8 minute read

Black Light and enlightenment: Fred Wilson’s No Way But This

by Leora Maltz-Leca, Ph.D.

Shakespeare’s tragic drama Othello, set in Venice in the sixteenth century, is one of the few major works of European literature to depict a Black man with nuance and ambiguity. In fact, accomplished and worldly Black men like Othello, whom Shakespeare casts as general in the Venetian army married to a European noblewoman, were a significant presence in Venice and other European cities before and during the Renaissance. In the centuries that followed, however, the presence of Africans in Europe was often dropped from the historical record.

Advertisement

W hen American artist Fred Wilson was chosen to represent the United States at the 50th Venice Biennale in 2003 he turned to Othello, using Renaissance literature and painting to research what turned out to be a robust—but largely erased—history of Africans in Venice, a storied juncture between east and west where for centuries a cosmopolitan and racially diverse culture thrived. As a memorial gesture to these Black communities, Wilson collaborated with glassmakers on the Venetian island of Murano to produce one of the island’s signature, baroque Ca’Rezzonico chandeliers. The Redwood’s chandelier No Way But This (fig. 1) is titled after Othello’s very last line in the play when, having stabbed himself, he declares: “No way but this/ Killing myself, To die upon a kiss.” The quote Wilson selected encapsulates Othello’s desperate sense of entrapment, both by the events which provoked his murder of Desdemona and by a world circumscribed by rigid hierarchies in which being Black was as precarious as it is today.1 Moreover, in the carceral state of the present Othello’s words, and the condition of being ensnared or confined, resonate beyond Shakespeare’s text, portending histories of Black people in the centuries that followed.

to Blackness. At the same time Wilson, a consummate wordsmith, specifies the sculpture as a memorial by placing it in the art historical lineage of a memento mori, the trope of northern European painting that reminded the viewer of the inevitability of death through such symbols as a skull, dying flowers or an hourglass. Wilson substitutes the morbid Latin expression (literally, remember that you will die) with the gentler chandelier mori, his title drawing out the double meaning of mori as “death’ and “Black”. Additionally, the nomenclature of chandelier, which is a word coined in France in the eighteenth century, retrieves a long and specifically European association between light, knowledge and whiteness exemplified in the ideals and imagery of the Siècle des Lumières, that is, the Enlightenment. 3

In No Way But This, Wilson uses glass, a fragile yet incredibly durable material long associated in the Western tradition with light and transparency, as the means to interrogate the metaphor of light as truth, alongside the harmful obverse symbolism it depends on: darkness as duplicity and death.

W ilson titled his first chandelier, the one exhibited as the centerpiece of the U.S. Pavilion in Venice Chandelier Mori: Speak of Me as I Am. As in the Redwood version, the latter part of this title is drawn from Othello’s final speech, where the dying man appeals for truth and fair representation.2 Through this signal quote, the artist highlighted Othello’s terminal request to be portrayed as he was, neither heroically burnished nor maliciously falsified; nor, presumably, simply deleted. In concert with this notion, the monumental chandelier of black glass—an unprecedented color for a Ca’Rezzonico light fixture—works to “bring to light” buried histories of Blackness in Venice. The work’s subtitle, Chandelier Mori, referring to how in Renaissance Venice Africans were called “mori” meaning “dark” in Italian, emphasizes the work as a homage

In No Way But This, Wilson uses glass, a fragile yet incredibly durable material long associated in the Western tradition with light and transparency, as the means to interrogate the metaphor of light as truth, alongside the harmful obverse symbolism it depends on: darkness as duplicity and death. These metaphors, the enduring legacy of the Judeo-Christian tradition, continued to dominate eighteenth-century New England, which modeled itself on European culture. Note how the two institutions of learning that preceded the Redwood in the triad of Colonial learning both seized upon these ideas. Harvard claimed as its motto the snappy “Lux (Light),” and Yale followed with the clarificatory addition “Lux et Veritas” (Light and Truth). Wilson’s No Way But This challenges these powerful visual and epistemological campaigns by creating an object of black light: a gorgeously ornate and luxurious artwork that celebrates opacity and tenebrous reflection. In this way, the artist retools the longstanding equation of light with whiteness and truth, and along with it, the arbitrary and unwarranted linkage of Blackness with falsehood.

The Redwood, chartered in 1747, is America’s Enlightenment institution par excellence: it is the sole secular cultural institution in this country with an unsevered link between the eighteenth century and the present. As such, given this extraordinary but complicated history, the Redwood Contemporary Art Initiative (RCAI) seeks to explore the double history of the Enlightenment, that is, the way in which the most laudable ideals of democracy and liberty coexisted with—or, more cynically, were a rhetoric aimed at diverting attention from—the brutal material realities of the slave trade and abject unfreedom. Rhode Island occupied a central place in this history, and the Redwood was founded with funds donated by a man who owned nearly three hundred enslaved Africans whom he forced to labor on his sugar plantations in Antigua. In this way, the Redwood Library exemplifies this double legacy of the Enlightenment in that its noble ideas of knowledge and education (for some) were made possible by an ignoble reality of slavery and violence.

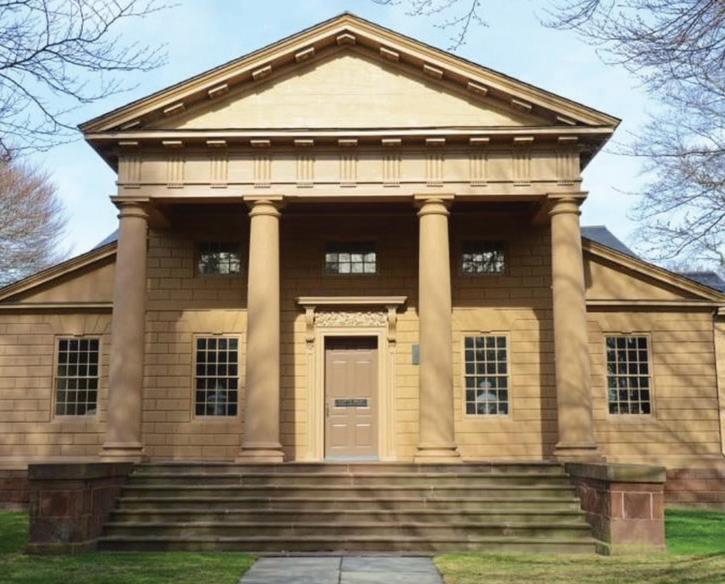

Given the U.S.’s history, Wilson’s memorial to the centuriesold Black communities in Venice is not interesting simply as an isolated instance of one cosmopolitan, multiracial Renaissance city. It points to a larger phenomenon of wholescale obliteration: an entire Eurocentric history of deleting the contributions of African history, mathematics, astronomy, science, art and culture. One starting point was in eighteenth-century Germany, when Johann Joachim Winckelmann and other early founders of modern art history and archaeology denied the profound influence of Egypt and north Africa on Greek language, science and culture, instead projecting a narcissistic image of Aryan blondness onto the ancient Greeks.4 And one place this Enlightenment history of erasure culminated is right here in Newport, RI, with the denial of the very humanity of Black persons through the institution of slavery. It was this denial that allowed Mr. Redwood to make the fortune that funded this library through the means that he did (a library built, ironically, as a Neoclassical temple whose structure is indebted to Egyptian geometry.) The systematic erasure of Black history and Black subjectivity thus forms part of a targeted Enlightenmentera effort of dehumanizing, the rhetorical process bound up with the invention of racial categories of difference, which in turn were necessary to justify the colonial project, mass enslavement, and indigenous genocide.5

A defining element of Wilson’s practice is his investment in the specific context where his work is shown, and the brilliance of his art has often hinged on simple, deft shifts of an object from one location to another.6 Precisely because of Wilson’s emphasis on context, location and the institutional frame as crucial to art’s meaning, the Redwood was committed to permanently displaying Wilson’s chandelier here, in the US’s first public Palladian building. Whereas other iterations of these chandeliers in the US are hung in white box galleries and museums, Wilson’s original Chandelier Mori was made to cast shadows on a Palladian building: the rotunda of the US Pavilion in Venice’s Giardini (fig. 2). Not only does its installation in the Redwood retrieve some of the initial formal sensibilities of the Speak of Me as I Am installation, where shiny black glass was juxtaposed against matte white marble, baroque excess against the austerity of Palladian classicism, but Wilson as an individual was asked to represent “the nation,” at a biennale where the US represents itself to the world beyond. Othello’s (and Wilson’s) demand for “fair representation” reverberated through an exceptionally loaded context of international diplomacy, housed in an institutional architecture loyal to a centuries-old, almost sacred association between Classicism and democracy.

Given that the US pavilion was constructed in the 1930s (as a somewhat anachronistic tribute to eighteenth-century Palladian architecture, and nearly 200 years after the Redwood founders sought to do the same), Wilson’s work serves to highlight the enduring allure of Neoclassicism. But in 2023, is such continuity laudable or does the insistence on an unchanging ideal of classicism represent an utter failure of imagination? This is an image of the US that still asserts itself as a European outpost from which the contributions of African and Indigenous people, then as now, are largely whitewashed. The 2020 Presidential executive order that all Federal buildings in Washington DC must be Neoclassical in style hasn’t helped the association with Palladianism as a static architecture of white male power.7

Twenty-first century US culture, like many before it, might wish to believe it enjoys a “progression” from earlier periods of violence and savagery. Yet Fred Wilson’s nuanced practice opens up an important dialog regarding the uneven back and forth of histories of tolerance. No Way But This points to a long, eclipsed

Acquisition made possible by the generosity of: The Ford Foundation, Mr. Cornelius C. Bond and Ms. Ann E. Blackwell, Ms. Belinda Kielland, Mr. and Mrs. Stephen A. Schwarzman, Mr. and Mrs. Frederick J. Warren.

1 “Certainly, Africans in Italy of the 12th and 13th century had no more stability than they do now, so the point in the Biennale was sort of about that.” Fred Wilson in Fred Wilson: A Conversation with K. Anthony Appiah (New York, NY: PaceWildenstein, 2006): 23.

2Wilson titled his entire exhibition in the U.S. Pavilion of the Venice Biennale in 2003 Speak of Me as I Am, and the chandelier itself Chandelier Mori. But when the chandelier was exhibited subsequently, it was referred to as Speak of Me as I Am: Chandelier Mori history of trade and intellectual exchange between Europe and Africa which existed continuously for centuries, only to be erased, post-Enlightenment, by the invention of capitalist modernity and its key mechanism of accumulation: enslavement. Far from progress, what we see is regress, with the pre-Enlightenment world offering certain models of tolerance and cosmopolitanism that ended with the rule of Enlightenment values of reason, progress and order. Likewise, the resurrection of Neoclassical architectures of power in the 1930s, as in 2020, might be construed as regressive recursions to previous, idealized moments of total white power. Wilson’s sculpture combines a celebration of light with a memorial to death and to the repressed histories of violence and genocide that enabled the wealth and prosperity of the United States. Hung in the Redwood, beneath the streaming light of the oculus (fig. 3), our hope is that this sculpture will open conversations on a more complex concept of light as a spectrum of possibilities, and on history as rife with contradictions, blind spots and opacities.

3The Latin word candere means: to give light, to shine, or to be white.

4For this history, se Martin Bernal, Black Athena: The Afroasiatic Roots of Classical Civilization. Volume I: The Fabrication of Ancient Greece 1785-1985 New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1987).

Leora Maltz-Leca, Ph.D. Associate Professor, Global Contemporary Art Dept. Head, Theory & History of Art & Design, RISD Curator of Contemporary Projects, Redwood Library & Athenæum

5Dehumanizing, defined as the act of depriving a group of people of positive characteristics, forms the basis of genocide, and other murderous acts. See David Livingstone Smith, On Inhumanity: Dehumanization and How to Resist It (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2020).

6For instance, in his iconic 1991 Mining the Museum he relocated objects from the storage space of the Maryland Historical Society to the galleries, displaying two types of local woodwork under the rubric “Cabinetmaking, 1820-1960:” a whipping post surrounded by Chippendale chairs.

7For the 2022 Venice Biennale, Simone Leigh covered the US Pavilion’s Palladian façade with thatch; while German artist Maria Eichhorn’s 2022 installation in the German pavilion called “Relocating A Structure” excavated part of the current pavilion to reveal the additions made by the Nazis in 1938.