Bourbon_Fall19_Ed-final.qxp_Road Trip_Cinci.qxd 8/28/19 5:13 PM Page 14

liquids | spirits

enaissance on BY SUSAN REIGLER

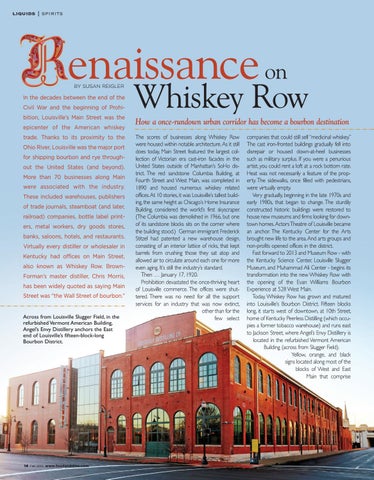

In the decades between the end of the Civil War and the beginning of Prohibition, Louisville’s Main Street was the epicenter of the American whiskey trade. Thanks to its proximity to the Ohio River, Louisville was the major port for shipping bourbon and rye throughout the United States (and beyond). More than 70 businesses along Main were associated with the industry. These included warehouses, publishers of trade journals, steamboat (and later, railroad) companies, bottle label printers, metal workers, dry goods stores, banks, saloons, hotels, and restaurants. Virtually every distiller or wholesaler in Kentucky had offices on Main Street, also known as Whiskey Row. BrownForman’s master distiller, Chris Morris, has been widely quoted as saying Main Street was “the Wall Street of bourbon.” Across from Louisville Slugger Field, in the refurbished Vermont American Building, Angel’s Envy Distillery anchors the East end of Louisville’s fifteen-block-long Bourbon District.

14 Fall 2019 www.foodanddine.com

Whiskey Row How a once-rundown urban corridor has become a bourbon destination The scores of businesses along Whiskey Row were housed within notable architecture. As it still does today, Main Street featured the largest collection of Victorian era cast-iron facades in the United States outside of Manhattan’s SoHo district. The red sandstone Columbia Building, at Fourth Street and West Main, was completed in 1890 and housed numerous whiskey related offices. At 10 stories, it was Louisville’s tallest building, the same height as Chicago’s Home Insurance Building, considered the world’s first skyscraper. (The Columbia was demolished in 1966, but one of its sandstone blocks sits on the corner where the building stood.) German immigrant Frederick Stitzel had patented a new warehouse design, consisting of an interior lattice of ricks, that kept barrels from crushing those they sat atop and allowed air to circulate around each one for more even aging. It’s still the industry’s standard. Then … January 17, 1920. Prohibition devastated the once-thriving heart of Louisville commerce. The offices were shuttered. There was no need for all the support services for an industry that was now extinct, other than for the few select

companies that could still sell “medicinal whiskey.” The cast iron-fronted buildings gradually fell into disrepair or housed down-at-heel businesses such as military surplus. If you were a penurious artist, you could rent a loft at a rock bottom rate. Heat was not necessarily a feature of the property. The sidewalks, once filled with pedestrians, were virtually empty. Very gradually, beginning in the late 1970s and early 1980s, that began to change. The sturdily constructed historic buildings were restored to house new museums and firms looking for downtown homes. Actors Theatre of Louisville became an anchor. The Kentucky Center for the Arts brought new life to the area. And arts groups and non-profits opened offices in the district. Fast forward to 2013 and Museum Row - with the Kentucky Science Center, Louisville Slugger Museum, and Muhammad Ali Center - begins its transformation into the new Whiskey Row with the opening of the Evan Williams Bourbon Experience at 528 West Main. Today, Whiskey Row has grown and matured into Louisville’s Bourbon District. Fifteen blocks long, it starts west of downtown, at 10th Street, home of Kentucky Peerless Distilling (which occupies a former tobacco warehouse) and runs east to Jackson Street, where Angel’s Envy Distillery is located in the refurbished Vermont American Building (across from Slugger Field). Yellow, orange, and black signs located along most of the blocks of West and East Main that comprise