FLUX

Issue 25 | Spring 2018

Issue 25 | Spring 2018

Challenging gender identities and roles

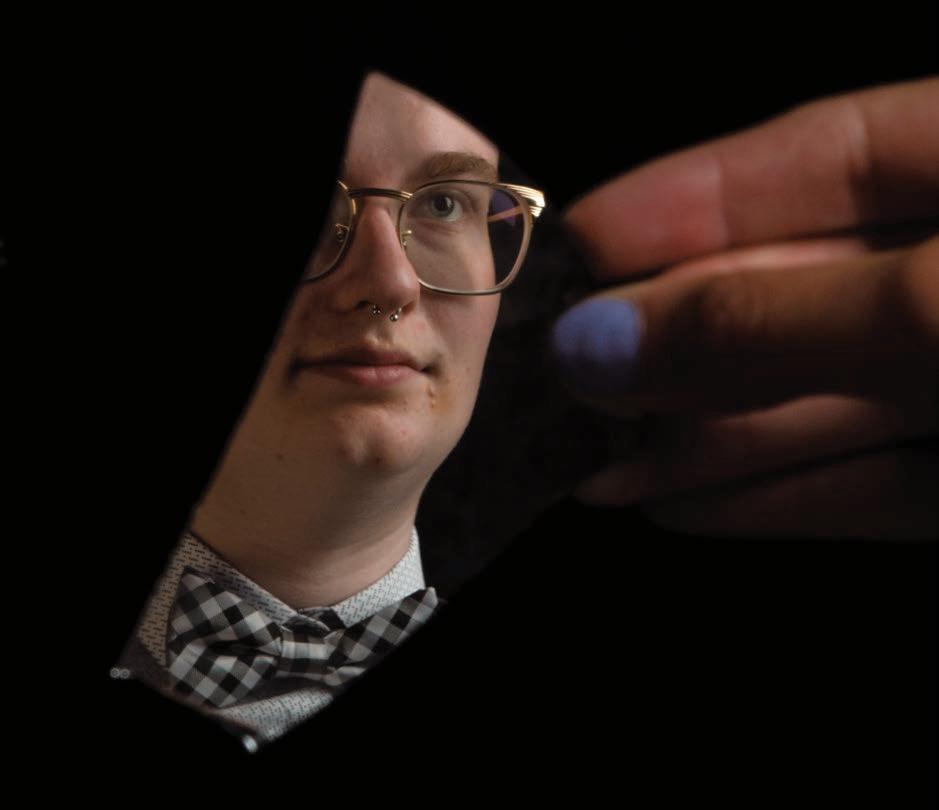

Avi Yocheved, age 19, is a self-identified genderqueer freshman at UO. They’re featured in the cover story about gender identity beyond the male-female binary. Throughout this issue, we feature reflections on gender throughout life and people challenging traditional gender roles. You can find even more stories, including a video and podcast episodes, on www.fluxstories.com

ur magazine’s name means continuous, flowing change. Flux is dedicated to telling stories that reveal this change. If there’s one constant in our lives, it’s that they’re in flux. This year, something we all see changing is our ideas around gender, and specifically, masculinity, in America. Despite a disheartening climate in political leadership for gender equality, we’ve heard women of all backgrounds find a voice through #metoo and the Women’s March. We’ve seen some men who abused power have it taken away, and others reconsider their approach to women and what kind of man they want to be. Others still are reaffirming a commitment to gender equity and looking beyond equal to see how they can raise women and non-binary people up to be leaders.

Flux took a close look at how gender plays out on our campus and greater Willamette Valley communities. Each student sought out stories of how gender affects our neighbors’ and peers’ lives. We asked what they’re doing to be stronger and more humble in their identities. We asked how they’re expanding their communities to be more inclusive. We asked what it’s like dealing with judgment, either for their choices or for things they had no choice in, and what it’s like when gender isn’t a factor. We collected a broad range of experiences here in this magazine, and yet there are so many more stories to be told in the spectrum of gender.

Beyond the stories, we tabled on campus and asked people for words they associate with men, women and non-gendered people and hosted a conversation, asking, “What makes a good man?” Through these projects, we challenged the idea of gender as a binary and masculinity as a dominant force in our society. What we heard is that men don’t want to be forced into an either/or with their identity. That they increasingly recognize their privilege and want to use it to help those in need of a voice. We learned that a shift in what our society rewards—a shift away from competition and aggression— may alleviate the conflict among us and make more room for positive action.

We learned that whether it’s in pinball arcades, yoga studios, science class, scouting troops, hospitals, fraternities, monasteries, on mountain bike trails or more indirectly throughout life, our bias and expectations influence our experience of gender in subtle and powerful ways. Yet despite this, we found people challenging tradition, defying gender roles, and breaking free of the limitations put on them by society.

Though we tell stories of change, there’s so much further to go before we reach gender equality. Our purpose here is to comfort the afflicted and afflict the comfortable. We hope this issue is soul food for those hungry for change, and inspiration for those who might not think we need it.

Anna Glavash Editor in Chief

EDITOR IN CHIEF

Anna Glavash

ASSOCIATE EDITOR

Braedon Kwiecien

COPY EDITORS

Emily Loudermilk

Cassidy Haffner

Mara Welty

WRITERS

Samuel Bass

Desiree Bergstrom

Taylor Brown

Aubrey Bulkeley

Edward Burnette

Kenzie Farrington

Emily Loudermilk

Ryan Nguyen

EDITORIAL ADVISOR

Todd Milbourn

PHOTO

PHOTO EDITOR

Dana Sparks

PHOTOGRAPHERS

Ben Bilotti

Hannah Neill

Miranda Daviduk

PHOTO ADVISOR

Sung Park

ENGAGEMENT EDITOR

Ashley Rendall

SOCIAL MEDIA COORDINATOR

Dana Norder

VIDEO EDITOR

Miranda Daviduk

VIDEOGRAPHER

Owen Schatz

PODCAST HOST

Braedon Kwiecien

PODCAST PRODUCERS

Vinh Bui

Aubrey Bulkeley

ART DIRECTOR

Emily Harris

ASSISTANT ART DIRECTOR

Sierra Pedro

DESIGNERS

Cheyenne Polen

Mariel Cathcart

Devon Reed

Ryan Hsu

Sophia Kim

Maile Sur

ILLUSTRATORS

Mariel Cathcart

Erick Wonderly

DESIGN ADVISOR

Steven Asbury

REPRESENTATION MATTERS

A look at gender representation at UO

HOW DO YOU IDENTIFY? A self-assessment of gender and sexual identity

EDITOR’S LETTER

BEATING THE MACHINE Eugene’s all-women competitive pinball league

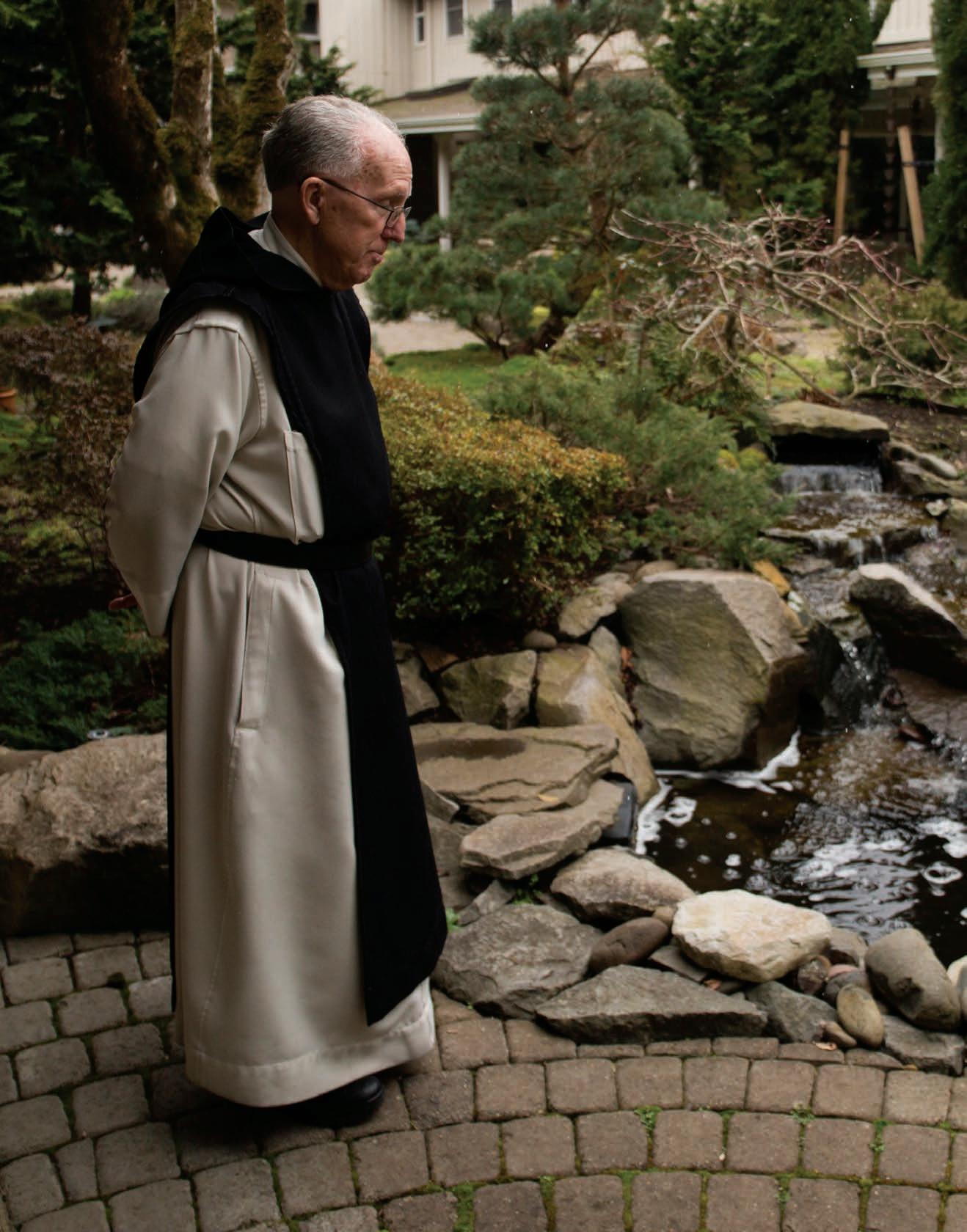

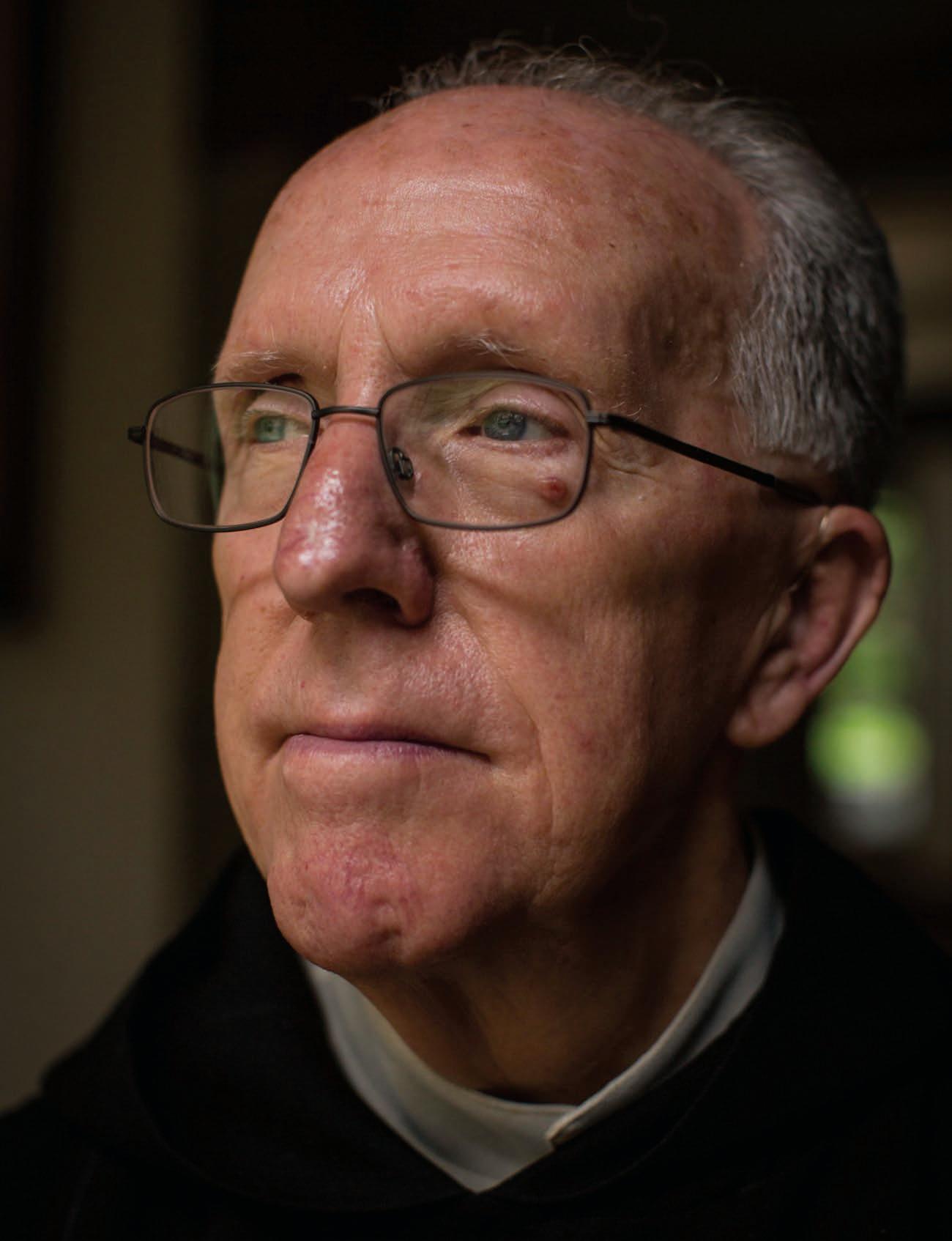

CLOSER TO THE SPIRIT Trappist monks finding community and contemplation

WHAT MAKES A GOOD MAN?

Musings on a world where masculinity is unfettered

BROKEN GLASS

A timeline of women in media

BLAZING A TRAIL

Scouting groups forge a more inclusive path

MEN ON THE MAT

Making yoga more accessible

BALANCING THE EQUATION

UO students empower girls in STEM fields

A NEW CHAPTER

UO fraternities make inclusivity the norm

CHILDFREE AND HAPPY Eugene group normalizes kid-free adulthood

BREAKING THE BINARY One UO student healing from gender-related trauma

In an April speech, University of Oregon President Michael Schill highlighted the school’s commitment to diversity, saying, “The University of Oregon has a profound duty and mission to promote and celebrate diversity of all types.” Yet when it comes to gender diversity on its faculty, the scale remains tipped in favor of men. Data shows that female tenure-related faculty increased by 4 percentage points in 2016. While that’s up from 35 percent in 2005, statistics reviewed by Flux show that UO has work to do before reaching gender parity across campus.

Number of tenured female faculty in the physics department:

Number of tenured male faculty in the physics department: 21 1

Number of female presidents in UO history: zero 23 33

Percent of total tenured faculty in 2016 who are women:

Percent of tenured faculty who are women in the five highest paying departments on average in the College of Arts and Sciences: 44

Number of tenured female faculty in the math department:

Percent of deans of UO colleges who are women:

% % %

Number of tenured female faculty in the computer and information science department:

Percent of heads of departments or program directors in College of Arts and Sciences who are women: 23

Number of tenured female faculty in the economics department: 3

Number of tenured male faculty in the computer and information science department: 10 0 37

Number of tenured male faculty in the economics department: 11 2

Number of tenured male faculty in the math department:

Data obtained from the University of Oregon Office of Public Records

Before we ask others this question, we should know our own answer. Here’s a way to assess the full spectrum of your identity beyond either/or. Place a mark on the line to indicate where you exist. Remember, you are not defined by your sex assigned at birth.

Check the box of what you identify with most.

Queer:

Identifying outside of heterosexuality or the male-female gender binary. This word has been reclaimed from its use as a slur, so it’s typically a personal choice to use it.

Sex Assigned at Birth

A classification based on anatomy and genetics.

Cisgender:

Identifying as sex assigned at birth.

Transgender:

An umbrella term for those identifying differently from the sex they were assigned at birth.

Man/Boy

Female

Male Other/intersex

GENDER IDENTITY

Your internal sense of self. Who you are on the inside.

Nonbinary

GENDER EXPRESSION

Masculine

Woman/Girl

How you present yourself externally. What the world sees.

Androgynous/Agender

PHYSICAL ATTRACTION

Non-binary:

Identifying as not conforming to the gender binary of male and female.

Androgynous:

Presenting with qualities of both male and female expression.

Feminine

Your sexual orientation. Who you want to do sexy things with.

Women Men

Men

Asexual/Bisexual/Pansexual

ROMANTIC ATTRACTION

Your heart’s desire. Who you are emotionally drawn to.

Women Panromantic/Biromantic/Aromantic

Presenting with gender-neutral expression.

Asexual:

Agender: Not sexually attracted to anyone.

Bisexual:

Sexually attracted to both men and women.

Pansexual: Not romantically attracted to anyone.

Sexually attracted to all genders, including non-binary.

Aromantic: Romantically attracted to both men and women.

Biromantic:

Panromantic:

Romantically attracted to everyone.

On April 13th, Flux hosted a community discussion around the question, “What makes a good man?” With our guests, we talked about our role models of any gender and what we admired about men in our lives. Then we asked, “What gets in the way?” and talked about some barriers men face. We ended with the question, “If nothing got in the way of being a good man, what would the world look like?” Here’s some of what we heard.

Better spaces of

Every individual will claim their own

A place full of more

broad spectrum Like a

accepted

It would look like a more

Women in the media have been fighting to break the glass ceiling since long before 1955, but the last 63 years have seen unprecedented leaps toward equality. These women’s struggles, achievements and resilience have led to the present, where women are closer than ever to fair treatment in the industry.

On February 23rd, women are allowed into the balcony above the ballroom of the National Press Club (NPC) in Washington D.C., to cover big speeches by well-known public figures, after pressure from the Women’s NPC, who had no prior access to such events

Nan Robertson moves to the NYT Washington Bureau. Throughout her career Robertson is forced to cover important speeches from the crowded balcony of the NPC. She later writes a book about her experiences titled “The Girls in the Balcony”

On March 16th, 46 women on Newsweek’s staff sue the magazine for gender discrimination and become the first women of media to file a lawsuit. The same day, Newsweek publishes a cover piece on the Women’s Liberation Movement titled “Women in Revolt ”

In 1955, Nan Robertson is hired to the NYT as a writer in their women’s section. In 1959 she joins the Metropolitan section

In September, the NYT hires Nancy Hicks Maynard, who is later promoted to become the first black woman reporter at the paper.

As of 1970, only 25 percent of the Newsweek masthead is made up of women, and most of those women are researchers, not reporters or writers

On January 15th, the National Press Club votes to admit women as members and later that year, on March 3rd, 24 women become the first female members of the club.

Nan Robertson receives a Pulitzer Prize in journalism for feature writing, making her the third woman from the NYT to ever receive the prize. Robertson is the 51st Pulitzer winner for the newspaper

Newsweek’s masthead is 39 percent women.

Multiple women accuse prominent men in media of sexual harassment and assault. The accused includes film producer Harvey Weinstein and Amazon Studios president Roy Price

On November 7th, six women from the NYT file a class-action lawsuit against the paper for gender discrimination, claiming to represent 564 women employed by the company.

Isabel Wilkerson, while working as the Chicago Bureau Chief of the New York Times, becomes the first black woman to ever receive a Pulitzer Prize for feature writing.

On October 15th, 2017 Actress Alyssa Milano tweets to her followers to reply “Me too” if they had ever been the victim of sexual assault or harassment, prompting the social media beginning of what becomes known as the Me Too movement along with the hashtag “#metoo”.

The Time’s Up movement is founded on January 1st by women in the entertainment industry. A movement slogan reads, “The clock has run out on sexual assault, harassment and inequality in the workplace. It’s time to do something about it.”

Tarana Burke, a sexual assault victim, coins the phrase “Me too”, and creates a MySpace page. Her intention is to help and connect women of color who, like herself, have survived sexual violence

On March 18th, Jessica Bennett and Jesse Ellison, while working for Newsweek, revisit the story of the 1970s lawsuit in a piece titled Young Women, Newsweek and Sexism. They note that men had written all but six of the magazine’s 49 covers from the previous year. Their article questions how much has actually changed.

In late 2017, several more prominent men in media are accused of sexual harassment, assault and misconduct, including Today Show co-host Matt Lauer and Charlie Rose of CBS, who were both fired after the allegations surfaced

On Monday, April 16th, 2018 The New York Times, led by Jodi Kantor and Megan Twohey, receives the Pulitzer Prize in Public Service for “spurring a worldwide reckoning about sexual abuse of women.”

Following the day’s lesson in orienteering at Mount Tabor Park in Portland, Timberwolf troop leader Alan Fryer congratulates Aida Foltz on earning a new merit badge for wilderness first aid. Between them lies the troop’s mascot, a stuffed timberwolf.

Scoutmaster Ethan Jewett woke up late in his tent. It was 2013, and the first day of a camping trip he was leading. He poked his head out of the tent and saw three of his younger scouts in a firebuilding competition.

The morning was a rainy, northwest start to a day. The damp wood the scouts were using required them to follow a strict process to successfully build their fire.

As Jewett looked on, it quickly became clear that only one of the fires would ignite. The two boys floundering in their attempts to conjure flames chose to abandon their fires and pushed their extra kindling into the winner’s fire. The fire grew larger in front of the victorious girl, and her two troopmates congratulated her.

“I think that it’s absolutely magical to have an opportunity at that early age for boys to see the true capability and caliber of their female counterparts,” said Jewett.

Jewett leads the 55th Cascadia troop of the Baden-Powell Service Association (BPSA) in Portland, which was founded in 2013. It’s one of a growing number of scouting troops in

Oregon and across the country that are taking a more inclusive view of gender. Driven by social change, demand from parents and political pressure, even traditional scouting organizations such as the Boy Scouts of America (BSA) are finding ways for boys and girls to work together.

In October 2017, the BSA announced it would begin allowing girls into it youngest age groups of scouts, commonly known as Cub Scout dens. However, these dens would still be segregated by gender, only allowing girls to attain leadership positions over other girls, albeit now as part of the BSA. In May, the organization announced it will drop “Boy” from the name of the program for older scouts, which will be known as the Scouts BSA starting in February 2019. At that time, girls will be allowed in and eligible for the prestigious Eagle Scout rank.

“This is one of those cases where the United States is late to the party,” said Jewett. There is very little sex segregation in scouts in other countries. The exceptions to this are Bahrain, Kuwait, Pakistan, Papua New Guinea and Yemen, among others.

Jewett, who’s also a provost commissioner of the Western Region of the BPSA, said the growing number of inclusive programs are

helping kids to develop empathy and other skills. “It’s important for girls to experience that equality and that mastery alongside boys. It’s just there for everyone to see and, quite frankly, it makes the boys bring their A-game,” he said.

The Baden-Powell Service Association began in 2006 and bases its ideology on traditional scouting. According to the organization’s website, this entails “good citizenship, self-reliance, loyalty and outdoor skills” in addition to “empowering youth through hands-on practice” as laid out by Boy Scouts founder Robert Baden-Powell in 1907. Though modeled after the Boy Scouts, the organization has always allowed girls and members of the LGBTQ community into its ranks and introduced the Rover Scout program for people over the age of 18. The environment fostered by the BPSA creates dynamics of equality and diversity early in childhood and provides an alternative to the setting traditionally offered by the Boy Scouts of America.

Jewett grew up in California and was a member of the BSA troop in his hometown.

“Looking back, it’s easy to see there were parts of me that were heavily influenced by the scouts,” said Jewett. He was a patrol leader and, among other activities, went on backpacking missions, long hikes and trips to San Francisco.

By the time Jewett’s son Travis was old enough to participate in a scouting troop, Jewett did not consider the BSA. “When my son turned five in the fall of 2012, I was definitely bummed with the Boy Scouts of

America,” Jewett said. Though neither he nor his son is homosexual, Jewett wanted an allinclusive environment for his son. At the time, the Boy Scouts of America was still a full year away from allowing gay scouts to join and two years from allowing gay scouting leaders.

Despite all the changes BSA has made since 2012, it wasn’t the right fit for Jewett then, so he opted for an alternative. He and a couple other dads began taking their children hiking and camping in lieu of joining an actual scouting program.

Soon after, he says his wife brought to his attention an article about a charter group of the BPSA. “Within a day or two, Travis and I got on the BPSA website, broke out a credit card and filed a charter for our group in north Portland,” Jewett said.

As the march towards equality, specifically regarding same-sex marriage, picked up speed in recent years, the Boy Scouts of America was faced with the growing problem of not allowing girls or members of the LGBTQ community to join.

These issues were epitomized by the case of Geoffrey McGrath. He joined the Boy Scouts in central California when he was 7 years old and earned the status of Eagle Scout just before turning 18. He went on to become a junior assistant scoutmaster, taking kids to scout camp until he was 20. But a year later his relationship with the Scouts changed.

“I came out when I was 21 to the local scout troop,” said McGrath. “I said I’d obviously still be happy to take the kids to camp, but my status had changed and I thought they should be aware of that. At which point, they

After completing the day’s navigation challenge at Mount Tabor Park in Portland, Wyatt Poe, left, and Henry Pilcher joke around while waiting for the meeting’s closing ceremony to begin.

After completing the day’s navigation challenge at Mount Tabor Park in Portland, Wyatt Poe, left, and Henry Pilcher joke around while waiting for the meeting’s closing ceremony to begin.

just disinvited me from further involvement.” McGrath, 53 now, spent over 20 years uninvolved with the Boy Scouts of America. During that time, he earned a master’s degree in social work and began working as a countywide crisis manager for at-risk youth and those suffering from mental health problems in Seattle.

Four years ago, McGrath began working with the BSA again. He started a new scout group, Troop 98, in a neighborhood outside of Seattle. A majority of the kids that McGrath works with in his area are innercity youth who rarely have access to the kinds of activities and opportunities presented in scouting programs. “A lot of the kids had never been to the woods before, have no swimming skills, have never canoed and done things like that. We were able to bring those kinds of experiences to them,” said McGrath.

He said the troop would not only bring scouting to inner-city youth but would also welcome all boys regardless of sexual orientation or identity. “When we started the troop, it was known by all parties that it would be inclusive, at least for boys, when it came to

LGBTQ issues,” said McGrath. “We started the troop and everyone was excited about it. About eight months later, the BSA ended our troop because of me being a gay scoutmaster and kicked out all the kids.”

After their expulsion from the BSA, McGrath and the kids went searching for a new program. “We saw BPSA as an inclusive option and were happy to make the change,” he said. “There are also no problems with having girls join, so we were able to be inclusive to LGBTQ and girls.”

Having boys and girls together, according to McGrath, can help create and foster an all-inclusive environment that appears to be a rarity these days. “It’s really fun to watch our kids as they compete. Sometimes they’ll self-segregate into boys and girls, but when they do it’s interesting to see that girls usually beat the boys,” said McGrath. “It’s great to see a little 10-year-old girl become the den leader of the boys and watch her really fill the role. Pretty inspiring.”

Jewett has voiced similar sentiments as he’s

It’s about: Are you a good person? Do you care about scouting? That’s all we require.

ANGELA PITTALUGAAida Foltz, above and right, and Kira Fryer, far right, read a compass and map to navigate a series of destinations throughout Mount Tabor Park in Portland as part of a lesson in orienteering skills for the Timberwolf Pack.

led his troop in Portland. “A thing I realized the very first time that I went out camping was that girls excel in the outdoors,” he said. “People who know the truth know that part of the game of excluding girls is to essentially make a safe space for boys.”

Jewett has spent most of his career working with children and believes an all-inclusive scouting program can be important. “Each [gender] will have a better measure of appreciation and respect for the other because they will have gone through these adventures and these hardships and seen the capabilities of each other, and that’s sort of how the real world is supposed to work anyway,” he said.

Scout law is laid out by the BSA as 12 goals to live up to every day, such as trustworthiness, helpfulness, bravery and cheerfulness. These notions are important to Jewett, who says his experiences in the Boy Scouts may have contradicted this promise. This is part of why it’s important to him to create a more inclusive environment. “My BSA summer camps were full of songs and jokes that were made at the expense of girls. So, one of the crazy things in the Me Too climate is the

sad way in which the boy-only culture of the BSA has not developed boys and men with the character that lives up to the scout law and scout’s promise, in so far as girls are not present,” said Jewett. “We need to protect a whole generation of boys from that. We need them not to be a part of it.”

Until August 2017, Eugene was not home to a BPSA troop. This changed when Angela Pittaluga wanted to find a program that both her 6-year-old son and 4-year-old daughter could participate in together. She joined the Rover Scouts of the BPSA, and as a scout leader was able to start her own troop, the 78th Emerald. Her son is a member of the Otter Scouts, while her daughter is a part of the still-unofficial Chipmunk Scouts. Though the troop only has four scouts at the moment, two girls and two boys, Pittaluga said she is confident in the experience she is giving the children.

“I knew that I wanted my kids in some sort of scouting program because I was in one and wanted to experience that with them. So I was excited when I saw the BPSA,” Pittaluga said. When she was in the Girl Scouts as a child,

her experience was much different than those of Jewett and McGrath in the Boy Scouts. “We mostly did arts and crafts. We went on a couple camping trips and went to Canada a couple of times,” she said.

Her experience with BPSA has been starkly different than those of her childhood with the Girl Scouts. “It’s a pretty even split,” she said. “It’s wonderful being a part of something that doesn’t really care [about gender]. It’s about: Are you a good person? Do you care about scouting? That’s all we require.”

For the future, Pittaluga has high hopes. “I want to foster equity and equality. Despite all our differences, we’re really all just the same. But we need to celebrate our differences while not excluding what makes us unique,” she said. Additionally, Pittaluga encourages the children in her troop in find whatever future they can conceive. “I use the motto ‘Follow your Bliss’ and I want to help people do that,” she said. f

STORY AUBREY BULKELEY | PHOTOS MIRANDA DAVIDUK

STORY AUBREY BULKELEY | PHOTOS MIRANDA DAVIDUK

Alice Greenberg, a UO doctoral candidate of physics, spends a Saturday afternoon in the dark basement of Huestias Hall in the CAMCOR lab. Greenberg co-founded the UO Women in Physics Group.

Alice Greenberg, a UO doctoral candidate of physics, spends a Saturday afternoon in the dark basement of Huestias Hall in the CAMCOR lab. Greenberg co-founded the UO Women in Physics Group.

As graduate student Lisa Eytel marches into a classroom at the University of Oregon with seven elementary-aged girls following like a row of ducklings, she asks, “Where are the cookies?”

With this question, Eytel launches the hands-on science lessons for the day. She will teach the girls basic forensic science techniques to discover who “stole” the package of cookies in a program called Girls’ Science Adventures.

On this particular Saturday, the fourththrough-sixth grade girls learn how to analyze fingerprints and handwriting samples to eliminate cookie thief suspects. They also perform a process called chromatography, which separates the different components

of ink to determine the pen that was used to write the ransom note.

The program is a collaboration between Eugene Science Center and UO Women in Graduate Science, a professional development organization for which Eytel is an outreach coordinator. ESC Education Director Karyn Knecht said the goal of the six-week program is to “develop confidence and STEM identities with young girls.”

A 2013 study by the National Science Foundation found males scored slightly higher than females in science as early as fourth grade. This trend continued as students progressed higher in education. The NSF also reported in 2015 that only 28 percent of all workers in science and engineering occupations were women. Initiatives to address this disparity have increased in recent years. Groups like UOWGS are working, both within the university and outside it, to increase gender equality in the STEM subjects—science, technology, engineering and mathematics.

According to Eytel, the focus is on grades four through six because studies have shown this age range is “the most formative and where girls’ interest in the STEM subjects start to fall off dramatically.”

Girls may be less inclined to continue studying STEM subjects due to peer pressure at this age, Eytel said. They also do not see many representations of themselves within the STEM fields. “So our outreach programs are saying, ‘Hey look, there are people other than just cis white men in these fields,’” Eytel said.

Eytel saw the issue of gender representation in her own educational experience. In elementary school her science teachers were women, but as she continued in her science studies men became more prevalent.

For her undergraduate work, Eytel attended Russell Sage College, an allwomen’s school in Troy, New York. She said one of the determining factors for her choice was the school’s strong forensic science program. While there, she focused on chemistry and forensics, and because it was a small school Eytel took courses at a partner college that was co-ed.

One was an advanced genetics course that was nearly balanced in gender, yet in

Aspiring plant scientist Kora Purdy, 9, observes a magnified fossil at the University of Oregon Museum of Natural and Cultural History.

Aspiring plant scientist Kora Purdy, 9, observes a magnified fossil at the University of Oregon Museum of Natural and Cultural History.

her observation, the men dominated the discussion during class. The distinction between this course and all-female ones was obvious. “Men were the ones that were speaking up more and more… and that was just a stark contrast to what I had seen over the past couple years,” Eytel said.

During a lab discussion for the same class, Eytel said a male student answered a question incorrectly one day, and when a female student corrected him, “he snapped at her and made a snide remark.” This shocked Eytel because “any comments that have an inkling of sexism at RSC get knocked down immediately by other students and the women are taught and encouraged to ‘take up space’ in the classroom.”

After finishing her undergraduate studies in 2014, Eytel visited potential schools with PhD programs in chemistry, specifically those with synthetic organic chemistry labs. While comparing programs, she examined the male-to-female ratios in both the professor and student levels. She also looked to see if women were working in the labs because she felt it reflected the culture of the department.

On a visit to one university that was recruiting her, she asked a male grad student why “there was only one woman in the lab of 20 people.” He replied, “Well, girls don’t do organic chemistry.”

“I was flabbergasted,” she said. “I really wanted to argue with the student. I was angry

There are laws to outlaw the obvious. Now we are left with the things that are more subtle.

SARA HODGESKara Zappitelli, co-founder of UO Women in Physics and fourth-year graduate student in physics, prepares her sterile lab area.

and shocked that I, a female who was doing undergraduate research in synthetic organic chemistry and hoped to pursue a graduate degree in the field, was told that I didn’t belong by a fellow student.”

These experiences made Eytel even more vocal. She said society discourages girls from speaking up and asking questions, and “that alone leads to fewer girls building the communication and the thinking processes leading into science.” But leading programs like Girls’ Science Adventures is her way of encouraging girls and influencing the next generation.

Sara Hodges, interim vice provost and dean of the UO Graduate School, has also observed gender bias. As a child, she would run through the halls of Vanderbilt University, where her father was a medical librarian, and count how many women were in each class picture of medical students. Women were significantly underrepresented in many of them. Hodges used this example to illustrate implicit bias, which is the result of repeated messages of cultural norms. If men are the only gender being represented in science, whether in schools, work or popular culture, then people will begin to infer that men are the only ones who can be scientists.

Today, Hodges holds a PhD in psychology, but she remembers when women weren’t even allowed to enroll in higher education. Hodges acknowledged that implicit bias is a complex and intricate problem that is getting more challenging to solve. “There are laws to outlaw the obvious. Now we are left with the things that are more subtle,” Hodges said.

Hodges has studied how perceived effort factored in the success of men and women in STEM fields. She explained that women tend to perceive that they put in more effort than both their male and female counterparts. This led them to have ‘imposter syndrome’ or the belief that they don’t belong. Rather than thinking the challenges they faced were a normal experience that everyone went through, the women assumed the problems were ones that only they encountered.

“It’s the moments of doubt that make the difference,” Hodges says. “What are you telling yourself when you feel you don’t belong?” This moment can be a

decision point as to whether a woman continues in a traditionally male-dominated field like science, or not.

Hodges identified the UO mathematics department, which currently has 13 women in its 57-person faculty, as one that is disproportionately male and may have something to share about the struggles involved with this disparity. However, the Association for Women in Mathematics’ UO chapter declined to comment, saying, “it would be inappropriate for us to have this conversation publicly, due to the changing climate in our department.”

Of the 100 women who attended the 2016 Pacific Northwest Women in Science Retreat hosted by UOWGS, Alice Greenberg, Amanda Steinhebel and Kara Zappitelli were three of only five women from the physics field. According to Steinhebel, the three founded the University of Oregon Women in Physics (WIP) organization after the retreat to “create a supportive network of women in the department, so people feel like they belong and are not isolated.”

UOWGS President Andrea Steiger said the group was founded 14 years ago in the chemistry department and is still “heavily linked” with it. She said the chemistry department is lucky.

“While we don’t have many female faculty members, we have a lot of faculty members that are very supportive and really, really trying to get to a really good 50:50,” said Steiger. According to her, most science departments at the UO, such as the physics department, are aware of the gender imbalance and are working to make it better.

Even though physics is making an effort, women are still notably underrepresented, both at UO and in the field overall.

According to the UO physics department website, there are two women tenure-related faculty members out of 34 total. In 2017, just 12 percent of the admitted graduate students in the department were women. This year, that number grew to 19 percent, according to Steinhebel. But the national average for women in physics is 20 percent. “We’re striving for the bare minimum. We just want to be average,” said Zappitelli.

It took the women time and a lot of conversations to start to convince the men in the department there was an issue. “Science people want concrete examples, but we don’t have the perfect example,” said Greenberg. Although according to Zappitelli, they had a good illustration of the gender imbalance two years ago when the physics department admitted zero women into the graduate program.

WIP has also been vocal about the need to hire more women faculty. “We’ve inserted ourselves in the hiring process,” said Greenberg.

In January, the three women hosted the Conference for Undergraduate Women in Physics, a regional event hosted by a different university each year in conjunction with the American Physical Society. According to its website, the goal of the APS is to help undergraduate women gain “information about graduate school and professions in physics, and access to other women in physics of all ages with whom they can share experiences, advice and ideas.”

Over 200 undergraduate physics majors from the Pacific Northwest attended.

Outreach like this is the positive momentum women in STEM need to overcome a legacy of bias against them. Hodges, too, believes in positive action to change implicit bias. She said, “To counteract it, we must do explicit things.”

We’re striving for the bare minimum. We just want to be average.

KARA ZAPPITELLIFrom left to right, Emma DeCicco, Brianna Jecklin and Charlie Fox observe ink separation as part of a forensic science workshop.

Bobbie and Brady Esplin enjoy a kiss on a children's swing set while walking their dogs in the park.

Bobbie and Brady Esplin enjoy a kiss on a children's swing set while walking their dogs in the park.

You’ll change your mind one day.” Check.

“Well, it’s different when it’s your child.” Check.

“Who’s going to take care of you when you get older?” Check.

“But you’d be such a great parent!” Check.

And just like that, you have a BINGO.

For those who are childfree—people who make the choice to forego parenthood for various reasons—being “BINGO-ed” is a common occurrence. Bobbie and Brady Esplin, a married childfree couple in their mid-30s and living in Sweet Home, say they’ve experienced these responses from others—including their former doctor— who don’t agree with their choice to opt out of parenthood. Brady says, “You can sit there and have a conversation and be like, I’ve been BINGO-ed! It’s amazing how people are so concerned with your reproductive behavior.”

But despite being ostracized by some, the Esplins have found a judgment-free community on Meetup.com, a social organizing platform of other “childfree” adults with whom they can hang out and socialize. The group created BINGO sheets with each square representing responses they receive when they reveal they don’t want kids.

More and more young couples like the Esplins are choosing to be childfree. Although one-infive women in the United States today will enter

menopause without having a child—compared with one-in-10 in the 1970s—the stigma of choosing to be childfree remains dominant.

Sweet Home, where the Esplins live, is a small town of predominantly traditional families that usually include a few kids. Their neighbors don’t know about their childfree choice. Instead, when people ask when they’re going to start having babies, Bobbie and Brady politely say they’re thinking about it. They’ve thought about it a lot throughout their lives. They almost had kids at the beginning of their marriage four years ago and even had names picked out just in case, feeling pressured by what they thought they “should do.”

Similar pressures exist well before marriage. Ashley Wilson, a senior at the University of Oregon, is studying to become a social worker and says she loves children. “I’ve volunteered and worked with them for years. They bring so much happiness to my life. But I don’t want to lose myself in being a mother. I want to stay ‘me,’” Wilson says.

“I know I have a choice, but at the same time it’s assumed that I’m going to have [kids] one day,” Wilson says. “I wish the choice was more of an actual choice, and less of a judgment if I decide to say no in the end.”

For the Esplins, one of the main reasons for not having children was the memories of their own childhood. For Bobbie, 35, the experience of

How one Eugene Meetup group’s members are normalizing—and celebrating—kid-free adulthood

raising her newborn sister at the age of 12 during her parents’ divorce forced her to be “parentified” at a young age. She’s been a caregiver and doesn’t wish to do it again.

For Brady, 33, he says his experiences growing up in what he called a conservative Christian cult and suffering mental, physical and sexual abuse have inflicted lasting scars, including struggles with PTSD and depression. As Brady was growing up, his family took in foster children who often had severe special needs, and he, like Bobbie, was forced into an early parental role.

The pair found each other on OkCupid. Bobbie’s dating profile helped weed out people who wanted children in the future. She wrote in her bio: “don’t waste my time if you want children.”

Later in their relationship, they each decided to undergo surgical sterilization. Brady looked into a vasectomy; Bobbie went in to see her doctor for a tubal ligation. While Brady’s procedure was quick, simple and unobtrusive, Bobbie says she was asked a series of probing questions by the first doctor from whom she sought the treatment. The doctor insisted that Bobbie would eventually change her mind and regret the procedure. Bobbie says she tried to convince the doctor that this wasn’t the case, and that her husband had already been sterilized himself. “Well, you might change your mind about him too,” the doctor responded, according to Bobbie.

After deciding to leave that doctor because Bobbie felt uncomfortable, Bobbie and Brady

“rehearsed” their argument before meeting with another doctor. They thought of every question the doctor would ask Bobbie: Are you sure? Is this what you really want? Don’t you like children? Won’t you regret this when you’re older? This time, they were ready. After another round of questioning, the second doctor relented. However, after undergoing an MRI, the hospital told Bobbie that she had severe scarring of her uterus from a car accident a decade before. The likelihood of being able to carry a baby fullterm would have been incredibly small. Brady says, “We made the choice, but we found out we didn’t have a choice to begin with.”

Without kids, Bobbie and Brady have time to cultivate their goal of running what they call a “sustainability exhibition.” In the future they hope to live off-the-grid growing their own food, building a bed-and-breakfast with sustainable resources, utilizing hydroponics and documenting every step of the process so others can do the same. “That’s our dream,” Brady says. “That’s what keeps us going.”

As they work toward their goal of focusing on what matters to them, the couple realizes how much more difficult it would be if they’d chosen to have children. They are candid in their belief that the stress of being parents would have broken them up by now. Research shows that the rate of decline in relationship satisfaction is almost twice as steep for parents than for couples

We made the choice, but we found out we didn't have a choice to begin with.

BRADY ESPLINBobbie and Brady Esplin relax with their two "fur-kids" on their homemade sofa. The Esplins also built their dining table and bench themselves.

The Esplins’ tattoos signify their anniversary date and serve as permanent wedding bands. The couple just recently celebrated their six-year wedding anniversary.

without children. Further, Brady says he also feels that his history of mental illness and natural introversion would have most likely made him a bad father. In the darkest points of his life—dealing with childhood trauma and the often-horrific memories during his time in the military—he says the demands of parenthood may well have broken him.

“I would not be here today if we’d had kids, and we wouldn’t be together,” he says. “The main reaction I get from people is that I’d be such a good dad. And I give that impression because I’m not a dad. I don’t want a child to go through what I did.”

As of now, they’re nurturing a different kind of dream and working towards sustainable living in baby steps. He dehydrates food while she makes bread, their backyard is a leafy compost pile and almost every piece of furniture in their home is hand-made.

For Bobbie, their lifestyle reflects a conversation the two had while they were dating. Brady had asked her to think of the time when the she’d last done something that mattered to her. Bobbie recalled,

“When I was a kid my mother grew corn one year and my entire family sat on the front porch shucking corn. And it was just what we had to do. It felt like we actually did something because I’d helped my mom plant it, weed, feed, water and help it grow. And to shuck it and eat it the next day for dinner was—it was everything.”

The stigmas associated with being childfree are some of the reasons Carley Boyce, a high school counselor and childfree woman in her mid-30s, decided to create the Eugene Childfree by Choice social group. The group has quickly expanded and offers a place for childfree adults to attend trivia nights, concerts, wine tastings and more with people who don’t talk about their child’s baseball practices or their new baby’s potty-training schedule. The events Boyce plans are designed to celebrate the freedom and spontaneity of being an adult without children.

According to the U.S. Census Bureau’s Current Population Survey from 2014, 48

percent of women between 15 and 44 had never had children—the highest since the data was first collected in 1976 and up from 47 percent in 2012. The general U.S. fertility rate in 2016 was also at an all-time low.

However, as women make the choice to postpone or forego motherhood, a Pew Research Study from 2009 found that 38 percent of Americans say this trend is bad for society, up from 29 percent in 2007. Critics of the childfree lifestyle see it as selfserving and wasteful. For them, not bringing a child into the world when a person has the means to is selfish. Further, childfree Americans are often portrayed as living egocentric lives. Stereotypical images of an adult without kids sprawled on the beach without a care are often used to criticize people who simply choose not to bring more children into the world.

Boyce’s main reason for being childfree was the realization that just because she could have kids, didn’t mean she should. Boyce organized the Childfree by Choice group after multiple failed relationships, including a

divorce with a storyline much like the others: her partner wanted kids, but she didn’t. It was the third relationship that had ended because of the childfree decision she’d made at 18. She’s never regretted the choice and has spent her adult life reflecting on if she should—or even could—take on the role of mother.

But for Boyce, the answer was always no. She recognized that she wouldn’t be able to masterfully multitask 40+ hour work weeks, maintain a home and raise a family while also caring for herself. She feels like she’d have to compromise parts of her life: traveling, going on spontaneous adventures, getting a full night’s sleep and practicing self-care.

The choice has proven difficult to maintain in her relationships. She recalls a previous broken engagement to a partner, saying, “[I was] just trying to push through it and fake it until I made it. Promising a wedding, babies and a house in the future. I loved him so much. I really tried to force my internal feelings on the matter to fit with him, and with society.” She says the temptation of giving someone she loves a child has been

there, but she also knows that sometimes it’s a short-term source of happiness before resentment, divorce and custody battles ensue. She’s experienced the fallout that can occur after a breakup and says, “If I can avoid the pain it would cause everyone, most importantly [a] baby, then that is what I’ll do. I wish I could be what society wants me to be and what I see on TV, but reality is that just isn’t me and I’m accepting that.”

She turned to the internet for affirmation about her choice because even talking about it with her friends was uncomfortable; they’d often say things straight off the childfree BINGO card. She felt alone with the lingering thought that something was wrong with her because she’d never wanted something that defines so many people’s lives. But what she found online were people who were just like her—and they weren’t ashamed. Boyce felt validated. Before this, she could count the number of times on one hand in which someone had told her they’d never wanted kids. She says, “My head would always snap right up and I would stare at

them in awe. It was like finding a unicorn.” After seeing social groups for childfree people in other cities, she created a public page for Eugene-area “no-kidders” to connect.

Boyce sees the moniker of being “selfish” as the biggest misconception about her childfree choice. At her job as a counselor, she has seen hundreds of high school students through graduation, and because she has the time at home to rest, recharge and practice self-care without the stress and labor of her own children, she says she has the energy to provide support to students going through tough times in their own lives. She says she feels like Charlotte from “Charlotte’s Web,” with all the little spiders that fly off to their futures after their short time with her.

Boyce is looking forward to the day when she finds a partner who accepts her childfree choice. She says, “I now know to the core that I need to find someone who is okay with just me. I’ve never known a relationship like that, where the pressure to do something I simply cannot isn’t there. What must that kind of love be like? Unconditional.” f

Avi Yocheved’s journey of self- empowerment as a non-binary person in a gendered world

They/Them/Theirs

Like many non-binary people, Avi uses these pronouns instead of he/him/his or she/ her/hers as they don’t identify with male or female pronouns.

ithout thinking about it, Avi Yocheved put their red and grey men’s swim trunks on underneath their clothes so they wouldn’t have to change in the locker room. Despite their love for swimming, they hadn’t been to the pool in two years. As Yocheved headed toward chlorine-filled waters, a mixture of nerves and excitement filled their body.

They left with a large group of their friends from the Gender Equity Hall at the University of Oregon. Like them, the others in the group hadn’t been to a pool in a long time.

“There’s safety in numbers,” Yocheved said. This was the thought that drove this group to participate in an activity that so many of them loved but had been barred from because of it being an inherently gendered experience — a situation where stepping outside the binary of being a man or a woman can have major social consequences.

There is a set of rules that governs behavior, expectations and identities called the gender binary; an assertion that there are two and only two genders. It dictates whether someone is given a pink or blue blanket when they are born, dolls or trucks to play with and eventually, what they can do or say. Yocheved is genderqueer, one of many gender identities rooted in the feeling that they don’t fit the conventional “man” or “woman” category. Though data on genderqueer people is difficult to gather due to the gradations of identity in this group, this umbrella term is commonly used by nonbinary people, who were officially recognized by the state of Oregon in January. Gendernonconforming residents may now select “X,” a third gender option on an application for a drivers’ license, legally validating the identity of people like Yocheved.

Yocheved is 19 and a freshman majoring in pre-family and human services at the University of Oregon. They play the clarinet and are a slam poet and an event coordinator for LGBT student services. Their partner, who asked not to be named, describes them as someone who always puts their friends above all else: the type of person who “forgets to put their oxygen mask on first.” After college, they want to help other individuals

by developing a type of therapy specializing in recovery and healing from traumas brought on by gender-related experiences.

Though Yocheved doesn’t fit the gender binary, they live a lot like everyone else, with friends, hobbies and aspirations.

But as Yocheved and their floormates approached the locker rooms at the UO Student Recreation Center, their pool day became a lot more complicated. The task of choosing the women’s or men’s locker room can feel impossible when their identity lies somewhere in the middle of these two options.

Yocheved was set on avoiding the locker room because of past traumas associated with it. They were harassed and bullied in locker rooms throughout grade school, being called names and excluded by other girls. According to the 2011 National Transgender Discrimination Survey, this is common for gender non-conforming and transgender individuals. Fifty-one percent of respondents reported being harassed/bullied in school.

“I was constantly falling short of the ‘girl box,’” Yocheved said. To them, the “girl box” was full of all the characteristics and behaviors that they were expected to embody. To avoid alienation from their high school peers, they adopted what they consider hyper-feminine characteristics. Society’s demand for authentic girlhood meant living in a lie of makeup and boys in order to be accepted by the world.

Compensating with “hyper-femme” gender expression to find acceptance was deeply connected to their sexual identity too. They said that learning how to be feminine and fit inside of the “girl box” is linked to being heterosexual.

Yocheved was dealing with heteronormativity, the idea that heterosexuality is the social norm. In that construction lies a set roles for men and women, more commonly referred to as

Yocheved sits on their bed in the Gender Equity hall. The details on the walls reveal parts of their personality.

“gender roles.” According to the Center for Disease Control and Prevention, 97.7 percent of U.S. adults 18 years or older identify as straight, making heterosexuality the overwhelming majority. With that being the most common sexual orientation, sexualities outside of being straight can become “othered.”

Heteronormativity and the gender binary go hand-in-hand, interlacing with one another and complicating life for those who find their true selves outside of heterosexuality or the gender assigned at birth. Yocheved’s self-described fumbling with traditional femininity in high school was their attempt to go along with the norm and meet society’s demands on their gender and sexuality.

This fumbling was, and still can be, a daily experience. Simple experiences like going to the bathroom are complicated for someone who doesn’t identify as man or a woman. Going to the women’s bathroom is accompanied by people peering under the stall to see if Yocheved is a man and being told that they’re in the wrong restroom until Yocheved’s soft, feminine voice is heard in response. But the solution isn’t just heading into the other bathroom.

“I quickly realized that the men’s bathroom is a no-go.” Yocheved said they have been threatened and sexually harassed in the men’s bathroom. They then began seeking out gender-neutral bathrooms—not because this was the identity they came up with themself, but because they had been forced out of both male and female spaces.

In situations like these, Yocheved is still confronting the concept of the “girl box” — they don’t fit the characteristics of traditional femininity, nor do they conform to traditional masculinity.

But in their senior year of high school, Yocheved took a major step toward expressing the way they really felt. They cut off their hair and started dressing more androgynously. This self-liberation was the beginning of a long transformative process of healing. Part of this has been persevering in building their own narrative and withstanding the consequences of not quite fitting into what gender they were assigned to at birth. This, in essence, is what Yocheved hopes to help others do too.

For a gender-nonconforming person, finding spaces to comfortably exist in is an ongoing process. They have found healing in expressing themselves more “androgynously butch,” identifying as genderqueer and finding community by living in the Gender Equity Hall. This hall is a part of the UO’s LGBTQIA+ Scholars Hall, an Academic Residential Community (ARC) where incoming freshmen can choose to live with

students who have shared academic interests and values regarding gender and sexuality.

Visiting the pool and locker rooms at the UO Rec Center started as an obstacle for Yocheved and some of their dorm-mates. But through the community they share and the strength they derive from one another, they all were able to face it.

As Yocheved and their group of queer friends made their way to the pool for the first time in two years, they were ready to skip the locker room altogether and head straight for the water. They didn’t want to deal with having to explain to people that they actually belonged in the women’s room. But when one of their friends was afraid to go into the women’s locker room alone, Yocheved stepped up and accompanied them without hesitation. They became so focused on friendship and having fun that they forgot about the gendered experience of the locker room.

Of that moment, Yocheved said, “I felt like we could take up that space; like we deserved to be there.”

Yocheved walks with their partner, who declined to be named, in the afternoon light on the UO campus on the way to slam poetry practice.

Analog Barbershop in downtown Eugene, above left, is one of the places in which Yocheved takes comfort. There, they find affirmation in their identity without an uncomfortable focus on the identity itself.

Yocheved hosts LGBTea Time in the LGBTQIA Student Center on UO campus every other Wednesday.

Benjamin Wilkinson, Tigre Lusardi and Matt Tarnoff, from left to right, practice yoga on top of Wilkinson’s truck.

Benjamin Wilkinson, Tigre Lusardi and Matt Tarnoff, from left to right, practice yoga on top of Wilkinson’s truck.

In a neighborhood gym near the University of Oregon campus, a midday yoga class is in session. Four men and six women bend and stretch to Moby and Bon Iver on jewel-tone mats. Instructor Jess Donohue, 47, is all about encouraging her students. “Let yourself be amazed at what your body can do for you,” she says. “Make it your 100 percent, not your neighbor’s 100 percent. What will make YOU proud?”

The class is called “Broga.” Donohue says her classes are “for the bro in us all.” Yes, it’s branding, but it’s also an approach designed to make yoga more approachable and inclusive when at times it’s anything but.

Yoga is an ancient practice created in India by men, for men. The asanas, or physical poses intended to prepare the body to meditate have become popular in the Western world as a form of exercise. Nearly 30 percent of Americans have tried yoga, according to a 2016 survey of yoga in the United States conducted on behalf of Yoga Alliance. But step into a modern yoga class in Eugene or anywhere in the U.S. and you’ll see a room of mostly women. While the number of men practicing is growing, the survey showed that 72 percent of yoga students identify as female.

Despite these odds, those identifying as men are showing up on yoga mats more and more. Male yoga student ranks grew by 47 percent from 2012 to 2016, from around 19 percent to 28 percent of all students. To encourage this growth, studios and teachers are attempting to remove barriers to entry, such

as an exclusive feeling, a spiritual overtone or a focus on flexibility, which affect all genders but can disproportionately affect men.

Broga founder Robert Sidoti says too often men leave class with similar feelings toward yoga: “It’s not for me. It’s for chicks.”

He says men can have different reasons for going to yoga. Picture: “A typical 25-yearold woman offering a yoga class to a group that’s predominantly men in their 40s and 50s, and they’re aching and stressed. She’s talking about the chakras aligning and the heart space opening—these aren’t things that a man wants to hear in that moment. He wants to hear ‘this pose is helping your back feel better. If you keep practicing this, this breathing technique is going to help you manage stress and anxiety.’”

Sidoti came up with Broga 15 years ago in California to cater to men’s needs. In Broga’s curriculum, he relies on “functional movements” and doesn’t teach postures that have no everyday application, which means many of the traditional yoga asanas are thrown away. He says it’s purpose is to “teach and serve yoga up in a way— whether it’s postures, language, purpose or

intention—that men can show up for, be open to, digest and process.”

Beyond what benefits are offered in the class, many yoga poses demand a level of flexibility that doesn’t come easily, especially to some men. Jess Donohue is also a massage therapist who’s studied anatomy. Generally, she says male bodies tend to be less flexible than female ones, due to their narrower hips and larger muscles. Teachers don’t always accommodate these differences, making it easy for men to feel like underachievers in a yoga class.

The perceived inaccessibility of Western yoga has been influenced by media representations. On Instagram, yogis tend to model advanced versions of a pose and look serene while doing it. Additionally, men, non-binary people, people of color, older people and a variety of body types have been underrepresented in the media. A campaign called #whatayogilookslike is working toward a more inclusive image. The hashtag has been used more than 19,000 times.

For purists, yoga can be a spiritual practice. But for some of Donohue’s students, it’s nothing beyond a workout. Broga student

Larry Lewin, 68, says he’s “a-spiritual,” and that’s exactly who Broga is designed for. Donohue says it’s “accessible to people who would walk away from a room full of Hindu statues and lotus flowers.”

New Broga student Kurt Krueger, 61, says his masculine perspective is what kept him from trying yoga, which he perceived as weird, exotic and foreign. “For an old white guy, it’s hard to get into something generated in a different country and culture, with no specific connection to me. It’s unfamiliar,” says Krueger of yoga’s lineage.

When a gym staffer suggested he try the Broga class, Krueger said “Yoga? Come on, man…” But he says his generation’s oldschool male perspective is changing, and Broga is helping shift it for him. Unlike the team sports he grew up playing, Broga isn’t achievement-oriented. He can go at his own pace.

Other students are finding Broga to be a game-changer. Lewin says he’s tried yoga classes at different stages of his life, but they never “worked” for him. This was partly because he compared his ability to other students’ and tried to copy their poses.

“I don’t know what I’m doing so I make the classic mistake of looking at people near me who are much more flexible, and end up pulling a muscle and thinking I’m never going to do yoga again,” Lewin says of his past experiences.

Now, he says he walks out of Broga class feeling proud. “I did it again. I’m getting stronger.” These are Lewin’s mantras for his practice today.

Another student, Jesse Springer, 49, says Broga class makes him feel like he accomplished something. “Jess is somehow able to really challenge us to push hard, but at the same time give us permission to accept where we are. I don’t know how she does that, but it’s pretty cool,” he says.

And Donohue says her students get the same physical and mental benefits from coming to class, whether they think they’re exercising or engaging in spiritual practice.

“You go in thinking, ‘I just want a good workout,’ but you get the yoga anyway,” Donohue says.

Sidoti’s biggest critics have been the people most deeply involved in yoga, who feel Broga is disrespectful to yoga’s tradition and lineage. Though yoga teaches acceptance, Sidoti says “they’re the most judgmental and harsh.” He stopped listening to critics early on, choosing to focus on Broga’s mission of accessibility.

Sidoti views Broga as “a big wide open door and on-ramp into the world of yoga.” In his classes, he’s incorporated familiar

exercise moves like pushups into a format that also includes contemplative sections at the beginning and end of class.

He offers the variety because “the physical stuff is a little bit easier.” Sidoti says it becomes harder when he asks students to examine their relationship with themselves. “People don’t always necessarily want to do that,” Sidoti says.

But yoga’s core goals are steady breath, a focused mind, and emotional non-attachment to the outcome of your actions—the same goals as meditation, its sister practice. Sidoti’s hope is that people will come for the exercise and stay for the meditation, and over time they’ll be ready to explore the mindful side of yoga more comfortably.

Across the Willamette River in Springfield, studio owner Benjamin Wilkinson is also teaching a hybrid style of yoga he’s calling Common Core. Like the Broga teachers, Wilkinson has experienced the various barriers to getting any student, male or female, onto the mat.

He says the intersection between Broga and his brand is that both try to “take away

”

Life is so serious. It doesn’t have to be serious on the mat too.Standing in the front of the room on a small platform, Jess Donohue, 47, leads her weekly mid-day Broga class at local gym In Shape Athletic Club. JESS DONOHUE

those standard barriers to entry that have plagued men and just humans especially, in approaching mindful-oriented fitness-based classes.” His goal is to figure out what’s holding back each potential student.

In Wilkinson’s experience, a good approach is to offer his students familiar answers to the question “Why am I here?” He allows them to believe a story they’re comfortable with. He offers pop-up classes in non-traditional settings that focus on the functional workout aspect or include a mimosa or beer. Similar to Sidoti, Wilkinson sees this as a “gateway” approach.

His first yoga experience was all about the workout. “Honestly, I liked it because it kicked my ass. That was the first appeal,” Wilkinson says. As a guy now seeking a mindful yoga practice, Wilkinson has had to remind himself that growth can be difficult. Speaking for men, Wilkinson says “as soon as we open that crack of vulnerability in the yoga world, shit’s gonna come up,” referring to suppressed feelings.

“For me, coming out of camel pose crying? That’s not a cool place to be for a guy,” Wilkinson says. Sometimes, extreme stretching such as in camel pose, which is a backbend or “heart opener,” can

release deeply held emotions. Tears on the mat can happen—not from pain, but from the release of tension.

Wilkinson acknowledges that despite his barriers, as a man he benefits from privilege.

“I’m very aware of the fact that as a white, male American I’ve been gifted too much. All I can choose to do, in addition to being active socially and politically, is listen, be humble, and be quiet, and be vulnerable.”

On his journey from yoga student to teacher to studio owner, Wilkinson has made peace with some pretenses of yoga he previously rejected. Assimilating into yoga’s culture was part of evolving “as a male who now will call himself a yogi—who, years ago, laughed at that term. I don’t know at what point I checked my concern and just became a yoga person,” he says of his experience.

Ten years ago, you wouldn’t have caught him saying namaste, either. “I said ‘peace.’ Because if I say ‘Namaste,’ I might be cultconverted into something I’ve not agreed to,” says Wilkinson. Namaste is a Sanskrit word collectively uttered at the end of yoga classes, meaning “the light in me honors the light in you.”

Now that he’s accepted some of yoga’s traditions, he’s here to break others.Wilkinson

recently opened Common Bond, a “human yoga studio”. By this, he means it’s unpretentious.

“We have cracks and sawdust and a weird ceiling and concrete. It’s not a pristine environment; it’s not a space that you can control. It’s like life,” Wilkinson says of the studio’s “grandpa-chic” aesthetic. He’s got a set of GI Joe army figurines in yoga poses and a row of upcycled gym lockers in the lounge.

His self-declared strengths are “casual, conversational, relational teaching.” This goes against a more formal, one-directional approach in traditional yoga.

Donohue also pushes back against formalities. She won’t say namaste. She explains why: “It’s not my religion, not my language. It feels like I’d be pretending to be something I’m not,” Donohue says.

So how does she end class? “Sometimes I say, ‘May the force be with you.’ And people laugh. That’s another thing too: life is so serious. It doesn’t have to be serious on the mat too. So, if I can throw a little humor in there and have people have a sense of humor about themselves...Hooray.” Visit

It’s not a pristine environment; it’s not a space that you can control. It’s like life.”

BENJAMIN WILKINSON

UO alum Jesse Donohue, 43, periodically yelled out, “Fish sauce!” triggering laughter from the Broga class. Instructor Jess Donohue, his wife, explained that sometimes a tough workout is like fish sauce—it stinks but you just have to grin and bear it.

Del Hawkins relaxes in Savasana, also known as corpse pose, at the end of Broga class. This is typically the final pose in yoga classes and offers a few minutes of relaxation before class ends.

Katie Sheehan and her teammates gather around a pinball machine during a tournament. Headquartered at Blairally Vintage Arcade, they meet every Tuesday to practice in the Eugene chapter of the Belles and Chimes pinball league.

rriving in Eugene five years ago, Katie Sheehan and her boyfriend Andy Marler had a mission: They wanted to find a fun way to plug into the community and make new friends. Blairally Vintage Arcade was only a few blocks from where they lived, so they stopped inside one evening. Marler was already a pinball player, but Sheehan had never touched a pinball machine. That night Sheehan befriended a competitive player and was invited to play. After several games she quickly found her passion for pinball and the community that surrounds this niche sport.

“It was fun, so I got more involved,” Sheehan said. “But there were no other women playing.” After that first night Sheehan competed for over four years and officiated for one year in mixed-gender leagues. With change in mind, in 2015 she helped usher more women into competitive pinball by co-founding the Belles and Chimes all-women’s pinball league of Eugene with Kristine Morgan, another player. Working with Chad Boutin, owner of Blairally, they gained sponsorship for the Eugene chapter, which is the ninth addition nationally to the Belles and Chimes all-women’s leagues.

According to them, a major benefit to an all-women’s pinball league is that it provides women the freedom to play without men overshadowing them. For many years, pinball was mostly a men’s competition. With women making up just 12 percent of players in the International Flipper Pinball Association, the game is still nowhere near equal. Competitive pinball, unlike most male-dominated sports, isn’t won by physical strength, yet as Sheehan put it, “for a long time now this has been a boy’s club.” She said that in the past, men’s aggressive style of competitiveness and preexisting pockets of sexism towards female players pushed women away from this sport. But that’s changing. Women across the country are addressing this problem by starting women’s leagues of their own and driving new interest in competitive pinball.

In past mixed tournaments, Sheehan and Marler said they witnessed some men being too forward in arcades around Eugene, making women competitors uncomfortable. But both further explained how these types of

players get sorted out quickly at places like Blairally where other players will step in and put a stop to any misconduct. Another issue occurs when female players are treated as inferior. “Women’s skills aren’t taken seriously,” said Portland Belles and Chimes league member Zoe Vrabel. Vrabel is ranked third in the women’s IFPA World Pinball Player Rankings and 213th overall in the IFPA’s mixed league. Vrabel said women’s leagues create a more welcoming space compared to a mixed league’s. “We don’t want to be treated like we’re on Tinder when we’re just here to play pinball,” she said.

Getting hit on isn’t the only way women players are belittled. When Belles and Chimes Eugene was first established, Sheehan, 29, said she occasionally dealt with a male player at Blairally who was much older and more experienced. Over the age of 50 then, he had

been playing since he was 10. Sheehan, and Marler said they felt he treated most new male players with respect. But he treated female players differently to the point of telling Sheehan that she wouldn’t understand his ideas on pinball when she asked for his advice on a machine. “He talked to me condescendingly,” she said.

During mixed tournaments, Vrabel witnessed men acting out aggressively and said they were often vocal with their anger. Many players, including Sheehan, felt these actions made women apprehensive about pursuing competitive pinball. But Vrabel said she enjoys the Belles and Chimes because “it’s a more warm and accepting environment.” She explained how some men she’d spoken with would also prefer the cordial atmosphere that women’s leagues like Belles and Chimes offer.

Travis Kerr, a mixed-league competitor at Blairally, said that “a deeper feeling of comradery is in the women’s leagues.” Eugene Belles and Chimes Facebook page makes this clear: “All women are welcome, free from labels or characterization.”

With the growth of women’s competitive pinball leagues, the IFPA decided to sanction women’s-only events in December 2016. Creating all-women’s leagues presents an opportunity where it didn’t previously exist. “The women-only angle allows women to get off the bench,” said Josh Sharpe, president of the IFPA. The first all-women’s championship took place in Las Vegas on March 1, 2018. The top 24 women with the most IFPA points competed for cash and reputation.

Some women in Belles and Chimes are just starting out, and want to learn in a welcoming environment. Sheehan explained

that three members of Belles and Chimes Eugene only want to play in the women’s league because “they don’t feel comfortable playing with that level of competition and the number of players.”

Even if some aren’t interested in competing outside of women’s-only leagues, others want to win in both. “When I get better, I want to compete in mixed leagues,” said Eugene league member Alysha Shipley. She started playing with the Belles and Chimes about six months ago.

Published in 2011, an economics article written by Stanford researchers Muriel Niederle and Lise Vesterlund titled “Gender and Competition” points to one possible reason women weren’t previously thriving in competitive pinball: confidence levels.

This comprehensive study found that when it comes to competition in problemsolving tasks, men show significantly higher levels of confidence compared to women even though their abilities may be the same. It also found that confidence increases the likelihood of someone entering a contest. This results in more low-skilled men entering tournaments due to overconfidence. Meanwhile, highskilled, under-confident women enter tournaments less often.

Sensory physiologist Dr. Jagdeep KaurBala, who teaches in the psychology department at the University of Oregon, also pointed out that women will underrate their confidence while men will overrate theirs. According to Kaur-Bala, once in a competition, it’s also been shown that men and women exhibit aggression differently. She said that research finds men and women to

be equally aggressive, yet men exhibit physical aggression while women exhibit instrumental aggression, a type used to achieve goals that is more passive. Despite men and women having different strategies, the lack of physical abilities required in competitive pinball means winning should be a matter of skill that anyone can achieve through practice. Niederle and Vesterlund provide one reason behind varying levels of confidence. Evidence suggests that people’s preferences for competition are influenced by the way they’re raised as children—in other words, nurture, not nature. This points to another study written by sports psychology professor Linda Bunker and published in 1991 through The Elementary School Journal. Bunker focused on building children’s self-confidence and self-esteem through the role of play and motor skill development. The results:

Our league allows us to have fun in a more relaxed environment.

With an adult’s healthy encouragement and proper corrective feedback for any given activity, a child’s confidence will improve, which helps grow their skills. An environment such as Belles and Chimes is a later-in-life example of a more supportive approach to competition.

LEAGUE OF THEIR OWN

Luna O’Neal, a player who competes with Belles and Chimes Eugene, plays in both mixed leagues and all-women’s leagues. O’Neal said she felt an obvious tenderness within women’s leagues in comparison to the mixed leagues. “We’re all human, so it doesn’t matter to me. But there is a lot of testosterone in co-ed pinball,” she said.

Jamie Blair, another Belles and Chimes member, doesn’t like playing in mixed leagues because men have made fun of her in the past. She joined the Eugene chapter after she moved from Los Angeles over a year ago. “I was looking for something cool. I came for the pinball at Blairally, then Katie saw me playing and said, ‘Hey, you’re pretty good.’” Blair isn’t a fan of computer games or anything resembling sitting around, but she’s also not interested in extremely active sports.

“I’m 39, I drink, and I smoke,” she said as she smiled and took a sip of her beer.

Belles and Chimes co-founder Kristine Morgan had similar sentiments about playing in women’s leagues. “Our league allows us to have fun in a more relaxed environment,” she said.

During an early March 2018 mixed tournament at Blairally for IFPA points, everyone who took to the machines had their own runner’s stance with one foot back and front knee slightly bent. Some players threw their hands up in anger when success escaped them after a rapid tapping of flipper buttons. One player even flipped off the machine as he walked away.

In mixed tournaments, Sheehan and Marler noticed some men hit the sides of pinball machines after losing. But Sheehan said this doesn’t happen in women’s leagues. She’s never seen a woman “smash” a machine, though she did admit that occasionally “I put my hands up like I’m about to smash the

machine, but I just put them down.”

On the final night of the season, the women of Belles and Chimes stood together inside Blairally. With excitement, they wore new team hoodies with their logo on the backside, which was inspired by the classic multi-pointed star that’s painted on the top of pop-bumpers.

Jurassic Park was their first battleground that night. Pulling a spring-loaded plunger, the first contender released her fingers from the handle. A metal ball sped off. Lights started to blink, bumpers popped, bells rang; that shiny ball danced around the board with the unrelenting tapping of a woman’s fingers behind two classic arcade flipper-buttons. To beat the machine, said Sheehan, “it only takes one good ball.”

We don’t want to be treated like we’re on Tinder when we’re just here to play pinball.

ZOE VRABEL

Katie Sheehan next to one of the pinball machines in Blairally Vintage Arcade.

Katie Sheehan next to one of the pinball machines in Blairally Vintage Arcade.