25 minute read

GIFTS UNASKED FOR

The 2020 Most Powerful Women talk about finding their truths, building careers and accepting the ‘in spite of’ people in our lives

Advertisement

he teams at the Post and Nfocus teamed

T up again this year to organize Most Powerful Women, convening a group of outstanding leaders to tell their stories of leadership, entrepreneurship and career growth. is year’s event — which was presented by PNC Bank and also sponsored by istle Farms and Postmates — featured Nashville Entrepreneur Center CEO Jane Allen, e Cupcake Collection founder Mignon Francois, Nashville State Community College President Shanna Jackson and istle Farms founder Becca Stevens. e quartet gathered at the LA Jackson bar atop the ompson Hotel in e Gulch to share their experiences, insights and advice with each other and more than 100 video attendees. On the following pages are excerpts, edited for brevity and clarity, from their chat, which was moderated by Kelly Sutton and delivered to those watching from their homes and o ces by Bright Event Productions.

SUTTON: Mignon, what was that rst step like for you in 2008 building e Cupcake Collection?

FRANCOIS: What people need to know is that you’re not going to have everything and you don’t need to have everything. You start where you are and that’s enough for right now. It’s about having just enough light for the step that I’m on.

Yeah, I was going to need a big, gigantic mixer and a giant walk-in freezer and all that other stu . But it was a dorm-sized fridge and a KitchenAid mixer that I opened my store with. And that was 12 years ago.

Start where you are with what you have. And that’s enough to serve just today. Tomorrow, we’ll think about something di erent. Today, we’re going to worry about just a dorm-sized refrigerator. SUTTON: Becca, let’s talk about istle Farms and where you’ve come from. Did you ever imagine it would become what it is today?

STEVENS: I’m probably surprised it’s not bigger. Because I think it’s a really good idea. And I totally relate to the idea of ‘Just start where you are and you keep going.’ For us, that meant one house in Sylvan Park and opening this bath and body care company because women weren’t getting hired. ere was no Entrepreneur Center; there was none of that going on. So what we wanted to do was just starting making it so we made candles in a pot. ey’re not that hard to make — but ours are the highest-quality not-hardto-make products.

I also think community is the whole thing. It’s the entity that holds us up, the entity that holds us accountable. SUTTON: Shanna, Becca mentioned community and especially women. ere are not many women in the position you’re in. How did you nd a community in being the president of a college?

JACKSON: When I was a little girl, I intended to be the rst black female president of the United States. So I’ve always aspired to be a leader. I moved to Nashville to work for the Pillsbury company in Murfreesboro. So being a college president at the age of 20 was not a thought.

I had an opportunity to teach and the community part really came in because I saw the power of education in action. Being with students who weren’t raised in a two-parent home with college-educated parents really changed things for me. So when I got into the community college system in 2000, I realized I wanted to be a president. I didn’t see many women — there

were no African-American women presidents — but I desired to be that and had a lot of wonderful sponsors and mentors in my life to make that possible. I don’t have a traditional journey. A lot of people go faculty, then dean, vice president of academic a airs. I did a really crazy journey and I think that’s because I led with what was really important to me: Our community and making it better through education.

SUTTON: It seems like that common thread is that sense of community, the idea that no one super successful got there without someone helping them along. Is there somebody that you remember for that or an instance when someone whispered something in your ear and it clicked and it all came together?

ALLEN: For me, it’s a lot of people. After I graduated law school, I had the bene t of clerking for an amazing human being, Edward Johnstone, who was a federal court judge in Western Kentucky. He was probably my rst professional mentor. He really talked to me about keeping the playing eld level, access for all, and just doing something that you love and feel really good about.

And then I’m blessed to be married to a man who is probably one of the brightest people I know and who helps keep me in line. I’ll have ideas and he’ll say, “Really, Jane?” But then when I was thinking about Counsel On Call, it was him coming to me saying, “You’re doing something that really can transform the legal profession. Why not now?” And I’d say, “Well, we have three little kids under 3 years old.” He gave me the courage and, quite frankly, maybe pushed me out there a little bit and has continued to do so each day.

Even with the Entrepreneur Center, it was me saying, “I know I’m going to be ‘retired’…” And he said, “Are you kidding me? Go do it. Make an impact. Have a positive impact.”

SUTTON: Mignon, what about you?

FRANCOIS: I agree with you, Jane. How do you say it’s just one person? You have to look at the journey and see where you’re going to pick that from. But if I was going to pick one, I think it would be my neighbor, Joanie Dixon. She was like the mayor of our town, of Germantown. She had come over to my house and said, “Listen, those cupcakes that you’re making? I’m going to give them to all my

MIGNON FRANCOIS

clients. So just get in there and start making them and when you get some, I’ll pay you.”

But I didn’t have any money. As a matter of fact: e day she knocked on my door and asked me for them, I was sitting in my house with no electricity because I couldn’t a ord it. Now, Joanie has this way about her that makes you feel like you have to do what she says. And so I accepted her “order,” closed the door and had a conversation with the Lord. “How are you giving me this opportunity when I have no money to take it?” And I heard God say, “But I feed birds and they don’t toil for anything.”

So I put on my shoes, took the only ve dollars I had, walked to the store and started working on that order. And I had enough to give her something that she could pay me for. And I turned that $5 into $60 that day. And then to $600 by the end of the week. at’s the same money I’ve been ipping for the last 12 years. at’s why I want people to know you don’t have to have everything. You just have to have enough faith to believe. All you need is somebody to believe, to give you some of their faith currency.

JACKSON: I just want to say this for our leaders: One of the things we do on our journeys is thinking that we have to check every box. When I went to Columbia State, there was a president there — she’s still there, Dr. Janet Smith — who pushed me. And sometimes you need people to push you.

I kept thinking I need to go from this position to that position. ere was a presidency open — not Nashville State — and she said, “You should apply.” And I said, “Oh no, I don’t want to apply for that. I’m not ready yet.” And she let it go. But she eventually took me to lunch — which she never did. And she got in my face and told me, “You said you wanted to be a president. You need to put your name in the hat.” And I was actually a nalist. I wasn’t selected but that gave me the sense of con dence that I was ready for the next step.

So I just want to encourage everyone out there that, sometimes we look at a list of 10 things and, as women, we think we have to check every box. Men see two, they check it o and they apply. So apply! Whatever it is you’re thinking about doing right now, if you have a few things checked o that list, you should put your name in the hat.

STEVENS: What I would say, too, is that there are also people “in spite of.” ere are mentors and people who propel you but there are also some people that, because of the brokenness you experienced, helped propel you, too. I do believe that brokenness can be transformative in our lives, into something that is about compassion and generosity and leadership. e closer we can get to seeing those as gifts in our lives — gifts we never would have asked for... But I know part of the reason I’m doing what I’m doing is not because people were so nice. It’s that some people were so abusive and I understood the need for sanctuary and safety for folks.

FRANCOIS: I agree. I always like to encourage people to know that what’s happening to you is actually happening for you. Because if the biblical principle is true that all things work together for your good, then that means all things. Not just some things at some times. When you ever ask successful people about their journeys, you never hear them say, “Oh, I wouldn’t have gone through that.” e biggest thing about this is that it’s hard. If it wasn’t hard, everybody would do it!

ALLEN: at’s one thing I’ve been saying with everything going on with the pandemic. ere’s never been a better time to be an entrepreneur. Di cult times are where problems need to be solved and people are open for disruption.

Di cult times make you tougher and they make you sharper. Living through Sept. 11 and living through 2008, it made us a better company and it made me a better leader. And you’re right: Sometimes, you have to listen to the haters a little bit, too. Because there are going to be people who put you in a box or try to tell you what you can’t do instead of pushing you forward.

On disruption and regrets

SUTTON: Let’s talk some more about what it looks like to run a business, to be successful, in the age of COVID. What have you had to change and what do you feel is going to come out of this?

ALLEN: Innovation is going to drive us out of this — and that’s what we’re seeing. Yesterday, we had our rst team meeting in person to talk about the last six months and what we’re going to do moving forward. And one of the people said, “We’re a better organization.” rough di cult times, you’re able to do some self-re ecting instead of run, run, run. And you’re able to look at what’s really important.

What are the resources entrepreneurs need that we can surround them with to increase their probability of success? Let’s get to that. And let’s make sure we’re there for the entire entrepreneurial community and that we really are leveling the playing eld. As an organization, yes, we’ve had to make some hard choices. Yes, we have budgetary issues. But we’re doing exactly what our entrepreneurs are doing. We are living it side by side, day by day. SUTTON: Mignon, you had the double wham-

JANE ALLEN

my. You had the tornado right on your back porch and then the pandemic. How has your business survived and what have you had to do?

FRANCOIS: It was a blessing for me that the tornado came rst. We were already disrupted before the pandemic came to Nashville. We had four major trees laying on our house. We had probably the oldest magnolia in the neighborhood on our porch and it stopped anyone from coming down Sixth Avenue North — except for the people who needed cupcakes. Because they were crawling over the trees and saying, “Is there anything inside?” I knew we had to get a way to get the store up and running.

So I jumped on social media and said, “We need a place.” And other bakers and other caterers started o ering me their kitchens. And someone had seen how I had been helping other people during the tornado got on the phone with his company and Taziki’s and said, “How can we help Mignon do pop-ups?”

I just wanted ve pop-up shops. ey turned it into nine locations. I think there was only one in the area that we weren’t in. Had the tornado not happened, there would’ve been so much red tape that would’ve caused us not to do it. “Oh, that would be great if we could gure it out.” Well, people are guring out things that they normally wouldn’t take the time to gure out.

It kept us in business. We were trying to gure out after the world started coming back if we would be able to continue to do this. And we were going over the nancials and my CFO said, “You’re crazy if you stop. I don’t care if you have to bring them, Mignon Francois. You will continue to have cupcakes in other cafes.”

It’s like you said, Jane: is has been the mother of innovation and invention. People are opening doors that might have otherwise been shut. I’m so grateful that it took a tornado for us to realize that we needed to partner.

SUTTON: Because the world looks do di erent right now, Becca, how does that impact what you’re seeing?

STEVENS: I’ve been thinking about the word “disruption.” It comes from the word “ruption,” something that’s already broken. So disruption is basically a time to put stu back together.

Interpreting what’s going on around us is one of our jobs as leaders. We don’t have to

understand what COVID is. We don’t have to understand the res. We don’t have to understand the tornadoes and all that. But we get to interpret what is happening around that in our communities and helping people through that. And if you are doing that well and you’re not grieving, you’re not paying attention. ere’s plenty to grieve — whether it’s the loss of lives or the loss of property.

So for us to interpret and re-interpret and put things back together through a disruption is critical. It’s also being a voice saying, “We’re not just pivoting. We are digging deep to our roots and we are growing something and we are going to get through it. e pandemic is no time to quit.” And you’re that voice helping people go through that.

SUTTON: Before we get to our audience’s questions, I have one more for you all. I believe that everything everyone does comes from a place of their truth, that you have to nd your truth before you go on on your journey and know what’s out there for you. How did you all nd your truth? Shanna?

JACKSON: Really, in that classroom. I can tell you that it was never a thought that I would have a career in education. I married my husband and we moved to Knoxville and I didn’t have a job. I answered that ad and it forever changed my life.

I truly always wanted to be a leader and make a di erence but never knew in what area that might be. at’s when I discovered education is powerful. My dad was part of a big family and he was the rst to go to college. Education meant everything to him and I wanted to mean everything to the students. ey may not nish to get a degree but if they come to Nashville State and I can make a di erence in their lives… And it’s not just the student. I like to say it changes their family. It changes their community.

SUTTON: Jane, how did you nd your truth?

ALLEN: at’s a great question and I don’t know that I’ve found my truth. I think the truth continues to evolve and sometimes, you nd your truth by looking backwards. And like you, Shanna, I had a mother that made me believe I could be anything in the world. I remember saying I wanted to drop out of college to be Joan Jett. And she was like, “OK, girlfriend. What do we need to do make that happen?” She didn’t tell me I was a terrible singer.

I remember going to Byron Trauger and saying to him, “I’ve got this little seed inside of me. And I keep covering it up with dirt but it keeps sprouting. And I think that, if I don’t follow up on that, in ve to 10 years, I’m going to regret it. But would you hire me back if I fail?” And he said yes, so that gave me the con dence. And I will say that, when I had the company, every day I felt like I was living out the purpose. I started my day with a prayer and I felt that I was living out a purpose. And then I sell the company and, all of a sudden, I’m in the wilderness and I keep waiting for the burning bush. en, when the EC knocked, I started waking up at night thinking, “Oh, I wondered if they’ve tried this or if they’ve tried that.” And then I went from “they” to “we,” and I said, “OK, I think this is part of it.” So what is my truth? It keeps evolving and I hope I keep being a better person and I keep being more compassionate and empathetic and kind and walking people to the table.

SUTTON: Mignon, how did you nd your truth?

SHANNA JACKSON

FRANCOIS: I think I found it in trying. I didn’t know how to bake — not even out of a box. All the recipes are mine and they’re award-winning — and I didn’t know how to bake.

You know how people say listen to your heart? Your heart really exists right here around your gut. And I began to learn that it’s a muscle and that when you exercise it, it’s just like any other muscle. It gets stronger and it speaks louder. And if you just try it, you will realize that that’s the voice that’s leading you. at was the voice that said, “Get your shoes on.” at’s why I want people to know you don’t have to have enough. You don’t have to have a computer; you can use a tablet. You don’t have to have a tablet; you can use your phone. You don’t have to have a phone; you can still use paper. I had to learn that I had to go through something and I had to listen to that voice.

SUTTON: OK, so we’re going to get to the questions. Here’s one: What is the one regret that you have?

STEVENS: Mine is easy. I wish I had dreamed bigger sooner. I was never afraid of success. I was held back by fear of failure sometimes. I didn’t want to jeopardize what was already there to grow.

What we have is a big idea around a global movement for women’s freedom. And it took me a long time to be willing to dream bigger and I wish I had done that sooner. I don’t think it’s a regret but looking back at the exponential growth we’ve had, that growth could have started a little bit sooner and more women could’ve come and been a part of the community.

JACKSON: I don’t think mine is professional; it’s more personal. I think all of us have that mother’s guilt. I wish I could have spent more time having lunch with my son when he was in elementary school. He would say, “Everybody else’s mom comes to have lunch with them.” I worked a little too far away and would literally have to take half a day to have lunch with him.

I tried to make every ball game and I still do. He’s in college and we’ve been driving eight hours to go to games. So I don’t think he had a life without his mom because I was always there. But a few more lunches during elementary school… I have some regrets over that.

BECCA STEVENS

SUTTON: at just went to my heart because mine just started middle school and last year was the last chance to do that. So I understand that. Jane, what about you?

ALLEN: I’ve tried to live with the motto, “Don’t live with regrets.” When my mother fell ill, I jumped on a plane to get to my mom. But in doing so, you’re leaving behind your husband and children. I say I have ve children in my life and the whiniest and the neediest was the company. And so while I think that our children and my husband have been a priority in my life, I don’t know that I’ve always shown that.

FRANCOIS: I heard Fantasia sing a song. She said, “It was necessary.” What I have decided and understand is that there are no mistakes, that we don’t know the plan for our lives anyway. We go about our lives making plans for things that we have no clue of. We think that we’re doing things wrong but they’re all just a part of the ultimate plan for us to get from where we are to where we’re supposed to be.

So it’s hard for me to say what are regrets because I see it all as necessary.

SUTTON: I love that. A question I have is: How do you know when it’s time to take that next step? How do you know when it’s time to hire someone or open another location?

ALLEN: at’s what we do at the Entrepreneur Center. Part of that is through the programming and part of it is through mentoring and advising. We have a group of successful entrepreneurs who have all exited and who give their time to help the next generation and it creates this circle of giving. We’ve all been in their shoes — whether you’re at $100,000 trying to get to $500,000 or $500,000 to $1 million or $1 million to $5 million.

It really is about connecting them so that they hear more than one voice [and] surrounding them with people that are not just going to be “yes” people. ey’re people who will ask you di cult questions and push you and make you feel uncomfortable.

STEVENS: At istle Farms, it is that but it’s a little bit di erent. When Forbes put out an article on us not that long ago, they said the reason we’re successful is that we’re a mission with a business, not a business with a mission. I’ve started really talking about the way we do stu and the organizations we are partnered with that it’s a justice enterprise and not a social enterprise. And when we say “justice enterprise,” the mission is the workforce.

I didn’t start by saying, “I want to hire some women because I really want to make these candles.” e women were there and it happened that candles or essential oils were the products that we were o ering. When the mission is the driving force for the business, those questions get answered kind of organically.

JACKSON: I want to take it from the perspective of leadership and professional development and growth and not being the entrepreneur. Both of you have hit on something I think is important. I’m sure you all have been asked, “Will you mentor me?” And because I have been mentored and still have sponsors, I always say yes and try to make myself available. But I’m always telling them to let the work drive them, not the money.

Some people will say, “I have this degree and that degree so I should be making X by now.” And I’ll say, ”But you’re focused on the title and the money. You’re not focused on the work. So let’s get the work right. Let’s get the passion and the mission and all those other things will come.” I was always focused on that. It was never about the paycheck.

So I want people to know that if you’re setting yourself on a timeline — “In three years, I want to be here and in ve years, I ought to be there” — I think you’re setting yourself up for failure. It happens organically and I feel like that’s been my career. It was always about the work and what I was contributing to the mission and not about how much did the next job pay.

YOU SHOULD KNOW

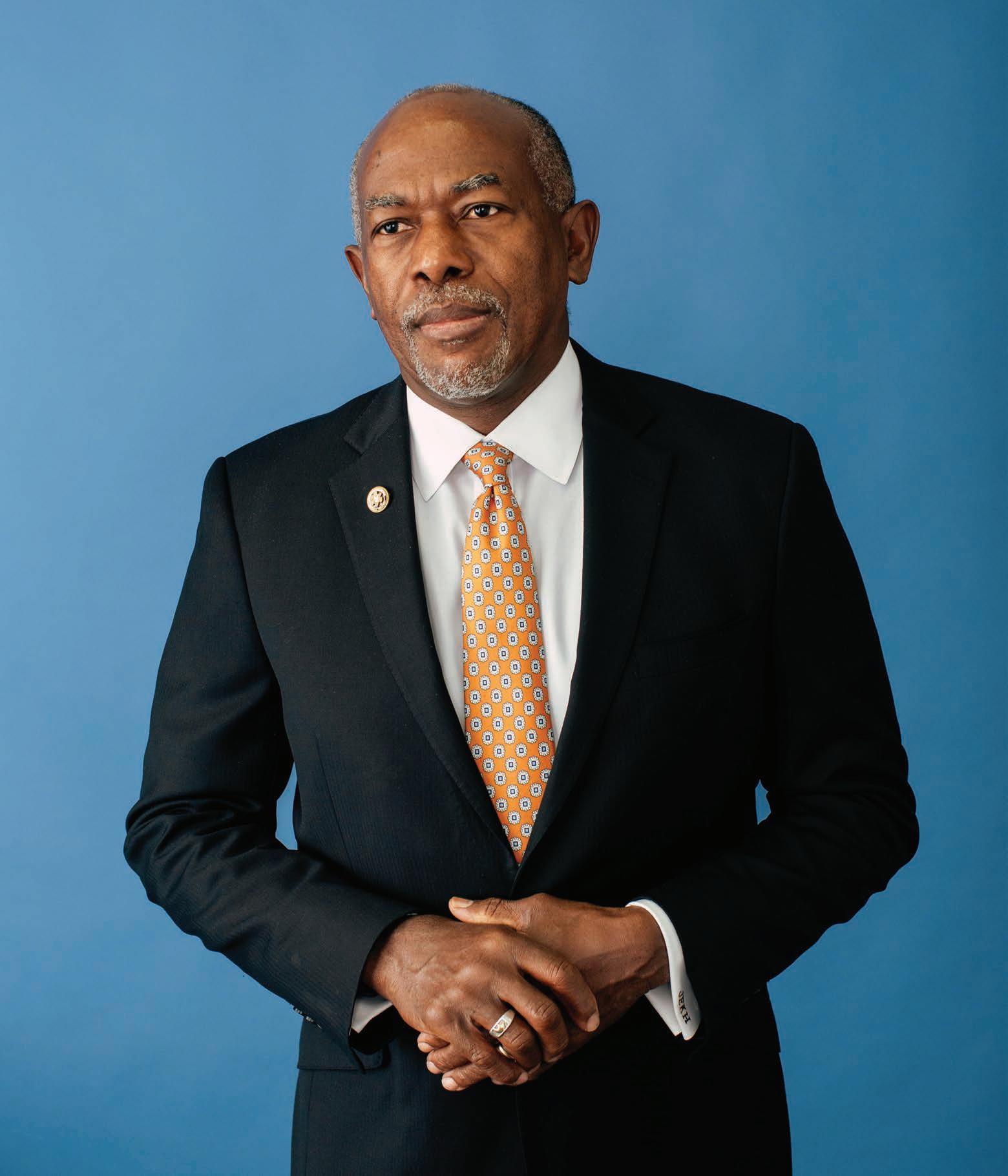

Jason Ridgel

Distiller of Guidance creates whiskey to add ‘flair’ to state liquor lineup

NASHVILLE BUSINESSMAN and distiller Jason Ridgel takes a distinctive approach to how he views competition from fellow whiskey makers.

“I measure success by how many other brands

I can help get in the market,” he says.

The owner of Guidance, a whiskey brand that continues to draw positive attention with recently accelerated sales, knows that a tight-knit local community of makers of spirits is helpful to all involved. And many will sip on a double to that. “My goal by 2021 is to be drinking only my friends' liquor,” Ridgel says. “When I walk into a place and I see the brands from people I know on the back bar, then I will have done my job.”

Ridgel (pronounced Rih-GEL) launched Guidance in 2018. He still has no employees but notes his friends and family have been paramount in helping him grow the business.

When asked “Why whiskey?” he responds with a chuckle: “Because I couldn’t drink sake every day.”

As in many other parts of the economy, Black Americans aren't well represented in the ranks of distillers, vintners and brewers. In addition to the challenges of finding the capital to launch a business in the alcoholic beverage sector, cultural and social considerations can be used to explain the dearth. But Ridgel points to the future and not the past. He notes there is a movement involving Americans of color — often in prominent roles — working within the alcoholic beverage-making and distributing sectors.

In fact, Guidance recently finalized an agreement with Louisville-based distributor Legacy Wine and Spirits, which is African-American owned. Legacy has helped land Guidance whiskey into 10 retailers in Kentucky. Overall, Guidance is available in 50 retail locations in multiple states courtesy of five other distributors. Today, and in addition to Tennessee and Kentucky, the whiskey is available in stores in California, Florida, Georgia, Illinois, Iowa and New York. Consumers in 43 states can buy the beverage online.

It’s not surprising, in some respects, that Ridgel founded Guidance. The Alabama native and Tennessee State University graduate, now 41, has been entrepreneurial for some time. At 23, he founded his first business, a janitorial services company. He later owned Jusco Medical, a medical equipment sales business. However, Ridgel’s interest in whiskey was born in 2016, the point at which he realized there could be a chance to alter folks’ perceptions and definition of whiskey from the Volunteer State.

“Tennessee whiskey has always been respected but it needed some additional flair,” he says.

When Ridgel launched Guidance two years ago, he did so with his own money and no financial support. He selected the moniker “Guidance” to pay tribute to ancestors who have handed down positive contributions and support over generations.

And, of course, at that early point of his brand’s evolution, he needed to find a distillery partner, and did so with Iowa-based Dehner Distillery.

“I found out about Dehner from my friend Stacey Thomas, a wine broker,” he explains.

As to the whiskey itself, Guidance is a combination of three grains: 88 percent corn, 10 percent rye and 2 percent malted barley. Aged for 24 months, Guidance o ers a flavor that is, as the brand’s website notes, “dominated by smooth front-end vanilla with a light and smooth experience in the middle” followed by a “long, smoky finish.”

Ridgel said he is encouraged that fellow Black-owned whiskey maker Nearest Green Distillery continues to make progress. In June, that operation and Jack Daniel’s Distillery announced the Nearest & Jack Advancement Initiative to increase diversity within the U.S. spirits making industry.

“The progress being made to diversify the spirits industry is encouraging,” he says. “I’m excited to see how the future unfolds.” > WILLIAM WILLIAMS

COMING MARCH 2021

19 sectors, 400+ area leaders Check out our extensive list of the region’s most influential business, political and civic leaders in our Spring magazine.

THANK YOU FOR ATTENDING

Thanks again to our terrifi c Most Powerful Women panelists — Jane Allen, Mignon Francois, Shanna Jackson and Becca Stevens — and our moderator, Kelly Sutton. We also want to send our congratulations again to this year’s Nfocus Model Behavior honorees.

Emerald Mitchell Tina Doniger Karen Moore Martha Silva Mary Flipse

Nancy Keil

SPONSORS

Sara Morgan Perri duGard Owens Tara Scarlett Julieanna Huddle

THANK YOU TO OUR SPONSORS AND PARTNERS!

PRESENTING SPONSORS PARTNERS