Welcome to the final edition of Nursing in General Practice for 2022. Once again, this month’s edition reflects the diverse nature of the general practice nurse’s (GPN) role. Whether you are new to general practice nursing or an experienced GPN, the articles featured in this issue provide both new knowledge and an opportunity to update.

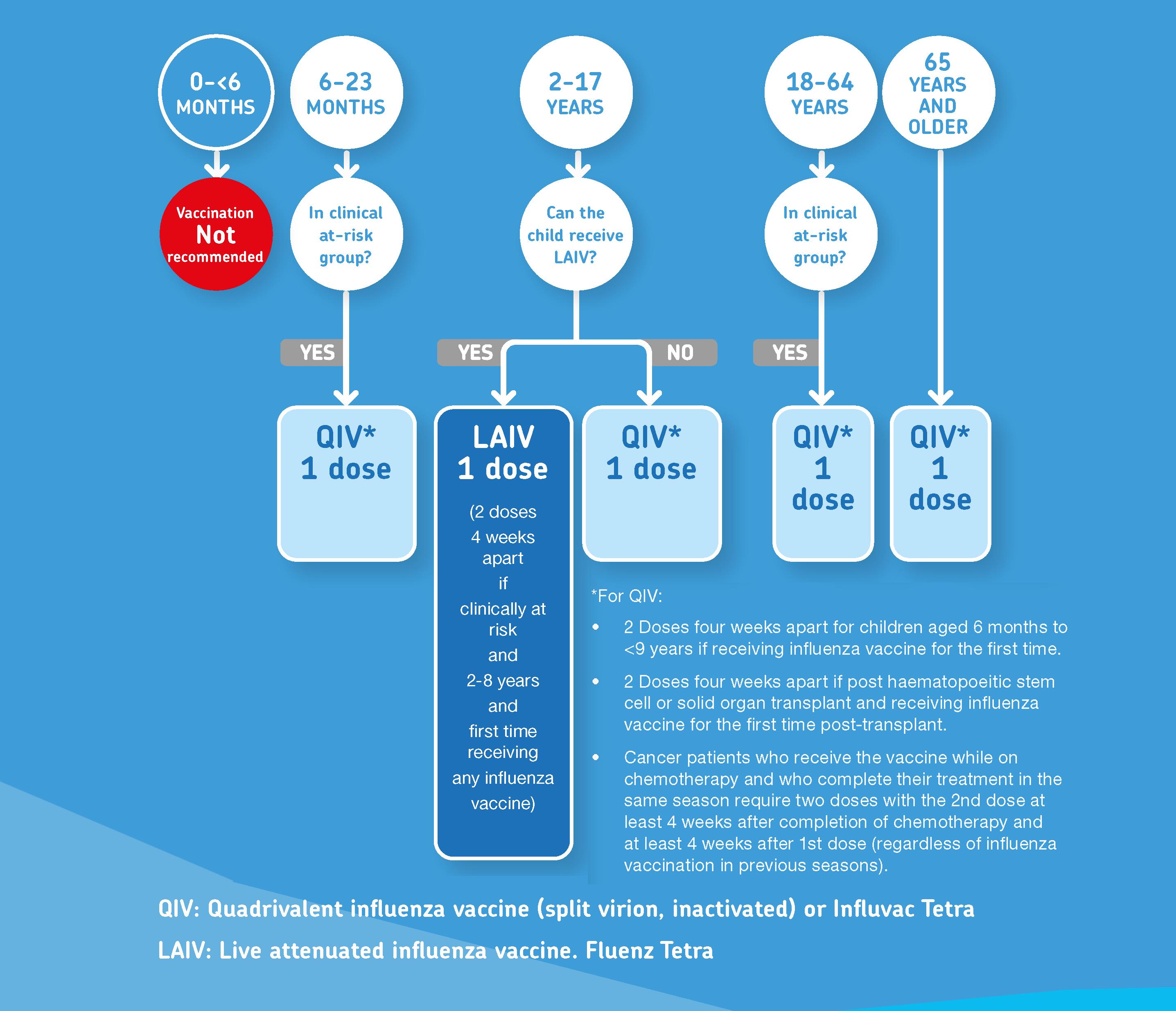

Firstly, there is a double feature on immunisation, with one article focusing on influenza and Covid-19 vaccines and a second article on monkeypox vaccine by Dr Tom Barrett from the National Immunisation Office, who is well known to GPNs for his frequent support. Immunisation is such a rapidly changing area and accounts for a large volume of the GPN’s workload. We welcome Dr Barrett’s contribution to this edition.

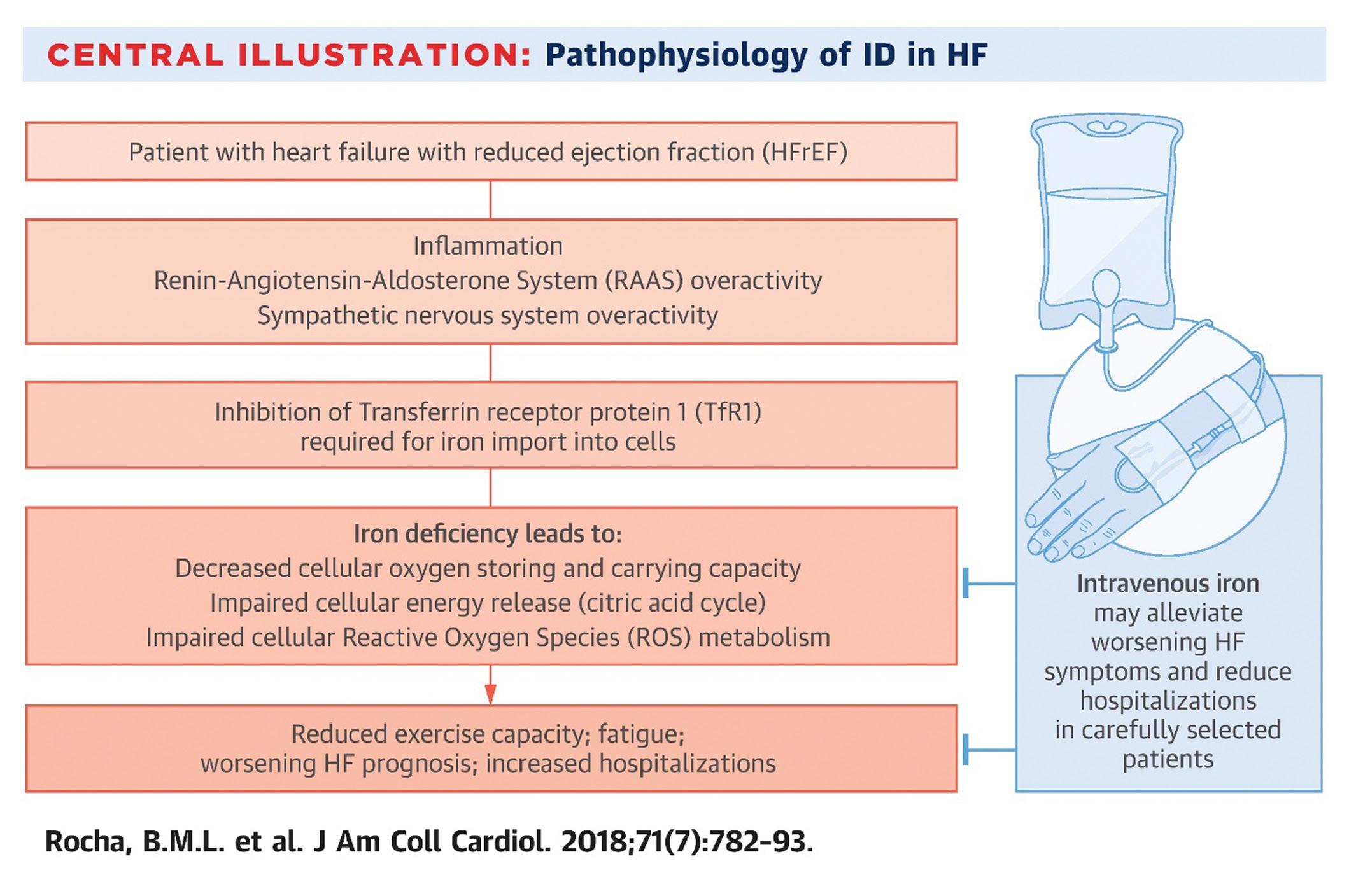

Iron deficiency in cardiology is the focus of a new NurseCPD module. Dr Patrick O’Callaghan, Consultant Cardiologist, and Dr Robert Evans, SpR in Cardiology, are the authors of this module. The module provides an overview of the latest approaches and evidence in treating iron deficiency in patients with cardiovascular issues. This module is available on NurseCPD at: www.medilearning.ie/nursecpd/iron-deficiency-in-cardiology-_-2022.

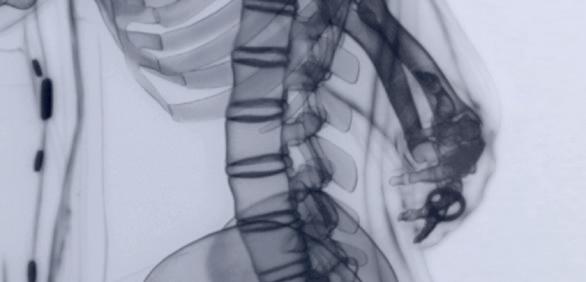

Priscilla Lynch outlines the major highlights from the Irish Osteoporosis Society's Annual Medical Conference in October. She discusses the impact, prevention, and management of bone

disease, 'health passports' for children, the importance of pelvic floor training, and other issues of focus from the event.

November is a busy month for health awareness days, with two of the chronic disease management conditions being featured – diabetes and COPD. This year sees World Diabetes Day being held on 14 November. Every year, the World Diabetes Day campaign focuses on a dedicated theme that runs for one or more years. The theme for World Diabetes Day 2021-23 is ‘Access to diabetes care.’ Access to diabetes care in Ireland has improved dramatically over the past 20 years. As hospital diabetes teams are slowly being integrated into primary care, this will make diabetes care even more accessible for patients, as care will be delivered locally. Priscilla Lynch

provides a comprehensive overview of the new NICE Guidelines for type 1 diabetes management.

Also taking place, is World COPD Day. The 2022 theme for World COPD Day is ‘Your lungs for life’ and it takes place on 16 November. This year's theme aims to highlight the importance of lifelong lung health. From development to adulthood, keeping lungs healthy is an integral part of future health and wellbeing. This campaign focuses on the contributing factors to COPD from birth to adulthood and what we can do to promote lifelong lung health, as well as protect vulnerable populations. The article in this issue provides an overview on diagnosis and management of stable COPD.

We would like to thank all the contributors to Nursing in General Practice during 2022 for their expertise in producing relevant, up-to-date, evidence-based articles, and we look forward to working with you again in 2023, while welcoming new contributors.

Wishing all our readers a peaceful Christmas and a happy, healthy, and prosperous New Year. l

NiGP is now a fully independent publication and is no longer the official journal of the IGPNEA. If you are interested in writing an article for NiGP, please email denise@greenx.ie.

The latest Irish healthcare news

INTERVIEW

Oncology Nurse Specialist, Geraldine Mullan, talks to NiGP after winning ‘Local Hero’ award 14

CPD: IRON DEFICIENCY IN CARDIOLOGY

Cardiology experts, Dr Robert M Evans and Dr Patrick O’Callaghan from University Hospital Waterford provide an evidencedbased update on iron deficiency in cardiology patients

Ruth Morrow delivers an extensive overview of the diagnosis and management of stable COPD

Highlights from the

EDITOR

Denise Doherty denise@greenx.ie

CONSULTING EDITOR Ruth Morrow

SUB-EDITOR Emer Keogh emer@greenx.ie

CREATIVE DIRECTOR Laura Kenny laura@greenx.ie

ADVERTISEMENTS Graham Cooke graham@greenx.ie

WINTER VACCINES

Irish Osteoporosis Society’s annual Medical Conference 32

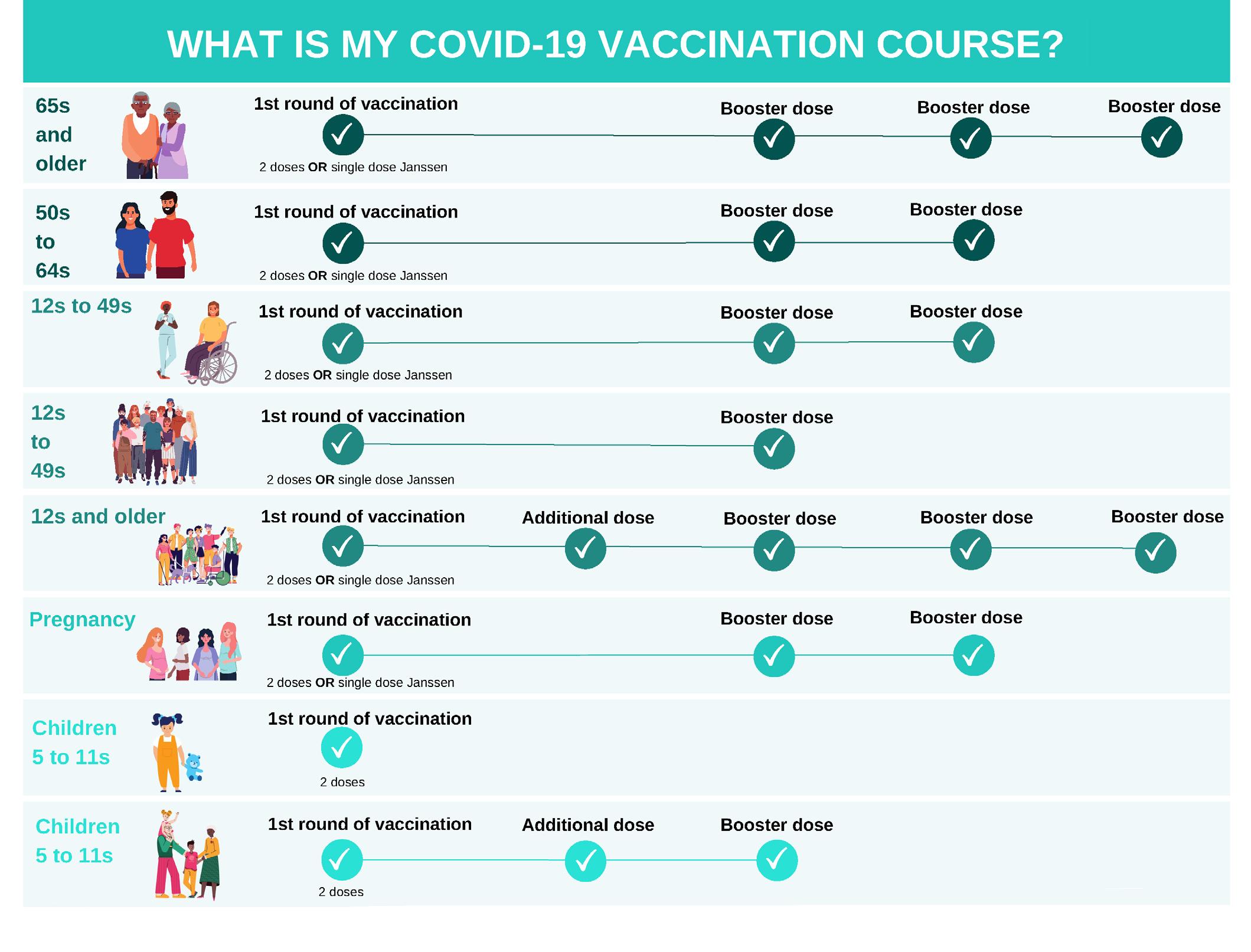

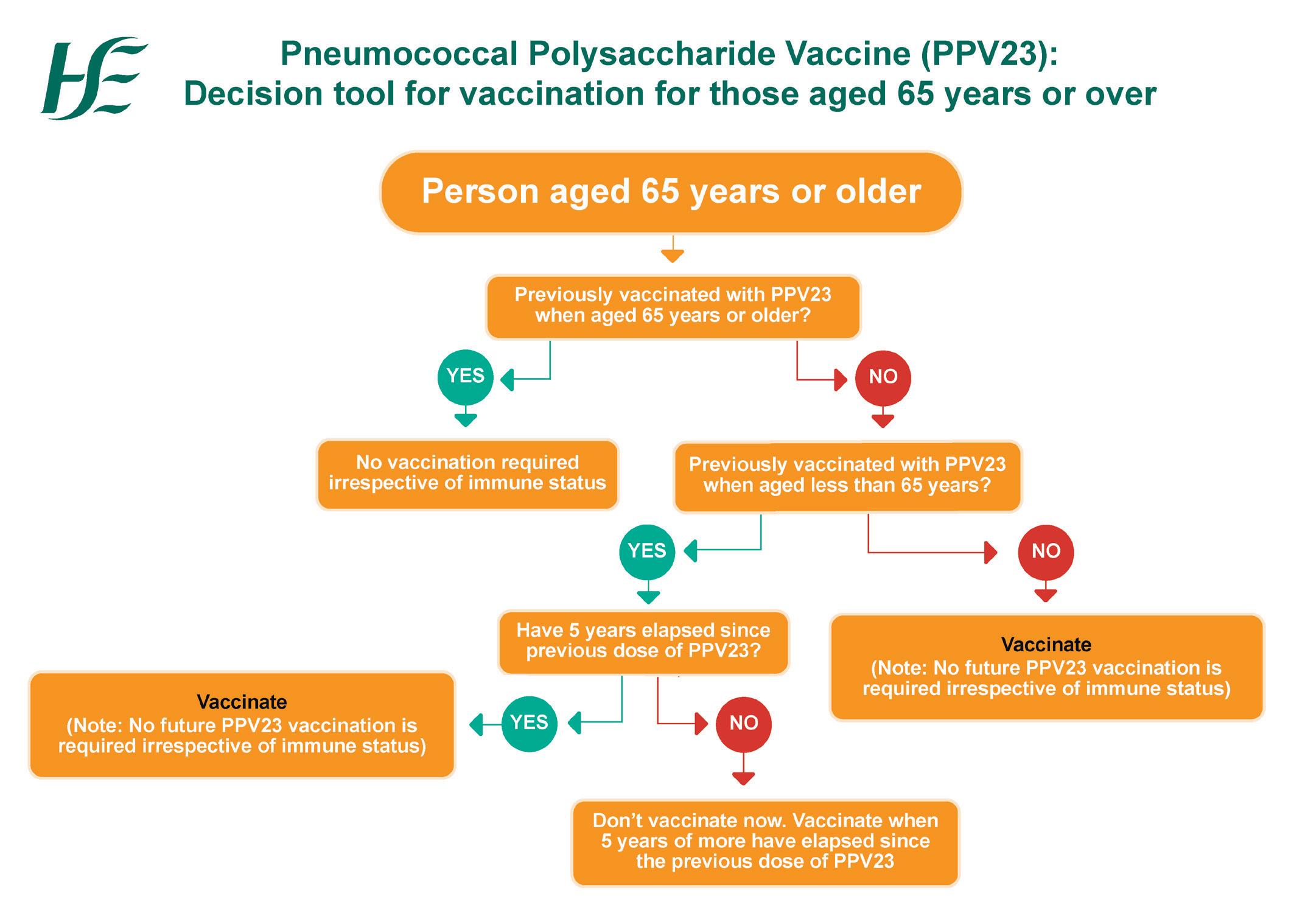

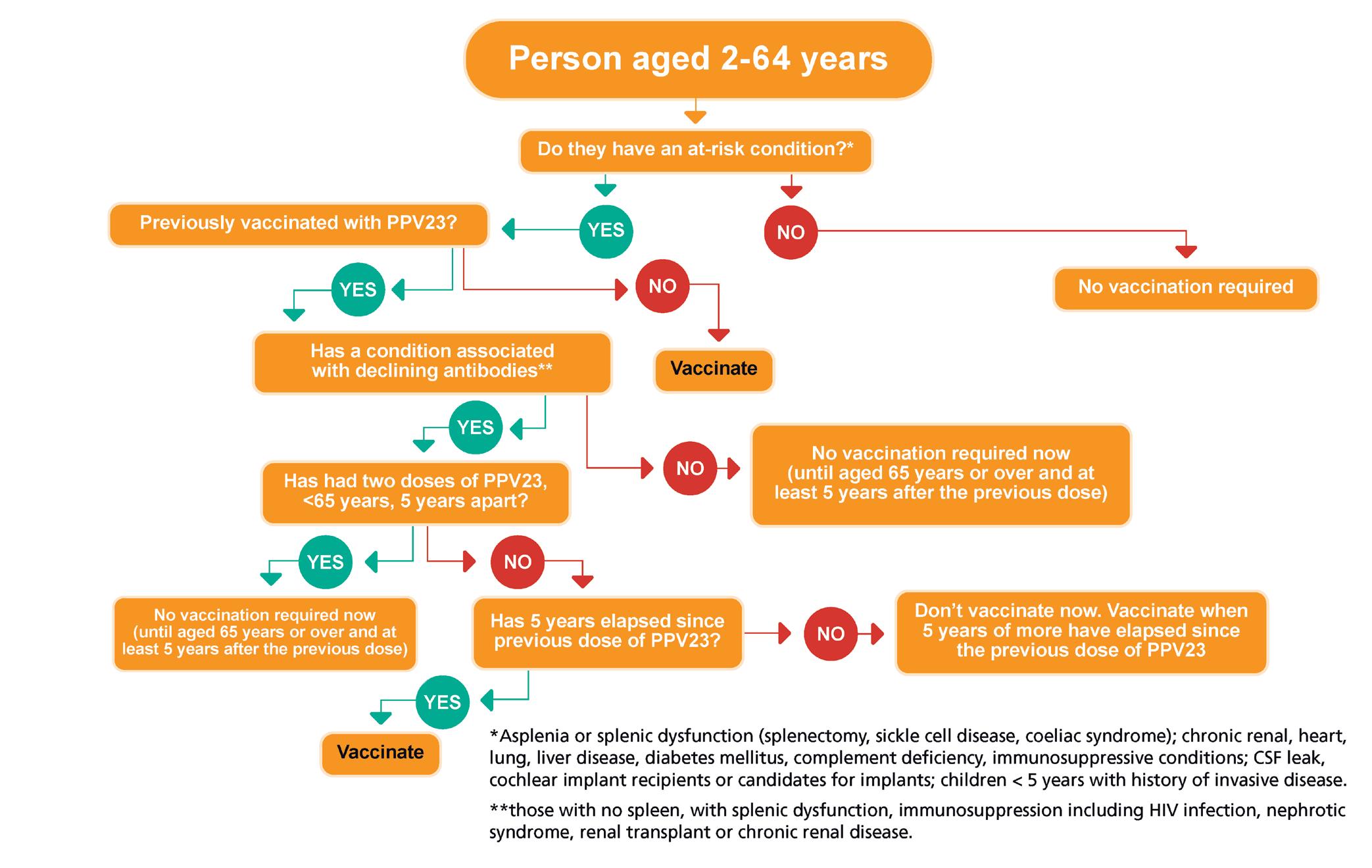

Vaccination updates for Covid-19 and flu from Dr Apama Keegan as the winter season approaches

MONKEYPOX Updates and recommendations for managing the current monkeypox outbreak by Dr Tom Barrett, Senior Medical Officer of the National Immunisation Office

ADMINISTRATION

Daiva Maciunaite daiva@greenx.ie

Please email editorial enquiries to Denise Doherty denise@greenx.ie

Nursing in General Practice is produced by GreenCross Publishing Ltd (est. 2007).

© Copyright GreenCross Publishing Ltd. 2022

Please email publishing enquiries to Publisher and Director, Graham Cooke graham@greenx.ie

TYPE 1 DIABETES Priscilla Lynch provides a comprehensive summary of the new NICE guidelines 48

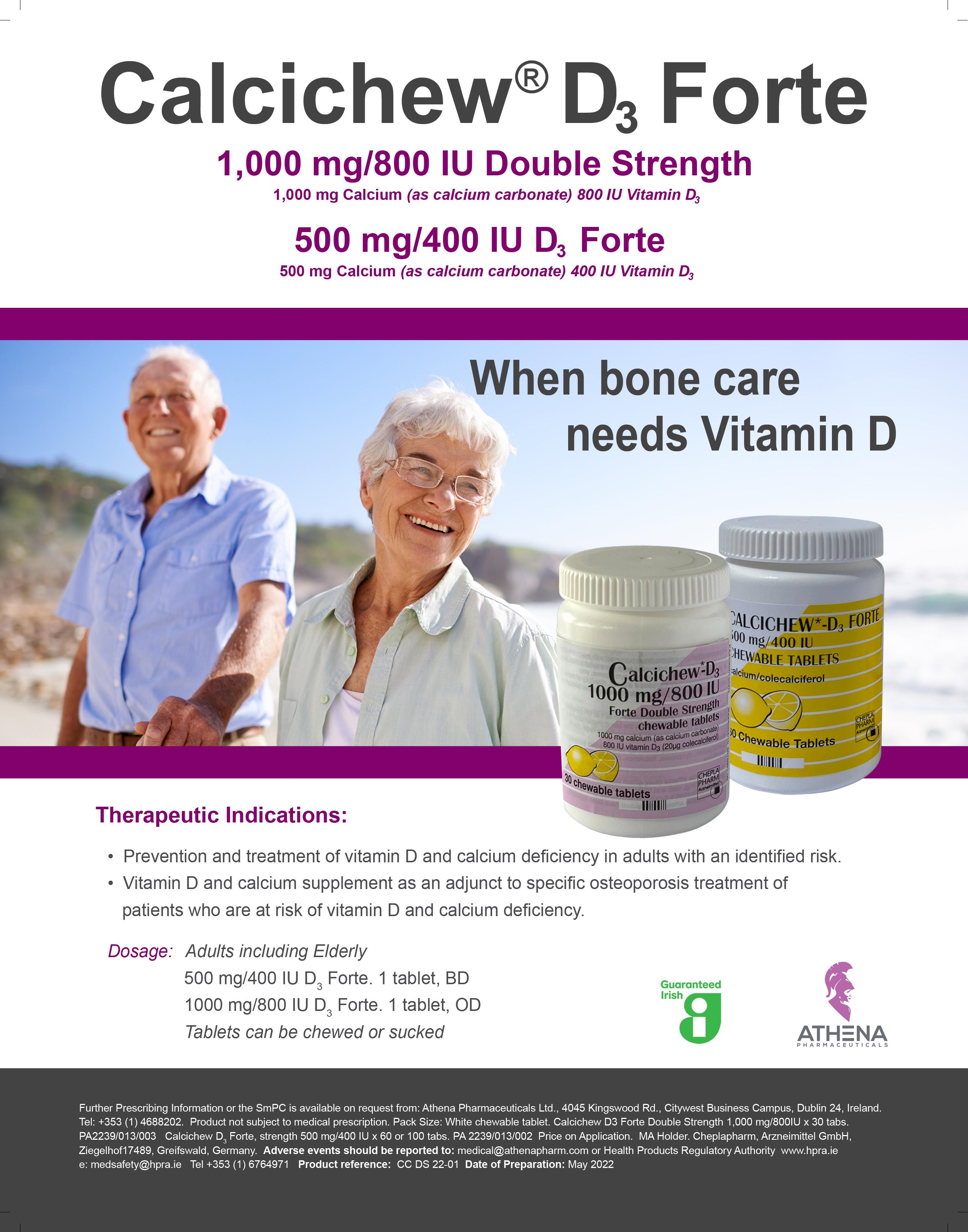

PRODUCT NEWS

The latest news in healthcare and pharmaceutical products

The contents of Nursing in General Practice are protected by copyright. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form by any means – electronic, mechanical or photocopy recording or otherwise –whole or in part, in any form whatsoever for advertising or promotional purposes without the prior written permission of the editor or publishers.

The views expressed in Nursing in General Practice are not necessarily those of the publishers, editor or editorial advisory board. While the publishers, editor, and editorial advisory board have taken every care with regard to accuracy of editorial and advertisement contributions, they cannot be held responsible for any errors or omissions contained.

Stroke is the second leading cause of death in middle to higher income countries and the leading cause of acquired adult neurological disability in Ireland. The HSE National Clinical Programme for Stroke marked World Stroke Day on 29 October by launching the new National Stroke Strategy 2022-2027. The programme has prioritised an ambitious, but realistic strategy, to improve resourcing of stroke services. It also seeks commitment from Government for a structured implementation, review, and a follow-on stroke strategy to commence in 2026.

The overall aim of the strategy is to achieve full realisation of the Stroke Action Plan for Europe by 2031. It also recognises the need for an all-age and complexitytiered approach to neuro-rehabilitation. The new strategy has identified four primary pillars of focus, primarily in view of the predicted increases in strokes in Ireland. They are:

1. Stroke prevention;

2. Acute care and cure;

3. Rehabilitation and restoration to living;

4. Education and research.

Stroke prevention highlights that strokes are preventable and that principal risk factors, such as hypertension and atrial fibrillation (AF), are also increasing. Key objectives for stroke prevention in the strategy include:

Develop a pathway for the case-finding, diagnosis, and treatment of high blood pressure in over 45-year-olds;

Develop a pathway for the prevention and case detection of AF;

Ensure all hospitals receiving acute stroke patients have a specialist-led, rapid access stroke service or access to such a service within their hospital network;

Ensure that all patients recovering from a stroke have access to a specialist secondary prevention stroke service and diagnostics.

Acute care objectives include:

Acute stroke services must have adequate staffing and diagnostic resources to provide 24/7 acute stroke care and treatment;

All hospitals receiving acute stroke patients must have an acute stroke unit;

Appropriate staffing of specialist stroke units with a number of trained physicians, nurses, healthcare assistants, health and social care professionals;

All patients must have 24/7 access to emergency acute stroke assessment and treatment by a stroke specialist.

Rehabilitation and restoration to living objectives include:

Early supported discharge teams to be fully commissioned across 21 high activity sites over a three-year period to cover 92 per cent of the stroke inpatient population; Stroke key worker resource to be appointed in each Community Health Organisation (CHO), so that discharged stroke patients and their families have access to the specific support and advice; All stroke patients to have a stroke passport (to contain information about their stroke, healthcare provider contacts, their condition, stroke medication, etc).

Education and Research objectives include: Funding for a sustained public awareness campaign on stroke; Creation of professorships in neurovascular and stroke medicine in six medical schools to improve Irish research and teaching in stroke;

Creation of three stroke research fellowships to enhance research and career opportunities and help retain our medical graduates in stroke medicine.

Dr Colm Henry, Chief Clinical Officer, HSE, said: “I welcome the launch of the new National Stroke Strategy, which has been developed to provide safe, effective stroke care with improved outcomes for patients. The strategy will bring stroke care in Ireland in line with other allied national strategies and the Stroke Action Plan for Europe 20182030 of the European Stroke Organisation. I am confident it will pay significant dividend for patients, healthcare, and society as a whole for years to come.”

The full document is available at: www. hse.ie/eng/services/publications/clinicalstrategy-and-programmes/national-strokestrategy-2022-2027.pdf.

Aglobal study, co-led by University of Galway, into causes of stroke has found that high and moderate alcohol consumption is associated with increased odds of stroke. The INTERSTROKE research looked at the alcohol consumption of almost 26,000 people worldwide, of which one-quarter were current drinkers and two-thirds abstained completely. The study included 12,913 cases of acute stroke from 27 countries with a diverse range of ethnic backgrounds. It also included 12,935 control participants. Countries where over 95 per cent of

the populations report never drinking alcohol, such as Pakistan, Kuwait, Iran, and Saudi Arabia were excluded.

Low alcohol intake was defined as one-seven drinks/week; Moderate alcohol intake was defined as seven-14 drinks/week for females and seven-21 drinks/week for males;

High intake was defined as >14 drinks/week for females and >21 drinks/week for males;

Heavy episodic (binge) drinking was defined as >5 drinks in one day, at least once a month.

Results: One-in-four people studied were current drinkers, one-in-six were

former drinkers, and the rest were never drinkers. In the study, those classified as current drinkers were linked with a 14 per cent increase in risk of all stroke and a 50 per cent increased risk of intracerebral haemorrhage. No increased risk of ischaemic stroke was noted in this group. Heavy episodic or binge drinking was linked with a 39 per cent increase in all stroke, a 29 per cent increase in ischaemic stroke, and a 76 per cent increase in intracerebral haemorrhage. High alcohol intake was associated with a 57 per cent increase in stroke. The study also found that there was no link between low level drinking and stroke.

Senior Lecturer at University College Cork’s (UCC) Department of General Practice and GP, Dr Tony Foley, has highlighted that there is no specific dementia training given to healthcare professionals in clinical practice, despite the prevalence of the disease. Around 25 per cent of all over 65-year-olds in hospital in Ireland have dementia or cognitive impairment and there are currently 64,000 people living with the disorder across the country. This figure is expected to reach 142,000 by 2050. In view of these figures, Dr Foley has called for an urgent, structured, pro-active model

of care for dementia patients, rather than a reactive approach, and advocates that dementia care become part of a National Structured Chronic Disease Management Programme in Ireland.

Dr Foley said: “The figures

for dementia are very high, not just here in Ireland, but across the globe. Dementia is now the second leading cause of death in the UK and Australia. It is one of the greatest health and social care challenges of our time. There

is an urgent need to act now to transform health, social, and palliative care services to meet the projected growth in palliative care needs.”

The GP and academic was speaking at a UCC Interprofessional Learning Workshop event, Understanding Dementia Together: A new collaborative multi-disciplinary approach, last month. The workshop is in its fourth year at the university, initially starting with occupational therapy and physiotherapy students, and expanding to include students from 11 different healthcare disciplines this year, ranging from nursing, to medicine, dentistry, pharmacy, and others.

The HSE National Forensic Mental Health Service (NFMHS) was officially opened on 4 November by the Minister for Health, Stephen Donnelly TD; Minister of State for Mental Health and Older People, Mary Butler TD; and Minister of State for Law Reform, James Browne TD. The relocation of the Central Mental Hospital (CMH) in Dundrum to the new, stateof-the-art, purpose-built facility in Portrane, Co Dublin, brings much anticipated and necessary reform to Ireland’s mental health services. This is the country’s largest capital project, costing in the region of €200 million.

Speaking at the opening, Stephen Mulvany, CEO, HSE said: “I am delighted to be here to mark this historic day. While the Dundrum site has a capacity of 96 patients, the National Forensic Mental Health Service increases that capacity to 110 beds initially, with a further expansion to 130 beds to occur in 2023. The opening of the Intensive Rehabilitation Care Units (ICRU) is also due to progress in 2023, treating 30 patients who require specific interventions, and will inform the strategic roll-out of a number of other facilities nationally.”

The new NFMHS will have the capacity to care for 170 patients on campus when fullyoperational. The facility also offers community and prison in-reach services, Forensic

Child and Adolescent Mental Health Service (FCAMHS), and an Intensive Care Rehabilitation Unit (ICRU) that will operate on site next year. NFMHS will also an additional five clusters of forensic mental health care, including a pre-discharge unit, female unit, mental health intellectual disability unit (MHID-F), high secure unit, and a medium secure unit.

The care and services that will now be more readily available to the most vulnerable and in-need populations, such as those engaged with prison, legal, and addiction services, was paid particular acknowledgement by several of the ministers present on the day. Minister Browne anticipates that the facility will enable more shared-care between services, and help many people towards the pathway to recovery and a subsequently improved qualityof-life. Minister for Justice, Helen McEntee TD, who was also present, echoed these sentiments and went on to

highlight that the new services would go beyond helping service users towards the path to recovery, but would also help to keep them there. She said: “We know that many of those who end up engaging with our criminal justice system have higher rates of mental health and addiction challenges than the rest of the population, and if we are to create safer communities and reduce crime, we have to ensure we have properly resourced, appropriately located systems of care in place for the most vulnerable people in society." Also present was Minister of State for Public Health, Wellbeing and National Drugs Strategy, Frank Feighan TD. He too made specific reference to vulnerable populations and the collaborative, multidisciplinary approach to their care that the new NFMHS would facilitate. He said: “People with severe mental health difficulties can also experience addiction issues, referred to as dual diagnosis."

The design concept for the

new facility is to support the underlying aim of providing therapeutic care and security with dignity, delivering a unique world class hospital that embodies the best principles of high secure mental healthcare design. 130 single patient bedrooms are laid out in small wards around shared indoor and outdoor spaces, in which collective activities and therapies take place. A ‘village centre’ provides shared recreational facilities, including a horticultural area, a gym, a woodwork workshop, and a music room, while a series of courtyards and secure perimeter gardens allow patients direct access to nature from each ward. The village centre also houses mental health therapeutic services, a GP and a dentist.

The new facility will also: Ensure that patients are living in accommodation appropriate to their needs, risks and modern healthcare standards; Improve the quality-of-life of the patients and carers using the services;

Increase the number of high and medium secure beds in accordance with international comparisons and national need;

Deliver specialist secure care for MHID-F and CAMH-F patients;

Reduce the operating costs of the service pro rata;

Modernise and improve clinical practice;

Reduce costs to the HSE for placement of patients in the UK, prisons and other HSE services.

Patrick Bergin, Head of Service at NFMHS, described the opening as a welcome day for patients and “a key milestone in the delivery of a modern forensic service to our patients”. He went on to say: “We now have the opportunity to be a centre of excellence and evolve our delivery of treatment and care… and this new facility provides us with opportunities to be a world leader in this specialist field.”

The state-of-the-art centre doesn’t just promote a holistic and individualised approach to mental health, but also takes measures to improve planetary health as well. Eight hectares of new native woodland will be established as part of the project and up to 20,000 trees will be planted; 2000 of which will be certified Irish native trees. The new development is also responsible for improving and diversifying adjacent

wetland habitats, including opening up and reprofiling drainage ditches, and creating new ponds and wader habitats within the wetlands. Landscaping within the grounds of the new hospital includes substantial pollinator friendly planting that will provide foraging for a variety of nectar feeding invertebrates including butterflies, moths and hoverflies, and a large wildflower meadow.

Minister Butler thanked

those involved in the project and commended the new services and the positive impacts they will have. She said: “I welcome the opening of today’s new complex, which will enable the HSE to support the enhanced delivery of person-centred care, underpinned by human rights for persons using the service and their families. This is one of the most modern forensic mental health facilities in Europe."

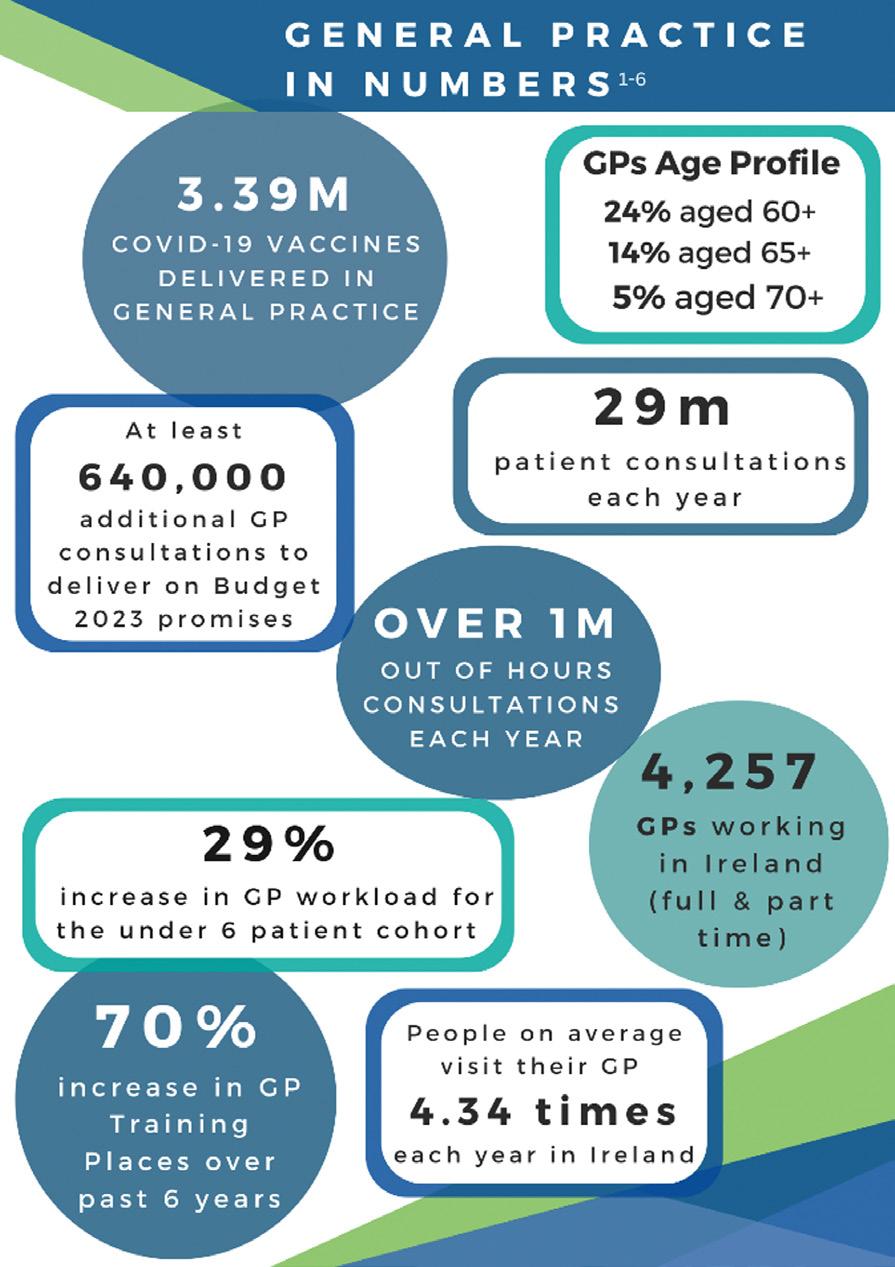

The Irish College of General Practitioners (ICGP) has proposed 10 potential solutions to the growing shortage of GPs in Ireland, and the subsequent issues this is causing that we outlined in the previous issue of NiGP. The solutions are part of the ICGP’s comprehensive Discussion Paper Shaping the Future of General Practice that was launched at their Autumn conference last month. The 10 proposed solutions outlined in the document are:

1. Expand GP-led multidisciplinary teams;

2. At least double the number of GP practice nurses;

3. Resource the career expectations of future GPs;

4. Provide suitable premises for GP-led multidisciplinary teams;

5. Fast-track suitably-qualified GPs to take on GMS lists;

6. Increase remote consulting;

7. Introduce a career pipeline for

rural general practice;

8. Develop the role of practice manager;

9. Increase exposure to general practice in medical schools;

10. Invest in GP data-informatics to drive policy and practice.

Prof Tom O’Dowd, former ICGP President and GP in Tallaght, chaired the ICGP group which produced the paper. He said: “We propose solutions in this paper, but it is the key stakeholders working collectively that will help produce the solutions. This is an urgent problem that cannot be solved overnight, and while we welcome the Minister’s decision to establish a strategic review of general practice, we urge the Minister to act immediately and to begin the process of finding innovative solutions to this crisis. This review and establishment of a working group is needed as a matter of urgency if the extension of free GP care is to proceed.”

The Irish College of General Practitioners (ICGP) has launched its Quick Reference Guide on Menopause, which is now available for its members to access.

The guide is designed to assist GPs and practice nurses in the management of menopause and its myriad symptoms through evidence-based interventions.

Last month, the Minister for Health, Stephen Donnelly TD, launched a government awareness campaign for menopause as a direct response to the demand from Irish women for greater knowledge and understanding of the major life event. They want better access to accurate information and supports, so that they can proactively manage their experience and maintain a high quality-of-life during it. The campaign is intended to meet their demands by increasing awareness of and encouraging open conversation about menopause, its symptoms, and associated stigma.

Welcoming the launch of the Quick Reference Guide on Menopause, Minister Donnelly said: "When launching the Women's Health Action Plan in March 2022, I committed to changing the approach to menopause care in Ireland,

and increasing the supports available to women before, during and after menopause. Women told us they needed more when it came to support and treatment for this significant life event. We have been responding to this ask, for example, through the development of specialised menopause clinics nationally, and today, the ICGP has responded by publishing this reference guide, which will assist GPs across the country in treating people experiencing menopause."

As well as the new guide for ICGP members, the College has also published a series of online videos about the menopause to help educate and guide the general public, as well as increase awareness. These online resources have been created by the ICGP’s Director of Women’s Health, Dr Nóirín O’Herlihy, and the ICGP’s GP Clinical Lead in Women’s Health, Dr Ciara McCarthy. The five short videos are designed to provide some general information about menopause, what it is, how it is diagnosed, and what to expect from its treatment.

Speaking about the new ICGP guide, Dr McCarthy said: "Menopause is a major life event affecting all women in a variety of ways, with up to 80 per cent

of women experiencing physical and/ or emotional symptoms during that time. Most of these symptoms can be managed in general practice and this guide comprises evidence-based information on the management of perimenopause and menopause in general practice by GPs and practice nurses. It provides advice on diagnosis, lifestyle interventions, prescribing HRT safely, alternative options to HRT, and specific advice for women with a history of breast cancer. An overview of the management of premature ovarian failure is included." Dr O'Herlihy, added: "This reference guide is a significant milestone in the care of women with perimenopause and menopause in Ireland and part of the widening of knowledge and understanding. It is funded by the Women's Health Taskforce and the National Women and Infants Programme, and will provide GPs with updated and comprehensive knowledge on menopause treatment for their patients."

The Quick Reference Guide on Menopause is available for ICGP members at www.icgp.ie/MenopauseQRG.

The series of public videos about the menopause is available at www.icgpnews. ie/menopause-patient-information/.

Nurses and midwives employed by the public service have accepted the proposals in the review of Building Momentum by 97 per cent. Included in the review, as outlined in the previous issue of Nursing in General Practice, are a 3 per cent increase on

annualised salary to be back paid in February 2023; a further 2 per cent increase on annualised salary from 1 March 2023; and a 1.5 per cent increase (or €750, whichever is the greater) from 1 October next year. This is in addition to the 1 per cent (or €500 increase if greater) due to members from 1 October

2022, as previously agreed. Nurse manager grades were notified this week that the circular to apply the 3.28 per cent increase from February 1 2022 has been issued.

The INMO has written to the HSE to confirm that these payments will be made urgently.

As the winter arrives, bringing with it the associated demands and strains on the health services, the HSE has outlined actions that will be taken to support the sector and manage the expected increase in the number of patients requiring care over the coming months. 2022 has already seen a 5.36 per cent increase in overall attendances to the emergency department (ED); a 0.74 per cent increase in hospital admissions; and a 12.92 per cent increase in ED attendances by those aged over 75 years, when compared to 2019. Funding of just over €169 million has been assigned to implement the measures outlined in the Winter Plan, which will include the recruitment of 608 posts across a range of services and the vaccination programme for influenza and Covid-19.

Speaking about the plan, Chief Clinical Officer of the HSE, Dr Colm Henry, outlined how our third winter with Covid-19, alongside other seasonal viruses, carries much uncertainty, and has the potential to add substantial pressure on our already strained services. He said: “Our response has been to create additional much-needed capacity and to diversify access to healthcare and reduce reliance on hospitals. While these measures are all necessary and helpful, we can all act an individual level to reduce the impact of Covid-19 and influenza by getting our winter vaccines as soon as possible.”

Major actions outlined in the plan include: Delivering additional capacity in acute and community services. This will include the ongoing delivery of additional acute and community beds and increasing staffing capacity in line with the Safe Staffing and Skill-Mix Framework. The HSE also plans to extend the opening hours of a number of local injury units during the winter period.

Improving pathways of care for patients: Alternative patient pathways will be implemented during the winter period to help reduce the number of presentations and admissions to hospital and improve patient flow and discharge. This includes enhanced community care (ECC) supports.

Roll-out of the vaccination programme: The influenza and Covid-19 vaccination programmes continue to be rolled out. Targeted communications will be used to increase awareness and uptake for winter vaccine programmes.

Implementation of the Pandemic Preparedness Plan: The Public Health Plan will be implemented as appropriate, which includes a surge and emergency response plan, in the event of a significant surge in Covid-19 infections.

Mary Day, HSE National Director for Acute Operations acknowledged the progress and investment and also the persistent challenges faced in healthcare. She said: “No matter what the time of year, HSE services are seeing and treating more patients in hospitals and in the community than ever before. In our acute hospitals this year, over 1.6 million people will have an inpatient or day case procedure or use maternity services. We have also provided 14.2 million home support hours this year to date to enable people to remain at home and to support their families to care for them.”

Yvonne O'Neill, HSE National Director for Community Operations added: “The fact that we are continuously growing the amount of healthcare provided to the population is good news, but the growing demand also results in delays and waiting lists, and the measures being announced today will go some way to easing that in what may be a very busy period.”

Some of these additional measures in the plan include:

A further €4.5 million for aids and appliances to enable patients be discharged home or to a community facility as quickly as possible.

Expansion of patient flow and discharge teams in hospitals and community to minimise delays in discharge or transfer to other hospitals or step-down facilities.

Additional funding for complex care packages, which will enable hospitals to discharge patients with complex need by giving them the supports they need to be cared for at home.

Extra funding to allow treatment of more patients in the private hospital system.

Funding for additional access to diagnostics for GPs to enable them to refer patients directly for x-rays or scans, rather than it being necessary for them to be sent to EDs in order to access such diagnostic services. Over 188,516 scans have been completed as part of the GP access to diagnostics initiative so far this year.

Additional funding to the GP out-of-hours service, including expansion to provide full coverage in rural areas in Community Healthcare Organisation (CHO) West.

Investment to support expansion of Community Intervention Teams (CIT) across the country with a particular focus on the Mid-West and North-West regions.

Funding to enhance palliative care services during the winter, which will deliver 1,340 nights of night nursing to 380 patients and families.

Funding has been provided for an integrated action team funds, which each Hospital Group and CHO can request access for specific initiatives during the winter period.

Reinforcement of the key role of Covid-19 and flu vaccines in reducing the level of severe respiratory illness

The full plan is available at : www.hse. ie/eng/services/news/media/pressrel/ winter-plan-2022-23.pdf.

The Institute of Public Health (IPH) has launched a free digital learning course to help healthcare professionals support older people towards achieving and maintaining the recommended 150+ minutes of physical activity per week. The new Getting Active for Better Ageing course is part of the IPH’s ongoing Public Health Matters programme, which continues to create and provide digital resources to help promote and improve public health. The online modules and courses are suitable for the public, as well as healthcare professionals and policy makers. Both the platform and app are regularly updated to include new podcast episodes, blogs, videos, and other content and resources relevant to many aspects of public health.

This latest course was developed following research findings published by the IPH in 2021 that identified the need for

tailored education, training, and resources to support healthcare professionals to promote physical activity in routine practice. Getting Active for Better Ageing is available on the IPH’s Public Health Matters app or desktop platform. The resource is aimed at general practice nurses (GPNs), GPs, physiotherapists and all healthcare professionals that interact with older adults. It is also suitable for carers and members of the public with an interest in

promoting and supporting activity in older age. The new resource sets out key facts, guidelines, and tools on how to support behaviour change in older adults, as well as other essential information.

IPH Director of Ageing Research and Development Prof Roger O’Sullivan said: “The evidence is clear, physical activity plays an important role in our health at all stages of life, including in older age, which is sometimes overlooked. This new free learning resource is available on our Public Health Matters platform and was developed as a practical programme to assist healthcare professionals to support older persons to be more physically active.”

You can access the Public Health Matters desktop platform at: https://learning.publichealth.ie/ or you can download the Public Health Matters app for free on the Google Play (Android) and iTunes store (Apple).

GP practice nurse required in friendly practice in Rathfarnham

12 hours per week over 3 sessions

l To work alongside other full-time practice nurse

l Previous experience desirable but not essential

l Training provided l Good location l Modern bright purpose-built premises l Free parking

Duties to include, but not exclusive to: Phlebotomy, ear syringing, childhood vaccines and other immunisations, smear taking, chronic disease management, ECG, 24 hour ABPM, removal of sutures/ wound dressings, diabetes, assist with minor procedures, telephone triage, Covid/flu vaccinations.

Please send CV to practice manager Grace: gablesmedc@gmail.com

Practice nurse required in Ballinteer, Dublin 16 (just off M50) from 01/02/2023.

Busy 1 (full-time male) GP +2 (part-time female) GP practice.

At least 5 (3 hour) sessions, some flexibility with day mornings/afternoons.

Experience in phlebotomy, childhood immunisations and cervical smear taking is necessary.

Experience in antenatal care, BP monitoring, chronic disease management an advantage. Very nice family orientated type practice.

Please contact 086 8132303 (text) or email drmaevemoloney@gmail.com for further information.

If you would like to place a recruitment advert in the next edition, please contact Louis@mindo.ie

Helps rebalance the gut microbiota1 4 to support immune development and long-term health5-8

IMPORTANT NOTICE: Breastfeeding is best. Neocate Syneo is a food for special medical purposes for the dietary management of Cow’s Milk Allergy, Multiple Food Protein Allergies and other conditions where an amino acid based formula is recommended. It should only be used under medical supervision, after full consideration of the feeding options available including breastfeeding. Suitable for use as the sole source of nutrition for infants under one year of age. Refer to label for details. 1. Burks AW et al. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2015 Mar 31; 26(4):316–322. 2. Candy DCA, et al. Pediatr Res. 2018 Dec 6; 83(3):677-686. 3. Fox A.T, et al. Clin. Transl. Allergy. 2019 Jan15; 9.5 4. Chatchatee P, et al. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2021 Jul 2; S0091-6749(21)01053-8. 5. Martin R et al. Benef Microbes. 2010. 1(4):367–82. 6. Wopereis H et al. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2014. 25:428–38. 7. West CE et al. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 135(1):3–13. 8. Walker WA et al. Pediatr Res. 2015. 77(1):220–228. 9. Sorensen K, et al. Nutrients. 2021 Mar 14; 13(3):935. 10. Sorensen K, et al. Nutrients. 2021 Jun 27; 13(7):2205. ± Exploratory outcomes from randomised control trials, Neocate Syneo vs Neocate LCP; † Systematic review of 4 randomised controlled trials, Neocate Syneo vs Neocate LCP. ¥ UK Observational study of real world evidence in THIN GP database, Neocate Syneo vs Alfamino, Feb 2021 (Alfamino is not currently GMS listed in ROI); ^ Clinical journey: asymptomatic and not requiring hypoallergenic formula prescription for at least 3 months. § Product can be provided to patients upon the request of a healthcare professional. They are intended for the purpose of professional evaluation only. Nutricia Ireland, Block 1 Deansgrange Business Park, Deansgrange, Co. Dublin. Date of publication: 02/2022

Just over two years ago, Geraldine Mullan’s six-yearold daughter Amelia explained that her little heart had four corners; one for her, one for her older brother, one for her mammy, and one for her daddy. Only months later, Geraldine’s own heart would be irreparably broken, and three of its four corners would be left empty.

On 20 August 2020, she was the sole survivor of a car accident that claimed the lives of her beloved husband, John, and their children, Tomás (14) and Amelia (6). Since then, the devastated Oncology Nurse Specialist has worked tirelessly to keep their memory alive and to spread a little hope through her local community.

Speaking to Nursing in General Practice (NiGP), Geraldine describes the horrific event that took those she loved most and its aftermath. She and her family were returning home to Moville in Co Donegal after what she now describes as “a very precious family day” at the cinema complex in Derry that night, busy making plans for going back to school and enjoying each other’s company. The weather was particularly aggressive that evening, with violent waves and winds lashing the Inishowen Peninsula. Geraldine tells NiGP how she vividly remembers

THE VIBRANT SPACE HAS BECOME A HUB FOR LOCAL FAMILIES, VISITORS, AND MANY OF TOMÁS AND AMELIA’S FRIENDS

every single second and detail of the horrendous few minutes that changed her life forever. She doesn’t elaborate and doesn’t need to, as words simply don’t exist to describe the horror.

While words fail, Geraldine’s strength, determination, and generosity since the tragedy have not, despite the infinite grief she is left with. Her mission since burying her family is to keep their memory alive and to give back to the local community that she says has been a rock to her throughout the trauma. Originally from Galway, Geraldine now considers herself a local in Inishowen and describes the overwhelming support she received, and continues to receive from those around her. Geraldine was nominated by that very community for the national Goss.ie Local Hero Award 2022, and has been hailed as an inspiration in the area for her work since the tragedy.

Instead of watching John’s much loved garden centre close after his death, his wife has transformed it into the Mullan HOPE Centre in his and their children’s memory. The vibrant space has become a hub for local families, visitors, and many of Tomás and Amelia’s friends. Geraldine has dedicated herself to creating a place that oozes joy, hope and love, where families can enjoy precious time together and make memories like those that now help her get out of bed each morning. “I won’t see my own children grow up, but I will see their friends having fun and getting older,” Geraldine smiles sadly as she describes the sense of comfort she gets from being with those who were close to her family. “My memories are what keep me going. I love to see their friends having fun and smiling. I know they are still with me and I can hear John telling me to keep going. He was a wonderful, supportive husband and I was so blessed to have had the time we shared with our beautiful children. Sometimes I live day-by-day,

others it's hour-by-hour, and on the very bad days, it’s a minute at a time. They [John, Tomás and Amelia] give me strength. They say grief is the price we pay for love. There was a lot of love.”

The pictures that hang in every corner of the Mullan HOPE Centre reflect a family that indeed radiated love and hope, and that is what Geraldine is determined to keep alive in their memory. She is busy organising the Christmas markets that will be hosted at the centre next month, after welcoming hundreds of dressed-up children and their families for a hugely successful ‘Spooktacular Farmers Market’ over Halloween. During the summer, Geraldine spread her message of hope to thousands when she created the Field of Hope, a two-and-a-halfacre field of fabulous sunflowers that she nurtured herself, again, with some extra help from those around

her. Seeds from a sunflower grown by little Amelia were among those sown in the field. She and Tomás had been growing the flowers to enter a competition with the help of John, the garden centre expert. “Sunflowers were Amelia’s favourite,” Geraldine explains with a smile as she remembers. The project literally evolved to scream hope, when a maze was carved out within the plantation in the shape of the letters H-O-P-E. At the end of August last year, to mark the second anniversary of the accident, Geraldine opened the field to the public. Over 15,000 people from all over the country visited the sea of gold that stretched towards the sky in memory of her family, in the name of hope, and in solidarity with others that had experienced loss.

The Mullan HOPE Centre and Geraldine’s impact on the local area led to her nomination for ‘Local Hero’ at this year’s Goss.ie Women of the Year Awards. Geraldine, who also recently won Community Champion of the Year at the Derry Journal People of the Year Awards, and RSVP ’s Unsung Hero Award, was named the overall winner at a ceremony hosted by Gráinne Seoige at the Royal Marine Hotel in Dun Laoghaire last month. “I’m humbled,” Geraldine says and bows her head. “I am very grateful, but I just want to share some hope. It’s all I have and sharing it and the memory of John, Tomás, and Amelia is what keeps me going. I just hope that our story can bring a little hope to those that need it most.”

Geraldine continues to work as an Oncology Nurse Specialist in Letterkenny University Hospital and describes it as the place she can just be Geraldine, and not the woman who lost everything she loved most in the world. Her job is also a huge support structure and she intends to keep practising, and to continue to host events for her community for as long as she can in memory of her beloved family. l

SOMETIMES I LIVE DAY-BY-DAY, OTHERS IT'S HOUR-BY-HOUR, AND ON THE VERY BAD DAYS, IT’S A MINUTE AT A TIME

Iron deficiency and anaemia are two significant comorbidities that are present in a large proportion of cardiology patients.1,2 Iron deficiency is a well-recognised cardiovascular risk factor in heart failure,3,4 with the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) recommending parenteral iron replacement as part of standard care for chronic heart failure patients that are found to be iron deficient (Class IIa recommendation, Level of Evidence: A).5

There is a growing hypothesis that iron deficiency may have a significant impact on cardiovascular health at all levels and conditions, and that replenishment may also be of benefit to the general cardiovascular disease population.

Iron deficiency can be classed as either absolute iron deficiency (AID), or functional iron deficiency (FID). AID is defined as serum ferritin <100μg/L, with FID defined as a combination of serum ferritin <100-300μg/L in combination with a transferrin saturation (TSAT) <20 per cent.

This article will discuss the significance of iron deficiency in cardiology patients, the available evidence relating to iron deficiency in these patients, and the recommendations from current guidelines. It will also discuss anaemia due to its close association with iron deficiency.

The causes of iron deficiency and anaemia are often multifactorial. Nutritional deficiency, chronic inflammation, blood loss, and unexplained presentations are common causes within the general population. 2 The causes of iron deficiency and anaemia in the cardiology patient cohort may be due to their cardiac condition,

pass through or around a prosthetic valve; including transcatheter aortic valve implantations (TAVI). This can also occur in the setting of a severely stenotic native aortic valve and may be exacerbated when combined with small bowel angiodysplasia, which will result in slow, often difficult to localise, gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding, known as Heyde’s syndrome. Heyde’s syndrome is due to von Willebrand

their comorbidities, or their medication. Cardiac conditions themselves can lead to, or exacerbate, both iron deficiency and anaemia. Chronic heart failure causes chronic inflammation, as well as hypervolaemia, both of which can affect gut absorption of dietary iron, exacerbating anaemia. Patients with valvular heart disease can often be anaemic and/or iron deficient too.6 Microangiopathic haemolytic anaemia (MAHA) is a non-immune haemolysis often caused by intravascular blood cell fragmentation as the red cells

factor destruction as it passes through the valve, with subsequent abnormal clotting and spontaneous GI bleeding, in comparison to the intravascular haemolysis of MAHA.

Infective endocarditis (IE) persists as a significant, critical illness in the cardiology population with valvular dysfunction, which may lead to anaemia, as outlined above. Subacute IE results in profound chronic inflammation and patients often present with anaemia due to their diseased valve and their chronic inflammatory state.7 Many cardiology

INFECTIVE ENDOCARDITIS (IE) PERSISTS AS A SIGNIFICANT, CRITICAL ILLNESS IN THE CARDIOLOGY POPULATION WITH VALVULAR DYSFUNCTION, WHICH MAY LEAD TO ANAEMIA

patients have concurrent chronic renal disease, which can result in reduced erythropoietin production and anaemia at a bone marrow level.

With regards to medication in the cardiology population, both antiplatelet and anticoagulation agents are associated with increased bleeding and subsequent anaemia risks, especially GI bleeding. These are used ubiquitously in the cardiology population, for primary and secondary prevention of coronary artery disease (CAD) and arrhythmias. Stress ulceration of the GI tract, in the setting of acute coronary syndrome, can often contribute to this, which has been recognised since the 1940s. 8 Previous studies also suggest other drug-induced causes, such as angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) that reduce haemoglobin levels via reninangiotensin system inhibition. 9 Finally, in relation to patients with IE, prolonged parenteral antimicrobial therapy can contribute to anaemia, with some classes of antibiotics causing haemolytic anaemia or myelosuppression.

Most of the available evidence regarding the role of iron deficiency and anaemia in cardiology is in association with heart failure. Both iron deficiency and anaemia are independently associated with poor outcomes in heart failure.6

In patients with iron deficiency without anaemia, there is reduced uptake of iron by non-erythroid tissues and bone marrow. Within these nonerythroid tissues, iron has multiple key roles because of its ability to bind oxygen. As a result, it is required in metabolic cellular reactions, such as oxidative phosphorylation and production of reactive oxygen species (ROS).10 Iron acts as an electron transporter in sites of oxygen utilization, including the mitochondria, that are abundant in high-energy areas, such as skeletal muscle or cardiac myocytes. Mitochondrial function relies

on iron homeostasis.11

Mitochondrial failure due to iron deficiency leads to cellular anaerobic metabolism, resulting in less effective cellular energy production. In mouse models, disruption of this pathway, forcing anaerobic metabolism, resulted in a severe form of cardiomyopathy and resultant death within 14 days.12 Anaemia results in reduced oxygen delivery to tissues, leading to increased workload, causing left ventricular hypertrophy and remodelling; worsening the oxygen demand present prior to this. Groenveld et al (2008) concluded that anaemia doubled the relative risk of death in a meta-analysis of 150,000 patients across 33 studies. 13

Iron replacement as a treatment option for iron deficiency, with or without anaemia, has been used for many years in both primary and secondary care. Oral iron replacement is often the initial treatment of choice, however, there is evidence that it is relatively unsuccessful at replenishing iron stores. IRONOUT-HF was a large double blinded, randomised, placebo-controlled trial of 225 heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) patients, with AID or FID, treated with oral iron replacement for 16 weeks. Peak oxygen update (VO 2 Max) did not change during cardiopulmonary exercise testing, nor did the six-minute walk test (6MWT) results, or NT-proBNP levels. 14 Oral iron replacement can also cause significant adverse GI effects, including constipation, nausea, and dark stool. 40 per cent of patients in IRONOUT-HF experienced such issues.

Parenteral/Intravenous (IV) iron replacement is available in several formulations. Compliance, tolerance and absorption are all superior in the IV route compared to the oral route.

Iron formulations include, but are not limited to, ferric carboxymaltose (FCM) (Ferinject), ferric sucrose (Venofer), ferric dextran (Cosmofer) and ferric derisomaltose (Monover). Previous clinical trials regarding iron replacement in heart failure have primarily used FCM.

Parenteral iron replenishment is generally given in secondary care in Ireland due to administration and monitoring requirements during infusions. IV iron usually requires multiple doses as well as the potential for maintenance treatment, therefore, proper organisational and infrastructural support is required for treating large numbers of patients. This generally includes administrative and specialist nursing support, which is more readily available in acute hospital settings, but it is anticipated that this could be transitioned to more community-based care in the future.

IV FCM, as the most evidencebased formulation, is generally administered up to 1g as an infusion over 15-30minutes. Infusion reactions are common and in the region of 10 per cent. These include infusion site irritation, extravasation, rash, dizziness, and a range of hypersensitivity/ allergy symptoms that can reach lifethreatening anaphylaxis. More severe reactions were previously more common with early-generation IV iron, but have become less common as modern variations are generally better tolerated. Patients with an allergy to a single formulation are often able to tolerate different formulations, but caution should be advised with subsequent administrations of same.

Blood transfusion is frequently used in an acute setting to treat severe anaemia. Packed red blood cells, although a reliable source of iron, are a scarce commodity and have risks of transfusion-associated side-effects or reactions. Research advocates for restrictive use of transfusion in

hospitalisations after acute myocardial infarction (MI), 15 and transfusion is not recommended routinely in the management of chronic cardiovascular conditions in isolation, unless indicated for other reasons.

Chronic renal disease, with resultant relative erythropoietin deficiency, can contribute to anaemia in heart failure. Erythropoietin stimulating agents (ESAs) have been successfully used in renal disease, where there is a benefit in avoiding blood transfusions. However, RED-HF16 failed to show significant clinical benefit of ESAs for patients with systolic heart failure and haemoglobin of 9-12 g/dL. In fact, increased risks of thromboembolic events and strokes resulted in worse clinical outcomes in this cohort.

FAIR-HF (Ferric Carboxymaltose in Patients with Heart Failure and Iron Deficiency) 17 was the initial trial investigating iron replacement in chronic heart failure patients, with or without anaemia. The trial included 459 patients. Dosage was dependent on participant weight and haemoglobin level at screening, with weekly administration until repletion, with four weekly maintenance infusions. Whilst there was no significant effect on all-cause mortality, there was improvements in New York Heart Association (NYHA) class and outcomes scores.

CONFIRM-HF18 was designed similarly to FAIR-HF. 6MWT (10 endpoint) was significantly improved (33m +/- 11m) after IV iron. Patients were treated for longer (one year vs six months) and received higher dosages than the FAIR-HF population. Secondary endpoints also showed improvement including NYHA levels and patient global assessment scores.

Primarily, both trials confirmed iron replacement was associated with improved functional capacity and quality-of-life. However, neither trial identified a mortality benefit. CONFIRM-HF did show a reduction in heart failure hospitalisation, but this was on post-hoc analysis alone and the trial was not designed or powered for this hypothesis. Metaanalyses of available studies identified that FCM infusion significantly reduces hospitalisation, heart failure hospitalisations and overall mortality (RR 0.59; p = 0.009). 19

Three trials are currently underway which are powered for the primary endpoint of heart failure hospitalisation or cardiovascular death in patients with HFrEF and iron deficiency. IRON-MAN is the first trial to assess with intravenous ferric derisomaltose. FAIR-HF2 is the subsequent trial from FAIR-HF, again using ferric carboxymaltose. Meanwhile, HEART-FID is designed to assess the effects of ferric carboxymaltose on all cause death, heart failure hospitalisation, and 6MWT improvement.

At the time of writing, a randomised control trial (RCT) assessing the role of parenteral iron replenishment in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) has not been published, however, FAIRHFpEF should answer that question. Our knowledge in HFpEF relies on systematic reviews and metaanalyses of HFpEF/iron deficiency that demonstrate negative impacts on NYHA, 6MWT, and quality-of-life measures. From this, we infer that iron deficiency has an important role in HFpEF, as in HFrEF. It is hypothesised that these patients may benefit from IV iron, however, clear evidence in the form of an RCT will confirm this.

Although most previous research on the impact of iron deficiency in the cardiology population has been in heart failure, iron deficiency, with

or without anaemia, has been linked to several other cardiac pathologies. These include CAD, arrhythmia, and major adverse cardiac events (MACE).

Iron deficiency is present at high rates among patients with atrial fibrillation (AF), as observed in several small studies. Larger studies are ongoing to confirm these observations. IRON-AF is currently assessing the impact of iron infusion in patients with AF. This initial short trial (12 week followup) will assess peak oxygen uptake, similar to initial HF trials. Secondary outcomes being examined include transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) parameters, AF burden via quality-oflife (QoL), Holter, and death.

It has been highlighted in several landmark trials that anaemia is associated with worse cardiovascular outcomes. When patients were followed for four years, a 1g/ dL decrease in haemoglobin was associated with an increased relative risk of cardiovascular death (RR=1.28) and MACE events (RR=1.23), 20 whilst a 14,000 patient-community cohort trial, with a mean of six years follow-up, identified that anaemic patients were more likely to have a MACE event than non-anaemic patients (HR=1.41). 21

Patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), for either known CAD or MI, have been shown to have worse 30-day MACE and one year survival rate if anaemic, with the adverse outcomes directly related to the severity of anaemia. 22

The ESC and American Heart Association (AHA) provide no guidance on iron replacement in CAD due to a paucity of evidence in regard to its benefit. In 1981, Sullivan et al 23 hypothesised that iron was a chronic cardiotoxic, and despite its role in ROS, may promote atherosclerosis and CAD. These claims have since

FIGURE 1: Pathology of iron deficiency in heart failure4 https://ars.els-cdn.com/content/image/1-s2.0-S0735109717420134-fx1_lrg.jpg

been disproven by multiple interval studies. 24 Unfortunately, the time taken to disproving that iron overload was not toxic has resulted in a slow movement towards research into iron deficiency and its role in overall cardiovascular health.

Subsequently, the Ludwigshafen Cardiac cohort trial 25 suggested that those with the lowest levels of iron stores are at highest risk of CAD compared to iron replete sex-matched patients. In contrast to this, a 2015 meta-analyses of 17 studies, with 9,236 patients with CAD, published conflicting evidence. 26 These patients were assigned into three groups for various iron store markers. There were no significant associations between

differing groups for serum ferritin, total iron binding capacity (TIBC), and iron. Higher TSAT did have a lower combined risk ratio of CAD/MI (RR =0.82).

Schrage et al, 27 studied 12,164 individuals from three European population-based cohorts, reviewing associations between AID/FID and incidental CAD, cardiovascular mortality, and all-cause mortality. FID was significantly associated with increased incidence of all three outcome measures, with 64 per cent of the cohort meeting FID criteria. AID however was only statistically significantly associated with incidental CAD, with all-cause mortality being statistically significant in those with severe AID (Ferritin <30). Given FID

includes TSAT, these findings match up to the 2015 meta-analyses, but highlight the difficulties in defining iron deficiency. The hope is for an RCT to investigate the effect of treating iron deficiency in the general cardiology or non-cardiology population.

Iron deficiency and anaemia are common conditions and have significant impacts on cardiology patients. It is often overlooked and undertreated. Current trials, soon to publish their findings, will give us stronger heart failure outcome evidence, which may lead to stronger evidence-based recommendations from the ESC and other organisations.

In the meantime, there is sufficient QoL and functional improvement evidence to support that iron replenishment should be a routine part of standard care, along with the use of left ventricular sparing medications. Iron infusion on a large patient scale is currently restricted, mostly to acute hospital care, requiring our chronic heart failure patients to travel for this potentially outpatient

service. The transition to enable iron infusions in community care settings should be prioritised as we transition the care of chronic conditions to the community, but resources must be put in place to support this. Although the evidence in heart failure is stronger than in other cardiology conditions, there is a suggestion that functional iron deficiency and low TSATs has a significant cardiovascular

morbidity and mortality impact on all cardiology patients. Future research into the role of iron deficiency in the general cardiac population will guide healthcare professionals as to whether there is a benefit in advocating for iron replenishment in these patients. Stronger evidence than that currently available is required before any changes to guidelines can be made. l

Q1. Iron deficiency affects more than two billion people worldwide.

True or false?

Q2. Iron deficiency in cardiology patients can occur without anaemia/reduced haemoglobin.

True or false?

Q3. Serum iron is a reliable indicator of iron stores.

True or false?

Q4. Transferrin saturation (TSAT) measures absolute iron deficiency.

True or false?

Q5. Oral iron supplementation is as effective as parenteral iron supplementation in patients with heart failure.

True or false?

Q6. Iron supplementation improves exercise capacity in both anaemic and nonanaemic heart failure patients.

True or false?

Q7. Iron supplementation has been shown to prospectively improve mortality in HFrEF and HFpEF.

True or false?

Q8. IV iron generally requires multiple treatments over time rather than a single once-off infusion.

True or false?

Q9. Iron is cardiotoxic and promotes atherosclerosis and earlier coronary artery disease.

True or false?

Q10. ESC guidelines state that iron deficiency should be assessed and replaced for all patients with coronary artery disease.

True or false?

Check your answers against the latest module on nursecpd.ie Successful completion of this module will earn you 2 CPD credits

Authors: Dr Robert M Evans, SpR in Cardiology, and Dr Patrick O’Callaghan, Consultant Cardiologist, University Hospital Waterford

1. Rymer JA, Rao SV. Anemia and coronary artery disease: Pathophysiology, prognosis, and treatment. Coron Artery Dis. 2018;29(2):161-7. doi: 10.1097/ MCA.0000000000000598

2. Camaschella C. Iron deficiency. Blood. 2019;133(1):30-9. doi: 10.1182/ blood-2018-05-815944

3. Von Haehling S, Gremmler U, Krumm M, Mibach F, Schön N, Taggeselle J, et al. Prevalence and clinical impact of iron deficiency and anaemia among outpatients with chronic heart failure: The PrEP Registry. Clin Res Cardiol. 2017;106(6):436-43. doi: 10.1007/s00392-016-1073-y

4. Rocha BML, Cunha GJL, Menezes Falcão LF. The burden of iron deficiency in heart failure: Therapeutic approach. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71(7):782-93. doi: 10.1016/j. jacc.2017.12.027

5. McDonagh TA, Metra M, Adamo M, Gardner RS, Baumbach A, Böhm M, et al. ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: Developed by the taskforce for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). With the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur J Heart Fail. 2022;24(1):4-131. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehab368

6. Kvaslerud AB, Hussain AI, Auensen A, Ueland T, Michelsen AE, Pettersen KI, et al. Prevalence and prognostic implication of iron deficiency and anaemia in patients with severe aortic stenosis. Open Heart 2018;5(2):e000901. doi: 10.1136/ openhrt-2018-000901

7. Parsons WB, Jr Cooper T, Scheifley CH. Anemia in bacterial endocarditis. JAMA. 1953;153(1):14-6. doi: 10.1001/ jama.1953.02940180016005

8. Branwood AW. A case of perforated duodenal ulcer and cardiac infarction. Br Heart J. 1947;9(4):263-6. doi: 10.1136/hrt.9.4.263

9. Leshem-Rubinow E, Steinvil A, Zeltser D, Berliner S, Rogowski O, Raz R, et al. Association of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor therapy initiation with a reduction in hemoglobin levels in patients without renal failure. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87(12):118995. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2012.07.020

10. Ratcliffe PJ, O'Rourke JF, Maxwell PH, Pugh CW. Oxygen sensing, hypoxia-inducible factor-1 and the regulation of mammalian gene expression. J Exp Biol. 1998;201(Pt 8):1153-62. doi: 10.1242/jeb.201.8.1153

11. Burgoyne JR, Mongue-Din H, Eaton P, Shah AM. Redox signaling in cardiac physiology and pathology. Circ Res 2012;111(8):1091-106

12. Xu W, Barrientos T, Mao L, Rockman HA, Sauve AA, Andrews NC. Lethal cardiomyopathy in mice lacking transferrin receptor in the heart. Cell Rep. 2015;13(3):533-45. doi: 10.1016/j. freeradbiomed.2018.08.010

13. Groenveld HF, Januzzi JL, Damman K, van Wijngaarden J, Hillege HL, van Veldhuisen DJ, et al. Anemia and mortality in heart failure patients a systematic review and metaanalysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52(10):81827. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.04.061

14. Lewis GD, Malhotra R, Hernandez AF, McNulty SE, Smith A, Felker GM, et al. Effect of oral iron repletion on exercise capacity in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction and iron deficiency: The IRONOUT HF Randomised Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2017;317(19):1958-66. doi: 10.1001/ jama.2017.5427

15. Ducrocq G, Gonzalez-Juanatey JR, Puymirat E, Lemesle G, Cachanado M, Durand-Zaleski I, et al. Effect of a restrictive vs liberal blood transfusion strategy on major cardiovascular events among patients with acute myocardial infarction and anemia: The REALITY Randomised Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2021;325(6):552-60. doi: 10.1001/ jama.2021.0135

16. Swedberg K, Young JB, Anand IS, Cheng S, Desai AS, Diaz R, et al. Treatment of anemia with darbepoetin alfa in systolic heart failure. New Engl J Med. 2013;368(13):1210-9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1214865

17. Anker SD, Comin Colet J, Filippatos G, Willenheimer R, Dickstein K, Drexler H, et al. Ferric carboxymaltose in patients with heart failure and iron deficiency. New Engl J Med. 2009;361(25):2436-48. doi: 10.1056/ NEJMoa0908355

18. Ponikowski P, van Veldhuisen DJ, CominColet J, Ertl G, Komajda M, Mareev V, et al. Beneficial effects of long-term intravenous iron therapy with ferric carboxymaltose in

patients with symptomatic heart failure and iron deficiency†. Eur Heart J. 2015;36(11):65768. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu385

19. Anker SD, Kirwan B-A, van Veldhuisen DJ, Filippatos G, Comin-Colet J, Ruschitzka F, et al. Effects of ferric carboxymaltose on hospitalisations and mortality rates in irondeficient heart failure patients: an individual patient data meta-analysis. Eur J Heart Fail 2018;20(1):125-33. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.823

20. Muzzarelli S, Pfisterer M. Anemia as independent predictor of major events in elderly patients with chronic angina. Am Heart J. 2006;152(5):991-6. doi: 10.1016/j. ahj.2006.06.014

21. Sarnak MJ, Tighiouart H, Manjunath G, MacLeod B, Griffith J, Salem D, et al. Anemia as a risk factor for cardiovascular disease in The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;40(1):2733. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)01938-1

22. Lee PC, Kini AS, Ahsan C, Fisher E, Sharma SK. Anemia is an independent predictor of mortality after percutaneous coronary intervention. J Am Coll Cardiol 2004;44(3):541-6. doi: 10.1016/j. jacc.2004.04.047

23. Sullivan JL. Iron and the sex difference in heart disease risk. Lancet. 1981;1(8233):12934. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(81)92463-6

24. Ma J, Stampfer MJ. Body Iron Stores and Coronary Heart Disease. Clinical Chemistry. 2002;48(4):601-3. doi: 10.1056/ NEJM199404213301604

25. Grammer TB, Kleber ME, Silbernagel G, Pilz S, Scharnagl H, Tomaschitz A, et al. Hemoglobin, iron metabolism and angiographic coronary artery disease (The Ludwigshafen Risk and Cardiovascular Health Study). Atherosclerosis. 2014;236(2):292-300. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2014.07.002

26. Das De S, Krishna S, Jethwa A. Iron status and its association with coronary heart disease: Systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Atherosclerosis. 2015;238(2):296-303. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis

27. Schrage B, Rübsamen N, Ojeda FM, Thorand B, Peters A, Koenig W, et al. Association of iron deficiency with incident cardiovascular diseases and mortality in the general population. ESC Heart Fail 2021;8(6):4584-92. doi: 10.1002/ehf2.13589

AUTHOR: Ruth Morrow, Registered Advanced Nurse Practitioner (Primary Care); Respiratory Nurse Specialist (WhatsApp Messaging Service, Asthma Society of Ireland; and Nurse Educator and Consultant

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a common, preventable and treatable disease that is characterised by persistent respiratory symptoms and airflow limitation that is due to airway and/or alveolar abnormalities usually caused by significant exposure to noxious particles or gases.

The chronic airflow limitation that is characteristic of COPD is caused by a mixture of small airways disease (eg, obstructive bronchiolitis) and parenchymal destruction (emphysema), the relative contributions of which vary from person to person (GOLD, 2022).

In 2019, the National Institute for Health Research in the UK carried out a systematic review, which explored the prevalence of COPD from 19902019 in 65 countries. The study found that the global prevalence of COPD was 10.3 per cent in 30-to-79 year-olds; equivalent to 391.9 million people.

The study also found that the key risk factors for developing COPD include being male, current smoker, having a BMI of less than 18.5, exposure to biomass fuels, and occupational exposure to dust or smoke (Adeloye et al, 2022). Other contributing factors

FIGURE 1: The revised ABCD assessment tool (GOLD)

include genetic factors, lung growth and development, socioeconomic status, asthma and airway hyper-reactivity, chronic bronchitis, and infections.

The paradigm of COPD as a predominantly male disease is changing as smoking rates in both males and females are now similar, and the number of deaths due to COPD among women has surpassed that of men. Women appear more susceptible to the effects of cigarette smoke, developing COPD earlier and with lower cigarette exposure than men. Women also commonly exhibit a COPD phenotype with airway dominant disease in comparison with emphysema and they also vary in response to treatment.

The diagnosis of COPD involves a detailed history, spirometry, investigations, assessment of symptoms.

The patient history should include: Medical and surgical history; Smoking history including pack year history; Occupational history.

Post-bronchodilator FEV1/FVC ratio of 70 per cent or 0.7 indicates COPD. Table 1 illustrates the severity of obstruction using FEV1

Blood screen to include FBC and TFTs; Chest x-ray; ECG.

The measurement of fractional inhaled nitrous oxide (FENO) is a relatively new concept and is now

IN PATIENTS WITH FEV1/FVC <70%

GOLD 1 Mild FEV1 > 80% predicted

GOLD 2 Moderate 50% < FEV1 < 80% predicted

GOLD 3 Severe 30% < FEV1 < 50% predicted

GOLD 4 Very severe FEV1 < 30% predicted

TABLE 1: GOLD (2022) classification based on FEV1

recommended as one of the tools to assess if inhaled corticosteroid therapy (ICS) is indicated for these patients. Approximately 40 per cent of patients with COPD have raised eosinophils. Patients with high eosinophil levels have an increased risk of exacerbations of COPD if they are not on ICS therapy.

The characteristic symptoms of COPD are chronic and progressive dyspnoea, cough, and sputum production that can be variable from day-to-day. Dyspnoea is usually progressive, persistent, and characteristically worse with exercise. Patients may have an intermittent cough, which may be unproductive, but many patients will commonly cough up white/clear non-purulent sputum. Symptoms and their impact on qualityof-life can be assessed using the COPD assessment tool (CAT) test and the Medical Research Council (MRC) dyspnoea scale ( Table 2). The CAT test is a validated eight-item measure of health status impairment in COPD (www.catestonline.org).

0 No breathlessness except with strenuous exercise

1 Shortness of breath when hurrying on the level or walking up a slight hill

2 Walks slower than people of the same a ge on the level because of breathlessness or has to stop for breath when walking at own pace on the level

3 Stops for breath after walking about 100 metres or after a few minutes on the level

4 Too breathless to leave the house or breathless when dressing or undressing

TABLE 2: Medical Research Council dyspnoea scale

The ABCD assessment tool is a useful tool for assessing severity of COPD. The assessment of COPD has been refined to include assessment of symptoms and risk of future exacerbations ( Figure 1).

Pharmacological therapies are used to reduce COPD symptoms, reduce the severity and frequency of exacerbations, and improve exercise tolerance and health status.

Bronchodilator therapy remains the mainstay of the management of stable COPD and has been shown to reduce hyperinflation. The main groups of COPD medications include:

Beta-agonists – these relax smooth

A

SABA OR SAMA

B

LABA or LAMA

SABA: Salbutamol, terbutaline

SAMA: Ipratropium bromide

LABA: Salmeterol, formoterol, indacaterol, olodaterol

LAMA: Tiotropium, umeclidinium, aclidinium, glycopyrronium

MDI with spacer, Easi-breathe, Diskus, Turbohaler

MDI with spacer, Turbohaler, Breezhaler, Respimat

Respimat, Handihaler, Genuair, Elipta, Breezhaler

C

ICS and LABA or LAMA

ICS/LABA: Budesonide/formoterol, vilanterol/fluticasone

ICS/LAMA: Aclidinium/formoterol

LAMA: Tiotropium, umeclidinium, aclidinium, glycopyrronium

Turbohaler, Spiromax, Easyhaler, Elipta

Genuair

Respimat, Handihaler, Genuair, Elipta, Breezhaler

D

LABA with ICS and LAMA

ICS/LABA: Budesonide/formoterol, vilanterol/fluticasone

ICS/LAMA: Aclidinium/formoterol

LAMA: Tiotropium, umeclidinium, aclidinium, glycopyrronium

TABLE 3: Pharmacological treatment options based on COPD classification (GOLD, 2022)

muscle by stimulating the beta2 adrenergic receptors. Beta-agonists can be classified into short-acting (SABA) and long-acting (LABA); eg, salbutamol (SABA), salmeterol (LABA), indacaterol (LABA), vilanterol (LABA), formoterol (LABA), olodaterol (LABA).

Antimuscarinic drugs block the bronchoconstrictor effects of acetylcholine on M3 muscarinic receptors. These can also be classified into short-acting (SAMA) and longacting (LAMA); eg, ipratropium (SAMA), tiotropium (LAMA), umeclidinium (LAMA), aclidinium bromide (LAMA), glycopyrronium (LAMA).

Combining bronchodilators may increase the degree of bronchodilation, whilst lowering the risk of side-effects compared to increasing the dose of a single bronchodilator agent.

Methylxanthines – this group of drugs remain controversial as to their

mechanism of action. There is evidence of bronchodilation in stable COPD. Theophylline is the most commonly used methylxanthine. However, there are significant drug interactions with its use and clearance of the drug declines with age.

ICS should not be used as a single agent in the management of COPD. In patients with moderate to severe COPD, the use of ICS combined with a LABA is more effective than using either agent alone in improving lung function, health status, and reducing exacerbations. Their use in patients with high eosinophil levels have been shown to be beneficial (GOLD, 2022).

To-date, there is no conclusive clinical trial evidence that any existing medications for COPD modify the long-term decline in lung function (GOLD, 2022).

Pharmacological algorithms are

Turbohaler, Spiromax, Easyhaler, Elipta

Genuair

Respimat, Handihaler, Genuair, Elipta, Breezhaler

given for the initiation, escalation, or de-escalation of treatment according to the individual assessment of symptoms and exacerbation risk. In previous publications of GOLD reports, recommendations were only given for treatment initiation. Table 3 illustrates the pharmacological treatment options according to the patient’s COPD classification.

The assessment of inspiratory effort is important to ensure that the patient has sufficient inspiratory flow to optimise deposition of medication to the lungs. Inspiratory effort can be assessed using the In Check Dial metre. Inhaler devices have different inspiratory flow requirements, with dry powder devices requiring a greater effort that soft mist or metre dose inhalers. To improve technique,

≥2 moderate exacerbations or ≥1 leading to hospitalisation

0 or 1 moderate exacerbations (not leading to hospital admission)

Group C

LAMA

Group D

LAMA or LAMA + LABA* or ICS + LABA**

* Consider if highly symptomatic (eg, CAT >20)

** Consider if eos ≥300

Group A A bronchodilator

Group B

A long-acting bronchodilator (LABA or LAMA)

mMRC 0-1 CAT <10

mMRC ≥2 CAT ≥10

FIGURE 2: Initial pharmacological treatment with the ABCD assessment tool (GOLD, 2022)

it is recommended that patients are educated and trained with the appropriate devices. The choice of device should be tailored to the individual, depending on the patient’s ability to use it, their manual dexterity, cognitive function, and taking their preference into account.

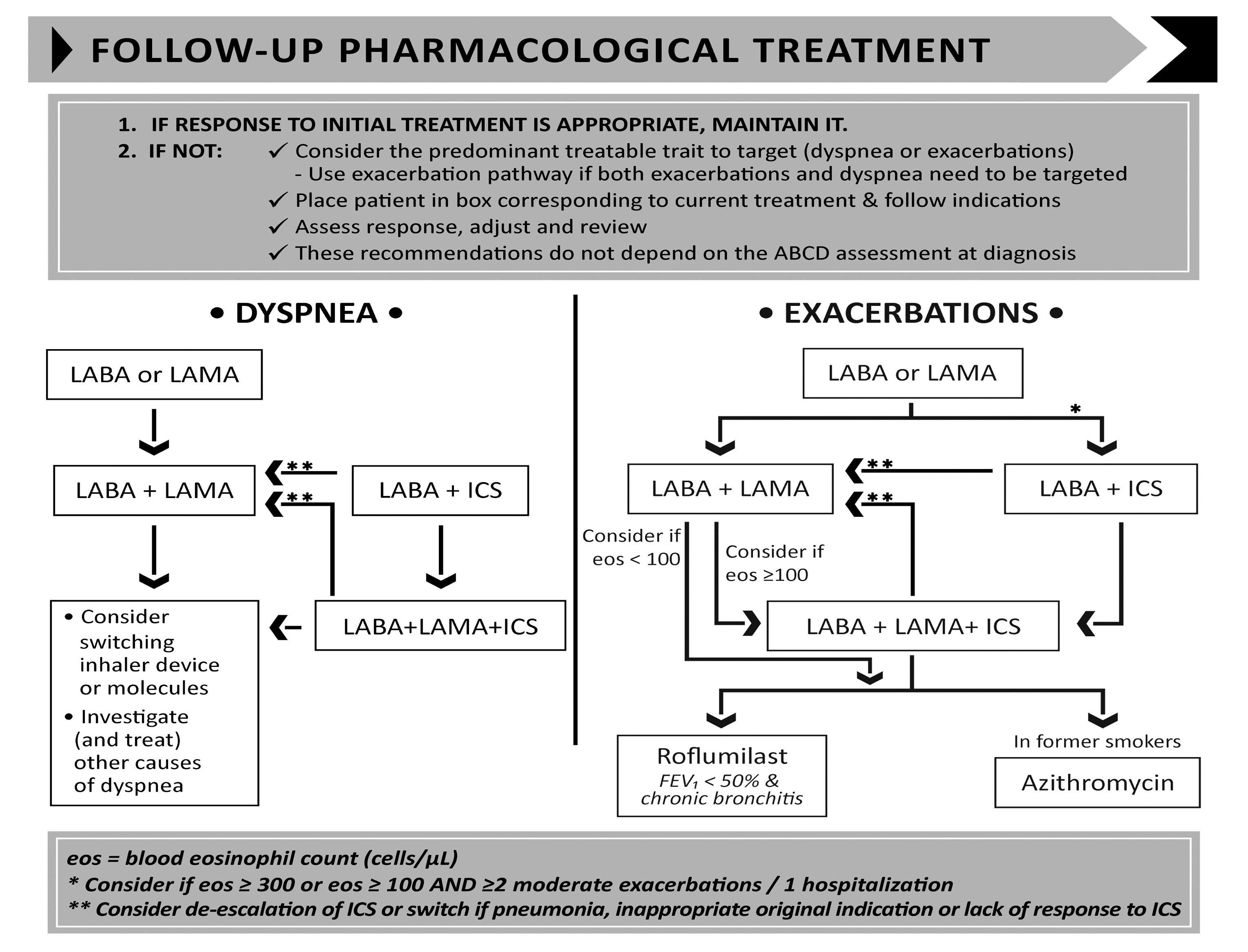

Ongoing monitoring and follow-up GOLD (2022) recommends that regular review of COPD should focus on dyspnoea and exacerbations. Whichever is the most problematic for the patient should be the focus of the review. For patients with persistent breathlessness or exercise limitation on LABA/ICS treatment, LAMA can be added to escalate to triple therapy. Alternatively, switching from LABA/ICS to LABA/LAMA should be considered if the original indication for ICS was inappropriate (eg, an ICS was used to treat symptoms in the absence of a history of exacerbations), or there has been a lack of response to ICS treatment, or if ICS side-effects

AT ALL STAGES, DYSPNOEA DUE TO OTHER CAUSES (NOT COPD) SHOULD BE INVESTIGATED AND TREATED APPROPRIATELY

warrant discontinuation (GOLD, 2021). At all stages, dyspnoea due to other causes (not COPD) should be investigated and treated appropriately. Inhaler technique and adherence should be considered as causes of inadequate treatment response. Where exacerbations are the predominant trait, prophylactic macrolide antibiotics should be considered following cardiovascular assessment. Assessment of eosinophils can be useful when the patient is experiencing exacerbations. If the

eosinophils are above 0.3 or if the patient has experienced two or more exacerbations with one hospitalisation, initiating or escalating ICS can be beneficial (GOLD, 2021). Roflumilast, another treatment option, is a selective inhibitor of phosphodiesterase-4 (PDE-4) that has unique antiinflammatory activity and is used to treat and prevent exacerbations.

Smoking cessation is of paramount importance in the management of COPD regardless of disease severity. Support given by health professionals significantly increases quit rates over self-initiated strategies. Even a brief (three-minute) period of counselling to urge a smoker to quit results in smoking quit rates of 5-to-10 per cent. Smoking cessation should be encouraged at all severities of the condition. Nicotine replacement therapy (nicotine gum, nasal spray, transdermal patch, sublingual tablet, or lozenge) as well as treatment with varenicline reliably increases longterm smoking abstinence rates and are significantly more effective than placebo (GOLD, 2022).

Pulmonary rehabilitation has been proven to show significant benefits in reducing dyspnoea, fatigue and exacerbations, and improving qualityof-life in people with COPD. Although an effective pulmonary rehabilitation programme is six weeks, the longer the programme continues, the more effective the results. If exercise training is maintained at home, the patient’s health status remains above prerehabilitation levels (McCarthy et al, 2015).

Patients should be encouraged to be as physically active as possible. The aim is to achieve 30 minutes of aerobic

FIGURE 3: Follow-up treatment (GOLD, 2022)

activity daily, eg, walking, cycling, and swimming. Exercises such as chest and shoulder exercises, shoulder raises, step ups, and sit-to-stand exercises should be encouraged as this will assist in maintaining upper body strength with the ultimate aim of prevention of muscle wasting.

Breathing exercises, such as pursedlip breathing and the active cycle of breathing, can help manage dyspnoea

and assist in expectorating sputum. These techniques are available on www.copd.ie .

Energy conservation is based on the 4Ps:

Make a list of what you have to do;

Place the task in order of importance, into what you need to do, want to do, and should do; Get rid of any unnecessary tasks; Decide if someone else can do some tasks for you; Change between light and heavy tasks.

Work at a slow steady pace;