7 minute read

DON’T FORGET NORTH NASHVILLE

The district received a flurry of support after the tornado. Will the long-promised revitalization finally follow?

BY MEGAN SELING

Advertisement

t seemed as though North Nashville

I had the world’s attention in the weeks following the March 3 tornado. Large plots of the area were destroyed. Homes and businesses were attened, trees were torn from the ground and scattered across roads like piles of sticks. e power remained out for several nights of below-freezing weather as Nashville Electric Service struggled to make repairs on many streets blocked by debris.

So when grassroots organization Gideon’s Army put out the call for volunteers and donations, hundreds of helpers ocked to the area to bring food, clothing, tents, sleeping bags, generators, tarps and rope. Others showed up with power tools, rakes and shovels, o ering to help remove branches and debris from homes and yards. Community organizing group Hands on Nashville got so many volunteer signups they were turning folks away some days, and, at one point, Gideon’s Army received so many donations they were forced to pause intake so their team could catch up on sorting and distribution. (Gideon’s Army has since used many of those remaining donations to found the pop-up shop Gids City, a by-appointment shopping experience that gives residents in the 37208 ZIP code the opportunity to shop for at no cost for new clothes, shoes and accessories.) e historic, predominantly Black neighborhood and Nashville’s unifying e orts to begin to clean up its estimated $30 million to $50 million in damages were featured in e New York Times and on ABC News. But that incredible display of goodwill was only a small bandage —both for the storm damage and for the decades that Nashville has neglected the people of North Nashville. In the 1960s, the government designed Interstate 40 to cut directly through the neighborhood. After a long legal battle, the highway was approved and built, severing much of North Nashville from downtown and splitting its main artery, Jefferson Street.

Developer Lee Molette II has lived in Nashville for 30 years — last fall he co-founded the Nashville Business Alliance Political Action Committee to advocate for minority- and women-owned businesses — and when he talks about just how badly the interstate negatively impacted North Nashville, he likens the area to a wounded body. ere was a time when it was whole, healthy. en I-40 cut through like a knife.

“To the naked eye, it doesn’t seem like a big deal,” Molette tells the Post. “But to the people living there, you essentially cut o the arteries. Now there’s no real exit that drops you right on Je erson Street. [Developers] cut into people’s land, people lost parts of their lots and were given pennies on the dollar. And when you cut o the blood ow, obviously the organs stop working. e businesses on Je erson Street lost business. ey weren’t able to thrive and compete like they used to.”

And while all the support in the spring was nice, Molette says he still hasn’t seen any e ort to create lasting change from outside supporters.

“ e sad thing is, if you talk to various mayors, they’ll talk about, ‘Hey, we’re gonna do something over there, we’re gonna do something over there.’ But when the project comes, it’s so much BS and bureaucracy that nothing happens. And then they’ll focus in and say, ‘We’re only going to do one project.’

“No,” he adds with an exasperated laugh. “You have a whole damn street to get to!”

Indeed, mayors have made attempts. In 2015, Karl Dean proposed relocating the Metro Nashville Police Department headquarters from downtown to Je erson Street, but the tone-deaf proposal was rejected by Metro Council months later. Two years later, Megan Barry announced a partnership with the Nashville Civic Design Center to install a 0.35-acre pocket park at Jefferson Street and 16th Avenue North. At the time, she said, “I’m excited for the opportunity to reactivate Je erson Street, a corridor that has so much historic and cultural signi cance to our city.” Earlier this year, it was announced the park would be named after Kossie Gardner Sr., but construction has not yet been completed.

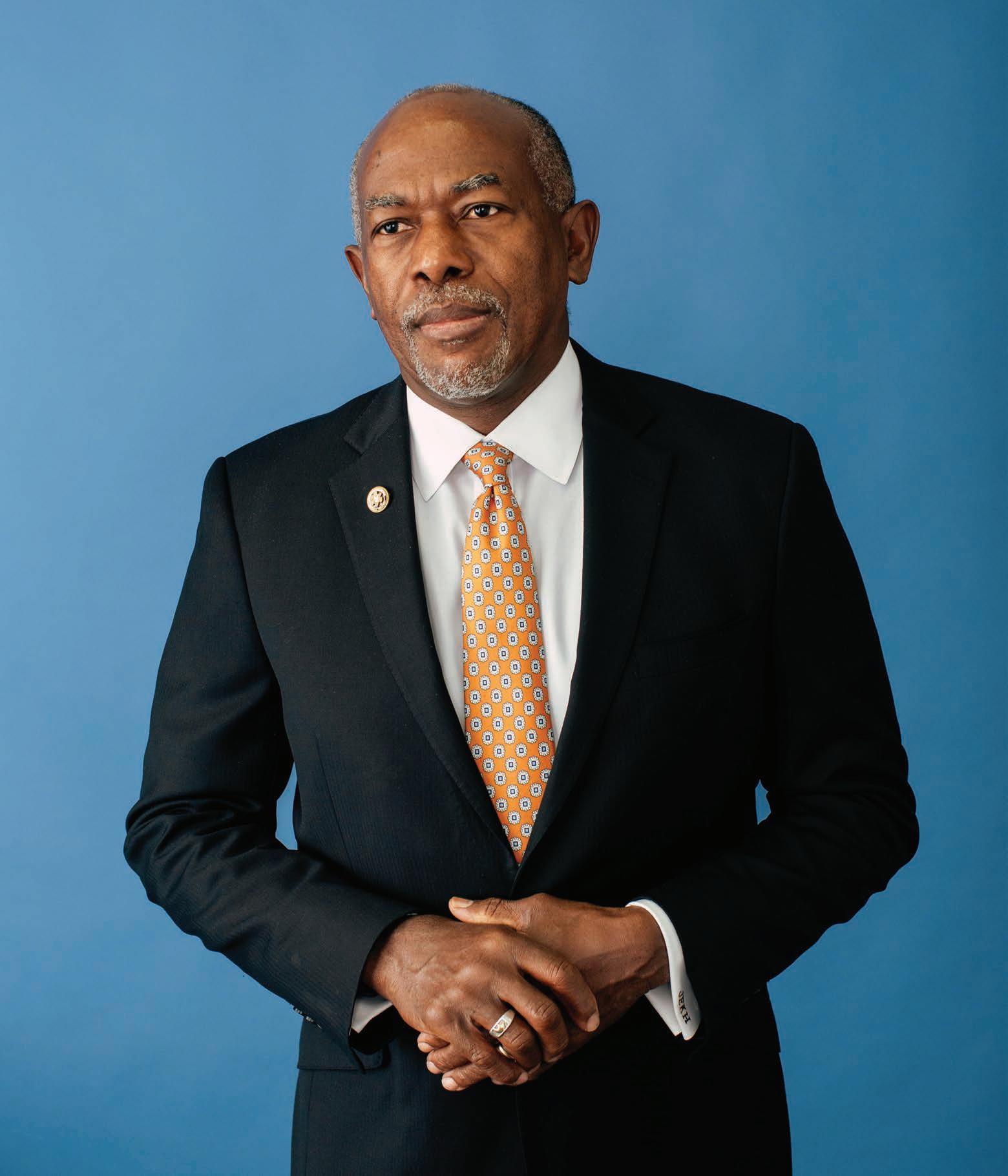

LEE MOLETTE II, NASHVILLE BUSINESS ALLIANCE POLITICAL ACTION COMMITTEE

More recently, in September, Mayor John Cooper released a draft of a $1.5 billion transit plan that includes, among other things, a new transit center in North Nashville as well as a “cap” over part of I-40 near Je erson Street. e latter is not a new idea: City leaders have discussed the possibility for years. e cap, drawn up by the Nashville Civic Design Center, would be a land bridge that sits over the interstate. Tra c can ow below and the upper platform is reclaimed land that can be used in a variety of ways, from parks and playgrounds to business and residential space. Cooper’s transit proposal makes space for an eight-acre cap that “could create new a ordable o ce or retail space, supply shared parking, or support a ordable housing for parcels made undevelopable because they were narrowed by the construction of the highway.” e Metro Council is expected to take up the broader package late this year or in early 2021.

Molette says land investments by corporations — as long as they o ered landowners fair prices — could also be bene cial. He cites development in Kansas City as a good example of what’s possible.

“On Vine Street, where they have the [Negro Leagues Baseball Museum], Sprint moved viable o ce space there,” Molette says. “And the city had o ce space on that street, which meant [workers] went to lunch there. All those types of things help drive business [...] I think Nashville’s dropped the ball on a few opportunities like that.”

But even with the city’s newly sparked interest in supporting the North Nashville community — and Cooper’s hope for a Je erson Street cap — Molette doesn’t expect much will change. At least not soon. He has seen too many ideas and plans come and go and too many politicians focus on “ xing” problems that don’t exist. (A 0.35-acre park is nice but it doesn’t make a dent in the damage caused by decades of neglect.)

So what would be a good rst step so this newly ignited ame of support doesn’t go to waste? Molette wants people to listen, for one, and for investors to see the neighborhood as a viable investment option as opposed to a quick cash grab.

“Investment dollars have to be made available, but through the community,” Molette says. “Instead of just say, giving it to a developer to come in and make a decision, I think

Mayor John Cooper’s large transit investment plan includes as options several stretches of highway caps in North Nashville. Here are the visions for caps north of Je erson Street at D.B. Todd Boulevard and where Je erson crosses over the northwestern part of the downtown interstate loop.

it really needs to funnel through the community, whether it’s JUMP (Je erson Street United Merchants Partnership), New Level Community Development Corporation, Equity Alliance, Gideon’s Army — I think all those organizations have to be at the table.”

Rasheedat Fetuga, founder of Gideon’s Army, believes the highway cap included in Cooper’s transit plan is presented with good intentions, but she’s skeptical that it would ultimately bene t people who’ve lived in North Nashville for years, even generations.

Fetuga says what North Nashvillians need is nancial support, speci cally, to be repaid for the land and businesses they lost decades ago.

“Nashville should pay reparations, a universal living wage, something to indigenous people of North Nashville because there were over 150 businesses that had to close, people had to relocate,” she says. “It’s not enough for people who come in and gentrify the community to pop up and buy a cup of co ee to support these businesses. e city has to make a commitment to repay what was taken from these people. en we’ll know how serious Nashville leadership is about North Nashville.”