5 minute read

The Neville Walton Travel Award

Jamie Voros (MM, 2010-12)

Location: Kathmandu, Nepal

Advertisement

epal is a beautifully remote country, many thousands of metres above sea level. My ears did not pop as the plane came into land on one of the world’s shortest commercial runways in Kathmandu. At 14,000 feet up we were almost landing in the clouds. The mountainous beauty promised by the view from the plane was striking, particularly given that just one year before my visit, Nepal had been rocked by a series of devastating earthquakes. Many families were displaced initially, and one year on many still did not have access to proper shelter. I jumped to the conclusion that so many people were experiencing serious problems with housing this far on because shelter design appropriate for the climate and lack of materials must have been major hurdles.

Nepal’s lack of housing in the wake of its earthquakes sounded solvable through intelligent design and engineering. These ideas gave rise to the topic of my bachelor’s thesis: a transitional shelter for Nepalese earthquake victims. Transitional shelters are a form of rapidly buildable housing that displaced people can live in until they are able to find permanent housing. Typically, a transitional shelter is designed specifically for a certain disaster or population. After nine months of design iterations, running simulations and reaching out to anyone familiar with Nepalese culture I produced my own transitional shelter design. ➽

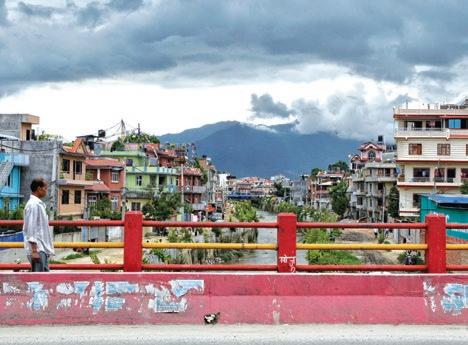

Upon arriving in Kathmandu, I was greeted with a cityscape completely different from what the media had promised me. I was taken aback by how quickly the condensed, dusty city melted away into rural greenery. Even the constant swerving and sharp breaking amidst a cacophony of blaring horns and flashing headlights was not enough to keep me from noticing that most of the buildings hardly looked hit by an earthquake. Among the mass of buildings, wires and uneven winding roads, few buildings were still sporting visible damage, they were like gap tooth holes on the block. I later learned that the people who got hit hardest by the earthquakes and were still feeling the brunt of their effect were those living in rural areas surrounding Kathmandu. While there were buildings in the middle of Kathmandu affected by the earthquake, the easy access to labour and materials made them a lot easier to repair, rebuild or at least cordon off the damaged parts. The hotel I was staying at had closed a large portion of its rooms due to earthquake damage, but

had done an excellent job of fixing up the outside and keeping unaffected rooms open.

In preparation for the trip, I had reached out to the ends of my network to get in touch with the Nepal Red Cross and Open Learning Exchange (OLE). The OLE is an initiative started in 2007 to provide better education to school age children across all of Nepal through integration of technology and technology infrastructure.

I met with Mukesh Singh of the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC). He explained the full repercussions of the earthquake aftermath, far beyond the lack of housing, going from the initial lack of food to loss of schooling in rural areas. The main complication and what seemed like the major hurdle to the Red Cross’ efforts was something that I had not recognised at all. Despite being a third world country, the amount of red tape imposed by the system (such as where governmental funding was allowed to go and clearing customs) held back efforts. Initially, when the

Nepal Red Cross organised food to be flown in and transported, the inefficiencies in clearing customs caused the majority of it to go bad at the airport. He talked about problems with donations: a significant amount of food that was sent over contained beef and Nepal is a largely Hindu country.

Beyond learning of new problems I was also able to verify concerns I had addressed but not fully resolved during my thesis, mainly that without good communication with the people you hope to provide housing to it becomes very difficult to provide it effectively. A classic example is where housing is built and left unused because it does not cater to the communities and culture in rural areas. I learned that often Nepalese people would rather stay on their own land with their families than move to an emergency housing facility.

I had the opportunity to meet with Rabi Karmacharya of the OLE who very kindly discussed social repercussions of Nepal experiencing an earthquake in terms of loss of schools and access to education. During the time I was in Nepal, the OLE was experiencing difficulty finding labor to re-construct schools in rural villages, despite offering at or above market rate wages. The OLE even offered to pay parents and people already in the villages, but too many of them chose not to accept a temporary paid position to reconstruct schools for their children.

Being able to see the state of Kathmandu and the surrounding area, coupled with the interviews I conducted at the Nepal Red Cross and OLE, opened my eyes to the problem as a whole. The kind of damage suffered is different to that which the media portrays; not only are there many houses which are completely destroyed, but there are also many only partially standing in unsafe conditions. House design is completely necessary to restore conditions in the aftermath of an earthquake, but it is only one small part of the solution to a much greater, systematic and physical problem.

Most importantly, the physical problems that arose from Nepal

experiencing such a huge natural disaster are just the tip of the iceberg. It is not just an issue of rehoming people; it is an issue of repairing the physical ties within the community. That is reconstructing social connections as well as clearing road blocks and rebuilding homes in a way that the people will actually appreciate and use.

I am immensely grateful to the Neville Walton Travel Award and Westminster School for allowing me to put the last piece of my thesis in place: actually visiting Kathmandu. I am very lucky to have developed a cultural understanding of the problem and was able to explore why design is only part of the solution when it comes to rehoming displaced people. My travel to Nepal has equipped me with incredibly valuable knowledge to continue down this path and work out the next steps. ■