7 minute read

To The End

Anna Lipari

I found the end of the world underneath the cell-phone tower at the top of the hill. The tall orangewhite spire, crowned with a single blinking red beacon, floated like a neon buoy over the fog-washed evergreens; it was October, early evening, and the lights of the neighbor’s houses were already on, their faint yellow glow leaking out of the windows and spilling across dark sidewalk-puddles like an oil slick. I could have sworn I moved away from there years ago, that I left behind the house I grew up in with its long dim hallways and the greying roses on the kitchen wallpaper and the dark, serrated silhouette of the pinecrested hill looming over the backyard. There had been a time when I packed up suitcases and took myself to a college dorm, and then later to a little white-walled blank-slate apartment in the middle of a city. But no matter how many times I left I always seemed to end up back there, walking in those grey streets, always in the direction of that tower. I think there used to be a barbed wire fence around its base, but at that point it was long gone. The end of the world was resting at the foot of the tower in a nest of steel cables, seeping soft static into the stagnant air.

Advertisement

“Well,” it said.

In the evenings, it got into the habit of sitting in the corner of the living room, tucked between my great-uncle’s frayed red wingback armchair and the crystal lamp with the burned-out bulb. “It’s almost time,” it told me one night, after we’d been living in that empty house together for long enough that I was used to seeing it there, casting backwards shadows and humming softly to itself. A year, maybe, or a week. I was kneeling in front of the fireplace, burning it a sacrifice. The fireplace was where my grandmother used to light juniper branches every December. We’d bring them back from the desert for her each Thanksgiving, wrapped in grocery bags and tied with twine; the brown paper would catch flame and peel away, and the skeleton of the branch inside would glow vermillion, and the whole room would smell like open sky. I was trying to strike a match, but I’d never been all that good at it, and I kept getting nothing but little curls of smoke. “We haven’t got long,” it said.

“I know,” I said. “I’ve known for a long time now. I think it has something to do with that tower.”

“I’m thinking next Thursday,” it said. “For the world to end, I mean.”

“Oh, sorry,” I said, “I think I have a meeting on Thursday.” I tried to strike the match again. My hands shook too much, though, and the spark fizzled out before it had even started.

“Friday, then,” it said. It always did care about me like that.

I said that Friday was fine. When the match finally struck, I was surprised by how high the yellow flame flared, how it licked at my fingertips and dripped down across the hearth. The offering-‒a scrap of melody from a commercial I saw when I was a kid, I think, or else it was a button I lost in the gap between the basement stairs, or one of my baby teeth, or my first kiss-‒caught fast and burned away.

mornings, I fed it orange peels and bits of poetry and told it all my best-kept secrets. “Who are you?” it asked me, once. This was right after I first carried it home with me from the cell-phone tower, when it was perched on the green-speckled laminate kitchen counter and I was staring sideways at it as I poured myself a bowl of cereal, when we were still getting to know each other. “I’m sure you already know my name,” I said, “You must have learned it all those “At night, the end years ago, when I was a lonely highof the world slept school kid. I would always go for walks up on the hill, remember? When curled up at the foot I needed to get out of the house. I kept circling the tower like I already knew of my bed.” you were there.” “You could pick a new name,” the end of the world said, “if you wanted

At night, the end of the world slept curled up at the foot of my bed. I could feel it through the comforter, hot and heavy like one of those black-hole diagrams in a high-school physics classroom, buzzing quietly like a broken radiator. Sometimes it picked up radio signals, spat out grey static and fragments of sugary pop hits, distorted and warped so that the soundwaves buzzed back and forth inside my ribcage and resonated in the hollow behind my sternum. In the to.”

I frowned and looked down into my cereal bowl.

There wasn’t much in there-‒I was on my last carton of milk, and the cashier at the grocery store had said there wouldn’t be any more this season. Beautiful farm country down there. I wish I’d been able to visit before the fires got so bad. Well, maybe next year, eh?

“Who are you?” I asked the end of the world.

“I’m the end of the world,” it said, and I couldn’t argue with that.

The living room, again. Wednesday evening. The sky was dark with smoke, the air blinking red; the whole universe ached in time to the pulse of the beacon on the hill. The end of the world was kneeling over my shoulder, in front of the fireplace. I could feel the gentle warmth of it like gamma radiation on my skin, could taste the dust and cobweb of it coating the inside my lungs. “Does the world really have to end?” I asked. “You don’t think there’s anything we could do, any way to stop it? I mean, there are a lot of people out there who would want to help do something, if they just got the opportunity, you know?”

The end of the world smiled, a warm, sad sort of smile. One with teeth. “Don’t cry,” it said, but I hadn’t even realized I was crying until then. The end of the world curled itself around my shoulders, soft as rotten velvet. It leaned down. It kissed the back of my hand.

When I lived in the apartment there was a city bus that stopped under the window of my bedroom every half hour, all night long. We kept the curtains down, but washed-out neon light would still slip in through the gaps between the blinds and slide across the ceiling of the room, and I could hear the heavy pneumatic sigh of the bus kneeling at the curb, the smooth robotic voice offering a garbled welcome. “Number forty-four to Council Square,” it would usually say. “The doors are closing.” Except some nights, when I’d been awake for hours already, when the bus had come and gone three or four or a hundred times, it would mutate into something different. “To the end,” it would sing, “to the end, to the end. Come home.”

The girl who slept next to me never woke up when the bus came. I would reach out and find her hand in the darkness. I would hold tight and keep my eyes closed until the blinking red light had faded from the white walls of the room and the lumbering mechanical thing outside our window had passed us by. Until the inevitable had been delayed, at least by another half-hour.

What I mean to say is, I was in sixth-grade science class when I first learned that we were all living in borrowed times. What I mean to say is you’ve always been with me, wrapped around the back of

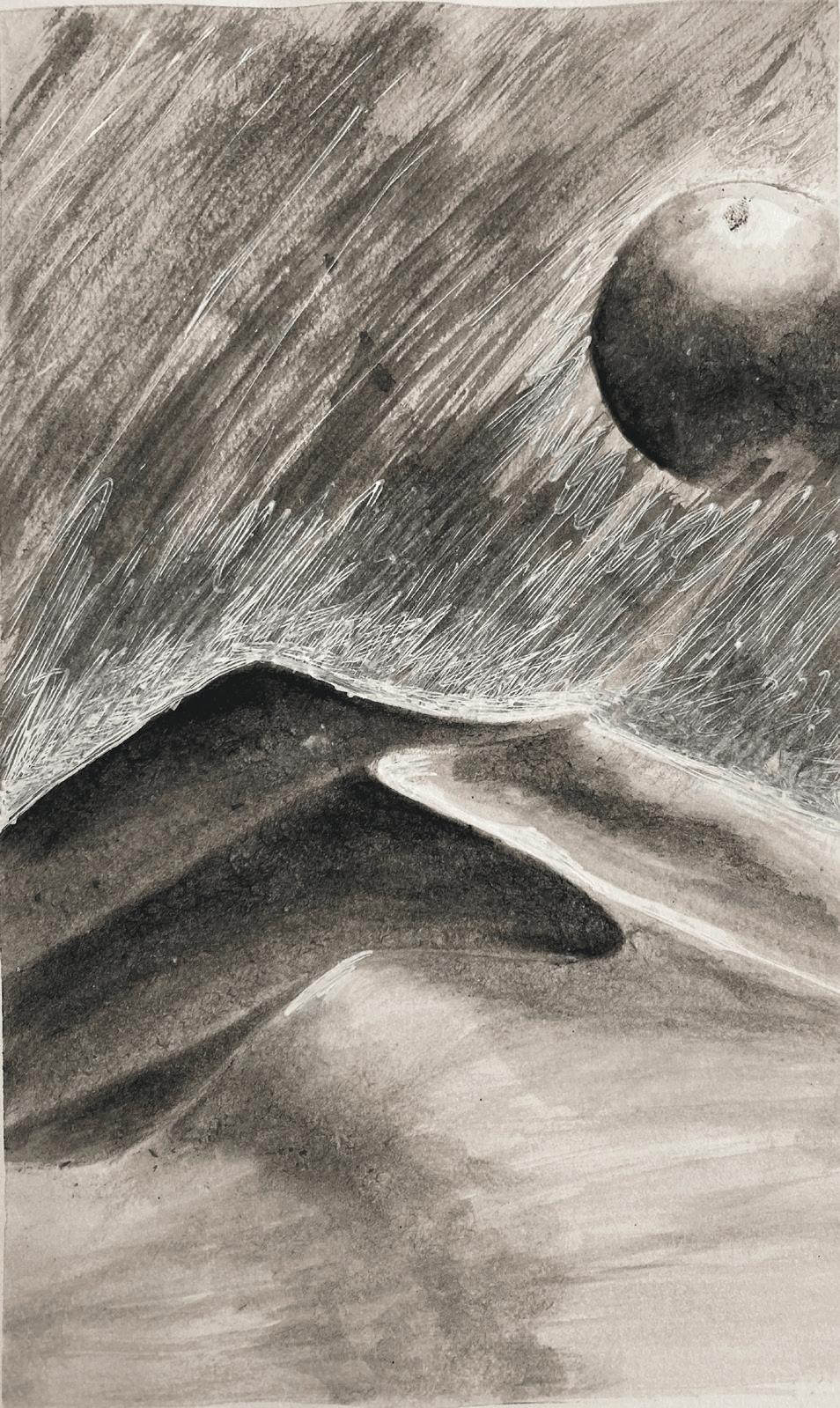

Longing | Ivan Kwei | ink on paper my brain stem. I wasn’t surprised to meet you there, waiting for me at the top of the hill. I wasn’t surprised to end up back in that old house under the darkening, smoke-smothered sky, to smell that last enduring hint of juniper, as if I had only ever stepped out for a few moments. I don’t know where the grandmothers and great-uncles who used to sit around the fireplace and drink champagne every New Year’s Eve went; I don’t know where the girl from the city is now. I hope she didn’t miss me too much. But I am glad to have had you there with me, in the end.

I don’t remember what the meeting on Thursday was about. It ran late, and when I got home I fell into bed, and I was thinking about the dishes in the sink and the phone calls I still needed to make, and I forgot all about the world ending until I woke up the next morning, and by then it was all over.

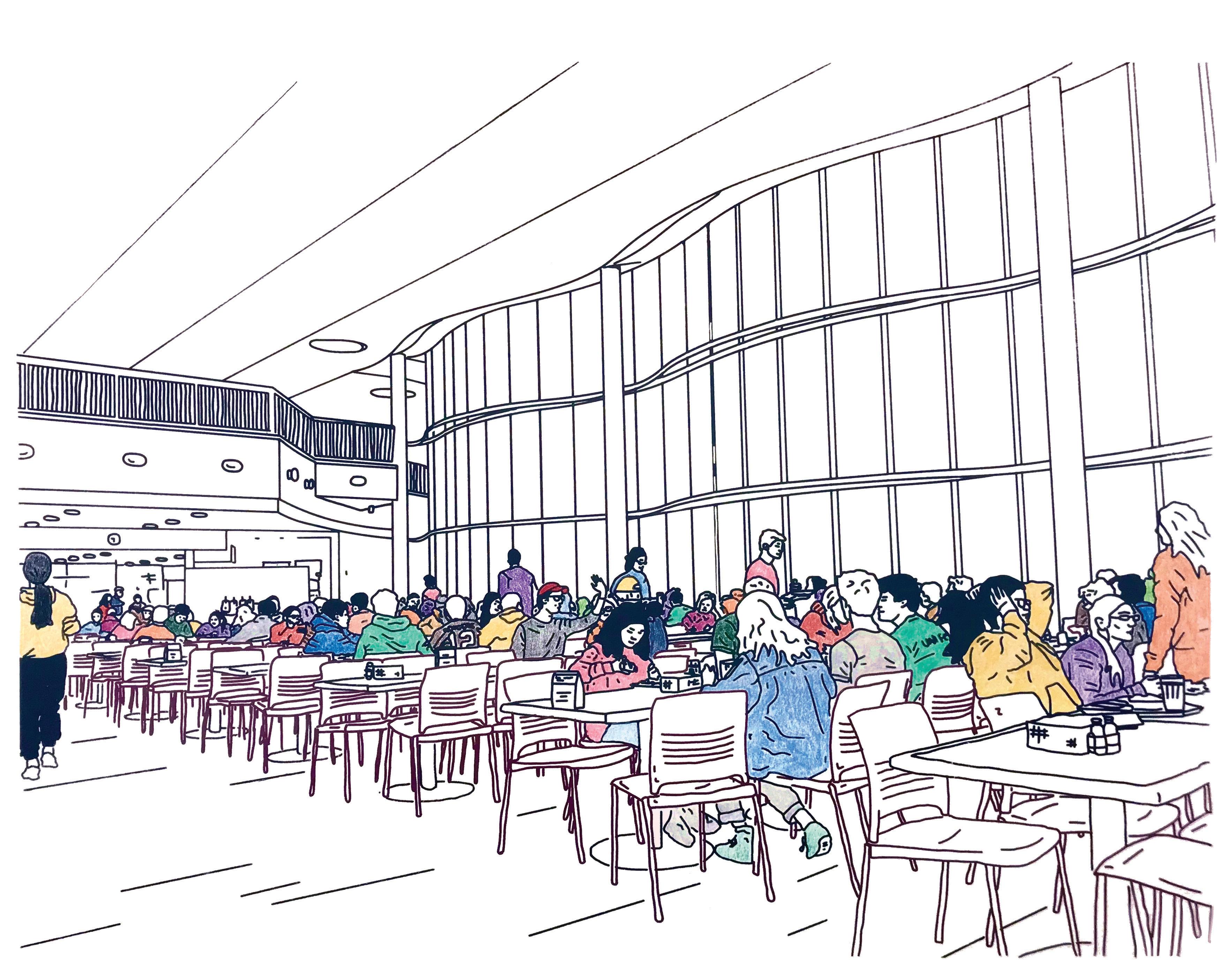

Dhall 2019 | McKenna Doherty | multi-colored screenprint with illustration