Testing times

‘It was very easy to get through the larval stages but you couldn’t get the things to eat anything but live food. It was a huge impasse, a lot of work went into that but it never really got anywhere.’ Turbot, however, grew fast and Alderson was dispatched to the North Sea, where, along with Alan Jones, he collected ‘loads of turbot eggs from a spawning female’. ‘We played around with the standard rearing method in clean water, feeding them with tiny rotifers. They ate those fine but then they just trickled away and died.’ They had a limited amount of algae for growing the rotifers but he noticed that some ponds at the university station had an algal bloom in them. The breakthrough came when Alderson tried introducing some spare larvae into tanks containing rotifers along with water from the pond. From that they got 50 juvenile turbot. His success, he believed, was down to the presence of the algae with the rotifers. ‘That was the key because the technique for plaice and Dover sole had always been clean water through the tanks. This was a different approach. The next year we set up some big tanks and fed algae into them with powerful lights over the top so the algae would reproduce.’ They produced 1,000 juvenile turbot that year, 1973, and by experimenting with different algae eventually began consistent production of juvenile fish. Alderson said he had a lot of freedom to follow his own lines of enquiry and being stuck out on an island helped, though he was in touch with others doing the same thing. ‘There was a network of people all involved in the development of fish cultivation and mostly they were talking to each other. We had visits of

www.fishfarmer-magazine.com

Dick Alderson.indd 53

scientists from France, Portugal and the Soviet Union who were all interested in trying to raise turbot, as well as commercial companies who were hoping to develop a profitable process. ‘People like British Oxygen were looking at feeding oxygen into recirculation systems so you could economise on the water and heat. ‘Golden Sea Produce were doing the work at the power station. And the Unilever people from Aberdeen were interested in what we were doing and would come from time to time to Port Erin. They had identified what they called ‘the fish gap’ and were looking at a number of marine species.’ Alderson was delighted for the team at Port Erin when they were able to try Marine Harvest’s smoked salmon, sent over in return for some plaice he supplied for a Unilever exhibition. And when MAFF pulled the plug on the Port Erin turbot operation in 1977, it was Unilever that gave Alderson his next job. But instead of going to Unilever Research in Aberdeen, he was sent to Lochailort to run the research unit there and, while continuing with flatfish work, was also introduced to what they were doing with salmon. ‘It was still the early days and facilities at Lochailort were pretty basic. But because the

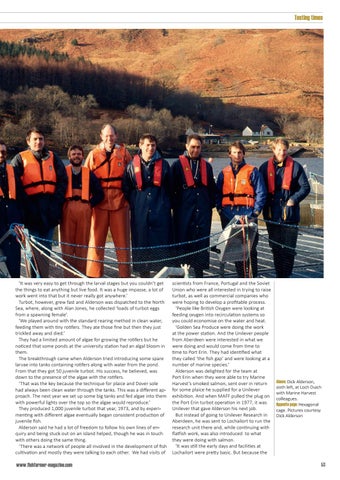

Above: Dick Alderson, sixth left, at Loch Duich with Marine Harvest colleagues. Opposite page: Hexagonal cage. Pictures courtesy Dick Alderson

53

04/10/2017 16:58:38