6 minute read

A Night Owl Emerges from the Dark – Part 2 - Paul Perton

Paul Perton, Marketer, Writer, Photographer

Beginning the move to Devon

Advertisement

The empty space where the 4709 frames had been at Llangollen

On the road at last – Leaving Llangollen for Devon The Peaky Finders team! (l-r) Leaky Finders’ George Balsdon, Paul Carpenter, 4709’s Richard Croucher and Leaky Finders’ Rory Edwards,

its long, slow journey south. Out in the open, suspended from the crane, there was just a hint of the finished size of this giant 2–8–0. It will weigh around 83 tonnes when complete, with the tender accounting for another 46 tonnes.

Now firmly in the care of Leaky Finders’ Rory Edwards and George Balsdon at Hele near Exeter, work on 4709 began to ramp up quickly to make up for time lost to the COVID lockdown. Waiting at Leaky Finders was a long list of jobs that Rory and George could check, measure, do and get underway. First up on the list was a thorough check of everything about 4709’s chassis, including the overall dimensions, correct alignment of the running board brackets, measuring all the holes and the accuracy of the horn ties. This was done to confirm that all holes had been drilled as per the GWR drawing and any discrepancies noted for rectification. The horn ties were corrected at Llangollen but were finally checked again. The running boards were then mounted, with

After weeks of COVID-caused delays, the chassis of 4709 inched its way out of the Llangollen workshops and into the daylight for the first time early in August, en-route to a new home in Devon. Limited headroom meant that the 10+ tonne chassis had to be moved out of the shed, to be craned on to the low loader for

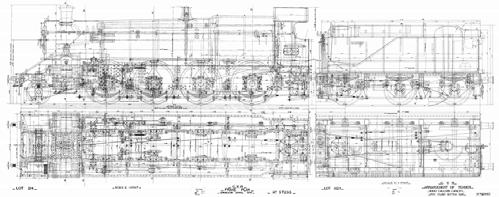

The CAD drawing for the new running boards

an allowance being made where necessary to accommodate the fitting of the cylinders, once delivered from the foundry.

Joining 4709 from Tyseley were the pony wheelset, axle boxes and pony truck, which will require a stretcher to be fabricated. So, yet more preparations were necessary, and a quotation provided before work could begin. Hard on the heels of the pony stretcher was the vacuum pump bracket, which, similarly had to be estimated and approved before construction can begin.

Moving on from new manufacture, the Leaky Finders team could then move on to the overhaul of the motion parts currently in our store and the refurbishment of the other donor parts, so vital to this (re)build.

Meanwhile, the GWS is compiling a set of all existing 47xx drawings, which were copied and issued to all engineering members of the 4709 team. The GWS is also considering how best to develop an efficient system such that key players will have electronic copies of all essential documentation for main line running.

Three Donor Locomotives (l-r), 4115, 5227 and 2861, in the snow at Barry Various components awaiting installation

A very sad and forlorn donor engine 5227 at Didcot

Donor parts and re-metalling

Donors. Every preservation project needs them, but the donors it’s all too easy to overlook are those that had no say in their giving; mostly the Barry Ten, the last of the steam locos that have been outside in the Woodham Brothers’ scrapyard, unmoving and largely unloved since the early–mid sixties.

Donor parts

• With a completely wrecked LH cylinder casting, 5227 now stands at GWS Didcot, having volunteered eight axle boxes, horns, and various other components. • 4115 has given us its six driving and coupled wheels, extension frames, pony truck and some motion parts. • 2861 has given us its complete cylinder block, which has been used in 4709’s frames as a template but is to be replaced once The Night

Owl’s own cylinders are available. The loco’s boiler has also served time with the 4709 project but is unlikely to be a permanent solution as other options are considered and costed.

The driving wheelsets for 4709 wait at Tyseley, having had their tyres re-profiled and where the crankpin collars and lead balance weights will be fitted. 5227’s axleboxes and horn guides have been fitted on to 4709’s frames at Llangollen.

Driving wheelsets at Tyseley

(Above left) 4709’s axle boxes

(above) 4709’s tender to be (after rebuild)

(left) 5227’s destroyed cylinder casting (above right) 4709’s pony truck at Tyseley, kindly donated by 4115

Cylinder work – A Major Technological Breakthrough for Restoration

Held up. Delayed. Postponed. Rescheduled. Suspended. Whatever your word for it is, the casting of 4709’s cylinders has been a source of frustration for Chief Engineer Paul Carpenter and his team. The work was due to start more than nine months ago, but a slight engineering delay let Bradley Manor’s cylinders nip in front of ours in the queue and suddenly COVID–19 arrived, and everything stopped. The foundry used by previous projects then went into receivership so the project have had to find another foundry willing to undertake this complex work and progress round a steep learning curve.

Not only is that a hassle because we’re building a giant freight 2–8–0, but so much depends on the final castings, including the critical measurements and dimensioning of the cylinders, horn guides and eventually, 4709’s motion. In our case, there’s another

2861 cylinders installed in 4709’s frames, as a template for measurement, while still at Llangollen

consideration; the casting process will be the first for the GWS that uses sacrificial polystyrene patterns to create the sand moulds, rather than the historical wooden types, which were used for the cylinders on the Saint and Steam Rail Motor.

Polystrene patterns demand a new set of knowledge, skills and persistence !

Paul Carpenter explains; “Traditionally, patterns for metal casting have always been made from wood and represent the history of a complete industry. Patternmaking requires skill, knowledge and demands massive experience on the part of the patternmaker, invariably built atop a rigidly controlled apprenticeship.”

In more recent times, and with the everwidening application of CAD–based design, several locomotive groups have experimented with the use of sacrificial polystyrene patterns. This offers superb accuracy, a radical speeding–up of the pattern making process as well as a significant cost saving. Once the design and 3D-modelling of the component is complete

(below) The pattern ready to go to the foundry

(Right) above) the casting before machining and (below) after machining

and approved, the CAD data is downloaded to a 3D routing machine, which sculpts the pattern from a solid block of polystyrene.

Casting the Cylinders

In the case of 4709’s cylinders, the complexity of the completed casting is such that it is impossible to produce the pattern as a single component. The solution has been to produce the final pattern as a number of sections, which then have been glued together to produce a perfect replica of the required cylinder block, together with all the vital casting and machining tolerances in place.

From an engineering perspective, the technique has several clear advantages: • All the internal ports and passages can be cast as an integral part of the finished job • Core boxes are no longer required

Once assembled and complete, the polystyrene pattern is utilised in a similar fashion to the traditional wooden pattern and encased in casting sand, ready for casting. The essential difference is that where the wooden pattern would have been removed from the rammed sand prior to pouring metal, the polystyrene pattern is left in place. The molten cast iron is then poured into the mould in