11 minute read

Feature: Spotlight on Thomas Burke

Spotlight on...

We have many interesting and inspiring characters amongst our alumni, going back over 200 years. In this regular feature, OR Andy Wotton (Mullens 1975), points the spotlight on one of those characters… Thomas Burke. It is a fascinating read!

Advertisement

The Burke Society

In 1958 the School’s Headmaster, Robert Drayson, announced the creation of the Burke Society, ‘to encourage debating, literary activity and the art of discussion’. Its membership was drawn from the Sixth Form initially but it was seen, by some, as elitist and slightly mysterious. Whether these views were fair or not, the perception continued, on and off, for the duration of its existence. The last mention of the Society was made in the Reedonian magazine in 1997. Throughout its life, however, the Burke Society had many outings, debates and discussions and, occasionally, attracted a distinguished guest, arguably the most prominent among them being Sir Barnes Wallace, the inventor of the ‘Bouncing Bomb’.

The Society was named after Old Reedonian, Sydney Thomas Burke (to use his full name), a very prominent author of his time, but whose personal story was never known or told. Indeed, when he died in 1945, the Times obituary used material taken from one of his books (The Wind and the Rain) which was believed to be (but was not) autobiographical… now is our chance to shine the spotlight on the life of this fascinating individual.

The boyhood of Thomas Burke

Thomas Burke (he dropped the name Sydney) was born at 9.15pm on Thursday 29th November 1886, and how do we know this? James, his father, wrote the details down in the family bible. James was married to Emma Williams, his second

wife, 24 years his junior. Their first child, Annie Louisa, was born in 1884 in Lambeth and Thomas followed two and a half years later.

Sadly, James Burke died four months after his son’s birth. He had been the Manager of the Army Clothing Depot in Pimlico (now the site of Dolphin Square) but did not earn a large wage and, thus, had little savings put aside. Although Emma had affluent relatives (her cousin was Sidney Arthur Alexander, Canon of St Paul’s Cathedral), she remained proud and independent of any potential help they may have offered to bring up her two children.

Instead, when Thomas was six months old, Emma secured the position of Housekeeper to a wealthy titled family who owned property in Portland Place in London and Ware Park House, a county mansion in Hertfordshire. During this time, Emma taught her children, but by the time Louisa (as she was then called) was nine and Thomas was seven, Emma decided her children needed formal education and so they went to All-Souls Church near Portland Place. Thomas was bright and a quick learner but his general health was not particularly robust, being very slight and only five feet three inches in adulthood. The next move would have been to an inevitable job in a factory, which Emma knew would not best suit her son. So, at the beginning of 1897, she decided to apply for a place at the London Orphan Asylum in Watford, which was only 25 miles from Ware Park House. Her application was successful and, in June 1897, Thomas was admitted along with 33 other boys.

An inquisitive soul

It is clear from some of Burke’s early writing that he resented going to the School, but that resentment was more aimed at his mother for sending him there rather than a reflection on the School itself. Whilst it wasn’t all plain sailing, he was a model student and a bright one and, in later life, he wrote warmly about his five years at Watford. His main frustrations seem to have been around being constrained by the rules and not being able to apply his initiative.

Thomas left the School in October 1901 and, aged 14, was placed as a clerk in a bank in London called Stilwell & Sons; his sister was a cashier in the City and the family were living in Clapham. However, Thomas hated the tedium at the bank so, after a year, left and found another office clerical job, which wasn’t much better. Once he had mastered the routines, which didn’t take long, boredom set in once more.

Travelling by tram and bus to and from work, Thomas used to let his mind wander as he looked down the side streets and alleyways, later actually taking to walking down them. This was a fertile breeding ground for his imagination and he never looked back. In Son of London, a book published posthumously in 1946, he wrote, ‘only genuine life is in the imagination which is the food of the spirit, and which no material circumstance or outer turmoil can ever trespass upon or soil.’

It was around this time, in 1903, that Burke began to write properly, having given up his boring office position and securing a job in a second-hand bookshop. The owner wanted someone to mind the shop during daylight hours, when it was relatively quiet, an arrangement that suited Thomas very well, because not only could he expand his reading, but he could also do some writing. By the time he left the bookshop in 1905, at the age of 19, he was a very well read young man.

Cazenove and Perris

The year 1905 was to be a very significant one for Thomas, although initially it did not start well. Thomas made an appointment to meet Mr Charles Cazenove of the literary agents, Cazenove and Perris, to seek support for the publication of some short essays. Although he was 19, Burke looked more like a 13-year-old, especially wearing his old school cap for the meeting! As such, Mr Cazenove breezed past him as he sat waiting. It was only when Burke was later announced, did Mr Cazenove exclaim, ‘Good God, I wasn’t expecting the author of those sketches to be a schoolboy!’.

It appears that nothing tangible became of the sketches, but Thomas Burke emerged from Charles Cazenove’s office with a job at the literacy agency, where he remained for the next seven years. Burke and Cazenove had a great mutual respect and the younger man saw his elder as the kind of father figure he had never known.

Spotlight on...

As time went by, Thomas was given greater responsibilities within the firm, something he much appreciated.

Unlike many of his School’s former pupils, Thomas did not fight in World War One. He was too small and too weak physically to pass the medical, but he did work for the Ministry of Information towards the end of that conflict.

Sadly, the literary agency closed in 1914, because Cazenove was ill and business had declined, meaning that Thomas was out of work. All was not gloom and doom, however, because in 1915 the publishers, Allen & Unwin, published Burke’s first book, Nights in Town: A London Autobiography. Thomas was now 28 and, later that year, went to work at Fleetway House in Farringdon Street at the offices of the journalistic mogul, Lord Northcliffe. It was there he met Winifred Welles, who, three years later, he would marry.

No such thing as bad publicity!

Whilst Nights in London had modest success, his next book, Limehouse Nights published in 1916, burst on the scene and placed Thomas Burke amongst the most

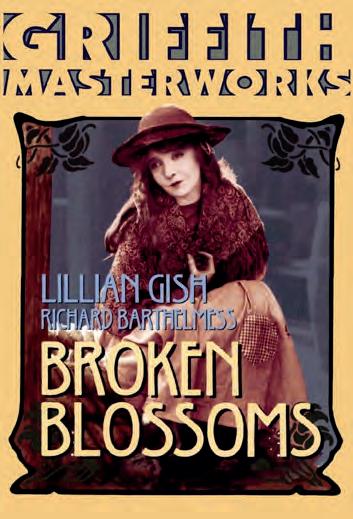

Founders of United Artists (from left to right): Douglas Fairbanks, Mary Pickford, Charlie Chaplin, and film director Derek Griffith

talked about authors of his time. The book was really a collection of short stories which focused on the growing tensions around the Limehouse Chinese community who were associated with vice, drugs and gambling. Burke’s book tapped into these feelings and conjured up the remote and dark alleyways of the old London docklands. For some circulating libraries, it was too intense and the book was banned from their shelves, the result of which was to boost its sales!

In whatever way the book is viewed today, and almost certainly there will be some who would be disparaging about it, Limehouse Nights put Thomas Burke on the literary map. So much so that one of his short stories in Limehouse Nights inspired the first film produced by United Artists.

On 5th February 1919 celebrated actors Mary Pickford, Douglas Fairbanks and Charlie Chaplin, together with film director Derek Griffith, formed United Artists to allow film artists greater say and control over their work. It was Mary Pickford who brought Limehouse Nights to the attention of her fellow actors; on 13th May, the film, Broken Blossoms, was premiered in New York and was a big box office success. Before the film release, the book had been printed eight times; afterwards, a further seven editions followed.

By the early 1920s, Burke had seven of his books in print in England and the US; his finances were sufficiently sound for him to purchase a villa in Folkestone for his mother and sister and a flat in Highgate for him and Winifred, who was also a writer.

Confidante of Charlie Chaplin

In 1922 Charlie Chaplin, by now a film super star and known the world-over, decided to make a trip to London. He was keen to visit some of his childhood haunts, but most particularly he wanted to meet Thomas Burke. Chaplin never revealed the exact location or date of his birth, but it was widely believed to have been very close to where Burke was born in Lambeth. Chaplin, who disliked crowds, was not happy with the original idea of Burke conducting a group tour so arrangements were made for the

gentlemen to meet at 10pm at Burke’s home.

Chaplin was fascinated and yet slightly puzzled initially by his host. He wrote, ‘He is very curious. Doesn’t seem to be noticing anything that goes on about him…I am warming to him considerably… Is his reticence real, or is this some wonderful trick of his, this making his guest feel superior?’.

After conversing for a while, the two men set off on their stroll together towards no place in particular. They chatted about Limehouse Nights, but Burke was silent for long periods. Chaplin said, ‘And then I awaken, I see his purpose. I can do my own story – he is merely lending me the tools…’ Chaplin understood that Thomas had already shared the stories in words and now was telling them visually. He wrote, ‘Every once in a while, Burke lifts his stick and points. His gestures need no comment. He is most unusual. What a guide he is… I feel that he has gauged me quickly, that he knows I love feelings rather than details.’ The pair walked until 3am before returning to Highgate, clearly enjoying each other’s company. Chaplin concluded, ‘He would sit there immobile, yet he drew me out. I felt I wanted to unburden my soul to him, and I did. I was at my best with Burke.’

It was ten years before the two men met again, but the friendship forged that night in Highgate and Limehouse never ceased and remained strong until Thomas Burke’s untimely death.

Endorsement by Alfred Hitchcock

In recognising his success, in the same year that Burke met Chaplin, Thomas’s photograph appeared in a book of portraits by Alvin Langdon Coburn. The book was called More Men of Mark and included literary giants such as Thomas Hardy, Ezra Pound and Joseph Conrad. Thomas was in exalted company. In late 1924, Thomas and Winifred moved to a flat at 33 Tavistock Square in fashionable Bloomsbury, the literary centre of London. However, Thomas was not part of it, being unbothered by such literary gatherings. Burke wrote over forty books and short stories, as well as poetry, covering both fiction and non-fiction topics, but in 1931 he published a crime thriller The Hands of Mr Ottermole which became a best seller. In fact, some described it as the best crime story of the 1930s and in 1949, four years after Burke’s death, a panel of critics voted it the best mystery of all time.

In 1957, Alfred Hitchcock - that doyen of the murder mystery and suspense – presented the story on television in his series Alfred Hitchcock Presents.

The End

On 3rd May 1932 Thomas’s mother, Emma, died at her villa in Folkestone, aged 85. Tragically, Thomas’s own life came to an end at the Homeopathic Hospital in Great Ormond Street on 22nd September 1945. The cause of death was peritonitis following a perforated gastric ulcer; he was just 58.

The Post-script

For several years during the 1960s, an American writer from Philadelphia, Josephine Shotwell, had been in correspondence with Louisa Burke and others about Thomas with the intention of writing his biography. Sadly, this never came about because Josephine died in January 1968. She did, however, type up where she had reached in the story of Thomas Burke, the year 1929 and, through good fortune, her manuscript and some of her working papers were given to the School in the mid-1980s. They have lain, undisturbed, until now.

Maybe one day, the full story of Thomas Burke will be revealed, for he was undoubtedly a scholastic and enigmatic man… perhaps these are the traits Mr Drayson was looking for when founding the Reed’s Burke Society and why it was perceived in such a similar way!

The full version of this article, written by Andy Wotton, can be found on the Reed’s Heritage website: reedsschoolheritage.co.uk

A rare photo of Charlie Chaplin and Thomas Burke 1922

(copyright Roy Export Company Establishment, scan courtesy of Cineteca di Bologna)

If you’d like to learn more about the School’s history register on the Reed’s Heritage website and explore...

If you would like to contribute an article or a memoir or an artefact, please contact heritage@reeds. surrey.sch.uk for more details. We’d love to hear from you.