13 minute read

Giant: Beau Jocque

IMAGE USED WITH PERMISSION OF PHOTOGRAPHER RICK OLIVIER

GIANT

Advertisement

Beau Jocque

An abridged version of the Beau Jocque story in Update! #95

Scott Billington joined Rounder Records in the 1970s and learned the ropes of the record label business working the sales, promotion and art departments. Billington worked with a variety of artists in the blues, Cajun, jazz and zydeco genres. In 1981, Billington’s production work of bluesman Clarence ‘Gatemouth’ Brown won Rounder its first Grammy award, and with later Rounder projects he ‘rounded up’ another Grammy award and eleven nominations. As a graphic designer and art director, Billington created hundreds of album covers for Rounder and other labels. And as a harmonica player, Billington recorded with Boozoo Chavis, Sleepy LaBeef, and Irma Thomas, and toured with Nathan Williams and the Zydeco Cha Chas. Billington worked with Beau Jocque on his recordings with Rounder Records. Now he is also on the faculty of Loyola Univeristy in the Film and Music Industry Studies department. His resume is quite impressive.

Billington wrote in his story, “Beau Jocque: The Funkiest Band in the Land,” that he first heard Beau Jocque in 1992 at the Quarterback Lounge in a rundown neighborhood of Lafayette. “I

felt as if I had been transported to a primeval moment in which all the music I loved — funk, blues, R&B and zydeco — had coalesced into a single, relentless groove. I was also a little bit scared. Here was man with a “You’d better get down here and record Beau Jocque because he’s hot as a firecracker.” linebacker’s build, leering into the dark club and singing with a gruff-voiced intensity that could only be compared to Howlin’ Wolf or James Brown, goading his band — KERMON RICHARD mates to shout back at him. As the energy of his performance intensified, the double bellows of his small diatonic accordion, which looked like a toy in his large hands, seemed in danger of being ripped to pieces.”

Beau Jocque’s onstage persona was a dramatic contrast to the measured and soft-spoken man he had met on the phone a few weeks before. The late Kermon Richard, the owner of Richard’s Club in rural Lawtell, Louisiana, had introduced them. “You’d better get down here and record Beau Jocque,” he said, “because he’s hot as a firecracker.” Beau Jocque was packing the club with eager young Creole dancers who were often new to zydeco.

Billington remembered, “By the time we made his first album for Rounder Records, he had found the musicians who would help him realize his vision. His bass player, Chuck Bush, followed his moves with a manic focus, carving out a fluid melodic counterpoint, while his Beau Jocque’s producer drummer, Steve Charlot, stuck straight to Scott Billington the point, hammering out an unrelenting, ‘double-kicked’ zydeco beat while yammering a constant patter of high-pitched vocal asides. With guitar player Ray Johnson and rubboard player Wilfred Pierre in tow, the band never wasted a note on anything that did not contribute to the groove.

“We rehearsed for the album at Richard’s Club. The next day, my small rental car was barreling along US Highway 190 at 80 miles an hour, on the two-lane bridge that crosses the Atchafalaya Basin. Chuck rode with me, and we were trying to keep up with Beau Jocque. A few months earlier, I had been cited for going 57 miles per hour on the same road. I gave the policeman my Louisiana Colonel card, which had been bestowed

on me by Governor Edwin Edwards for my work in recording Louisiana music, and which I had been told might save me from a ticket, but it made little impression. Now, rocketing along behind Beau Jocque’s trailer and diesel pickup, we seemed to have true immunity from the speed traps. “At Ultrasonic Studio in New

“Once we began rolling Orleans, our recording engineer, tape, [recording engineer David Farrell had already set

David Farrell] turned to up microphones by the time we me and said, ‘I’ve never arrived. Once we began rolling heard zydeco that tape, he turned to me and said, sounds like this.’” ‘I’ve never heard zydeco that sounds like this.’ He was right, for Beau Jocque and his mates, especially Chuck Bush, had the ability to improvise grooves and motifs that sent zydeco music to a more freewheeling and funky place than it had been before, and they didn’t choke in the studio. We did a few vocal and percussion overdubs, for I wanted the band to shout back in the same way they had at the Quarterback Lounge, and in eight hours, the record was done.”

Zydeco musicians of the 1990s followed one of two traditions: the older, percussive style of Boozoo Chavis, who uses a button-key accordion, or the more rhythmand-blues-influenced style of Clifton Chenier, who employed a piano-key accordion. Beau Jocque was of the Chavis tradition, but he updated it by incorporating stuttering hip-hop beats and riffs from the funk band War and the Texas blues-rock trio ZZ Top.

“It’s not a stretch of the truth to say that Beau Jocque invented the contemporary zydeco sound,” posts Floyd’s Record Shop’s website. “He was not only the most popular zydeco star in Louisiana and Texas in the 1990s, but an unmistakable voice whose presence and no-holds-barred energy won him fans around the world.”

Beau Jocque’s gruff vocals, fusion of rock with zydeco, and the powerful rhythm and heavy bass sound of the Hi-Rollers backing him was unmistakable. Also unmistakable was his size. At six-foot six inches tall and weighing 270 pounds, Beau Jocque, whose stage name translates as ‘really big guy’ in Cajun patois,

seemed to do everything in a big way. When he began to tour the local clubs, his steamrolling accordion riffs and deep, growling vocals quickly became a huge draw. In 1993 Beau Jocque began playing Mid-City Lanes Rock’n’Bowl in New Orleans. Club owner John Blancher recalled in the New Orleans Times-Picayune that “I put support beams underneath the dance floor for Beau Jocque. People danced harder when he played. It was almost hypnotic. He just grabbed dancers.”

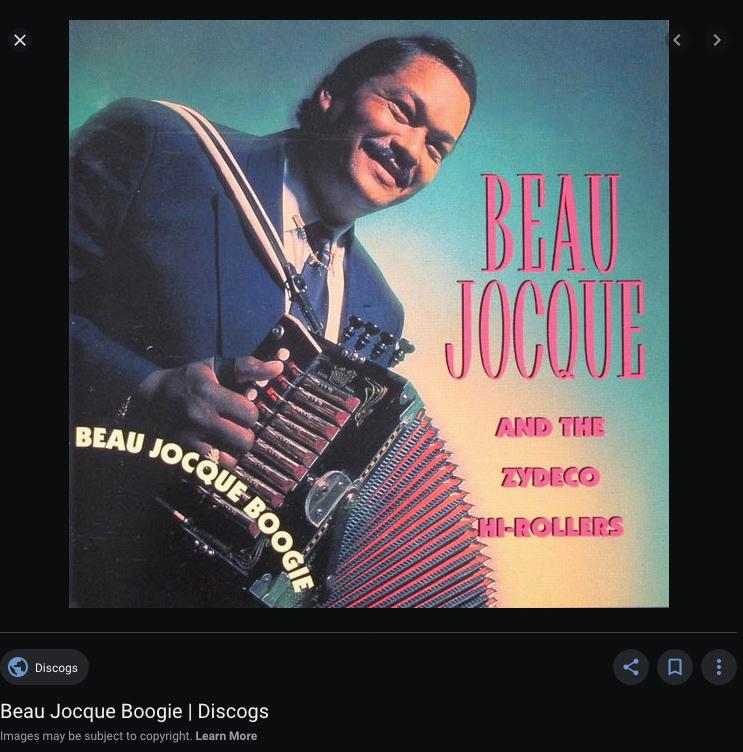

Beau Jocque’s 1993 debut for Rounder Records, Beau Jocque Boogie, is considered a classic of the genre. It features “Give Him Cornbread,” the band’s signature song that infused traditional two-step zydeco with hip-hop and funk. Beau Jocque Boogie garnered immediate acclaim and became the best-selling zydeco record ever. Beau Jocque included a mix of his own originals that included “Richard’s Club” and “Beau Jocque Boogie,” along

with his own arrangements of traditional Creole songs. He quickly followed up Boogie with Rounder’s Pick Up on This! Called a “first-rate party album” by All Music Guide reviewer Thom Owens, the album cemented Jocque and the Zydeco HiRollers as THE zydeco band. Radio stations were flooded with requests to play the album, and audiences would pelt Beau Jocque with cornbread when he performed “Give Him

Cornbread” at festivals.

“When that record hit, you couldn’t go anywhere in southwest Louisiana without hearing it coming out of somebody’s window or car,” Billington said. “It was the kind of record they played twice in a row on the radio. When he played Richard’s Club, there would be cars up and down the highway for a half mile in either direction.”

“When people would ask him about his influences, he’d be just as quick to say Carlos Santana or War as he would Boozoo Chavis or Clifton Chenier,” Billington said. “Seventies funk was just as much a part of his sound as the traditional zydeco sound.”

The popularity of Beau Jocque and the Zydeco Hi-Rollers soared. Beau Jocque was filling Richard’s Club in Lawtell, Hamilton’s Club in Lafayette, and other zydeco halls with hundreds of dancers, many of whom had previously dismissed zydeco as the music of their parents and grandparents. “He brought younger people to the dance hall, and helped make the tradition relevant for the next generation,” said Michael Tisserand.

Michael Tisserand, author of The Kingdom of Zydeco, recalled writing about Beau Jocque: “The problem was size. When writing about Beau Jocque, describing his enormity was the main challenge. He ‘straddles center stage like a Colossus, spreading his long legs so his 6-foot-6 frame can fit under Richard’s Club’s low ceiling,’ I

attempted in the 1993 liner notes to Beau Jocque Boogie, the first of Beau Jocque’s five albums for Rounder. ‘He bellows in the kind of voice you might find at the top of a beanstalk,’ went a later effort. Beau Jocque was big. Once, on a drive in south Louisiana, he stopped to look for a leather jacket. Most of what was on the rack barely fit around his arm. Another time, I joined him in Canal Place, looking for shoes. We visited store after store until finally finding a single pair that fit.” “On stage, the accordion “On stage, the accordion seemed like a tiny sponge in his massive hands.” seemed like a tiny sponge in his massive hands. When he opened his mouth to sing, he evoked the equally sizable Howlin’ Wolf as a blues influence, and he married his vocal style with rap, funk and classic rock styles from War and ZZ Top, achieving a big sound with loud volume and long solos that led to exhausting dances.”

Starting in the early 90s, his impact in south Louisiana eclipsed everything that had come before. Trucks parked for miles up and down the highway outside Richard’s Club. Hamilton’s Place in Lafayette had to move the cows from a

nearby field to make more room for cars. “Give Him Cornbread” was everywhere. People used to drive past his house in Kinder, car windows open, radio blaring, bass thumping, “Cornbread” screaming.

“Beau Jocque never truly made it big in the world of popular music,” Tisserand went on, “but he did appear on David Letterman’s and Conan O’Brien’s shows, and his records outsold most zydeco releases. These indicators of success, however, seem like small change now, as does the fact that I have never experienced music and dancing like I did with Beau Jocque’s music, and that if I wanted to turn someone on to zydeco, I always just gave them Beau Jocque Boogie and it blew their minds.”

When the Rolling Stones were in New Orleans to perform in October 1994, Mick Jagger and Charlie Watts made it a point to catch Jocque’s show at the Mid-City Lanes. After the show, Rock’n’Bowl owner John Blancher said to Beau Jocque, “Can you believe Mick Jagger and Charlie Watts came to see you play?”

Blancher recalled Jocque’s unfazed, unimpressed response: “Yeah, I saw them,” he growled. “That’s why I turned my back —

so they wouldn’t steal my licks.”

Beau Jocque was born Andrus Espre on November 1, 1953 in Duralde, Louisiana to Sandrus and Vernice Espre. Growing up, Andrus learned Louisiana Creole French and spoke it fluently. His father (nicknamed “Tee Toe”) was a well-respected accordion player who performed at local dances, but he gave up playing to raise a family. Andrus played guitar in a high school band, and his influences were blues, rock and funk bands like War, ZZ Top, Stevie Ray Vaughan, James Brown, Sly and the Family Stone, and Santana. Andrus Espre picked up music quickly, and in high school Warren Ceaser, who went on to play with Clifton Chenier, nicknamed him “Juke Jake” for the way he could learn new songs. Beau and Ceaser played together in an R&B combo that was an offshoot of their high school band where Beau played tuba.

Espre enlisted in the Air Force after high school, and eventually made it to the rank of sergeant, had a top security clearance and was stationed in London and Germany. He once

escorted Henry Kissinger around Europe. Espre had his first near-death experience while in the Air Force when an explosion left him in the hospital with amnesia. He spent nine years in the Air Force, and then left the military to work as an electrician and welder.

By the time he reached the age of 29, with a wife, two sons, and a decent job as a licensed electrician, Espre’s life seemed to be set. While doing electrical work in an oil refinery, Espre experienced a work-related fall in 1987 that left him temporarily paralyzed from the waist down. During his recuperation, as part of his therapy, he began playing his father’s button accordion. After a year of practice and gaining proficiency on the accordion, Espre and his wife Michelle began to study the styles of the successful bands on the zydeco circuit.

“Accidents have played a big part of my life,” he said, and then he unexpectedly laughed. “And me getting into zydeco — that was an accident.”

“We checked out C.J. Chenier, Buckwheat Zydeco, Boozoo Chavis, John Delafose, and I'd watch the crowd. When they got

real excited, I’d try to feel what was happening at that point. Was it the rhythm guitar? The drums? The accordion style? I realized that when you get the whole thing just right, it’s going to move the crowd.”

Influenced by rock, soul and blues, Espre assembled a band in 1991 with brawny bass lines and brash rock lead guitar solos. His wife Shelly played rubboard. He hand-picked a band that included mostly younger musicians, calling them the Zydeco Hi-Rollers. They initially talked themselves into a few gigs in small clubs or for trail ride parties, and word spread quickly about a new zydeco artist. He appealed to a younger crowd by incorporating rock guitar solos, blues-rock beats, and rap lines into his songs, along with his bass vocals and growling lyrics. To get airplay on the local radio stations, Espre would need a recording. In 1991, he made a deal with Lee Lavergne of Lanor Records to produce a cassette album, My Name is Beau Jocque. (This was about the same time that Keith Frank made his first album on cassette with Lanor called On The Bandstand.)

When radio stations began to play My Name is Beau Jocque, the larger zydeco clubs began to take notice. Within a short amount

of time, Beau Jocque was playing clubs four to five nights a week and was becoming one of the biggest draws on the Louisiana zydeco circuit. In June 1995 one newspaper stated that “There has simply never been a zydeco phenomenon like Beau Jocque and the Hi-Rollers who have thoroughly modernized zydeco.” Andrus Espre had reinvented himself as Beau Jocque. Scott Billington marveled that it was as if he had devised a fictitious character and now was completely inhabiting him.

Followup Rounder releases like Pick Up On This, Git It, Beau Jocque!, Gonna Take You Downtown, and Check It Out, Lock It In, Crank It Up, were consumed by zydeco fans and even attracted listeners who previously hadn’t listened zydeco before. By the mid-1990s, Beau Jocque was the most popular artist in the zydeco genre. Unlike other artists like Nathan Williams, Buckwheat Zydeco and C. J. Chenier, Beau Jocque wasn’t interested in playing festivals in New Hampshire or clubs in Sacramento. Instead he chose to rule the Texas/Louisiana zydeco circuit. Even if he wasn’t the ‘king,’ he was certainly the boss.

Beau Jocque’s popularity brought with it financial gain,

allowing him to indulge in acquiring a collection of high performance vehicles. Not only did he purchase a flashy Corvette and a luxurious tour bus, the customized metallic green Ford Centurion super extended cab pickup truck that hauled his matching instrument trailer, accented with neon trimmed chrome running boards, let “To me, Beau Jocque was the genius of the genre.” — ROCK’N’BOWL OWNER everyone know Beau Jocque had arrived. During the New Orleans Jazz & JOHN BLANCHER Heritage Festival, Mid-City Lanes hosted an annual battle of the bands — ‘Boo versus Beau’ — pairing Boozoo Chavis and Beau Jocque. The event always drew well over 1,000 patrons including many who were not typical zydeco fans.

“He definitely introduced new people to zydeco,” John Blancher said. “To me, Beau Jocque was the genius of the genre. As long as I’ve been around, he had the most impact on the music, with more musicians copying his songs and trying to do his stuff.”