37 minute read

March

INTERNATIONAL

DAYS MARCH

Advertisement

1st March – Zero Discrimination Day Zero Discrimination Day is to promote equality before the law and in practice. First celebrated in 2014, the ask is to speak up and prevent discrimination from standing in the way of achieving ambitions, goals and dreams. Though a focus for this Day continues towards countering discrimination of those with HIV/AIDS and the LGBTQI community, this Day also symbolises the need to fight against any form of discrimination. In Australia, the Australian Human Rights Commission has statutory responsibilities under the Age Discrimination Act 2004, Australian Human Rights Commission Act 1986, Disability Discrimination Act 1992, Racial Discrimination Act 1975 and the Sex Discrimination Act 1984. With Members across the world, and graduate students and academics residing here at Graduate House, we give best endeavour against any form of ‘ism.

3rd March – World Wildlife Day World Wildlife Day is to support animals and plants and to raise awareness of our globe’s diversity of wildlife and marine life. With increasing numbers of endangered and extinct species, we must act to conserve our planet. The 2021 theme is Forests and livelihoods: sustaining people and planet. Jackson Wild, The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) and the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) are organising an international film showcase of our planet’s valuable forests, their extensive ecosystems services, and the livelihoods that the forests help to sustain. The winners and final round films from this international competition, will be shown throughout 2021. As noted by Lisa Samford, Executive Director of Jackson Wild: “Covering over a third of the Earth’s surface, forests are a home to 80% of all terrestrial animals, plants and insects and sustain the livelihoods of millions of people, providing ecosystems services and resources that are essential to the global economy. Rich biodiversity is essential to the health of our planet. With the impact of climate change escalating every day as growing numbers of species edge toward extinction we must act quickly and decisively for our own survival.”

8th March – International Women’s Day International Women’s Day is a global day celebrating the social, economic, cultural and political achievements of women. The day also marks a call to action for accelerating gender parity. Significant activity is witnessed worldwide as groups come together to celebrate women’s achievements or rally for women’s equality. Marked annually on 8th March, International Women’s Day (IWD) is one of the most important days of the year to celebrate women’s achievements, raise awareness about women’s equality, lobby for accelerated gender parity and fundraise for female-focused charities.

15th to 21st March – Harmony Week Harmony is a noun for agreement in such domains as feeling, sound, look, feel or smell. Synonyms include accord, concord, cooperation, like-mindedness and unanimity. Harmony Week celebrates Australia’s cultural diversity, inclusiveness, respect and a sense of belonging for everyone.

17th March – St Patrick’s Day A cultural and religious celebration of the Irish, Saint Patrick’s Day marks the traditional death date of Saint Patrick (c.385 – c.461), a patron saint of Ireland; and commemorates the arrival of Christianity in Ireland. Celebrations include public parades and festivals, social visits (céilís) and the wearing of green attire or shamrocks. It is widely celebrated across the world, especially amongst the Irish diaspora.

20th March – French Language Day French Language Day explores the influences of French, a language that developed from Latin between the 5th and 8th centuries and that is now spoken in over 25 countries. A primary romance language with many dialects, French, with English, is spoken on all five continents by around 275 million speakers. French is one of the six official languages of the United Nations. Established in 2010, the Day marks the 40th anniversary of the International Organization of La Francophonie.

20th March – World Frog Day World Frog Day is an annual observance of the tailless amphibian. Created in 2009, the intent is to stem the extinction of many threatened species of frogs. In the past decade, approximately 170 species of frogs have vanished due to human activity and fungal infections. As frogs are particularly sensitive to their surroundings, the presence of frogs in an ecosystem is an indicator of a healthy, biodiverse ecosystem and environment. If their habitat were to become degraded or polluted, they are among the first to feel the impact. In Australia alone, there are an estimated 230 species of frogs, with at least 37 species listed as critically endangered, endangered or vulnerable on the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation list. Activities to assist

20th March – International Day of Happiness All 193 United Nations member states have agreed for happiness to be given greater priority. In 2011, the UN General Assembly adopted a resolution which recognised happiness as a “fundamental human goal” and called for “a more inclusive, equitable and balanced approach to economic growth that promotes the happiness and well-being of all peoples”. In 2012 the first ever UN conference on Happiness took place and the UN General Assembly adopted a resolution which decreed that the International Day of Happiness would be observed every year on 20th March. It was celebrated for the first time in 2013.

21st March – World Down Syndrome Day Down syndrome (trisomy 21) is a genetic condition that occurs at conception. While most people have 23 pairs of chromosomes in each of their cells (46 in total), those with Down syndrome have an extra chromosome 21. Like every other human being, people with Down syndrome differ from individual to individual, and have areas of strength and areas where they need more support. World Down Syndrome Day has been observed by the United Nations since 2012 and provides an annual opportunity for the global Down syndrome community to connect, share ideas, experiences and knowledge, empower each other to advocate for equal rights for people with Down syndrome, and reach out to key stakeholders to bring about positive change. 21st March – International Day of

Nowruz There are many different ways to spell and pronounce the word that means ‘new day’: Nowruz, Novruz, Navruz, Nooruz, Nevruz and Nauryz. Celebrated on the day of the astronomical vernal equinox and the first day of spring in the northern hemisphere, International Day of Nowruz is also seen as the beginning of the new year by more than 300 million people globally. It has been celebrated for over 3,000 years in the Balkans, the Black Sea Basin, the Caucasus, Central Asia, the Middle East and other regions, and was inscribed in 2009 on the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity. Nowruz is to promote peace and solidarity between generations and within families, as well as reconciliation and neighbourliness, thus contributing to cultural diversity and friendship among peoples and different communities. Celebrating Nowruz means the affirmation of life in harmony with nature, awareness of the inseparable link between constructive labour and natural cycles of renewal and a solicitous and respectful attitude towards natural sources of life.

21st March – World Poetry Day Poetry, is defined as a literary work in which the expression of feelings and ideas is given intensity by the use of distinctive style and rhythm, as poems collectively or as a genre of literature. It is also used to describe a quality or experience reflecting the beauty, intensity of emotions and harmony regarded as characteristic of poems. Established in 1999, World Poetry Day is to support linguistic diversity through poetic expression and to increase the opportunity for endangered languages to be heard. It is an occasion to honour poets, revive oral traditions of poetry recitals, promote the reading, writing and teaching of poetry, foster the convergence between poetry and other arts such as theatre, dance, music and painting, and raise the visibility of poetry in the media. As poetry continues to bring people together across continents, all are invited to join in. Practised in every culture and on every continent, poetry speaks to our common humanity and our shared values, transforming the simplest of poems into a powerful catalyst for dialogue and peace.

22nd March – World Water Day The hashtag #water2me reflects conversations about what water means to people around the world. Water is undoubtedly central and important to us all, however it means different things to different people. On World Water Day, question how water is important in your home and family life, and for your livelihood, cultural practices, wellbeing and local environment. In households, schools and workplaces, water means health, hygiene, dignity and productivity. In cultural, religious and spiritual places, water has a connection with creation, community and oneself. In natural spaces, water brings life, peace, harmony and preservation. Stating the obvious, water is under extreme threat from growing populations, increasing agricultural and industry demands, and climate change. On this Day, we acknowledge how to value water properly and to safeguard it effectively for everyone.

22nd March – World Meteorological Day World Meteorological Day marks the establishment in 1950 of the Convention establishing the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) (though it had been around since 1873). The 2021 theme isThe Ocean, our climate and weather. The Ocean covers 70% of the Earth’s surface, provides vital resources, is the major driver of the world’s weather and climate and stores more than 90% of excess heat generated by human activities.

24th March – International Day for the Right to the Truth Concerning Gross Human Rights Violations and for the Dignity of Victims The International Day for the Right to the Truth Concerning Gross Human Rights Violations and for the Dignity of Victims pays tribute to the memory of Monsignor Óscar Arnulfo Romero who was murdered in 1980. It is to acknowledge also the right to the truth in the context of gross violations of human rights and grave breaches of humanitarian law. The purpose of the Day is to: • honour the memory of victims of gross and systematic human rights violations;

• promote the importance of the right to truth and justice for the relatives of victims of summary executions, enforced disappearance, missing persons, abducted children and torture;

• pay tribute to those who have devoted their lives to, and lost their lives in, the struggle to promote and protect human rights for all; and • recognise Archbishop Óscar Arnulfo Romero of El Salvador who was assassinated on 24th

March 1980, after denouncing violations of the human rights of the most vulnerable populations and defending the principles of protecting lives, promoting human dignity and opposition to all forms of violence.

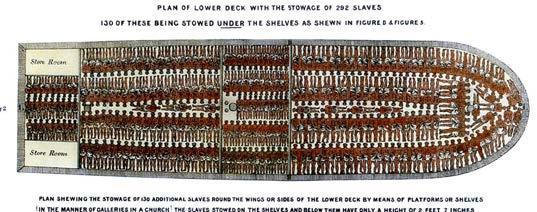

24th March – World Tuberculosis Day World Tuberculosis Day marks the day in 1882 when Dr Robert Koch announced his discovery of the bacterium that causes tuberculosis (TB) and thus opened the way towards diagnosing and curing this disease. The Day is to raise public awareness about the devastating health, social and economic consequences of tuberculosis, and to end the global tuberculosis epidemic. Tuberculosis mainly affects the lungs. The bacteria that cause tuberculosis are spread from one person to another through tiny droplets released into the air via coughs and sneezes. Many strains of tuberculosis resist the drugs most used to treat the disease. People with active tuberculosis must take several types of medications for many months to eradicate the infection and prevent development of antibiotic resistance. 25th March – International Day of Remembrance of the Victims of Slavery and the Transatlantic Slave Trade First observed in 2008, International Day of Remembrance of the Victims of Slavery and the Transatlantic Slave Trade remembers those who suffered and died through the transatlantic slave trade, the worst violation of human rights in history. For over 400 years, more than 15 million African men, women and children in the 16th to 19th centuries were the victims of enslavement and transportation across the Atlantic Ocean to the Americas. The Day also serves to raise awareness on the dangers of unfettered racism and prejudice, and of systems that support discrimination, inequality and supremacism.

25th March – International Day of Solidarity with Detained and Missing Staff Members Since the founding of the United Nations (UN) in 1945, hundreds have lost their lives in its service. With an increasing scale and number of UN peacekeeping missions, more lives were lost during the 1990s than in the previous four decades combined. Recognising the increased likelihood of further UN-service related deaths, the Convention on the Safety of United Nations and Associated Personnel was adopted by the United Nations General Assembly on 9th December 1994. The International Day of Solidarity with Detained and Missing Staff Members marks the abduction in 1985 of Alec Collett, a former journalist who was working for the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA). His body was found 24 years later in Lebanon’s Bekaa Valley in 2009. This Day is to mobilise action, demand justice and strengthen

the resolve to protect UN staff and peacekeepers, as well as colleagues in the non-governmental community and the press.

27th March, 2021 at 8:30pm to 9:30pm – Earth Hour Started by World Wildlife Fund (WWF) and partners as a symbolic lights-out event in Sydney in 2007, Earth Hour is now one of the world’s largest grassroots movements for the environment. Held every year on the last Saturday of March, Earth Hour engages millions of people in more than 180 countries and territories, switching off their lights to show support for our planet. Beyond this symbolic action of switching off, Earth Hour has become a catalyst for positive environmental impact, driving major legislative changes by harnessing the power of the people and collective action.

During Earth Hour try: 1. switching off your lights at 8:30PM for one hour; 2. dining-in-the-dark; 3. tuning in to live Earth Hour streams; 4. board gaming or book reading by candlelight; 5. watching movies with an Earth Hour theme; 6. signing the Voice for the Planet petition; 7. camping in your backyard or living room; 8. tweeting your winning poster @

OneMinuteBriefs and @earthhour with hashtag #EarthHour!; 9. hearing from Sir David Attenborough and

Greta Thunberg; 10.playing the Heads up! card game; 11.taking night photographs or “light-painting”; 12.learning more about the how-to of sustainability; 13.creating a mini-golf course using household objects; 14.creating your own Rube Goldberg machine; 15.painting by candlelight; 16. writing a letter to your future eco-warrior self; 17.hosting an eco-friendly fashion show; 18.dancing silently; 19.jamming with acoustic instruments; 20.trying Yoga; 21.shadow puppeteering; and/or 22.indoor scavenger hunting.

28th to 29th March – Holika Dahan and Holi For many traditions in Hinduism, Holi is a celebration of the killing of Holika to save Prahlada, a devotee of God Vishnu. In the days leading up to the festival, bonfires are prepared with an effigy of Holika, who tricked Prahlada into the fire, placed on the top of the pyre. Coloured pigments, food, drinks and festive seasonal foods such as gujiya, mathri, malpuas and other regional delicacies are also prepared. On the eve of Holi, typically at or after sunset, the pyre is lit, signifying Holika Dahan. The ritual symbolises the victory of good over evil. Holi — also known as the festival of spring, the festival of colours or the festival of love — is celebrated the next day to mark the arrival of spring, the end of winter and the blossoming of love.

Australia’s COVID-19

quarantining – an abrogation of federal responsibilities! There is no national plan.

by Rhonda Boyle

Perhaps the most contentious issue of our COVID year is who is in charge of quarantining? With continuing outbreaks of COVID-19 linked to incoming travellers, Australians have reacted with astonishment that quarantining issues were not foreseen and planned for years ago. How did we end up where we are and what should be done about it? * * *

It seems the handballing of quarantine to the states and territories by the federal government has some legitimacy about it. On that, we note that the eight jurisdictions agreed, with little complaint and with no legal challenge. At the federal level, there has been no coordination of a national approach and there is no sign of long-term planning. Overriding everything, however, is that the federal government is responsible for quarantine under the Constitution and while it may have effectively delegated those responsibilities to the states and territories, it should be held to account for all outcomes, including the costs of continuing lockdowns.

The meaning of quarantine for Australia in the COVID age

Let’s define quarantine as a state, period, or place of isolation in which people, animals or plants are placed due to concerns about exposure to transmittable diseases or invasive pests. With COVID-19 we do not need to deal with animals or plants. However, that hardly helps simplify the discussion of the quarantine of humans in Australia.

John Hewson in the Sydney Morning Herald (14th January 2021) wrote: “Quarantine is a clear national responsibility explicitly designated as such by S51 of the Constitution.” Peter Van Onselen in The Australian (25th July 2020) wrote: “Simply put, the Australian Border Force is in charge of incoming arrivals, with the commonwealth given constitutionally articulated responsibility for quarantining. The Constitution, in section 51 (IX), lays out in black and white that the commonwealth, not the states, has oversight for quarantine. It is the basis for the Quarantine Act, which has not been legally challenged since 1908, including during the 1919 pandemic. We also now have the Biosecurity Act (2015), which provides extremely broad powers, and it mandates

Historical perspective on quarantine

Useful and extensive historical summaries are available from the ABS Year Book archives and from the Victorian Parliament. Both examine quarantining in Australia from the arrival of the First Fleet in Sydney. Settlers, convicts and soldiers were carriers of infectious diseases common at the time, including smallpox, cholera and typhoid. It is estimated that smallpox wiped out about 50% of the indigenous population. Over time, the various colonies would handle quarantine independently. Quarantine centres such as at North Head and Point Nepean were established. By the time of Federation in 1901 it was well accepted that quarantine should be a federal responsibility. Thus, the Australian Constitution lists quarantine in the commonwealth’s legislative powers. Quarantine powers were conferred from the states to the commonwealth through the Quarantine Act (1908) and establishment of the Federal Quarantine Service in 1909.

However, conflicts between the commonwealth and the states about responsibilities for quarantine and health soon developed. Australia’s control of the Spanish flu epidemic (1918-19) involved a form of mass quarantining, with large numbers of returning troops being sent into isolation. Arrangements broke down, with each state following its own course of action, resulting in inconsistent policies on border closures. Spanish flu ultimately infected about 40% of the population, killed about 15,000 and possibly 50% of some Indigenous communities. At the end of the crisis, the commonwealth established a new department of health that was intended to be the focal point for pandemics and quarantine measures. However, over the next 100 years complacency led to lack of national planning. Quarantine stations around the country were gradually decommissioned, and some specialty centres, such as Melbourne’s Fairfield Infectious Diseases Hospital, were closed or roles redefined. In the 1980s, the federal responsibilities for animal and plant quarantine were removed from the health department to the department responsible for agriculture and primary industry. In the 20th century, after the Spanish flu, the major worldwide epidemics affecting Australia included polio, Asian flu and HIV/Aids. In the early 21st century – that is, the past 20 years – the threats of SARS-CoV-1, MERS, Ebola, Zika and Swine flu (H1N1) were negligible or contained within Australia. With Swine flu, which did reach our shores, it seems nationwide cooperation for containing outbreaks worked effectively. Despite unclear government responsibilities, Australia has a history of dealing with epidemics and pandemics with general success. However, the loose arrangements between the commonwealth and state governments over quarantine in regard to health would be sorely tested with COVID-19 when the country would require mass quarantine for the first time since the Spanish flu.

How prepared were we for another health crisis?

The Victorian Parliament document says: “History also reminds us that pandemic outbreaks are often forgotten, despite the impacts they inflict on societies.” We have been warned by experts that pandemics will increase in frequency and severity due to the growing global population and international travel, incursion of human settlements into wildlife habitat, live animal trade and modern livestock management practices. A 2004 CSIRO report writes: “Infectious diseases previously unknown in humans have been increasing steadily over the last three decades. More than 70 per cent of these emerging diseases are zoonotic in nature – passing from animals to people, for example influenzas from poultry or pigs…”

A 2004 report by the Chief Medical Officer also notes the potential for exotic viruses to spread around the world: “SARS reminds us that new diseases will continue to arise as infectious agents mutate and adapt to exploit new ecological opportunities. We cannot assume, as was widely trumpeted in the 1960s and 1970s, that we have conquered communicable diseases. No-one can predict the next emergency, although we can all be wise after the event.” Since 2000, the world’s population has grown from 6.1 billion to 7.8 billion. Between 2000 and 2018 the number of international travellers per year doubled, while for the Asia-Pacific region it tripled. The number of international visitors to Australia was 4.9 million in 2000, reaching 8.6 million in 2019; the number of visitors from China went from 120,000 to more than 1.3 million.

Despite all these pointers to the likelihood of new pandemics and their potentially devastating consequences, Australia would be poorly prepared for COVID-19.

The Coate Inquiry noted that recommendations from a review after the H1N1 pandemic in 2009 to clarify the roles and responsibilities of all governments for the management of people in quarantine, both at home and in other accommodation, during a pandemic was not undertaken.

Important legislation, though, was passed in 2015 when the commonwealth Biosecurity Act 2015 replaced the Quarantine Act of 1908. This summary in Wikipedia explains how it is jointly governed and administered by two federal departments, the Department of Health and the Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment. The powers are explained in this article in The Conversation. Prior to 2015 many of those powers weren’t available. The Attorney General on 3rd March 2020 stated that “the biosecurity laws allow the government to do a range of things based on the best medical advice from the Chief Medical Officer … there are a range of powers that are available that were designed specifically to handle something as serious as a pandemic. … many of the orders require very close cooperation between the Chief Medical Officer of the commonwealth and medical officers in the states … it’s very much a cooperative set of circumstances. And the states have their own variations of these laws.” Further, despite this powerful legislation, a major flaw seems to be that none of the existing commonwealth or state pandemic plans dealt with mandatory, mass quarantine. The Coate Inquiry again: “… it would be unfair to judge Victoria’s lack of planning for a mandatory quarantining program given the commonwealth, itself, had neither recommended nor developed such a plan.”

A Federal Government with no national quarantine plan

By mid-March 2020, international arrival numbers were slowing down, but still more than 25,000 a day. By late-March, Australia was approaching 4,000 infections, overwhelmingly overseas acquired or sourced, with typically two to four new infections arriving each plane load. It became an increasing problem that some returned travellers who had tested positive were not self-isolating as directed. Something needed to be done to stem the growth of community transmission.

The National Cabinet met on 27th March 2020.

The Prime Minister arrived with full control of international arrivals and federal detention centres, his own extensive experience in border control and biosecurity legislation with extremely broad commonwealth powers that superseded those of the states.

However, as reported by Paul Bongiorno, the states were shocked when the national leader arrived at the meeting with no quarantine plan. It seems the state and territory leaders had no choice but to devise their own plans. The meeting would result in two major decisions, apparently resulting from a proposal by the premiers of NSW and Victoria, the two most populous and vulnerable states:

• As of 28th March 2020 all incoming travellers would be required to undertake a 14-day supervised hotel quarantine period. • The eight states and territories were required to run the hotel quarantine system. The system was to be operational in 36 hours. At the time of the meeting there were about 7,000 arrivals per day, though trending downwards. It is estimated that the number in quarantine after the first 14 days would peak at about 20,000.

The Coate Inquiry noted that lack of planning and such short notice was a most unsatisfactory situation from which to develop such a complex and high-risk program. All (or most) arriving passengers have been quarantined since that time. From the National Review of Hotel Quarantine it seems that by 28th August 2020, some 130,000 people had undertaken hotel quarantine with approximately 96,000 international cases and 34,000 (or 26%) domestic cases. Those numbers would be much larger by now. The Commonwealth would control the number of arrivals but would not, it seems, offer access to or establish remote centres for quarantining. Hewson wrote: “A clear acceptance of its responsibility would have seen the Morrison government establish quarantine centres around Australia for all incoming arrivals.” Despite using Christmas Island early in the pandemic, no similar federal offer seems to have been made. Except for Howard Springs in the NT, the states and territories have been stuck with CBD-based systems that they might have to operate for some years to come. In relation to securing our borders and quarantine, Onselen wrote in July that these “are the responsibilities of the national government, not the states”, that failure occurred “… once power was abdicated to them”, that the “fingerprints of failure by the commonwealth are nowhere to be seen, leaving state governments to wear the odium for mistakes made”.

What needs to be done in the short and long term

Can our ‘cobbled-together’ system of hotel quarantine prevent a serious third wave somewhere in Australia during 2021? Can Australia survive another pandemic without a national coordinated plan? We should not assume vaccines are the total solution. There are too many unanswered questions about the current COVID-19 vaccines: How effective, and how long for, can the vaccinated still become infectious and spread the virus? Will an annual shot be required? Will vaccinated travellers still have to quarantine? We have seen that the science, and the virus itself, is constantly evolving and we cannot assume Australia will be able to ‘go back to normal’ by mid-2021. While new highly transmissible variants of the virus are appearing, will more alarming variants appear? Health Department boss and former federal Chief Medical Officer Brendan Murphy predicts Australia will spend most of this year with overseas border restrictions still in place despite a vaccine rollout, and that even if a lot of the population is vaccinated, it is not known whether that will prevent transmission of the virus. He expects quarantine will continue for some time.

Quarantine sites should be remote from population centres

The CBD-based system has proven to leak unpredictably, with immense consequences, and should be phased out. The risks of hotel quarantining outbreaks might be independent of city size, but the cost of lockdowns and contact tracing is greatly accentuated in Melbourne and Sydney due to their bigger areas and populations and higher densities, with greater flow-on costs to their economies and the entire country. Sydney has been accepting about 50% of all arrivals which magnifies risk even more. The many options include upgrading federal detention centres, mining camps and tourist

resorts. These quarantine centres would employ well-paid FIFO/DIDO staff on site. Outside pandemics, these specialised facilities can be used for other purposes. The costs of setting up remote centres need to be balanced against the extraordinary ongoing disruption and impacts caused by local lockdowns and border closures, including the costs of testing tens of thousands each time there is an outbreak and having to extend support such as JobSeeker.

After 100 years we need a national quarantine plan

The warnings are that there will be more frequent and possibly more dangerous pandemics. We need to overhaul federal and state planning and coordination for pandemics, in particular mass quarantining. Had proper planning been in place some years ago we would have experienced a much more cost-effective, humane and cohesive approach. Given the warning of future diseases and the rapidity with which the world is changing due to human activity, we need to act as if another pandemic is just around the corner. We should begin this process and start to implement it even as we continue to manage and mop up from the current pandemic and begin a vaccination program. This is a task for the commonwealth and will place us in a far better position next time. We need to learn from our mistakes, anticipate the worst, and work together as a nation. * * *

This is an edited version of an article that originally appeared in Pearls and Irritations. See the full article: https://bit.ly/2MGqpF8. Rhonda Boyle has a background in science, urban planning, environment policy and climate change, and worked for the Victorian Government in a variety of roles. She now coordinates a global movement known as PASK (Pianists for Alternatively Sized Keyboards) to increase the availability of piano keyboards with narrower keys given the conventional keyboard is too large for the majority of pianists.

Daisy Feller

Ms Daisy Feller is a former Resident Member who currently lives in Atlanta, Georgia, USA. She was the recipient of a Graduate House Bursary to support coursework studies, presented at the Annual General Meeting in 2018. We caught up with Daisy recently via an email interview.

Daisy Feller

Unexpected Deviations

Vital Stats: Qualifications/Accreditations

MA Creative Writing, Publishing and Editing from the University of Melbourne, BA Russian Language and Literature from Portland State University.

What has been your pathway since graduating? What was your first job after graduation and how did that job prepare you for your later positions? Any lessons learnt?

My first job was as an editor, which is the field in which I did my masters. I learned quickly that editing wasn’t right for me, and shifted roles to become an analyst. This taught me the very important lesson that it’s easy to change your career path and continue exploring even after you’ve completed your education. This exploration led me to my current job as a writer at Microsoft.

Did you have any residencies, internships or anything else that ultimately led you to where you are today?

Living at Graduate House completely changed the course of my career. Getting to know students outside of the arts in sectors like business, IT and engineering allowed me to explore these fields, eventually leading me to working in both business and tech. Even more importantly, I made lifelong friends.

Who has been the biggest influence on your life and what lessons did that person teach you?

When I was younger I used to really enjoy reading manga (comics or graphic novels originating from Japan). I remember this character from the ninja manga Naruto – and its main character, Rock Lee – he had no natural talent, but he became one of the best ninja by working harder than anyone else. This really struck me at the time, and has become fundamental to my ideology. Talent is no match for hard work and perseverance.

What are some of the greatest challenges in your line of work and how did you overcome them?

The greatest challenge I’ve faced so far is not knowing where I fit in and what I wanted to do. Luckily, this challenge revealed itself as an opportunity to explore, which led me to where I am now.

What is the most important thing that can make you successful at your job?

Do something you care about. It’s hard to do your best at something that isn’t meaningful to you.

What are you working on for the future?

For the immediate future I’m working on getting settled in my new home in Atlanta, Georgia. As for the long term future, I’d like it to be a surprise.

What advice would you give graduates?

Don’t limit yourself by thinking your career trajectory has to be a straight line. Sometimes the unexpected deviations from the plan lead to the best places. And stay hydrated.

What do you like doing when you are not working?

I play the mandolin. I’m hoping to also get back on the trapeze and aerial silks once it’s safe to go to the gym.

Anything else you would like to add?

I got a piece of advice once – “don’t mess with dream killers” – and I think that’s important to pass on.

Teame Ersie

Teame Ersie is an Ethiopian Australian, who recently became a Member of The Graduate Union. Teame specialises in the performing and creative arts, beginning his extraordinary contortion and acrobatic arts journey when he was a young boy. He has toured as a solo and ensemble performer across China, Europe, Russia, Australia, New Zealand and the US. We welcome Teame to The Graduate Union and spoke with him recently via an email interview.

Teame Ersie and His Contorted Graduate Pathway

Vital Stats: Qualifications/Accreditations

• Certificate Program – Chura Abugida Fine Art

Association, Mekelle, Ethiopia, 2006 • Certificate III General Education for Adults –

RMIT University, Melbourne, 2011 • Bachelor of Circus Arts – National Institute of

Circus Arts, Swinburne University, Melbourne 2015 • Certificate of Academic Integrity Awareness –

RMIT University, Melbourne, 2020 • Master of Arts (Arts Management) – RMIT

University, Melbourne 2020.

Awards and Recognition

• Business Achievement Award – Afar Regional

Government, Ethiopia, 2009 • Student Achievement Award – Swinburne

University, 2012 • Master of Arts (Arts Management) – recipient of the Dean’s Award for Excellence, RMIT

University, 2020.

What was your educational background? What did you study at university and why did you choose this course?

I completed high school in Ethiopia and became specialised in ground-based physical circus skills, including contortion and human pyramids. In 2009 I started touring internationally. From 2012 to 2015, I undertook a Bachelor of Circus Arts degree at the National Institute of Circus Arts (NICA), Swinburne University. During my three years there, I studied a contemporary-based physical and performance disciplines including Circus Arts, History, Anatomy and Physiology, advanced circus specialties and performance projects, physical movements – both theoretical and practical – along with health and safety in performance, training space and other related courses. The main reason for choosing this course is because from an early age, I was already good with circus skills, and it was important to advance and be qualified. During my professional and employment experience, I learned how managing the arts and artists are important. I was motivated by a good arts manager and noted the challenges faced by the arts or by artists, which led me to study a Master of Arts (Arts Management) at RMIT University.

What did you learn during your tertiary education – not just academically, but what ideas did you form and what perceptions? Did any of your views change significantly when you went to university?

Education has helped me to understand the connections between the arts, people and its core values towards a diverse community and the world. For instance, I learned how the arts can benefit societies beyond entertainment; mainly in health and well-being. My perspective has changed, not only looking at the arts as an entertainment or business resource, but to think deeply about my role as an artist and arts manager to contribute to political, economic and social environments. I have come especially to understand the arts as being one of the most powerful tools of social change, such as promoting equality and inclusivity.

What was your earliest memory and interest of becoming an artist?

I started my circus career when I was about 10 years old, in the city of Mekelle, Tigray region of Ethiopia. I started watching videos of acrobats, and

I was impressed with how human beings could do such extraordinary physical performances. I started asking people who were skilled in acrobatics, and was introduced to some amateur artists. I then learnt very basic skills before joining the local community circus. I was very keen to join, and since that day, I have continued to push my artistic boundaries, both educationally and in physical performance.

What has been your pathway since graduating? What was your first job after graduation and how did that job prepare you for your later positions? Any lessons learnt?

I completed my Master’s Degree in Arts Management in December 2020. I am currently working in a part-time position until June 2021 as a Business Support Officer at the Footscray Community Arts Centre and am looking forward to other potential opportunities.

Did you have any residencies, internships or anything else that ultimately led you to where you are today?

Most of my artistic life I spent performing. Since I arrived in Australia, I was a member of the Catapult Program at St Martins Youth Arts Centre during 2011. Throughout the year, as part of the program, I created, developed and performed my own short theatrical piece for the St Martins ‘Hatched’ Festival, a Youth Art Summit which included researching and designing a program of activities for 18- to 30-yearolds to be delivered by St Martins. I also worked with Multicultural Arts Victoria as a freelance artist while studying at NICA. After graduating, I was selected and secured a contract to work with Franco Dragone Entertainment’s The Dai Show in China for three and half years. I believe everyone I have connected with during my professional experiences has contributed to me becoming who I am today.

What were your goals and what are you ultimately trying to achieve?

The first thing is to make connections with others to help me find work. Based on my qualifications in the performing arts and arts management, and the years of experience I have in theatre and circus performance, my goal is to create a large-scale arts institution/organisation, and play my part to provide and contribute the best artistic experience for artists and the arts community which benefits the health and well-being of society.

Who has been the biggest influence on your life and what lessons did that person teach you?

Both challenges and successes have been my biggest influence. It has let me see and understand the world in different ways, including learning never to give up, knowing I can succeed, despite all the challenges. The people I meet, both in and out of my arts world, have always influenced me in many ways.

What were some of your major milestones?

Settling and living in Australia, graduating from Swinburne University and now graduating with a Master of Arts (Arts Management) from RMIT. I believe having both degrees will enable me to explore my love of the arts, make me a more desirable candidate, and have an opportunity of leaving a better footprint in the arts world.

What have you been most proud of in your career?

My stage performances have enabled me to work and communicate with diverse artists from different backgrounds. Arts is a universal language; the emotional response and respect from the audience – no matter what languages they speak, what religion they believe in, how old they are, what their gender preferences are, what continents they are from or their cultural background – has been a pleasure. Furthermore, I always felt proud knowing that the arts can communicate with all people, and can narrow the differences between people of different cultures and who do not speak the same language. As an artist connecting with new people and sharing emotions has been a privilege and I am proud that I have been through such a journey.

What are some of the greatest challenges in your line of work and how did you overcome them?

Some of the most difficult situations are when you feel excluded because of a lack of cultural and political knowledge. Furthermore, without the requisite language skills, there were times when I wasn’t able to communicate the way I wanted to, which lowers your confidence. However, the arts have helped me to communicate with a diverse range of colleagues at work, school, with audiences and offstage. Even

though I had many other personal challenges, I always manage to see the big picture – the beauty of learning new cultures and the future I hope to have. Because of that, these challenges don’t threaten me permanently and right now I don’t see any of that as a significant issue.

What did you develop during this time – professionally and personally – in terms of your ideas, and did they change?

In general, I have developed creativity, confidence and research skills. Furthermore, I am able to work on projects independently or with minimal support. I have developed good habits of learning and critical thinking. In addition, I have developed the skills of researching, creating and developing company business plans, arts proposals and projects.

What are you working on for the future?

I am looking to advance my professional career development both with individuals and organisations, and work on some interesting and large arts projects. I would like to build my knowledge in any way I can within the arts field, given that the arts industry outlook is still promising despite the COVID-19 pandemic.

What is your next goal? Do you have an ultimate goal that you are working towards?

My goal for 2021 is to find a sustainable job, connect with individuals and industries, and collaborate on some arts projects. I would like to build an arts industry business platform and help to connect artists, arts, industries and audience. I would like to publish some articles in the arts field and improve my academic level by doing a PhD.

What advice would you give graduates?

Improve your opportunities by building networks both locally and internationally. Seek opportunities, apply for awards, residencies, do whatever you are good at and advance your work in a way that makes you unique/essential and raise your profile to the highest level. It is important to stay connected and continue to adapt with researching, reading and writing. If you are an artist, every human needs art for various reasons; to learn new arts, to heal/recover/find relief (especially during this COVID-19 period). Advance your skills for professional development. Find your target community and help in whatever you are good at while continuing to learn: every moment can be an opportunity to learn new things, no matter who you meet or at what level. The world needs a healthy environment, equality, democratic leadership and inclusiveness. As a graduate, be a role model and play your part for the world. Graduates can greatly contribute to the world to become a better place than it is today.

What do you like doing when you are not working?

When I am not working, I like to try new things, such as visiting historical places, hiking, attending live performance (theatre, circus, concerts), exhibitions or galleries, festivals, editing videos, swimming, travel, and other things not related to the arts (I believe it enhances the ability of creativity and imagination).