5 minute read

Q&A: Richard Pyatt – With Gratitude

Q & A

Richard Pyatt – With Gratitude Richard Pyatt, teacher, Head of English (1996-2006; 2009-2013), President of the Common Room (2000-2003; 2015-2017), much loved colleague and friend, retires this summer after 32 years at

Advertisement

Westminster. Here, with the present Head of English, Abigail Farr, he reflects on his time at the School.

Richard, can you describe yourself as you were when you first arrived at Westminster?

Westminster felt very much like being back at Oxford, but on better terms – a very exciting college, and in London! Having spent my early adult life in Oxford, then commuting to High Wycombe for my first teaching job, I was thrilled finally to have made it to the capital. I shared a big basement flat with friends in Clapham South and I quickly got to know everyone in the School community. It was like one big academic party. After my first Election Dinner in 1988 I was bombarded with holiday invitations. I was full of the buzz all the time.

What was the English department like in those days?

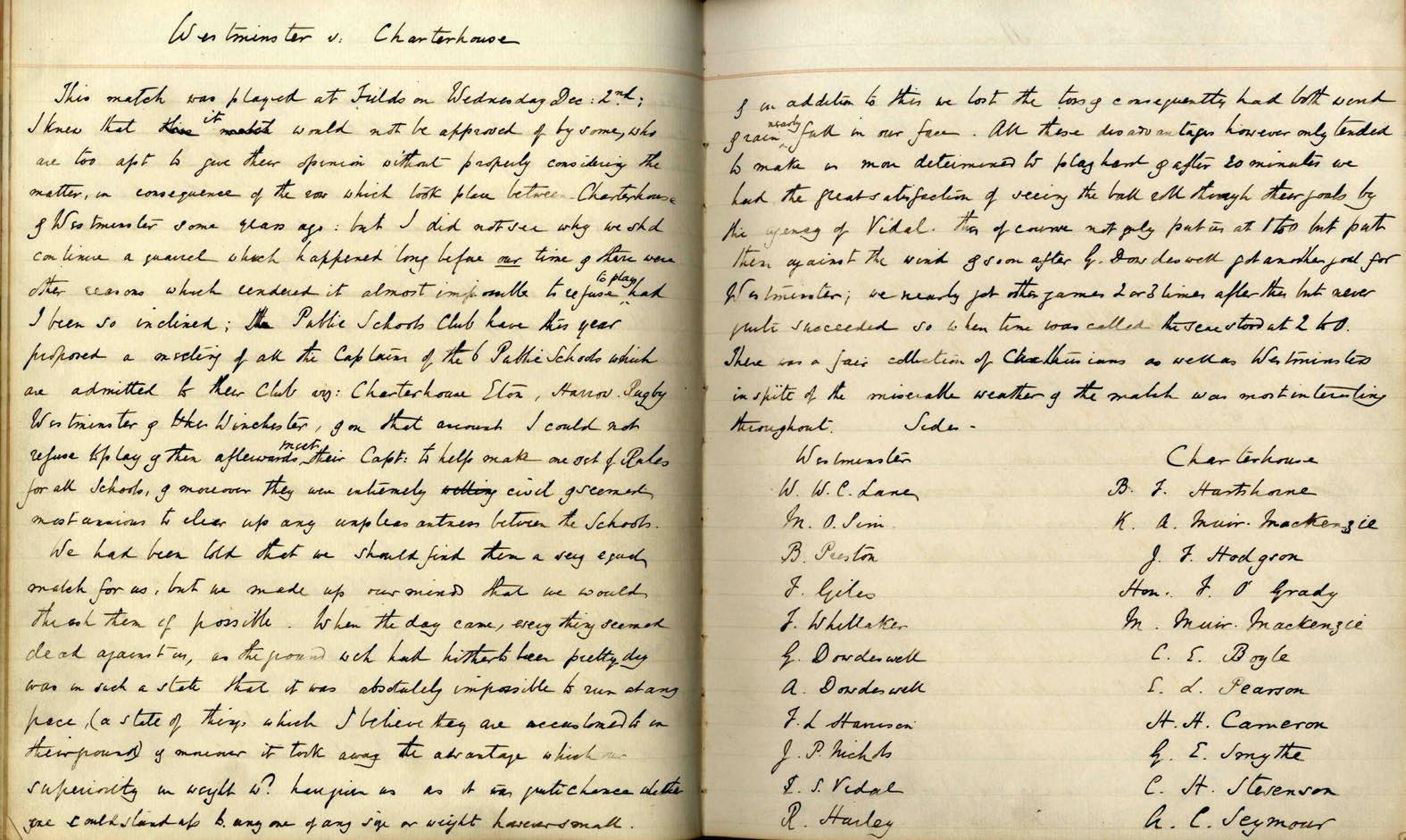

Some teachers had been there since the 1960s. I was interviewed by David Edwards (Westminster 1975-2016). When I said I liked poems because they fitted conveniently into a single lesson, he replied, “What about Paradise Lost?” We spent a good part of the interview chuckling. I was appointed with Michael Mulligan and Charlotte Moore; we quickly became pals. Gavin Griffiths also remains a great chum – brilliant, mischievous and probably pretty suspicious about the new bugs who were all younger than him. We were helped by having the Head Master, David Summerscale, in the department; a huge literary enthusiast and a great support to me when I became head of English in 1996. The department indulged in great debates and arguments over authors, texts, critical schools and ideologies. Sometimes these could become heated. I can remember, at different times, keys being thrown at a dissenting colleague during a meeting and at another time a banana. I chaired one such debate between John Field, a Westminster legend in his own right who argued for a more traditional approach to literature, and the young firebrand Michael Mulligan who was probably more of a Marxist poststructuralist. Usually our discussions would spill out into pubs that no longer exist, like The Old Rose and The Paviours. We lived and breathed literature and the pupils were huge contributors to and participants to that culture, as they are today.

What have you most enjoyed teaching?

The freedom and opportunity to work with such a wide variety of texts and authors over the years has been wonderful. When you teach the work of an author it often seems as though he or she is present in the room. Larkin has remained with me throughout the years. Hardy, Dickens – especially Great Expectations: I can see Pip in my younger self, and, perhaps now, the Mayor of Casterbridge! The Tempest was very much a touchstone and the Romantic poets; King Lear stumbled through hundreds of lessons and Hamlet has died many times. Novels could burn brightly and then not make an appearance again for decades, such as Muriel Spark’s, The Girls of Slender Means. I had to stop teaching Persuasion because my copy crumbled away – and I have always loved ‘going in with a poem’.

Is there anything that didn’t work?

I now realise that dear Iris Murdoch’s great novel The Sea is a retirement text and not for adolescents, and a few groups followed me into the pages of Sir Walter Scott. Sometimes I ‘pitched’ lessons wrongly, but they were great fun and could be anarchic. With some groups I couldn’t put a foot wrong and others dug their heels in. I taught the present Housemaster of Dryden’s, Tom Edlin, back in the early nineties and he can remember far too many of my lessons. Apparently, our principal text was Northanger Abbey and when I was bored with the class I would send them out onto a dangerous balcony to gather inspiration for their haiku compositions.

Where else did you hold your classes?

All over the place. We were peripatetic until the School acquired the Weston Building for Humanities classrooms in the Millennium. That made a huge difference. But, until then, we had lots and lots of lessons in the Library, which meant reading and books were right at the centre of Westminster life. Classrooms back in 1986 were ingeniously tucked into holes and warrens all around Yard – the crowded piazza where everything happened. Houses were independent fiefdoms with their own traditions and characteristics. I usually dined in Liddell’s and felt part of a wacky and affectionate family in that House.

What would you say you found most surprising at Westminster?

Westminster helped put right a wrong from my childhood by showing me that sport need not be associated with fear. Thanks to Danny Gill, the open-minded Head of Station when I arrived, anyone in sporting accolades could have a bit of a go and join in. I took over Badminton in 1994 and it became my sport until my elbows and knees went last year – a direct result of so many hours on the court!

What about Expeditions?

This was another missing piece from my childhood. I got into the culture of Expeditions at Westminster having had no background in it, at first to please my new friends on the Westminster staff. Shortly after arriving at the School I led an expedition to Hadrian’s Wall and I fell in love with it. The School bought a house near Alston shortly after, which I must have visited over thirty times, not only with School groups but with friends in the holidays. I even took my parents up there. It is thrilling to be so near Hadrian’s Wall. I have many happy memories of France, too. Maurice Lynn and I took Expeditions to Gignac and Agde where he also had second homes. Maurice would drive all night and we would wake up next to the Mediterranean. I would love to see Westminster acquire a good European base, especially post-Brexit, so that pupils can experience this again on a regular basis.

Any other wishes for the Westminsters of the future?

We should teach them all to cook! Bring back Domestic Science! Cooking restores your inner balance. It’s good for people, physically and mentally and these days is linked to awareness about health, food production and the environment. Regardless of that, let’s put creativity and the imagination at the heart of everything we do. ■

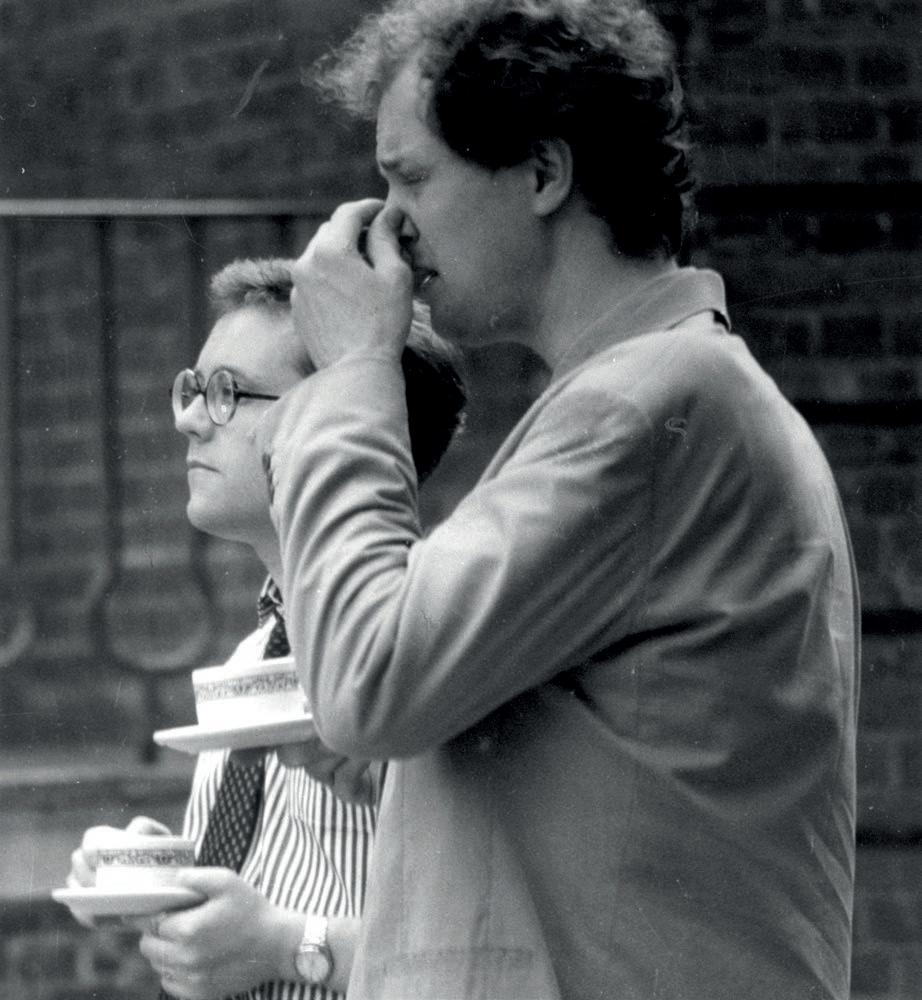

Richard Pyatt with Michael Davies