5 minute read

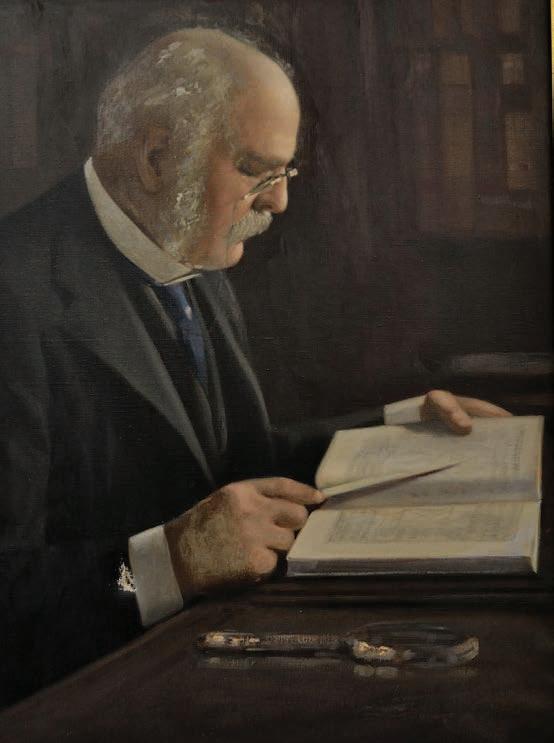

Roderick Terry: The Clergyman Collector Who Helped Shape

Newport’s Literary Legacy

by Michael J. simpson

Advertisement

Roderick Terry was a clergyman who retired to Newport from Manhattan in 1909 and lived there until his death in 1933, becoming in that time among the most significant bibliophile collectors of Gilded Age Newport. A graduate of Yale College in 1870, Terry went on to complete a secondary degree in 1875 from Union Theological Seminary in Manhattan. Around the same time, Terry married Linda Marquand, the daughter of Henry Marquand, a renowned New York philanthropist, art connoisseur, and frequent summer resident of Newport who was President of the Redwood from 1895 to 1902.

In 1912, Terry was elected a Director of the Redwood Library and appointed to the Committee on Books, the beginning of what was to be decades of support and donations to the Library. In 1914, he donated his first sum of books totaling 257 volumes, in addition to giving $500 (equivalent to about $15,000 today) for new book stacks and the salary of the Redwood’s cataloger. Following in his father-in-law’s footsteps, Terry was elected President of the Redwood Library in 1916 “for his services and the thought, time and money he has continuously contributed.” Throughout his tenure, he was financially responsible for restoring the Delivery Room, the Harrison Room, and the Reading Room (now known as the Roderick Terry Reading Room). The original gates from the Redwood estate were installed under his supervision on Redwood Street in 1914. And it was at Terry’s behest that in 1917 Bradford Norman, then the owner of Abraham Redwood’s historic house and property in Portsmouth, agreed to transfer the Summer house designed by Peter Harrison to the Library grounds, where it remains today. Finally, it was Terry who funded the Library’s acquisition of one of the handful of bronze replicas of French eighteenthcentury sculptor Jean-Antoine Houdon’s famed full-length portrait sculpture of George Washington, now outdoors on the South side of the Library.

In 1916, to commemorate the 300th anniversary of William shakespeare’s death, terry loaned to the Redwood a sizable amount of shakespeare works from his private collection for an exhibition that was at the time called “the most remarkable shakespeare exhibit ever held in this country.” copies of the book. As a retired clergyman, Terry’s collection contained other religious ephemera, including a copy of Eliot’s Indian Bible. The latter was the first Bible printed in what would become the United States, and comprised text in both English and Wôpanâak, the language of the Wampanoag people. Both the Morgan and Brown collections included this same edition. Terry’s holdings of Shakespeare exceeded those of both Brown and Morgan: while Terry owned a 1622 first edition of The Tragedy of Othello, Morgan’s collection has no early editions of the tragedy, and Brown only has a copy published in 1630.

It is nonetheless Terry’s role as a bibliophile supporter of the Redwood upon which his legacy should logically rest. In 1916, to commemorate the 300th anniversary of William Shakespeare’s death, Terry loaned to the Redwood a sizable amount of Shakespeare works from his private collection for an exhibition that was at the time called “the most remarkable Shakespeare exhibit ever held in this country.” The American Art Association catalogues of the posthumous sale of his book collection attest to the superlative quality of the Terry materials displayed at the Library: first editions of Shakespeare’s Poems (1640) and The Tragedy of Othello (1622), second editions of A Midsummer Night’s Dream (1600), King Lear (1608), and The Merry Wives of Windsor (1619).

The Shakespeare exhibition was the Redwood’s first devoted to rare books, and the first of many subsequent shows drawn from Terry’s collection. In 1927, the library held an event to commemorate the 200th anniversary of James Franklin’s—the older brother of Benjamin—establishment of a printing industry in Newport. This exhibit held many “valuable specimens of early Newport printing.” In 1929, Terry loaned items for an “exhibition of pictures, broadsides, maps, and letters in commemoration of the 150th anniversary of the Battle of Rhode Island.” A second exhibition that year, also based on loans from Terry, included “original letters, manuscript poems, and autographs of some of the famous early American writers.” In 1932, Terry loaned several valuable books from his collection to show “an example of the growth and progress of the printer,” an exhibition—Terry’s last—that was deemed at the time as “one of the most important and interesting exhibitions ever shown at the library.” Later, in 1931, in support of Terry’s special interest in the library, his wife Linda Marquand Terry “very kindly loaned a collection of handsome laces and fans.” These presentations make clear not only Terry’s devotion to the Redwood, but also his and his family’s commitment to Newport’s history and public history.

In the context of the region and era, terry’s personal book collection of Western literature from both europe and the Americas was of particular significance. Indeed, his collections are comparable to the vast collections of far better-known individuals such as John Carter Brown (1797-1874) or J.P. Morgan (1837-1913).

The first volume of the American Art Association’s catalogs of the Terry sale provides a telling measure of his collection: “Over half a century ago he began to lay the foundations for a private library which, during ensuing decades, grew to be one of the most remarkable collections in this country.” Among Terry’s collecting passions was also historic autographs, some still remaining in the Redwood’s Special Collections. The auction included signatures of George Washington, Rhode Island General Nathanael Greene, and “a complete set of the autographs of the Signers of the Declaration of Independence,” which included rare signatures of Button Gwinnett of Georgia, and Thomas Lynch Jr., of South Carolina. The collection also included autographs from noteworthy figures like authors Charlotte Brontë, Lord Byron, Edgar Allan Poe, and astronomer Galileo Galilei. Final revenues from the sale certify Terry’s eye for quality and attest to his indelible mark on Newport’s literary legacy: according to the Newport Daily News, the sale of Terry’s “rare books, manuscripts, and autographs” generated $167,876, or about $3.8 million today.

Michael J. Simpson holds graduate degrees in History from new York University and Brown University, and is now an Adjunct Professor of History at Johnson & Wales University in Providence. He is also the founder of On This Day in Rhode Island History

In the context of the region and era, Terry’s personal book collection of Western literature from both Europe and the Americas was of particular significance. Indeed, his collections are comparable to the vast collections of far better-known individuals such as John Carter Brown (1797-1874) or J.P. Morgan (18371913). For example, while Brown’s collection contained only one leaf of the Gutenberg Bible, Terry’s contained twenty-four leaves, encapsulating the entire Book of Genesis. On the other hand, Morgan’s is the only collection in the world to have three complete

Sources consulted:

American Art Association, The Library of the Late Rev. Dr. Roderick Terry of Newport, Rhode Island, Vol. 1 (American Art Assoc., New York, 1934).

“Folders of letters and documents relating to Dr. Roderick Terry” [1907-1932], B.102F.2, Newport Historical Society.

Mayer, Lloyd M., “In Memory of Reverend Roderick Terry,” Bulletin of the Newport Historical Society, No. 91, (Apr 1934).

Roderick Terry Collection, Redwood Library and Athenæum.