14 minute read

Alumnus working towards eliminating vaccine-preventable diseases in Pakistan

Mossavir with wife Amna on Graduation day in December 2019 in the foyer of Graduate House.

ALUMNUS WORKING TOWARDS ELIMINATING

Advertisement

VACCINE-PREVENTABLE DISEASES IN PAKISTAN

Muhammad Mossavir (fondly known as Moshi) and wife Amna were former residents at Graduate House. Mossavir was enrolled in the Master of Development Studies course at The University of Melbourne through an Australia Awards Scholarship that offers emerging leaders the opportunity to undertake study, research and professional development with the support of the Australian Government. Such opportunities provided by the Australian Government Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade enable the development of skills, knowledge and networks of individuals to drive change and contribute to development in their own countries and regions, while maintaining strong links to Australia. Mossavir and Amna stayed at Graduate House for two years and returned to Pakistan after his graduation in December 2019. Since then, Mossavir has been working with the World Health Organization (WHO) to provide access to COVID-19 vaccinations in Pakistan. The following story of Mossavir’s work was posted 28th May 2021 at: https://australiaawardspakistan. org/alumnus-working-towards-eliminatingvaccine-preventable-diseases-in-pakistan/ and he kindly shared this also with us. Australia Awards alumnus Muhammad Mossavir Ahmed is working to provide access to COVID-19 vaccination and strengthen childhood immunisation services in Pakistan. He is contributing to this vital work in his role as a Donor Coordinator for the World Health Organization (WHO). As part of the core team working on COVID-19 response initiatives and advisory policies, Mossavir has been instrumental in successfully coordinating and negotiating with donors such as the World Bank, Asian Development Bank, and Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, to mobilise resources that will strengthen immunisation services in Pakistan, particularly the rollout of

FEATURES

the COVID-19 vaccination. With the help of such proposals, negotiations and consultations with donors, Pakistan has been able to secure funding to purchase COVID-19 vaccines or procure vaccines free of cost. “This will help immensely to vaccinate targeted populations against the COVID-19 virus in Pakistan,” Mossavir says of the support that has been secured. “Donors are also funding a significant portion of immunisation for another 11 vaccine-preventable diseases,” he adds. These diseases include tuberculosis, diphtheria, measles, rotavirus and influenza. Importantly, Mossavir developed and submitted Pakistan’s successful application to become a donor-funded member of COVAX (COVID-19 Vaccines Global Access), one of three pillars of the Access to COVID-19 Tools Accelerator. As a COVAX member, Pakistan will receive COVID-19 vaccines for up to 20% of its population free of cost via the COVAX Facility (the global procurement mechanism of COVAX), which is coordinated by Gavi. Mossavir also worked on a request submitted to the COVAX Facility for support for cold chain equipment in Pakistan. Such equipment (including walk-in cold rooms, refrigerators, freezers, passive devices such as vaccine carriers and cold boxes, temperature monitoring devices, and spare parts) is used to keep vaccines at suitable temperatures during all stages of the storage and distribution chain. COVID-19 vaccinations are free of charge for Pakistani citizens, who are able to access the vaccine at Adult Vaccination Counters in all provinces and federated areas across the country. Mossavir played an influential role in developing policies and standard operating procedures for these Vaccination Counters, which were established by the Government of Pakistan with support from WHO. He also developed the National Deployment and Vaccination Plan for COVID-19 vaccinations, along with guidelines and standard operating procedures for the different COVID-19 vaccines that are available. In addition to Mossavir’s recent efforts in COVID-19 vaccine coordination, he is closely involved in the country’s immunisation program to protect children against preventable diseases. “Every day there are hundreds of thousands of children in Pakistan who suffer from vaccinepreventable diseases,” he says. He aims to remain with WHO’s immunisation program to achieve 100% immunisation coverage in Pakistan — and then has his sights set on an even bigger objective: “My plan is to continue working with international and national stakeholders to mobilise resources for achieving universal immunisation coverage.”

To contribute to this ambition of universal immunisation coverage, Mossavir’s work involves a significant degree of coordination and negotiation with WHO’s donors and partners. “My work primarily revolves around donor coordination, donor relations, planning, partnership building and proposal development,” he says. “In addition to this, I have been also involved in research, policy analysis, monitoring and evaluation regarding immunisation services in Pakistan.” Mossavir believes his Australia Awards experience was integral to improving his professional, academic and personal life. “Through this oncein-a-lifetime experience, I was able to study in a well-reputed university, polishing my research, critical thinking and communication skills,” he says about his Scholarship experience. “With the help of this Scholarship, I was also able to work for international organisations like the Australian Red Cross and UNICEF in an international setting,” he adds. “The diversity and interaction with students from across the

Mossavir at the WHO annual immunisation review meeting in March 2021

Mossavir (left) during a joint data quality audit by WHO and partner organisations in May 2021

globe enlightened me to think differently and innovatively. It has boosted my confidence and enabled me to connect with innovative and creative minds.” This experience has contributed to Mossavir’s success in protecting the health of the people of Pakistan through equitable access to the COVID-19 vaccine and childhood immunisation services. Keep up the good work, Moshi!! We here at Graduate House are so proud of you and send our fond regards also to Amna.

Mind time cannot be measured on a watch. Photo by Sergei Karpukhin.

FEATURES PHYSICS EXPLAINS WHY TIME PASSES FASTER AS YOU AGE

By Ephrat Livni

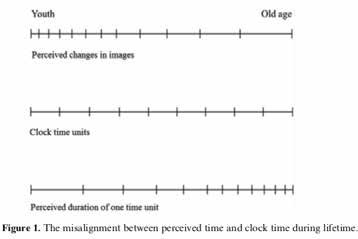

Mind time and clock time are two totally different things. They flow at varying rates. The chronological passage of the hours, days, and years on clocks and calendars is a steady, measurable phenomenon. Yet our perception of time shifts constantly, depending on the activities we’re engaged in, our age, and even how much rest we get. An upcoming paper in the journal European Review by Duke University mechanical engineering professor Adrian Bejan, explains the physics behind changing senses of time and reveals why the years seem to fly by the older we get. (The paper, sent to Quartz by its author, has been peer-reviewed, edited, and approved for publication but a date has not yet been set.) Bejan is obsessed with flow and, basically, believes physics principles can explain everything. He has written extensively about how the principles of flow in physics dictate and explain the movement of abstract concepts, like economics. Last year, he won the Franklin Institute’s Benjamin Franklin Medal for “his pioneering interdisciplinary contributions … and for constructal theory, which predicts natural design and its evolution in engineering, scientific, and social systems.” In his latest paper, he examines the mechanics of the human mind and how these relate to our understanding of time, providing a physical explanation for our changing mental perception as we age.

The mind’s eye

According to Bejan — who reviewed previous studies in a range of fields on time, vision, cognition, and mental processing to reach his conclusion — time as we experience it represents perceived changes in mental stimuli. It’s related to what we see. As physical mental-image processing time and the rapidity of images we take in changes, so does our perception of time. And in some sense, each of us has our own “mind time” unrelated to the passing of hours, days and years on clocks and calendars, which is

FEATURES

affected by the amount of rest we get and other factors. Bejan is the first person to look at time’s passage through this particular lens, he tells Quartz, but his conclusions rest on findings by other scientists who have studied physical and mental processes related to the passage of time. These changes in stimuli give us a sense of time’s passage. He writes: “The present is different from the past because the mental viewing has changed, not because somebody’s clock rings. The “clock time” that unites all the live flow systems, animate and inanimate, is measurable. The day-night period lasts 24 hours on all watches, wall clocks and bell towers. Yet, physical time is not mind time. The time that you perceive is not the same as the time perceived by another.” Time is happening in the mind’s eye. It is related to the number of mental images the brain encounters and organises and the state of our brains as we age. When we get older, the rate at which changes in mental images are perceived decreases because of several transforming physical features, including vision, brain complexity, and later in life, degradation of the pathways that transmit information. And this shift in image processing leads to the sense of time speeding up.

This effect is related to saccadic eye movement. Saccades are unconscious, jerk-like eye movements that occur a few times a second. In between saccades, your eyes fixate and the brain processes the visual information it has received. All of this happens unconsciously, without any effort on your part. In human infants, those fixation periods are shorter than in adults. There’s an inversely proportional relationship between stimuli processing and the sense of time speeding by, Bejan says. So, when you are young and experiencing lots of new stimuli — everything is new — time actually seems to be passing more slowly. As you get older, the production of mental images slows, giving the sense that time passes more rapidly. Fatigue also influences saccades, creating overlaps and pauses in these eye movements that lead to crossed signals. The tired brain can’t transfer the information effectively when it’s simultaneously trying to see and make sense of the visual information. It’s designed to do these things separately. This is what leads to athletes’ poor performance when exhausted. Their processing powers get muddled and their sense of timing is off. They can’t see or respond rapidly to new situations. Another factor in time’s perceived passage is how the brain develops. As the brain and body grow more complex and there are more neural connections, the pathways that information travels are increasingly complicated. They branch like a tree and this change in processing influences our experience of time, according to Bejan.

Finally, brain degradation as we age influences perception. Studies of saccadic eye movements in elderly people show longer latency periods, for example. The time in which the brain processes the visual information gets longer, which makes it more difficult for the elderly to solve complex problems. They “see” more slowly but feel time passing faster, Bejan argues.

Clock time and mind time over a lifetime. The brain’s complexity changes our sense of time.

A lifetime to measure by

Bejan became interested in this topic more than a half century ago. As a young athlete on a prestigious Romanian basketball team, he noticed that time slowed down when he was rested and that this enabled him to perform better. Not only that, he could predict team performance in a game based on the time of day it was scheduled. He tells Quartz: “Early games, at 11am, were poor, a killer; afternoon and evening games were much better. At 11am we were sleepwalking, never mind what each of us did during the night. It became so clear to me that I knew at the start of the season, when the schedule was announced, which games will be bad. Games away, after long trips and bad sleep were poor, home games were better, for the same reason. In addition, I had a great coach who preached constantly that the first duty of the player is to sleep regularly and well, and to live clean.” Now he’s experienced how “mind time” changes over the much longer span of his whole life. “During the past 20 years I noticed how my time is slipping away, faster and faster, and how I am complaining that I have less and less time,” he says. It’s a sentiment he hears echoed by many around him. Still, he notes, we’re not entirely prisoners of time. The clocks will continue to tick strictly, days will go by on the calendar, and the years will seem to fly by ever faster. By following his basketball coach’s advice — sleeping well and living clean — Bejan says we can alter our perceptions. This, in some sense, slows down mind time. * * * Ephrat Livni is a writer and lawyer. She has worked around the world and now reports on government and the Supreme Court from Washington, DC. This article originally appeared in Quartz on 8th January 2019, and is republished here with permission.

The following poem was recited by the author, Aleyna Altinors, a Year 11 student at Sirius College, a Spoken Word Artist (she/ her) and as invited by the Vice-Chancellor of The University of Melbourne at the 18th May 2021 Eid Reception convened by The Melbourne Law School and the Australian Interfaith Society, a potential future student (possibly of Law) at The University of Melbourne.

APPLAUDING WOMEN WITH RESILIENCE

BY ALEYNA ALTINORS

This is for the women with dark skin, cool skin, warm skin, fair skin, white skin, black skin, brown skin, tan skin and all those that lie in between — I need you to know that you’re seen and that we’re proud of you. This is for the women who love who they please and are living authentically, whether it be out in the open or in the closet; for my trans sisters and the fellow queer lovers — I need you to know that you’re seen, and that we’re proud of you. This poem is for the women who wear headscarves, hijabs, the tichel, the abaya, the niqab. The women who wear veils, headbands, caps, snapbacks, hair ties, bandanas, bows, ribbons, wigs, extensions, or none of these — I need you to know that you’re seen and that we’re proud of you. This poem is for the women who work full time, part-time, over time, to the women who work day shifts, night shifts, casual shifts, double shifts, volunteer or do work experience — I need you to know that you’re seen and that we’re proud of you. This is for the women with university degrees, bachelor degrees, diplomas, scholarships, for the women who didn’t complete high school, who didn’t go to university, to the women who chased their dreams, or those whose dreams lead to something else — I need you to know that you’re seen and that we’re proud of you. This poem is for the women who are neurodivergent, for the women who are differently bodied — I need you to know that you’re seen and that we’re proud of you. Whether it comes from our stories or from the media, we know how difficult it is for women to succeed. Politics and an ex-Prime Minister have shown me that it’s alright to shame and silence a woman. To not share disagreement or talk about achievement, because it will be followed with mistreatment from colleagues and opposition. Hollywood picks women like tinder, but it’s not what’s in your bio it’s the way you look. But let’s be honest the corporate world isn’t much different; her resume is perfect but her nose is too far to the left. I don’t really like it. Her talent is perfect but her name is too hard to pronounce. Or she’s just a diversity card. Women being asked to act and look a certain way. Told to achieve or reach a certain limit. Being told from mother to mother, sister to sister, daughter to daughter that THIS is what you need to be like, is part of the problem. We ask our young girls to choose between a red or blue pill. We ask them; Do you want to be confined to society’s idea of you to be accepted? But in return be dispirited? Or work hard to get what you want with the certainty of being told by many that your dreams and goals should be deemed prohibited? This poem isn’t just for women to encourage one another, but for men to encourage the women around them. To tell them they are worth it, that they’re seen, and that you are proud of them. Ladies, our gender and the labels society has placed upon us, should not be an obstacle for you to achieve the great. You need to understand that it’s never too excessive or too late to tell someone that they deserve everything good that comes to them. Be the role model that you wanted, Be the role model you needed, Be the role model you want your siblings and children to have, Or be the role model you still need. Because for young girls like me, words of love and hate stick with us forever. This poem is for the mothers with children, for the brothers with sisters, for the sisters with siblings, fathers with daughters, teachers with youths, employers with employees — Tell the women in your life that you are proud of them, that you see them and that you appreciate them.