12 minute read

Westminster and the Royal Navy in the 18th and 19th Centuries

Dr Michael Willoughby (KS, 1948-53)

wo hundred years separated the careers of the two OW admirals, George Legge and Richard Phillimore, featured in The Elizabethan’s summer issue of 1953. In that interval the School supplied the Navy with many other officers, of whom a good proportion became admirals, though others who would have expected to achieve high rank were prevented from doing so by disasters that overtook them in the earlier years of their service. In the account that follows it will be noted that most were scions of noble families. They entered the School at what would now be considered prep school age, remained there in most cases for one to three years, and then joined the Navy in their early teens, either directly as deckhands or via the Royal Naval Academy at Portsmouth.

Advertisement

OW admirals frequently come out as ‘characters’. The earliest of those now considered, Edward Vernon (b. 1684), is widely known for his introduction of the daily ration of ‘grog’ (rum diluted

Edward Vernon (b. 1684) is widely known for his introduction of the daily ration of ‘grog’ (rum diluted with water) for every junior rating.

Edward Vernon

with water) for every junior rating. This term derives from Vernon’s coat of grogram, a coarse fabric of silk, of mohair and wool, or of these mixed with silk, often stiffened with gum (OED), and it has remained his nickname ever since. The measure was intended to minimise the drunkenness at sea that had been a major handicap to the Navy’s performance – and it succeeded brilliantly. Vernon differed from most OW sailors in being an intellectual, having excelled in the classics at school. As a lieutenant he served in H.M.S. Barfleur under Sir Cloudesley Shovell, but had fortunately left his command by 1707 and so avoided probable death in the storm which drove four of the Admiral’s ships onto rocks in the Isles of Scilly and resulted in the loss of some 2000 souls, including the Admiral himself. As Vice admiral of the Blue in 1739 he led the capture of Porto Bello in the Caribbean, a town described at the time as “the only mart for all the wealth of Peru to come to Europe.” This made him a national hero

The Battle of Porto Bello

overnight. He was less fortunate in an attack afterwards on Cartagena (now in Colombia), another repository of Spanish gold which had provided rich spoils for Sir Francis Drake in an earlier age. Three other OWW, Captain Savage Mostyn (b. 1714) and Lieutenants Thomas Broderick (b. 1708) and Augustus Hervey (b. 1724) also took part. When Admiral of the White in 1745, he was struck off the flag list by George II for insubordination to the Admiralty, which meant the end of his career. Doubtless this had been a product of the ‘flamboyant style’ which contributed to the professional respect a series of crucial victories had gained for him.

A name as celebrated as Vernon’s is that of the Hon. Richard Howe (b. 1725) who, as a lieutenant, had served briefly in the former’s flagship. At the age of 22 he was appointed Flag Captain to Admiral Knowles. In 1755 his ship H.M.S. Dunkirk fired the first shots of the Seven Years’ War off the St Lawrence river. Two years later he took part in a failed attempt to destroy French ships in their home port of Rochefort, but in the process anchored 60 yards off a fort guarding the harbour and silenced all its guns in a matter of 35 minutes. Also a captain in this engagement was the Hon. John Byron (b. 1723), a schoolfellow of Howe’s. The battle of Quiberon Bay in 1759 involved yet another contemporary of his at the School, Captain the Hon. Augustus Keppel (b. 1725). He met Benjamin Franklin in 1774, but in the following year was unable to contact George Washington, with whom he had hoped to negotiate. He had been tasked with blockading the East Coast but, lacking ships and men of the quality required, could not prevent French support reaching the revolutionaries.

Like a number of other OW admirals, Howe combined a career as an MP with his naval commitments. He was prominent – and unpopular because of his insistence on reforms he considered desirable – in the House of Commons until ennobled by the King in 1782. On the same day he took H.M.S. Victory as escort to a large fleet of merchant ships carrying supplies for Gibraltar. Despite adverse weather conditions he avoided opposition and delivered them all safely. In 1788 he was granted an earldom. At the age of 68 in 1794 he was called upon once more to face the enemy. The result was a resounding victory over the French far out in the Atlantic, known thereafter from the date on which it fell as ‘The Glorious First of June’. However, it was thought by contemporaries in the Service that he should have made more of an effort to pursue enemy vessels that had been badly damaged. A summary of his 59-year service in the DNB reads: “His achievements were prodigious and must put him in the first rank of any of the naval commanders of any age”. Specifically, he presided over much modernisation – not least in simplifying the code of signals and encouraging development of the divisional system which survives to this day.

At Porto Bello in 1739 Lieutenant Thomas Broderick (b. 1708), serving ➽

under Vernon, led a landing party he sent to storm Castillo de Fierro. Such was his success that the Admiral then gave him his first command. As a Rear-admiral he was one of two OWW associated with Admiral Sir John Byng in 1757 when the latter decided to break off his assault on Minorca and return to Gibraltar. Subsequently he participated in the Admiral’s courtmartial. The following year he was Second-in-Command of the Mediterranean Fleet when his flagship H.M.S. Prince George caught fire off Ushant and, on being recovered from the sea after an hour’s swimming, he was found to be among the 250 saved from a crew of 800.

One of two OW admirals whose names reveal their kinship to major poets was John Byron (see above in the account of the Rochefort attack). As a teenager he was one of the few to survive when in 1740 his ship foundered off Chile, and “after undergoing the most dreadful hardships” he reached Valparaiso. In 1764 he was sent to survey the Pacific; but his heart was not in it so, preparing a negative report, he made his way home by the most direct route, and in doing this set a record for the circumnavigation! George, Lord Byron, was his grandson. The other was Edwin Tennyson d’Eyncourt (b. 1813), a cousin of Lord Tennyson, who became an admiral after serving in the Chinese War of 1841 and

John Byron

in the Baltic during the Crimean War.

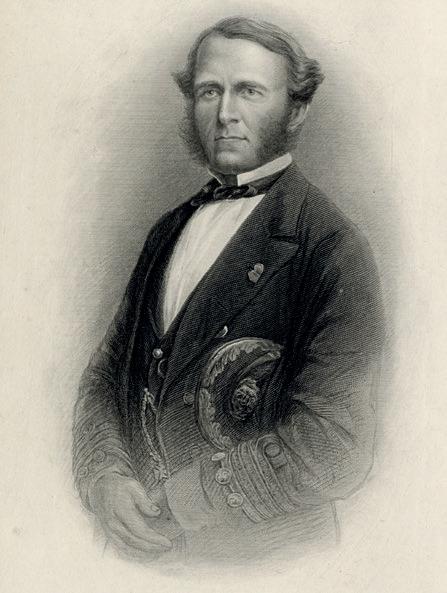

The Hon. Augustus Hervey (b. 1724), later Earl of Bristol, had a distinguished and apparently enjoyable career. As a lieutenant stranded in Lisbon while his ship underwent a refit there in 1740 he was made welcome by the ladies of that city, and is recorded as later conducting amorous affairs in several Italian ports. Another side of his character was seen at Livorno in 1748 when a merchantman loaded with explosives caught fire. No other vessel dared approach it, but he towed it out to sea where it exploded, singeing his coat but causing no other damage to his ship. The next year he (perhaps not unexpectedly) parted from his wife. In 1756 he joined Byng’s fleet investing Minorca and advised him against his fatal decision to withdraw to Gibraltar. He subsequently wrote a strong defence of Byng. From 1758 he combined successful actions against the French with sitting as MP for the ‘family seat’ of Bury St Edmunds. As a Lord Commissioner of Admiralty from 1771 he contributed to significant reforms of the Navy’s administration.

Captain Sir Charles Cotton Bart. (b. 1753) served under Howe on the Glorious First of June in 1794 and with Captain the Hon. Henry Curzon (b. 1765) the next year under Admiral William Cornwallis in an encounter with the French off Brittany which became celebrated as ‘Cornwallis’s

Augustus Hervey

Retreat’ – not to be confused with the humiliating surrender of Yorktown 11 years earlier by his elder brother, General Charles Cornwallis. Here the Admiral, in command of a few warships escorting a convoy of unarmed vessels, pursued by a larger and faster French fleet, hove to and faced the enemy after ordering the convoy to disperse. The British held out until the French turned away, suspecting the approach of (non-existent) reinforcements for their enemy. With the entire fleet safely home there was national rejoicing, while Cornwallis received many honours.

When and how did any of our admirals cross paths with Nelson? William Hotham the younger (b. 1772) served as a volunteer under Nelson at the Siege of Bastia, Corsica, in 1794. The next year his uncle, Vice-admiral William Hotham (b. 1736), took a fleet out of Livorno against the French, and fought an action in which victory was convincingly attributed to Captain Nelson of H.M.S. Agamemnon, who made no secret of his displeasure that he had not been allowed to finish off vessels which he believed could easily have been overtaken and despatched. As captain of H.M.S. Lively the Hon. George Stewart (1768) took part in the Battle of Copenhagen in 1801. At Trafalgar the only OW aboard H.M.S. Victory was Midshipman the Hon. Ralph Nevill (b. 1786). Captain Eliab

James Goodenough

Harvey (b.1755) followed the flagship in command of H.M.S. Temeraire. Although not a participant in the battle, Commander Peter Parker (b. 1785), in command of the sloop H.M.S. Weazel at the age of 20, was in a squadron watching Cadiz, and saw the Franco-Spanish fleet emerging at 6am on 20th October, signalling this to the main fleet. His vigilance was rewarded after the battle by Collingwood who then promoted him to captain. In a ‘postscript’ action on 22nd October, Captain the Hon Henry Hotham (b. 1777) commanded one of a fleet stationed in the Bay of Biscay which met and captured a French squadron fleeing Trafalgar. In 1815 Hotham, again off the French coast but now Rearadmiral leading the blockade, forced Napoleon to cancel a plan to flee to the USA after his defeat at Waterloo.

James Goodenough (b. 1830) was involved as a lieutenant in escorting convoys of French troops and Russian prisoners of war in the Baltic during the Crimean War. From there he went to serve in campaigns around China, where his detachment armed with field pieces assisted in the capture of Canton. The year after his promotion to captain in 1862, he was sent by the Admiralty to the USA with instructions to make a report on the ships, guns and personnel of the Union Navy. Not least because Britain was known to favour the Confederate cause, it is surprising that his enquiries were not only tolerated but accorded the active cooperation of every specialist officer he approached at all the principal naval bases except Charleston, where perhaps the proximity of the enemy made for extra caution. Available for study at the National Archives in Kew are the report itself in a decaying hard-back account book and a series of letters he sent to Their Lordships as he moved from one centre to another, all written in a clear script and, where the guns and engines are concerned, described at a level of technical detail that would not be expected of most seaman officers. The authorities supplied Goodenough with engineers’ drawings to accompany his text. Each topic covered incorporates tables of precise figures all the way down, for instance, to the number of officers in

every rank. There followed appointments to various European countries as naval attaché and then in 1873 as commodore in charge of the Australia station. This included supervision of British interests in Pacific islands regarded as protectorates, one group of which, the Santa Cruz archipelago, he was visiting in 1875 when he was struck by a native spear and developed tetanus, from which he died. His son, Admiral Sir William Goodenough, commanded the 2nd light cruiser squadron at the Battle of Jutland with some distinction.

Mention should be made of an OW sailor John Hallett (b.1769) who, as a midshipman in 1789, was one of 17 crew set adrift in the Pacific with their captain, Lieutenant William Bligh from H.M.S. Bounty in the mutiny that became a legend. After nearly seven weeks they reached Timor. Both he and Bligh were court-martialled but acquitted, and Hallett was even promoted to Lieutenant. Sadly, however, that was the end of his career as he died four years later of the effects of his ordeal.

Although far from comprehensive, this account of Westminster’s association with the Royal Navy should give some idea as to how varied were the experiences offered – chiefly by hostilities between the colonial powers of Europe in the 18th century – to any young man with a taste for military service at sea. Not least of the opportunities was for success in battle to be rewarded with large sums of prize money. Admiral Legge’s career at the end of the Stuart period was soon followed by the Navy’s adoption of a more formal structure. With the coming of the steam engine, iron plates of armour, and advanced weaponry in the 19th century, the conduct of sea warfare underwent dramatic change up to World War I, when Captain (later Admiral) Phillimore shared in Britain’s first successful action against Germany at the Falkland Islands in 1914. OWW have occupied senior posts in the Royal Navy less frequently over the succeeding century, but their stories too should be worth telling in time to come. ■