19 minute read

Keith Frank: On the Pulse of Zydeco

DAVID SIMPSON

Keith Frank

Advertisement

On the Pulse of Zydeco

An abridged version of the Keith Frank story in Update! #88

KEITH FRANK has been at the forefront as a zydeco showman for more than three decades, a pioneer of nouveau zydeco, and an innovator of recording production techniques. I googled ‘nouveau zydeco’ and the first result listed was “Nouveau Zydeco: Keith Frank Gets It On,” a 1995 story for OffBeat Magazine by Michael Tisserand. While other artists have made their livings touring to festivals and other gigs around the world, Keith Frank has chosen to perform mostly on his own turf, and he’s been the top draw at southwest Louisiana venues like Slim’s Y-Ki-Ki nd Richard’s Club. His mix of R&B, rap, reggae and zydeco has been hugely successful in attracting a young fan base, and his keen sense of playing to the dance crowd appeals to an older audience as well. Keith Frank, the “Zydeco Boss,” has done about as much as any zydeco artist in the history of the genre.

Michael Tisserand analyzed the Keith Frank performance. “In Keith Frank’s Soileau Zydeco, many songs are instrumentals, and even when he’s bearing down on his accordion, the effect is light and bouncy — perfect for dancing. He’s a large man with a jovial face and a trace of a beard, but you don’t really notice this during

his show. If you watch him at all, you realize that he is expertly playing the club, guiding the dancers through the evening, basing his songs on familiar accordion riffs, keeping his crowd on its toes by throwing in a few fresh licks and humorous pop music references.”

In the book, The Kingdom of Zydeco, Michael Tisserand covered the genesis of the Frank family in Louisiana music. Keith Frank grew up in a musical family. The Preston Frank Swallow Band — which included Keith’s father, Preston, on accordion, his great-uncle, Carlton Frank, on fiddle, and another great-uncle, Hampton Frank, on guitar — was best known for the song “Why Do You Want to Make Me Cry?” composed by Preston with drummer Leo “the Bull” Thomas (Leroy Thomas’ dad), and adapted from Bois Sec Ardoin and Canray Fontenot’s bluesy “’Tit monde.” Thirty years ago, the song was covered by nearly every zydeco band. Nathan Williams recast it as “Why You Wanna Make Poor Cha Cha Cry?”

The Preston Frank family band was organized in 1977, but Preston wasn’t the first in the family lineage to play music.

Preston Frank’s great-grandfather, Joseph Frank Jr., was an accordion player, and his great-greatgrandfather Joseph Frank Sr. was known to be a fiddler. But they never recorded. “He would play a fiddle real good, my daddy and them told me,” Preston recalled. “But he was never recognized, they never had anything said about him. He was there at the time when Dennis McGee and Amédé Ardoin were playing. Maybe Keith Frank in 2018 there was some kind of way they got it from him, and he didn’t get the recognition.”

In the ’80s Preston Frank’s job at a plywood mill wasn’t giving him much time for playing music, “So I told Keith to do what he needs to do.”

For the past three decades, the Frank name in music has largely rested on Keith’s shoulders. “I fought so hard to keep

playing, and once Keith got himself established, then I kind of backed off,” Preston explained.

“I started Keith young. He played my style at first, then he changed to Boozoo’s style, then he went to another style, then he went to his own style. But there’s still some of me in there. When I’m determined to do something and make something, I don’t give it up until I accomplish what I want. Keith’s like that. We’ve come a long ways. We’re recognized now, but we sure worked like hell to get that recognition.”

Keith Frank was four years old when he first played drums behind his father, and he became his full-time drummer when he turned nine. But zydeco was not his first love.

“I hated it,” Keith said, laughing. “I swear, I hated it. I could not stand playing music. I hated zydeco, I hated the whole thing. My old man would make me practice, and I could always find something better to be doing. Then as things moved on, my dad started playing less and less. Then I realized it’s a part of my life, and I couldn’t stand being without it.”

By the time he started in Oberlin High School, Frank had his own band and was entering talent contests.

On marching band trips, when other students brought radios, Frank brought his accordion. “On the way there, I would play on the bus, play in the band room. People would laugh, say it was hilarious. I didn’t think it was funny. But back then, “Boozoo became my idol — if you played accordions, they well, my daddy is my idol, laughed at you and called it but Boozoo was up there. country music. A lot of the

And then Zydeco Force people spoke French, but they started coming on the didn’t want anybody to know scene.” it. In fact, if I went back and played in Oberlin, I’d get no support at all. But I don’t let it bother me.”

Early on, Frank was inspired when he saw Boozoo Chavis on the comeback trail. “Sometimes we were the only young ones in the place, me and my sister,” he says. “Boozoo became my idol — well, my daddy is my idol, but Boozoo was up there. And then Zydeco Force started coming on the scene.”

When Preston Frank began performing less frequently, Keith started playing guitar in Jo Jo Reed’s band. With his father’s approval, he switched to accordion and began fronting the family band, which included his sister Jennifer on bass and his brother Brad on drums.

“I didn’t really take it over,” he says. “We had two separate groups with the same people, but two totally different styles. My dad plays the real zydeco. Traditional. He does some Clifton, his own stuff, and the stuff that’s been handed down in French.”

Beginning in 1982, the Preston Frank Family Band made a series of records with Lee Lavergne on the Lanor Label, ending with Let’s Dance in 1991.

Lavergne recalled, “They were good little kids, because the mama and the daddy, they raised them very strict. They would always come around, and I told Keith one day, ‘You kids ought to get together and do something.’ They played a little bit different than their daddy, and they were doing jobs without their daddy, because Preston worked shift work and was tied down.” Keith Frank and the Soileau Zydeco Band recorded one cassette for Lanor, On the Bandstand. The tape included a revised version

of Amédé Ardoin’s “Two Step de Prairie Soileau,” as well as songs influenced by Boozoo Chavis and Zydeco Force. “They were searching for something different,” remembers Lavergne. The relationship between the producer and the young bandleader quickly broke down, however, and they never worked together again. “It never could be loud enough on the drum for him,” Lavergne explains. “He wanted the drums to be heavy, and I like them heavy, too. But you don’t send those needles into the red and distort. I’m concerned about the quality of the sound. But he wanted to do things his way, and we didn’t get along about that, and he went and did his thing with somebody else. And he done good, you know.”

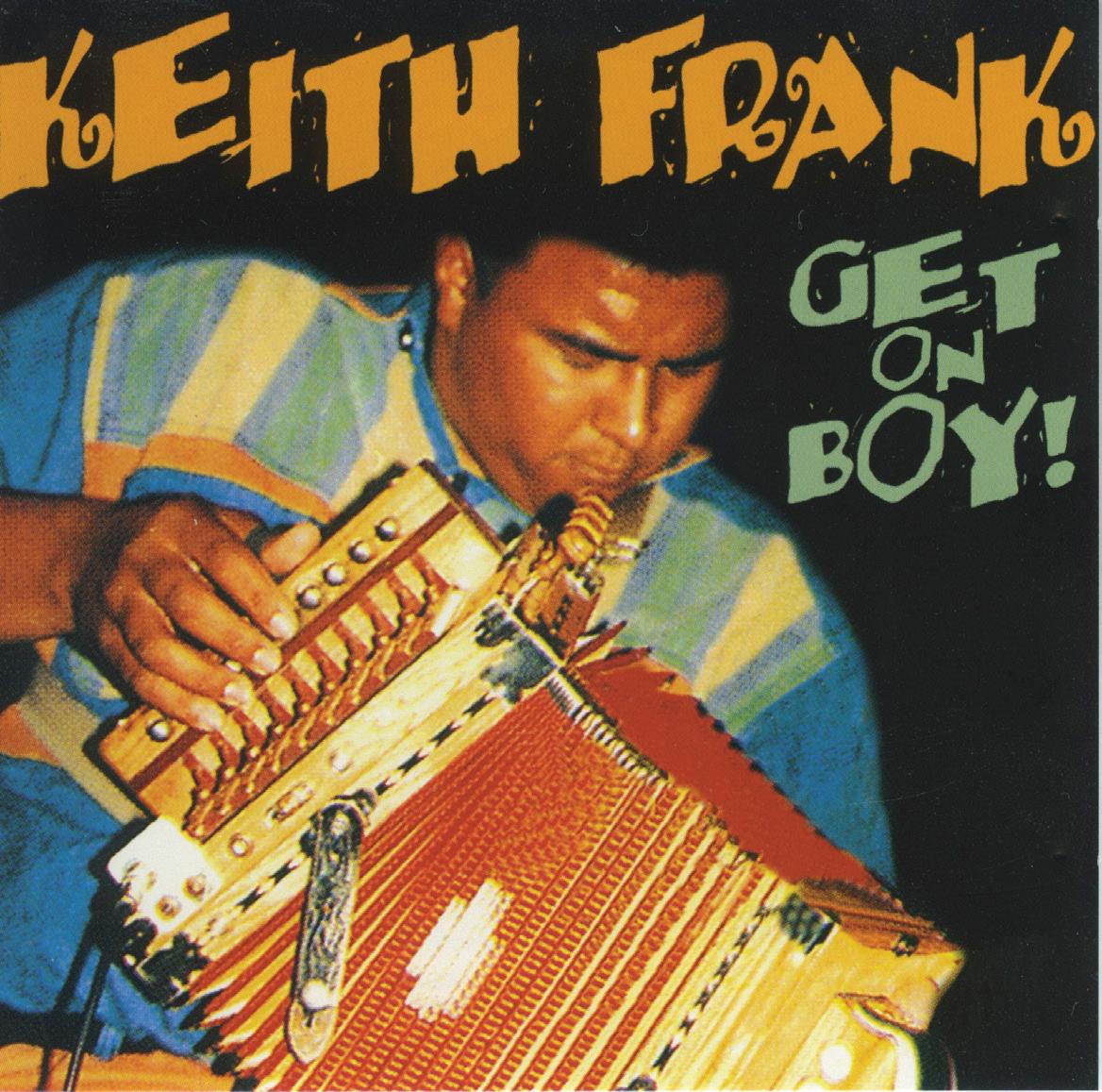

In 1993 Keith Frank searched for a place where he could do it his way, and he launched a long-standing partnership with Eunice-based producer Fred Charlie and sound engineer Scott

Ardoin. He took an active role in every stage of the production, resulting in Get On Boy! The album showcased Frank’s new sound, and the title became his nickname. He reworked Boozoo Chavis’ “Zydeco Hee Haw” into his own “Murdock,” and D. L. Menard’s Cajun classic “The Back Door” into an instrumental called “Huh.”

He was most inventive in songs like “Going to McDonald’s,” in which he chose to portray modern Creole life as he knew it. “I wrote that song at a trail ride,” he remembers. “I hadn’t had a thing to eat all day, and they had this cowboy stew or something like that, and then somebody came in with a bag of burgers from Checkers. And that’s what I wanted, because I always eat at Checkers and McDonald’s at McNeese [the state university Keith attended].”

Keith Frank might disagree, but I think his music has improved and matured over the years while his audience’s musical tastes have evolved as well. Get On, Boy! production sounds primitive, the accordion sounds tinny, and Keith hadn’t yet found that warm voice we have all come to love. In fact, most the tunes on that album were instrumentals. In the 90s zydeco artists were just beginning to experiment with R&B styling, and

the tempo of the songs was still about as fast Clifton Chenier and other zydeco pioneers played —170 to 200 beats per minute. “Going to McDonald’s” is 184 bpm, “Huh” is 183, and the title song is 172. In contrast, zydeco tunes on Keith Frank’s more recent albums average about “I hated zydeco, I hated the 154 bpm. So with a few more whole thing. My old man albums under his belt and the would make me practice, tempo slowed, rave reviews and I could always find began to pour in. something better to be In 2005, Dan Willging doing. Then as things reviewed Going to See Keith moved on, my dad started Frank for OffBeat Magazine. playing less and less. Then I realized it’s a part of my life, and I couldn’t stand being without it.” “Frank still remains the same breed of envelope-pusher he was when he helped reshape the old man’s game of zydeco. This latest 20-track bounty, mostly club staples only now etched to sonic medium, could be his most creative yet. As one pile-driving track slams into the next, touches of calypso, Meters and other familiar riffs spin

a fresh perspective when it was thought zydeco had seen it all. Surprises fly out of nowhere and from every angle, like Frank jamming on keys, laying down spaghetti western guitar riffs and even mustering a blues buster with wicked guitar lines and a harmonica howl. Also on tap is the Rockin’ Sidney tune debut of “Work That Coochie” that was intended, had he lived, to be on the latest platter with Soileau Zydeco Band as the backup squadron. Even with the unusual but welcomed nature of this beast, it’s still a true Frank record. Two songs are traditional, sung in Creole French; others like the title song and anything else with ‘Keith Frank’ emblazoned in the title work as bump-and-grind dance floor dandies. On the last few tracks, Frank gets radical once more — township blasts, country thrashing, flamenco flashing, and a jazzed jam with saxophonist Ricky Julien.”

According to Tisserand, some of the songs on Get On Boy! featured the same minor chord vamps and classic rock riffs used by another performer who lived just a few miles down Highway 165 from Soileau, and who had also gone to Lanor to make his debut record: Beau Jocque. By

this time, Beau Jocque and “Give Him Cornbread” had become the top draw on the local zydeco circuit.

It has to be said that a storied rivalry between Keith Frank and Beau Jocque highlighted the highly competitive nature of the music business, the question of originality in music, and the striving of artists who covet the spotlight to get their due. Since the dawn of recorded music, artists have complained ruefully of not getting the recognition and money they deserved. Boozoo Chavis stayed away Keith Frank in 2010 from recording music for nearly three decades after he was cheated, or so he maintained, of the proceeds from his popular hit hit, “Paper in My Shoe” recorded

in 1954. Boozoo’s comeback in the ’80s, inspired in part by news that another accordion player was impersonating him, made a huge impact on the genre.

“Keith saw where Beau Jocque was getting the attention of the young ones, and how he was going into that rap beat,” Lavergne believed. “I think he kind of copied Beau Jocque to some extent, because he changed his style completely after he left me.”

It wasn’t long before a feud began to develop between the two musicians. Frank said the dispute began when he was sitting in with Beau Jocque’s band on guitar and drums, and some sound equipment broke. Whatever the cause, the two found themselves locked in perhaps the most bitter rivalry in zydeco history.

Tisserand wrote, “They hurled gauntlets at each other from stages and over local radio shows. There were charges — and countercharges — that one performer was trying to stop a club or festival from booking the other. When the two would run into each other in public, they either kept their distance or looked like they might break into a fight. Stories of the feud were recounted over dinner tables throughout Louisiana, and promoters shook their heads in disgust, wondering why the two players didn’t

take advantage of the attention to stage joint appearances called zydeco battles. But this was no longer the friendly rivalry once seen between Beau Jocque and Boozoo Chavis.

According to Tisserand, the first major battle erupted over a song — or two songs. In 1993, Get On Boy! featured a bouncy tune called “Went Out Last Night,” also known as “Hamilton’s Club.” It was an immediate hit at the dances. Also in 1993, Beau Jocque recorded the song “Yesterday,” released the following year on his disc Pick Up on This! It was also a hit.

Tisserand wrote that many zydeco songs share rhythms and melodies, but “Yesterday” and “Went Out Last Night” were, without a doubt, the same song. On their respective albums, each performer was credited as songwriter. Then the two songs began competing with each other for the top position on local zydeco radio shows. The dispute brought up larger questions of originality in songwriting.

Tisserand observed that in zydeco, matters of ‘authenticity’ and ‘originality’ are often set aside in the immediacy of crowd response. Families may debate the origins of particular songs, but when contemporary musicians tap the deep vein of shared songs

Dancers at a Keith Frank 2019 gig

and styles, they establish continuity both in the current scene and between generations. Today’s greater emphasis on recorded music, however, raises issues involved not only with pride of authorship but with royalties. The current debate on originality

in zydeco parallels larger discussions in contemporary rap and hip-hop. The jury is still out, most observers believe.

“There’s no town hall meeting to discuss these things amongst the musicians, you know,” says Floyd Soileau, whose Maison de Soul distributed Frank’s records. “Now, if one of these

“It’s like cookies,” songs should suddenly make a explained Frank. “You got lot of money, then you’ll see the to take it out, and test if problems start.” it’s done yet. Now if I play Every musician has a tale it out, and another about outright song-rustling. musician takes it, well, it’s Other times, the original my fault, because I source or inspiration for a song shouldn’t play it out.” is harder to trace. “Sometimes, you sit down and you’re thinking about something, and then another guy is sitting four or five miles down the road, he’s thinking of the same thing,” says Jeffery Broussard. “You don’t know how it happens, but sometimes it happens. You sit down and you think you hear something out the window. Maybe you’re watching TV, and

somebody is watching the same thing. But the same idea keeps falling at the same time.”

Complicating matters is the collaborative spirit between musicians and dancers, which means that zydeco songs are rarely composed in isolation.

“It’s like cookies,” explained Frank. “You got to take it out, and test if it’s done yet. Now if I play it out, and another musician takes it, well, it’s my fault, because I shouldn’t play it out. I’ve played new stuff out and other people have played it before I recorded it, and that kind of got to me, but I shouldn’t have played it in the first place.”

The relatively small amounts of money at stake seemed to keep the matter from spilling into the courts, but pride and reputation are priceless commodities. Fans took sides over “Yesterday” and “Went Out Last Night.” The matter was finally resolved to nobody’s satisfaction: it was determined that both songs derived from “I Got Loaded,” a popular R&B song by Little Bob and the Lollipops.

On September 9, 1999, Beau Jocque played a two-set show at Rock ’n Bowl in New Orleans, and drove home to Kinder. The

next morning he died of an apparent heart attack at the height of his career. Beau Jocque’s passing helped to clear a path for Keith Frank to establish himself as the Zydeco Boss.

Michael Tisserand surveyed Keith Frank’s work over his first two decades as a recording artist. Keith Frank & the Soileau Zydeco Band’s 2009 release Loved. Feared. Respected. gives a good sense of Frank’s remarkable breadth, from a funky “Zydeco Sont Pas Sale” to the massive hit “Haterz,” a slinky zydeco-rap hybrid that paired Frank with Baton Rouge rapper Lil’ Boosie. Following the death of Beau Jocque, Frank became the undisputed top draw for south Louisiana dancers, and his inclusion of rap, hip-hop, classic R&B, and even novelty pop is evident in all his later recordings.

On the double-album Undisputed, Creole lyrics and traditional Cajun and zydeco tunes such as “Lanse De Prien Noir” and “Josephine Is Not My Wife,” are also evident.

Two exciting live recordings, recorded eight years apart at Slim’s Y-Ki-Ki, make it clear just why Frank keeps packing in the crowds.

Keith Frank and the Soileau Zydeco Band in 2014

Frank’s earliest recordings On the Bandstand (Lanor) and Get On Boy! (Zydeco Hound) aren’t as well produced as his later work, but they have their charms—especially Frank’s sister Jennifer’s introduction on “Going to McDonald’s” and her sweet vocals on “Going Back to Big Mamou,” both of which can be found on the Lanor recording.

Frank showcased his grittier, leaner sound on What’s His Name? (Maison de Soul) in songs such as “One Shot,” which is a blend of vitriolic lyrics and gritty accordion playing.

Of his other Maison de Soul discs, Only the Strong Survive is

his most consistent work, although Movin’ On Up introduced his television-generation take on the theme to The Jeffersons. Keith’s father, Preston Frank, can be heard on Let’s Dance (Lanor) and the recommended Zydeco Volume Two (Arhoolie).

Dan Willging reviewed Follow the Leader / Boot Up in 2012 for OffBeat Magazine. Similar to 2007’s Undisputed—a double disc set with each disc featuring its own concept — Follow the Leader and Boot Up are also two distinct concept discs sold together as a set or separately depending on the demographic of the gig at hand.

For longtime zydeco zealots, Boot Up is a great place to start since it traces Frank’s roots evolution to its current day manifestation that’s prevalent on the more contemporary Follow the Leader.

“Lessons from the Master Boozoo Chavis,” a live segment from Boozoo urging the younger generation to keep zydeco alive, frames the quintessential concept of Boot Up: being rooted in your music and culture. Though not sequenced as such, “On the Bandstand” is the next logical stop since it shows where the

auspicious upstart was artistically in 1991 with a simplistic song structure that seems so primitive now.

A few tracks, like “Johnny Can’t Dance,” underscore Frank’s traditional side, but even they have their own signature twists and turns. The Creole French-sung “Adam 3-Step” features the accordionist playing quick, infectious syncopated riffs over

“Whether he’s playing in a tight, interlocking rhythm the tradition or using section. contemporary urban Yet Boot Up is not solely an influences, Frank never allegiance to tradition. It has loses sight of who he is and plenty of progressive moments. where he came from.” The instrumental title track — DAN WILLGING is one such example. Frank trading licks with guitarist Lucien Hayes sounds something like the Meters jamming on zydeco back in the day. Whether he’s playing in the tradition or using contemporary urban influences, Frank never loses sight of who he is and where he came from. On “Still Zydeco For Me,” he drops a fairly heady message: “if you take away the zydeco, it’s

Keith Frank and the Soileau Zydeco Band in 2019

our culture that pays the cost,” referring to those who infuse their music so heavily with outside influences that the zydeco core becomes practically invisible.

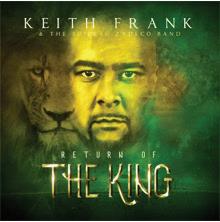

My favorite of all Keith

It’s not all heavy, but the Frank’s albums, Return of the King, was reviewed by Dan movie poster cover art and Willging for OffBeat Magazinedisc title could cause some in May 2018. Dan wrote that bewilderment, leading after two consecutive live some to believe Frank is albums, Keith Frank delivered laying a quick claim deed to his first studio release in six the Kingdom of Zydeco. years — a dense 20-track,

Rest assured, he’s not, 76-minute affair that’s his asserted Willging. most provocative yet. While there are the familiar love and sex themes, Frank isn’t afraid to address harder-hitting issues like depression, rape, suicide and distraught, single mothers resorting to prostitution (“Angelina,” “You’ll Never Be the Man Your Momma Was.”)

It’s not all heavy, but the movie poster cover art and disc title

could cause some bewilderment, leading some to believe Frank is laying a quick claim deed to the Kingdom of Zydeco. Rest assured, he was not, asserted Willging. He was just acknowledging his higher power. Rather for Frank’s 30th-something album, it’s all about balance, never staying with a particular theme or style for long. You can see where he came from on the ’90s-styled “On the Rise Again,” but nearly everything else reveals how far he’s evolved. There’s sansaccordion Southern soul (“It Ain’t What You Got,” “She’s Gifted”) but perhaps the most creatively engineered track is “Don’t Believe the Hype.” It opens with turntable scratches and a sampled, unidentified male vocalist wailing in Hebrew before Frank injects a trunk-rattling funky thrust with rapper Nathan “Pole” Brown.

But if you are looking for a clue regarding Frank’s artistic blueprint, the breezy “It’s Okay to Be Different” sums it up perfectly: “It’s okay to be a little different/ It’s okay to have your own name.” Simple but meaningful, and to think Keith Frank imparts messages like that with killer dance grooves.