19 minute read

Favourite First Time Watches of '22

14. A Man Escaped (Robert Bresson, 1956)

Ever since 2019, I have been wanting to seek out this title when Peter Bradshaw compared The Irishman's treatment of the assassination of Jimmy Hoffa as Bressonian in construction. Having now witnessed Bresson's work in the flesh, I can understand the comparison in the slow and factual delivery but believe Scorsese was perhaps just as influenced if not more so by another film on this list, Mafioso. Bresson's influence can be more seen in Scorsese's friend Paul Schrader's works. Take nothing away from A Man Escaped though, this is a masterpiece that could be argued creates a new form of cinema. Each part of the escape is detailed so technically and specifically taking precedence over character development. Look at the title, it's all there to begin with. Up there with The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford for most revealing titles. There is something to be said though about the psychedelic effect of the way Bresson reveals information to his audience. You'll hear it in voice over narration, you'll then be told it in visual narration both through reported details in diaries and action. Put together, these have a strange impact as you're told the information in multiple forms and then with a carefully placed edit can come to question the reliability of this and there's an added suspense or uncertainty. According to Schrader, this is the exact moment Bresson's film achieve a state of transcendence. Notably, this is through the style rather than in substance. My admiration of this movie lies in it being a study of perspective. We never see outside the protagonists field of vision. We know nothing he doesn't. So don't expect any wide shots of the prison. Anything new to him as he escapes is new to us. No score either, it uses sound design as soundtrack to build suspense. A move, which definitely inspired Escape from Alcatraz . At first, you could accuse it of being too technical as a consequence of being meticulous but somehow in its intensity and its lack of cuts to different character perspectives becomes terrifyingly personal and indistinguishably human. In spite of the title, will French Ian Curtis really escape the prison? Why don't you go fucking find out for yourself.

Advertisement

13. Mafioso (Alberto Lattuada, 1962)

This film belongs to an area of cinema I have a lot of time for, the existential crime film. Surely, David Chase has seen this one? The Sopranos creator must have in order to carve those dreamy set pieces his characters lose themselves in. Unfortunately, this still remains widely unseen. A huge influence on Italian American directors and writers who acknowledge it but for some reason largely ignored by wider critics. About time we all went back to the source. Although, this came out back in the '60s, it remains shockingly fresh and hard to beat. Upon release, it received mixed reviews with many crediting the tonal shifts being a source of confusion. Ultimately, it is these tonal shifts that are the films greatest weapon. For 105 minutes, Lattuada is straight up fucking with you. What begins in your mind as, "Hahaha Italians" soon transforms in to "Jesus Christ Italians". During the initial scenes, you'll be shaking your head laughing half thinking Lattuada is having me on. A factory worker living in Milan returns to his native Sicily to see the family and the interactions are so exaggerated they adhere to just about every Italian stereotype you've ever held. They are presented as unfathomably overemotional and excitable with the hugging and kissing. Is this overacting for the camera? No, they're simply Italian. All this is part of Lattuada's joke, which becomes sicker by the minute. After all the nostalgic revisiting of his past, our protagonist soon has a run in with the local mafia. After another case of hugging and kissing, these mafia men then remind him he owes them a deed. Naturally, he is obligated to carry out a hit for them in America. Now, this is where the influence on Scorsese and Chase can be visible. Our central character is thrown about with no individual control by outside forces country to country to complete this mission he doesn't want to. One minute he's shoved in a box, then when the darkness subsides, he is in another place in another time against his will causing this to become existential. The murder is an act he must carry out with no understanding of its meaning and in the name of a powerful force he has no control over. These scenes are so surreal, they could well be one of Tony Soprano's troubling dreams. Scorsese does something similar in The Irishman by manipulating the time and space. Mafioso's third act is a rare cinematic thrill you cannot pass on.

12. Carlos (Olivier Assayas, 2010)

If like myself, you are hooked on good old American action, a project like Carlos is one to be welcomed with open arms. Too often action afficionados, whilst admiring set pieces, have to accept xenophobic and imperialist attitudes as a norm. Only way round them is to laugh it off as part of the silly package and view them as exposing the true nature of the American government. Ironic worship is key to handling them. Well, Assayas is here to say we don't need to have such right wing heroes. Finally, we can forget the John Wayne's and have a true left wing hero in Carlos the Jackal. Maybe you liked Che and Mesrine? Well, in frontman Edgar Ramirez the revolution has real sex appeal. Honestly, it has never looked so sexy. Witness as he hangs dong in one scene and then blows up a building in the next. All while New Order's Dreams Never End is pumping out in the background connecting the two scenes. Assayas fits comfortably in this modern serialised storytelling which nods to Feuillade's Les Vampires and Fantomas. Maybe even some of Fritz Lang's Spies in there. These all go right back to the 1920s but Assayas uses them to subvert the now popular Miniseries format and adds in some real style through all the post-punk songs. Expect Wire, The Feelies and The Lightning Seeds to score our Venezuelan revolutionary as he bounces round in the struggle for liberation. Never has a 300 minute plus film gone by so quickly. Believe there's 3 different versions of Carlos, a 165 minute film, a three part 319 minuter and an even longer 338 extended version. Not too sure which I did (watched it on Criterion Channel) but it definitely was not the 165 minutes. Over the stretched running time, you get to see this communists best work such as The OPEC siege in '75 and his later attempts to build an international terrorist organisation. Much respect. Much love. He's a version of James Bond we've never before. Assayas delivers b movie thrills but also manages to combine the espionage with global capitalism. Does it get any better than that? Also can we show some more love to The Wasp Network? Given the changing formats that have transpired in the streaming age, Assayas's knowledge of serials and how to modernise them makes the future of cinema very much in his hands.

11. The Virgin Spring (Ingmar Bergman, 1960)

Nothing reveals a cinephiles sensibilities quite like when The Virgin Spring is brought in to conversation. The tiring debate over whether Wes Craven's quasi remake

The Last House on the Left is art wages on. However, the reason we may never see a ceasefire here is because it ties in to an even wider and near unanswerable question of what art is. These two films are often used a short hand means of solving the argument. Put simply, The Virgin Spring is art and The Last House on the Left is not. To this day, people are still spinning this shit, it's incredible. Have you considered they are both art? Different types perhaps with one being more high art oriented and the other low art inclined. But both in their own ways, art. The story is nearabout the same with a bunch of bandits raping and killing a lone woman out running errands. The bandits then make the mistake of stopping off at the daughters house. Upon realisation of housing murderers, the parents contemplate revenge. Virgin Spring views such acts in response to religion. Bergman Challenges 60s taboos by weighing up the potential eternal damnation as a consequence of abandonment from God's code with the personal need for vengeance. Craven perfectly updates the formula to tie in to the violent nature of Vietnam depicted on television and a commentary on the nasty exploitation films that followed on from Blood Feast. His film operates so close to the line of acceptability that it causes people to wonder whether it critiques, exposes or flat out endorses violence. Craven's supporters will often point out the themes in both films are exactly the same and they will address the stupidity of people's beliefs in that just because Ingmar Bergman does something it's automatically art. Understand, none of this is new discourse and the annoying part is that this endless sparring stops us from realising that both films are art and although very similar do have differences due to the times they were released. In particular, I had no idea that Virgin Spring is Rashomon inspired with the way the rape is presented and the manner in which the father has to trust the information given to him. Maybe it's time we packed in this silly dispute over which is art and focused on what each reveals about their time periods and stylistic choices.

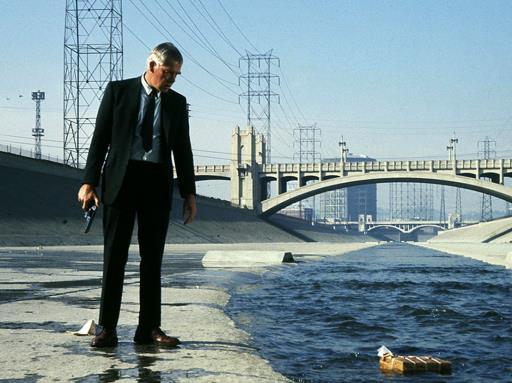

10. Point Blank (John Boorman, 1967)

Everyone knows the story, in 1959, the French took 3 films to Cannes that forever changed the course of cinema. Such a reflexive post-modern style becomes known as the French New Wave. Directors like Godard, Truffaut and Varda dominate the '60s. After spending half the decade losing the battle to European arthouse cinema, the now old fashioned Hollywood, facing its own extinction, decides to fight back and employ some of these new tricks. This kickstarts the greatest of all cinematic movements: New Hollywood. Boorman's Point Blank is credited as the brave film to first incorporate the new techniques pioneered by the French. The result is another existential crime flick, which would catch Scorsese's attention and pay homage to in Mean Streets. The French would parody American noirs and with this in mind, Lee Marvin came up with the idea of adapting Richard Stark's Hard Boiled fiction Parker series. Except, this goes well beyond adaption of pulpy detective and into artful subversion. It keeps the books non-linear structure but expands on it to create a stream of consciousness narrative. Boorman would prove to be a master of trippy on Excalibur and The Exorcist 2 (thoroughly underrated) but Point Blank is a league of its own employing a Gaspar Noe like death dream structure. Re-examines the very nature of a crime film and achieves a direction which comes off as a combination of Hitchcock's Vertigo and Mann's Thief. In a sense, that also makes it very Taxi Driver too as it borders in to fantasy. Weirdly, Tarantino opposes the film and believes that after the glorious opening 10 minutes descends in to a generic TV Cop show. He could not be more wrong. He mistakes this with the Mel Gibson adaptation Payback, which Boorman described as so bad it could be the script he threw out a window making this one. Instead, Tarantino champions the 70s crime film The Outfit as being better as it comes closer to what Stark was intending. As much as I enjoy both Payback and The Outfit, they don't transcend the source material like Point Blank does. You'd think of all people, a post-modern director like Tarantino would understand what Point Blank was doing, right?

9. Coming Home (Hal Ashby, 1978)

Never in a million years did I ever think I would encounter again in my life a set piece as good as the ones in Goodfellas and Boogie Nights. They're the top tier. The measure. Over the years, just about everyone has had a go at intense montages to rock and pop soundtracks. As has been revealed, merely sticking a banging track over these montages doesn't elevate it into excellence. No, it takes something more in the assembly of the sequence and that's what separates the men from the boys. We can add Hal Ashby to the list of masters of intercutting action. Towards the middle, he teases us with a skilled sequence soundtracked with The Rolling Stones Sympathy for The Devil. However, this is nothing in comparison with the climactic set piece in which there is a race against time. War veteran Bruce Dern returns from battle an angry alcoholic and after hearing the news of his wife's infidelities, goes after his rifle ready to go catch him a couple of bodies. His hit list? Jon Voight and Jane Fonda (the best actress of all time bar none, fuck your Meryl Streeps). Right remember in Casino when DeNiro hears his wife's tied his kid to the bed? Yeah, so he goes home, unties the kid, goes to Def Con 1 and calls Mr Potato Head to bring over the shotgun ready for war. Throughout all of this, Devo's Satisfaction is booming. Scorsese uses Mark Motherbsbaugh's excruciating "b-b-b-b-baby" bit to put the tension through the roof. Ashby possibly inspired this move with his use of The Chambers Brothers's Time Has Come Today. About 3 minutes in to the song breaks itself down to its most minimal elements then slowly builds back up again at which point the singer screams, "Oooooooooooooooooh!". All this is timed perfectly with the action to create something so exhilarating and to a standard I thought I'd never see again. Of course, I couldn't help go back and watch all Ashby's other incredible movies. He's no stranger to critical acclaim but his catalogue could do with some more attention. So if you like this or Harold and Maude or The Last Detail or Shampoo, tell a friend. Spread the word.

8. Crazy Thunder Road (Gakuryu Ishii, 1980)

I have said all I wish to say about this punk masterpiece in the meantime back in Issue #6. Not enough time has passed to add anything more to the table.

7. Shin Godzilla (Hideaki Anno, 2016)

Oh, this is without a doubt, the most Jacob Kelly movie I've seen all year. So much so, I watched it twice and will continue to do so again and again. There's just no stopping me. When this released, back in 2016, a respectable acquaintance known as The Goshima invited me round to get on the edibles and watch this. Since, I hadn't followed the series too closely, I felt the need to decline such an invitation. Turns out this is a reboot as well, it's fifth one to be precise. So I could have easily seen it without even the slightest confusion. Never have I regretted anything more. If you only ever seen the original/Roland Emmerich's/Gareth Edwards's versions or even if you've never seen a Godzilla movie, Shin Godzilla is the best place to start. This fucking kaiju's won Guinness world records for his service and length of time in the field. This is his 31st outing making him the longest running franchise. I've seen probably about half of his adventures and I have to say this is the first to really rival the original. The Master of disaster Emmerich's American remake failed to capture the spirit of the series and was never really seen as a threat with critics calling it GINO (Godzilla In Name Only). On the other hand, Edwards's version took the creature in to the Kubrickian realm earning great appreciation. Toho, the studio who started it all, had to return and take their creature back from the dirty yanks(who caused him to exist in the first place with their dirty tricks in Hiroshima) and so hired Neon Genesis Evangelion's creator Hideaki Anno. This led to the quite frankly flawless Shin Godzilla. Ok, so what makes this the ultimate Godzilla ideal for any newbies? A mix of both practical and digital effects. There's this great joke in that the first appearance of Godzilla he looks completely pathetic and outdated. Over the course of the movie, he keeps evolving into stronger forms allowing them to reference the history of the series, nostalgically recreating designs appropriate to each era until finally we can see the latest technology in his full form (which is agreed to be the scariest Godzilla has ever looked). Musically, it uses both old and new too. We have Akira Ifukube's original theme, the banger sampled by Pharoah Monch on Simon Says and then this new updated rock and electronic score from Shiro Sagisu. Usually with Godzilla, far too much time is spent on the scenes involving the monsters attacks and not enough on the humans planning to stop him (which can be equally funny). Shin Godzilla is the best written since the original. If Edwards's take borrowed from 2001, Anno's looks to Dr Strangelove turning this in to a political satire as much as it is a Kaiju. More recent disasters such Fukushima and Tohoku are drawn upon for inspiration and the useless manner in which these are dealt with by politicians is critiqued. It could well be the best attack on bureaucratic red tape ever undertaken in cinema. Anno is the only director who is as interested in the military meetings as he is the fighting. Can't say I've seen anything quite like his scenes where the politicians and generals meet up to discuss tactics. He has these left, right pans and constant moving camera. There's a flair and immediacy that should have been here all along. He doesn't switch off at all. You're never left chanting, as I often do a few beers in to these movies and dissatisfied by all the human scenes, "We want Godzilla! We want Godzilla". Those wanting the simple dumb shit, should stay tuned for when Godzilla's Lazer beam comes out. A monumental moment in cinema. Apparently, when this came out, the Japanese were raving about it and gave it 7 Japanese Academy Prize awards including best picture and director. Whereas, the western critics were less enthused. Honestly, if I'd have been at the western premiere and not heard critics on their feet cheering, it wouldn't have gone down like that, I'd have started screaming, "Boooooo, you fucking bores!" and beat the living shit out of every other critic in the room. Nothing but respect for the king of the monsters.

6. Until the End of the World (Wim Wenders, 1991)

He's the undisputed king of the road movie and this might just be his 2001. In 287 minutes Wenders takes you right around the world. Make sure you catch this version as the 158 minute cut is merely a theatrical contractual obligation. You will not get the same experience from it and Wenders describes it as a "reader's digest" at best. This is a hard film to write about because it's emotional scope is too great. Well, too great for this man at least. Resorting to pathetic personal emotional descriptions has never done anything for me and so I refuse to sink in to it. You want the experience, you're going to have to get it for yourself. The fact he puts in a shift like this and then dedicates it to his family is an absolute flex. Every adventure does need its soundtrack though and for this Wenders calls on all his post-punk pals who made their own music for the project. Talking Heads, Julee Cruise, Lou Reed, R.E.M, Elvis Costello, Patt Smith, U2, Peter Gabriel and Elvis Presley. There's a whole section in Australia so expect an appearance from David Gulpilil and a Nick Cave song. Even has the fucking Chubby Checker and as you bloody well know, I'm a Chubby Checker man. ROUND AND ROUND, UP AND DOWN WE GOOOOOOOO. Depeche Mode come out the strongest with Death's Door, which is my favourite scene. When it comes on after this 2 hour journey, you'll be cheering on the protagonist (William Hurt) and his partner (some extremely attractive French Kirsten Dunst) as they go to meet up with their parents. I said I'd stay away from the emotional side of this but this is a powerful moment. Yes, the cinematography is pretty and the music delicious but this isn't just a light trip around the world. Towards the end it begins to resemble a horror movie, observing the dangers of digital technology, which was starting to take off. In the film a device which can records dreams causes the characters to descend in to pure narcissism. They get lost in fantasy contrasting with the Malickian love of nature shown throughout the movie. Of course, I'd love for someone to take this concept and turn it in to an erotic thriller. I'm envisioning something like that sex scene in Demolition Man with characters getting lost in fucking in fantasy over reality. Oh did I mention, Sam Neil's in this and has a great scene where he kills it on the piano. From Sci-fi noir to travelogue to philosophical horror, this movie has it all.

5. The Vanishing (George Sluzier, 1988)

You know, this could well be the scariest movie ever. Stanley Kubrick certainly thought so because after he first saw it he called up Mr Sluzier to inform him that he'd shat his pants. Sluzier's response was something like "but sir, you are the director of The Shining and my film is only rated 12". To which Kubrick said, "The Shining is kids stuff compared to this". He would then go on to discuss editing. As I didn't want to give anything away on this my initial review was simply, "Nicolas RoEGG". A play on the British director who developed his own particular style of flash forward editing, most notably in Don't Look Now. So, when you watch this keep an eye out for eggs. Not easter eggs. Literal eggs. Let's just say, there's a lot. Rife in symbolism! I watched this movie three times in 2022 cause I couldn't get it out of my head. First time I saw it, I couldn't sleep so had to go on a walk round the block for a good hour. So how could a movie deemed appropriate for 12 year olds be so terrifying? Although not particularly graphic in violence, it gets you into the headspace of a serial killer. Even better so than Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer. In some ways, you'll almost be jealous that this killer is definitely unlocking more pathways mentally than you could ever dream of. As though he's on some Limitless type drug. What we have is a couple on holiday and the woman completely disappearing at a service station. The man doesn't forget the incident and becomes obsessed with the truth. Years later, the abductor makes contact and promises to tell him what really happened if he will get in his car. On the little boys road trip they have going, the psychopath reveals little incidents in his life where he came to realise his behaviour wasn't normal. The set pieces are so carefully chosen that you'll think surely only a mad person could have written them. Each time our psychopath steps outside of what is expected and in a sense arguably achieves true free will. That's what scares me about this film. It renders your own freedom as something of an illusion and your human behaviour predictable. Individuality something only a psychopath could succeed in. Whereas we would ask why would we do something, this guy asks why wouldn't we, going further than any of us. Takes you to the edge of faith and sanity. Villenueve stole so much from this for Prisoners, lifting direct shots and ideas. Sluzier even has a Hollywood remake of his own, which people say is an entirely different movie. You might think it's ridiculous calling this scary but by the time the credits roll. You'll know.

Something rare in cinema happens. Your beliefs will be challenged. Is there anything scarier than that?

4. The Train (John Frankenheimer, 1964)

It would be foolish to suggest that this isn't a critically acclaimed movie but somehow it deserves greater appreciation than it has. Frankenheimer's masterpiece deserves to be spoken about in the same breath as Seven Samurai, The Wild Bunch and The Good, The Bad and The Ugly. Frankenheimer has a great deal in common with Kurosawa to the point they feel cut from the same cloth with a similar ethos to filmmaking. Both fashion these epics which are a marriage of action and ideas. They keep their films moving but never run on empty. Look no further than Ronin, which weaved in samurai myths in to the American crime film. Comparing mercenary thieves to Ronin. Skilled veterans with questionable levels of honour roaming the country in search of temporary jobs to stay alive. Continents and time may separate them but fundamentally they are one and the same. That's your proof that Frankenheimer is a student of Kurosawa. These filmmakers are the kings of the genre: men on a mission. The Train is pure technical mastery too that echoes Fordian qualities with all the beautiful wide shots. Also, have the added benefit that it isn't cruel to the Native Americans. If you ask me, this wipes the floor with any of John Ford's contributions to cinema. On action alone, it trumps any of Stagecoach and Ford wishes he could have come anywhere near to having a message as powerful as The Train.

Frankenheimer's film may well go down as the greatest commentary ever on the significance of art. No time better to illustrate that than during war time. What we have is a bunch of Nazi's trying to move some stolen art across the country and American soldiers who have been sent to retrieve the cherished works. Those sent in to reclaim the goods begin to question the value of the mission when many of their lives are taken. Now that is action and ideas. The best kind of filmmaking there is and ever has been. Had Frankenheimer been given better projects like this, I truly believe he really could have emerged as America's greatest director.

3. Ugetsu (Kenji Mizoguchi, 1953)

Sadly, I left it far too long to finally get to watching Ugetsu. After a bad experience with Sansho the Bailiff , I'd been put off Mizoguchi, believing him to be overhyped rubbish and was not looking forward to going deeper in to his catalogue. Even with The 47 Ronin, he somehow managed to make that familiar story incredibly dull. Turns out avoiding his other offerings was a grave mistake. This marks a decade of real Japanese dominance and opened up the West to what the country had to offer cinematically. A highly reflexive film that critiques the countries uncomfortable relationship with militarism, which led to their involvement in World War II. Mizoguchi reaches inward to address his own participation through making the pro-war propaganda movie The 47 Ronin. Stylistically, it's a bizarre creation as it fuses elements of the Jidaigeki (their word for a period drama) with a ghost story (their common kind of horror film). You also have this strange mix of tragicomedy with a dude going through desperate lengths to be a samurai to the point of abandoning his own family alongside something as haunting as Kwaidan and Onibaba Yet to see Kuroneko but these all belong in the same ball park. Adding to the abandonment angle, Mizoguchi manages to craft a feminist narrative. Women in this story are left to fend for themselves and provide for the children. In the second half, we see the 'comfort women', a name given to those who turned to prostitution in the desperate times. In Mizoguchi's world, men are losers desperately seeking to be samurais and it’s the women who are the strongest.