman, who started out simply by looking at Rothko’s painting in the Museum of Modern Art and never lost that focus, perceived things that cannot be put into words; because what is seen does not manifest itself in any other way, it appears directly, wordlessly, yet necessarily and inevitably in one’s feld of vision. How should one respond to that? By painting. In a lecture at an art school in Maine, Ryman later referred to Rothko in his own unpretentious account of the experience of seeing that painting: “I couldn’t see it. Then, I did see it. Then I learned to see what he was seeing and working on. ” 38

1 Robert Ryman [1973], in Achille Bonito Oliva, Dialoghi d’artista: Incontri con l’arte contemporanea 1970–1984 (Milan, Italy: Electa, 1984), 89.

2 Interview with Robert Ryman by Paul Cummings for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, October 13, 1972.

3 “I know he [Alfred Barr] asked me once—which I don’t know why he did this, but he asked me if I preferred the Matisse Blue Window [1913] to the Matisse Red Studio, which I preferred. And I said, ‘Well, it’s very difcult,’ I said, ‘I like both, but maybe I would go for the Red Studio.’ And he didn’t say anything, he just kind of nodded.” Robert Ryman in “David Hofman MoMA History Interviews,” 1983.

4 Robert Ryman, in Grace Glueck, “The 20th-Century Artists Most Admired by Other Artists,” Art News, 76, no. 9 (November 1977): 99.

5 Robert Ryman, interview with Robert Storr for the Museum of Modern Art Oral History Program, 2003.

6 No. 10 (1950), oil on canvas, 901 4 × 57⅝ inches (229.2 × 146.4 cm), Museum of Modern Art, New York, Gift of Philip C. Johnson. See David Anfam, Mark Rothko: The Works on Canvas. Catalogue Raisonné (New Haven and London: Yale University Press; Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art, 1999), no. 449. From March 1955 to August 1956, this painting was on tour with the survey exhibition Modern Art in the U.S.A.; it was loaned again from April 1958 to September 1959 for the touring exhibition The New American Painting. It seems fair to assume that Ryman would have seen it before March 1955, when it was frst shown at the museum.

7 Robert Ryman, in Nancy Grimes, “White Magic,” Art News 85, no. 6 (Summer 1986): 89.

8 Interview: Kate Horsfeld with Robert Ryman [video tape] (Chicago: Video Data Bank, School of the Art Institute of Chicago, 1979).

9 “Robert Ryman: Interview with Robert Storr on October 17, 1986,” in Abstrakte Malerei aus Amerika und Europa, ed. Galerie nächst St. Stephan Rosemarie Schwarzwälder (Vienna and Klagenfurt, Austria: Ritter Verlag, 1988), 214.

10 Interview: Kate Horsfeld with Robert Ryman [video] (see note 8).

11 Interview with Robert Ryman by Paul Cummings (see note 2).

12

Robert Ryman, in Inside the Art World: Conversations with Barbaralee Diamonstein (New York: Rizzoli International Publications, 1994), 213.

13 Robert Ryman in Nancy Grimes, “White Magic” (see note 7): 89.

14 Robert Ryman, in Art ’65: Lesser Known and Unknown Painters—East to West, exh. cat. (New York: American Express Company, 1965), 60. See Ryman’s later use of the term, in Dieter Schwarz, “The Nakedness of Paint and Space: Robert Ryman: 1961–1964,” in Robert Ryman: Early and Late (New York: David Zwirner Books, 2024), 16–18.

15 David Carrier, “Robert Ryman on the Origins of His Art,” Burlington Magazine 139, no. 1134 (September 1997): 631.

16 The topic of conversation indicates that the meeting may have taken place after the fre that broke out at the Museum of Modern Art on April 15, 1958: “He [Rothko] was talking about fre. He was concerned that, if his studio burned down, that he would lose all of his paintings, and how it would be nice to have a freproof studio, or something to that efect.” Robert Ryman, Museum of Modern Art Oral History Program, 2003 (see note 5), 7.

17 Ibid.

18 Katharine Kuh, My Love Afair with Modern Art: Behind the Scenes with a Legendary Curator, ed. and completed by Avis Berman (New York: Arcade Publishing, 2006), 145.

19 No. 16 (Red, Brown and Black), 1958, oil on canvas, 106⅝ × 117⅜ inches (270.8 × 297.9 cm), Museum of Modern Art, New York, Mrs. Simon Guggenheim Fund. See David Anfam, Mark Rothko (see note 6), no. 624.

20 “I remember seeing the Rothko show, which was kind of a small show, actually. It was on the frst foor. It wasn’t a big show.” Robert Ryman, Museum of Modern Art Oral History Program, 2003 (see note 5), 15. In fact, the exhibition included ffty-four works; see Peter Selz, Mark Rothko, exh. cat. (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1961), 43–44.

21 Lucy Lippard, interview with Sharon Zane for the Museum of Modern Art Oral History Program, December 21, 1999.

22 Mark Rothko, “Letter to Katharine Kuh, September 25, 1954,” in Mark Rothko, Writings on Art, ed. Miguel López-Remiro (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2006), 100.

23 For a detailed account of this, see Adam Greenhalgh, Mark Rothko: Paintings on Paper, exh. cat. (Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art; New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2023).

24 Selden Rodman, Conversations with Artists. Introduction by Alexander Eliot (New York: Devin-Adair Co., 1957), 93.

25 Mark Rothko, “The Ides of Art: The Attitudes of Ten Artists on Their Art and Contemporaneousness” [1947], in Mark Rothko, Writings on Art (see note 22), 57.

26 “Robert Ryman: Interview by Jefrey Weiss, 8 May 1997,” in Jefrey Weiss, Mark Rothko, exh. cat. (Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art, 1998), 367.

27 Carol Mancusi-Ungaro, “Material and Immaterial Surface: The Paintings of Rothko,” ibid., 290–91.

28 Teresa Hensick and Paul M. Whitmore, “Rothko’s Harvard Murals,” in Mark Rothko’s Harvard Murals (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Center for Conservation and Technical Studies, Harvard University Art Museums, 1988), 15.

29 Mark Rothko, in Selden Rodman, Conversations with Artists (see note 24), 93.

30 Robert Goldwater, “Refections on the Rothko Exhibition,” Arts 35, no. 6 (March 1961): 43–44.

31 Robert Ryman, in Barbaralee Diamonstein, Inside New York’s Art World (New York: Rizzoli International Publications, 1979), 339.

32 Robert Ryman, in Grace Glueck, “The 20th-Century Artists Most Admired by Other Artists” (see note 4): 99–100.

33 Mark Rothko, quoted in Dore Ashton, About Rothko (New York: Oxford University Press, 1983), 179.

34 Robert Ryman, in Barbaralee Diamonstein, Inside New York’s Art World (see note 31), 332.

35 “The painting deals with real surfaces and real light, real structure.” “Robert Ryman: Interview by Jefrey Weiss, 8 May 1997” (see note 26), 368.

36 Ibid., 369.

37 Robert Ryman, in Achille Bonito Oliva, Dialoghi d’artista (see note 1), 93.

38 Robert Ryman, “Lecture,” 1976. Archives of Skowhegan School of Painting & Sculpture, Skowhegan, Maine.

Robert Ryman, Untitled, 1959

Robert Ryman, Untitled, 1973

Robert Ryman, Untitled, 1973

Robert Ryman, Dominion, 1979

Robert Ryman, Core, 1983

Robert Ryman, Summary, 1988

Robert Ryman, King, 1998

Mark Rothko:

Untitled, 1958

Oil on paper, laid down on canvas

29 7 8 × 22 inches / 76 × 56 cm

Private Collection, Switzerland

Untitled, 1959

Oil on paper, laid down on board

29 3 4 × 21 1 4 inches / 75.5 × 54 cm

Private Collection

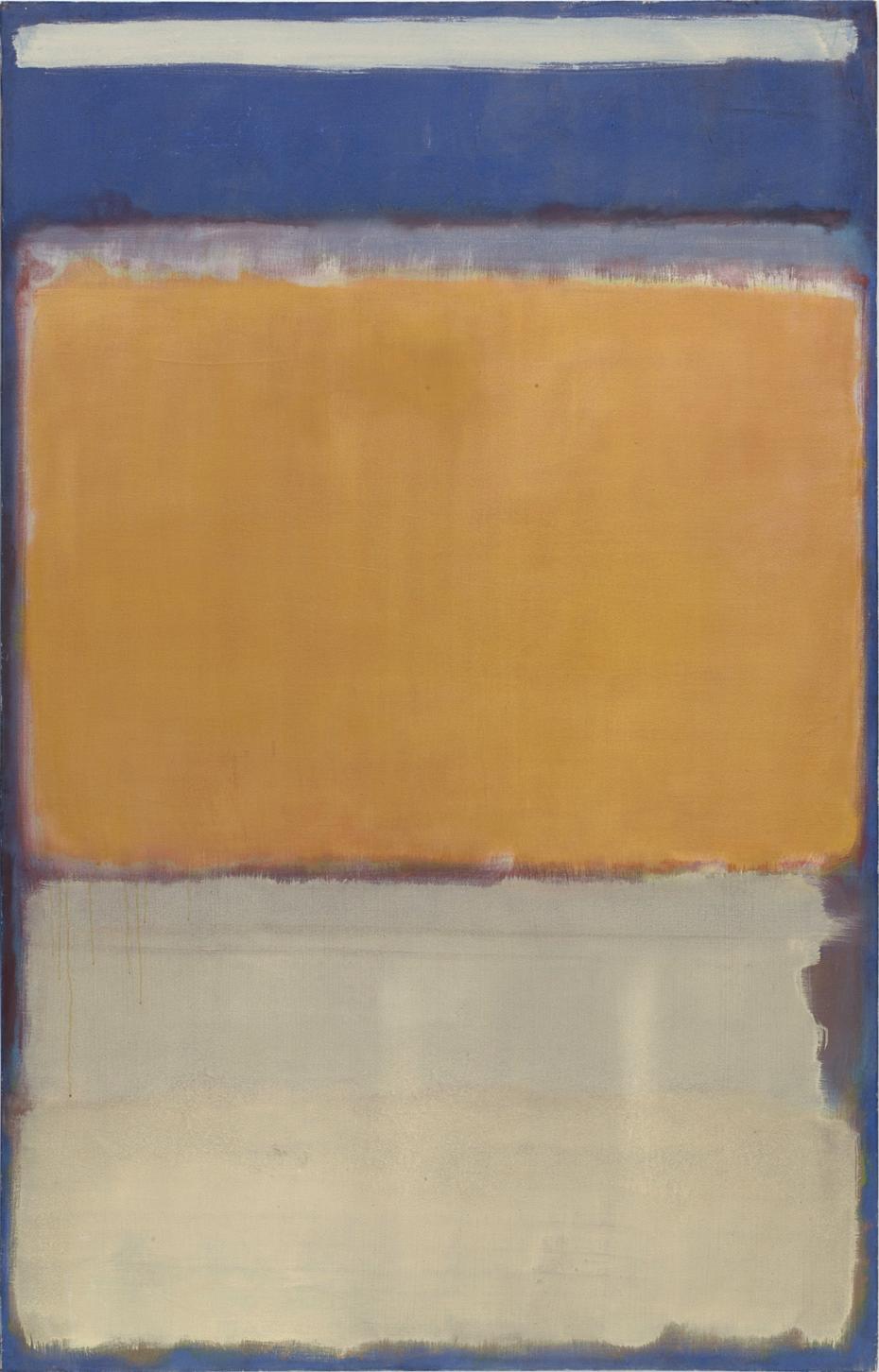

No. 14, 1963

Oil on cotton duck canvas

69 1 4 × 50 inches / 176 × 127 cm

Collection of Siegfried and Jutta Weishaupt

Untitled, 1963

Oil on paper, laid down on canvas

29 5 8 × 21 3 4 inches / 75.4 × 55.1 cm

Private Collection

Untitled, 1969

Acrylic on paper, laid down on canvas

85 7 8 × 60 3 8 inches / 218.1 × 153.5 cm

Private Collection

Robert Ryman:

Untitled, 1959

Oil on primed stretched cotton canvas

33 3 4 × 45 ⅛ inches / 85.7 × 114.6 cm

Private Collection, courtesy Anthony Meier, Mill Valley, California

Untitled, 1963

Oil and conté on sized unstretched linen canvas

Approx. 8 1 4 × 8 1 4 inches / 21 × 21 cm

Private Collection, Switzerland

General 52" × 52", 1970

Enamel and Enamelac on stretched cotton canvas

52 × 52 inches / 132.1 × 132.1 cm

Private Collection, Germany

Untitled, 1973

Enamel on aluminum panel

37 × 37 inches / 94 × 94 cm

Private Collection, Switzerland

Untitled, 1973

Enamel on aluminum panel

39 3 8 × 39 3 8 inches / 100 × 100 cm

CREX Art Collection

Dominion, 1979

Oil on stretched cotton canvas, with four fasteners and four square bolts

canvas: 72 × 72 inches / 183 × 183 cm

overall: 75 1 4 × 72 inches / 191 × 183 cm

Private Collection, Switzerland

Core, 1983

Oil and gesso on fberglass-aluminum

honeycomb panel with redwood edge, with two aluminum fasteners and four cadmium-plated square bolts

panel: 46 × 46 inches / 116.8 × 116.8 cm

overall: 50 ⅛ × 46 inches / 127.3 × 116.8 cm

Private Collection, Switzerland

Summary, 1988

Lascaux acrylic on Gatorboard

26 × 26 inches / 66 × 66 cm

Private Collection, Switzerland

King, 1998

Oil on archival board, mounted on medium density fberboard

7 ⅝ × 7 3 4 inches / 19.4 × 19.7 cm

Private Collection, Switzerland

This catalogue is published on the occasion of the exhibition

“Just There”

Rothko Ryman

12 June to 13 September 2025

Hauser & Wirth Zurich, Bahnhofstrasse

Curator of the exhibition

Dieter Schwarz catalogue

Editor

Dieter Schwarz

Translation from German Fiona Elliott

Editing

Julia Monks

Editorial support

Emily Fayet

Design

Silke Fahnert, Uwe Koch

Lithography

Gundula Seraphin, Bad Munstereifel

Production

DZA Druckerei zu Altenburg GmbH

“Just There”

Rothko Ryman

© 2025 Hauser & Wirth www.hauserwirth.com

Text: © the author

For the illustrated works: All works by Mark Rothko © 1998 Kate Rothko Prizel & Christopher Rothko / 2023, ProLitteris, Zurich PVDE / Bridgeman Images All works by Robert Ryman © Robert Ryman / 2025, ProLitteris, Zurich

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval systems) without permission in writing from the publishers.

Photo credits

Liberman Photography Archive, Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles © J. Paul Getty Trust: p. 4; unpublished photo by New York Times: p. 5; Digital image, The Museum of Modern Art, New York/Scala, Florence: pp. 16, 19; Jon Etter: p. 9, 29; Stefan Altenburger Photography Zürich: pp. 2, 8, 11 – 13, 22, 31 – 37.

Printed and bound in Germany

Hauser & Wirth

Bahnhofstrasse 1

CH–8001 Zurich

Hauser & Wirth