Latest episodes:

Mind the gap: Do super tax changes mean anything for women?

Super shakeup

Material change

Latest episodes:

Mind the gap: Do super tax changes mean anything for women?

Super shakeup

Material change

Three years after it first announced plans for a superannuation offering, Vanguard is now home to one of the cheapest MySuper products.

Mercer analysis of publicly available retirement income strategy summaries shows a great disparity between super funds’ approaches.

SUPER

Cbus chair Wayne Swan has warned the industry has a fight on its hands when it comes to big structural reforms moving forward.

AUSTRALIANSUPER ENTERS TOP 20 PENSION FUNDS

The super giant has risen two places and now ranks number 20.

PERFORMANCE TEST PAUSE IN MEMBERS’ BEST INTERESTS

9

10

12

Chant West has welcomed the proposed pause in the Your Future, Your Super performance test, saying it’s in the best interest of super fund members.

Associate Editor Andrew McKean andrew.mckean@financialstandard.com.au

Design & Production

Shauna Milani shauna.milani@financialstandard.com.au

Technical Services

Roger Marshman roger.marshman@rainmaker.com.au

Ian Newbert ian.newbert@rainmaker.com.au

Fiona Brillantes fiona.brillantes@rainmaker.com.au

Advertising

Stephanie Antonis stephanie.antonis@financialstandard.com.au

Director of Media & Publishing

Michelle Baltazar michelle.baltazar@financialstandard.com.au

Director of Research & Compliance

Alex Dunnin alex.dunnin@financialstandard.com.au

Managing Director Christopher Page christopher.page@financialstandard.com.au

All editorial is copyright and may not be reproduced without consent. Opinions expressed in FS Super are not necessarily those of Financial Standard or Rainmaker Information. Financial Standard is a Rainmaker Information company.

57 604 552 874

This CPD-accredited forum will explore how considering people, planet and profit can impact investment performance. ESG and ethical investing have never mattered more to advisers, institutional investors, retail investors as well as super fund members, and regulatory scrutiny on this space has never been more intense.

We will explore the nuances of ESG investing, the state of the market, products on offer and how ESG screened portfolios can be used to gain performance benefits. Hear a dynamic mixture of speaker presentations, panel discussions and case studies to help explore the evolving world of ESG investing.

Tuesday, 23 May 2023 | 8:30am to 2:30pm

Sydney | In-person & virtual

24

31

Investment

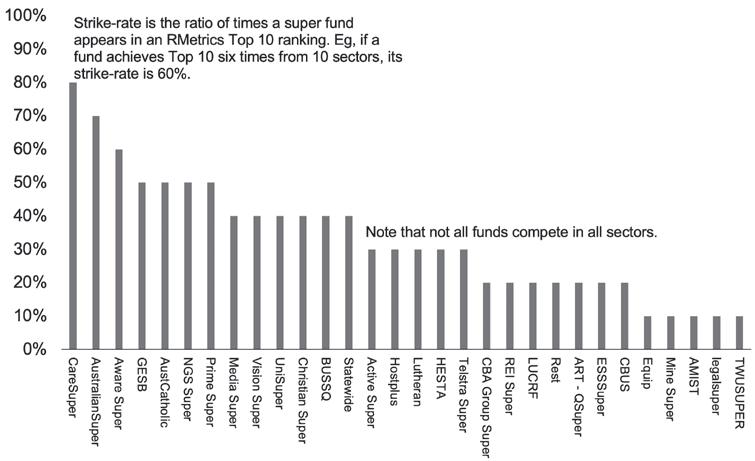

ASSESSING WORKPLACE SUPER FUND PERFORMANCE

By Rainmaker Information

This paper explains the development of the RMetrics assessment model as a means of capturing multiple measures of risk-adjusted return for a product and integrating them into a single holistic risk score.

Investment INVESTING TREATIES IN CONFLICT ZONES

By Nastasja Suhadolnik, Cara North, Caitlyn Georgeson, Madelyn Attwood, Corrs

Chambers Westgarth

The nature and importance of bilateral investment treaties in terms of the protections they offer to individual and corporate entities when investing in territories other than their state of nationality.

36

Compliance BUILDING A SUSTAINABLE SYSTEM TO MANAGE REGULATORY CHANGE

By Richard Batten, Donna Worthington, Ian Lockhart, Michael Lawson, MinterEllison

To assist Australian financial services businesses with managing regulatory change, this paper offers a framework that can be applied to build a sustainable approach to change.

42

Ethics & Governance GREENWASHING: TAKING A PEEK BEHIND THE GREEN SCREEN

By Jonathan Steffanoni & Jessica Pomeroy, QMV Legal Trustees are under increasing pressure to ensure that in promoting the green credentials of their investment products they provide a clear and accurate representation of the funds’ ESG-related investment practices, goals and targets in all communications with potential investors.

56

48

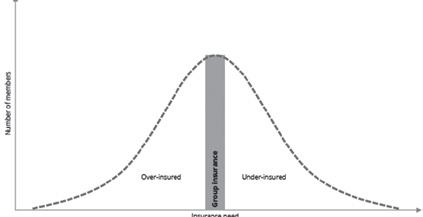

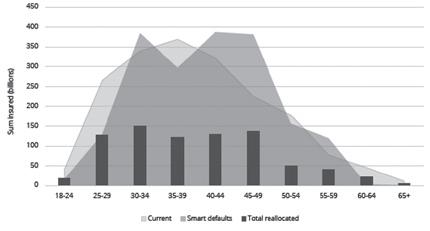

Insurance USING DATA TO BETTER TARGET INSURANCE BENEFITS WITH SUPER

By John O’Mahony and Ben Lodewijks, Deloitte

This paper investigates how better collection, access to and analysis of member data can lead to the better alignment of default life, TPD and IP insurance policies offered to superannuation members.

SMSFs

WHEN DO TRUSTEES NEED MINUTES AND RESOLUTIONS

By Phillip La Greca, SuperConcepts

What, when and how to document key decision-making processes and their outcomes is a critical issue for all trustees, including SMSF trustees.

51

SMSFs

THE GUIDE TO PAYING SUPERANNUATOI DEATH BENEFITS

By Graeme Colley, SuperConcepts

This paper provides a checklist of practical, ordered steps for SMSF trustees to follow to help them meet the deceased member’s wishes while also complying with superannuation law and ensuring that the ongoing trustee structure remains compliant.

59 Ethics & Governance TRUSTEE GOVERNANCE AND ACCOUNTABILITY

By Lisa Butler Beatty, Zein El Hassan, Lisa Rava, My Linh

Pham, KPMG AustraliaThis paper looks at the ramifications for superannuation fund trustees of recent and proposed legislative reforms.

Every middle-class white-collar services sector employee has by now heard of the 'generative artificial intelligence' website ChatGPT. Whether it's coming for your job depends on the value you add doing whatever it is you do.

ChatGPT exploded into the mainstream mid-January this year and within weeks had stirred up a frenzy. In a rendition of the reaction when calculators first went mainstream in Australia, or new laws in Florida banning all books in schools, hundreds of schools and universities quickly announced they would ban it. Trouble for them is that it’s generative content so plagiarism checkers will be useless against it.

This is what happens with every new technology leap: the establishment panics. The same occurred when internet search engines exploded onto our computer desktops and when smartphones were unleashed. But few of us probably expected the greatest disruptor of all, Google, would themselves announce they will block all AI-generated content and not include it in search results.

Many of us may be thinking that friendly, easy to use AI has just crept up on us. Not technology insiders, they've been watching these developments gather pace over the past few years under cover of the pandemic. Which might be why these same insiders are telling us that this is just the beginning.

There are two ways to respond this. One, if you're a services sector professional who gets paid a lot of money to in essence just rehash other people's work, you'd be wise to start updating your resume. I hear the Australian Defence Force is desperately looking for recruits and Australia has a chronic shortage of skilled trades people.

Two, reimagine. AI is one of the most exciting technological breakthroughs in decades that will transform many sectors of the global economy. We're just not sure how. Better to be part of the change than fall victim to it.

We also need to remember that ChatGPT is just a prototype and has many weaknesses and limitations that even its developer, the OpenAI corporation, is warning

us about. But I can already see some useful test case generative AI applications that could fix a few long-standing problems in how the superannuation industry operates.

Like how superannuation is bogged down with blackletter-law compliance, legislative complexity and administrative intensity with vast armies of experts paid big salaries to explain it all to the rest of us.

Play our cards right and within a few years many of those compliance, legislative and pension entitlement experts who spend most of the lives keeping up with technical details, and the thousands analysts working for active investment managers only to be gazumped by the market index each year, might be able to recraft their roles and get back to actually adding value to their employer's clients' lives.

Super fund trustees are meanwhile crying out for scalable financial advice services to help explain to their millions of fund members in or approaching retirement how to best use their super fund. These trustees might now have their solution. The dwindling number of human financial advisers, rather than be threatened by this, would surely welcome the support of generative AI to simultaneously improve service quality and slash costs to fund members.

There's a lot of water to flow under the bridge before these AI efficiencies began to happen in the superannuation sector. But one thing we can count on is that generative AI and how to either harness, regulate or tame it will be 2023's defining issue for corporate Australia. Doubly so for a services sector like the superannuation industry. fs

The quote

I can already see some useful test case generative AI applications that could fix a few long-standing problems in how the superannuation industry operates.

Alex Dunnin executive director, research & compliance Rainmaker InformationAustralian Retirement Trust has appointed State Street as its custodian and administrator.

The $175 billion superannuation fund has confirmed the mandate, chief financial officer Anthony Rose commenting: “After a comprehensive and thorough tender process, Australian Retirement Trust has chosen State Street as our preferred and primary custodian and investment administrator.”

While the fund didn’t confirm when the appointment was effective, a document on the fund’s website last updated May 18 lists State Street as the service provider.

Northern Trust was QSuper’s custodian and was retained in the merger with Sunsuper last year. Interestingly, Northern Trust replaced State Street as QSuper’s custodian in 2018, taking over the mandate State Street had held since 2012.

According to the Australian Custodial Services Association, as at June end, State Street ranked as the fourth largest custodian in Australia with $625.4 billion; Northern Trust ranked second at $679.3 billion.

Meanwhile, following a review, State Street will also continue to provide custodial services for Rest. The mandate includes back office and custody services, accounting, unit pricing, performance, and analytics. fs

Stockspot’s Fat Cat Funds Report has named and shamed the worst performing superannuation funds in Australia, all of which are retail offerings.

OnePath was named the overall worst performer, followed by Colonial First State, AMP, and ClearView.

Meanwhile, Qantas Super was named the best overall performer, followed by UniSuper, HESTA, AustralianSuper, and IOOF.

This year's report compared more than 500 multi-asset investment options offered by Australia’s largest 90 super funds. The funds were assessed on how they performed after fees and compared to other super investment options of similar risk over five years. The data further analysed the success of funds based on investment strategy.

It found the top performing balanced funds based on a five-year return to be Qantas Super - Balanced at 6.10% pa, Qantas Super - Glidepath: Destination at 6.10% pa, and AustralianSuper - Conservative Balanced with 5.51% pa.

The worst balanced options were Zurich - Capital Stable with 0.59% pa, OnePath - OptiMix Conservative on

Chloe Walker

Commonwealth Superannuation Corporation (CSC) selected Iress as its new technology partner in a bid to improve member outcomes, reduce administration complexity and drive down the cost to serve through a digital-first approach.

On an initial five-year contract, Iress will provide the super fund with its registry software, Acurity, for the administration of its defined benefit scheme members.

The registry software will deliver the consolidation of legacy and disparate systems, migrate all products on a single registry and enhance access to data.

The migration of members to Iress’ unified registry and operating model will be managed in stages over a three-year period with the first expected to be completed by July next year.

1.13% pa, and ClearView - IPS Active Dynamic 50 at 2.05% pa.

Other top performers included Qantas Super – Conservative for best moderate fund while TAL Personal Super’s Capital Protected option was the worst. Qantas Super – Growth was best growth option and Zurich – Balanced was the worst. MLC Horizon 7 Accelerated Growth Portfolio was the best performing aggressive growth option while OnePath OptiMix Balanced was the worst.

The report also found that prominent funds investing in unlisted assets claimed to be less impacted by market volatility, due to a long-term strategy.

Despite some fund crediting their exposure to unlisted assets with positive performance last year, the report highlighted there are zero disclosure obligations around these assets.

The second major trend coming out of the report for this year is that scale does not necessarily lead to better outcomes for members.

“We found no evidence that larger funds outperform smaller funds. The performance of merged funds has not improved," it explained. fs

The financial impact of this new contract does not impact 2022 guidance.

CSC’s chief executive officer Damian Hill said: “We’re committed to putting customers first, and this is another important step in a significant transformation program aimed at improving member outcomes and operational efficiency.”

“We selected Iress due to its deep industry and technology expertise, as well as the strength and ability of its software capabilities to deliver on our goals.”

Iress chief executive Andrew Walsh said: “We’re pleased to be selected by CSC to support its vision of reducing cost, minimising risk and eliminating the need for manual and paper-based workflows."

Walsh added that the announcement highlights the demand to adopt a target operating model underpinned by digitisation and automation- regardless of fund size. fs

The quote

We found no evidence that larger funds outperform smaller funds.

Andrew

McKeanAppearing before the House of Representatives’ Economics Committee, APRA’s Margaret Cole said the regulator is concerned about some of the super funds that passed the performance test yet fail the regulator’s own sustainability testing.

In March 2022, APRA released a report that showed 24 smaller super funds face immediate sustainability issues, while more than half of those with between $10 billion and $50 billion in funds also face adversity. This is based on number of member accounts, cash flows and rollovers.

Some of the funds that passed the performance test this year, by APRA’s observations and calculations, don’t look to have a long-term sustainable future, Cole said, saying this is perhaps one of the regulator’s biggest concerns.

“We will continue, even where there aren’t fails to nudge some of those funds that we see probably don’t have sustainability, to consider their options for the future and how their members can be better served,” she told the committee.

The comments followed questioning by independent MP Allegra Spender over whether recent reforms in the sector are driving an excess of consolidation.

Cole acknowledged the industry has experienced significant consolidation in the last two years, driven by the performance test. However, a very large number of trustees remain in the industry, she said.

“We had over 212 in 2013, we’re down to 160 in 2021. It’s still a large number,” Cole said. fs

Three years after it first announced plans for a superannuation offering, Vanguard is now home to one of the cheapest MySuper products - a lifecycle solution that auto-adjusts 36 times.

it the cheapest in market for a $50,000 balance - but only just. ANZ Staff Super has fees of 0.588%.

But it will get cheaper, Lovett told Financial Standard

We've

It was back in November 2019 that Vanguard's Robin Bowerman revealed the indexer's plans to re-enter the super sector. Later that month, Michael Lovett was appointed as head of superannuation, tasked with leading the development and launch.

Three years later, Vanguard has unveiled Vanguard Super SaveSmart, a lifecycle MySuper product and series of index-based diversified options and single sector options.

The product has 36 cohorts, with the allocation to growth assets set to begin reducing when a member celebrates their 47th birthday. A typical lifecycle product adjusts allocations four or five times.

A key selling point of the product is its low-cost, including no dollar-based fees. The lifecycle option comes in at 0.58% total fees per annum which, according to Rainmaker analysis, makes

“We’ve never set ourselves to be the lowest cost in every category, we are a low-cost provider, but I think the difference with us is that we're lower cost in time,” he said.

“So, the more success we have, the lower our fees will drop. What we have now, we think is competitive, but it is going to be lower in five years’ time with success; we’ve been in Australia 25 years, and we’ve dropped our prices 40 times, so we've got that history of doing it.”

As of 10 November 2022, about 18,000 potential members had expressed interest in taking up the product, in addition to several financial advice firms that will be able to access it through the Vanguard Adviser Portal, to be rolled out in the coming months.

“Not all of those will follow through, we know that. But we think a good number will, so we're really excited by Lovett said. fs

A survey of superannuation fund members found overall satisfaction has declined and more are considering changing funds.

The latest CSBA FEAL Superannuation CX benchmarking report surveyed close to 5500 members from 20 super funds and found that customer experience has declined across all key measures.

The survey found overall satisfaction has dropped to 7.7 from 8.1, while the ease of dealing with a fund dropped 8.3 to 8.0, and the likelihood of switching grew from 17% to 23%.

Of those that had recently interacted with their super fund, 25% said they’d considered switching in the last 12 months and 63% of them said they’re likely to do so in the next 12 months.

Broken down, it’s those aged 35-44 that are most

likely to switch, with 30% saying they’d likely do so in the coming year. Those aged 25-34 are also high risk at 26%.

When questioned on whether they feel empowered to retire or in retirement, only 59% of those aged over 55 said they had a high degree of confidence they’d have enough money to be comfortable. Further, 33% said their fund didn’t empower them to plan and prepare for retirement; last year one in four said the same.

Overall, the Net Promoter Score for all funds dropped 11 points to +15.

CSBA CX director of finance Sam Monteath said that while it was no surprise to see current market volatility negatively impact member sentiment, it is now crucial for funds to proactively offer members reassurance using timely and meaningful interactions. fs

never set ourselves to be the lowest cost in every category, we are a low-cost provider...

The super fund introduced Super View, a new online data tool allowing members to see the identity, value and weightings of their investments.

The tool provides members the ability to see how their money is invested across a range of asset classes and derivatives, including unlisted assets.

It also allows users to scope out either an asset class or regional level to sector specific industries and companies and click through to see the fund’s voting history for each company.

The data tool complements, but is separate to, the fund’s existing portfolio holdings disclosures.

Active Super chief executive Phil Stockwell said that, in addition to providing detailed portfolio information and data that is now required under the PHD regulations, the super fund has gone one step further by offering members a proprietary online data visualisation platform.

“We asked some of our members what investment data they wanted represented in a visually rich manner. Most responded by requesting to see the exposure of global investments and the ability to easily see the industries and companies the fund invests in,” he said.

Active Super chief member experience and growth officer Chantal Walker said: “This tool further enhances our transparency and elevates our multichannel member engagement experience.”

“It supports our ambition to be a leading and innovative digital super fund.” fs

The

Mercer analysis of publicly available retirement income strategy summaries shows a great disparity between super funds’ approaches.

Under the requirements of the Retirement Income Covenant, trustees set out how they’ll help members with their retirement outcomes, making summaries publicly available in July.

Mercer said: “We found variations in size, detail, target audience and messaging.”

“Some trustees have adopted a compliance-based approach, while others focus on embracing the intent of the Covenant obligations.”

The funds Mercer reviewed all chose to approach their RIC strategy in one of two ways: targeting industry regulators, experts and interested members, or targeting fund members.

The Covenant requires trustees to specify the members covered, the meaning of retirement income and the period of retirement, including this information in the strategy. But there is no requirement for these de -

terminations to be in the summary, Mercer explained.

Around 50% of funds disclosed their key determinations in their summaries but they weren’t consistent, the research indicated.

There were inconsistencies in the ages of members covered by strategies and periods of retirement, Mercer said.

Definitions of retirement income were also varying, with about 60% of funds using the Covenant’s minimum definition of retirement income, being payments a beneficiary receives from their super fund plus Age Pension.

Contrastingly, other funds definitions provisioned for the inclusion of additional sources of income.

“It raises the question of how these funds will obtain this information and, in the absence of innovative changes to legislation, this is presumably reliant on the member providing it to the fund,” Mercer said.

Moreover, demonstrable of funds’ RIC strategy polarity, only half of the funds reviewed highlighted member’s access to financial advice. fs

Members of funds that failed the inaugural Your Future, Your Super (YFYS) performance test aren’t leaving, with new modelling showing just 10% have found a new fund.

According to Industry Super Australia (ISA) analysis, only 10% of members switched out of the super funds that failed the performance test. However, 850,000 members failed to leave their “dud” super product, costing them $1.6 billion.

ISA modeling shows if a member on the median wage with a balance of $50,000 stayed with one of the poorest performing funds for the next decade they could be approximately $25,000 worse off.

If a 30-year-old was stapled to one of these dud funds for the rest of their working life, they could be $225,000 worse off at retirement.

ISA warned that further losses could accrue because of the previous government’s stapling

reform that can tie members to failing funds unless they act.

As previously reported by Financial Standard, YFYS stapling requirements tied around one million members to a super fund that’s failed APRA’s performance test.

While members can leave underperforming funds, most Australians don’t know the effects of the YFYS reforms and are generally detached from their super.

“This policy (stapling) was designed to get members to switch, but the inaction combined with the stapling reform will mean members are stuck in dud funds for longer,” ISA said.

“While the stapling reform has stopped the future proliferation of unintended multiple accounts it needs to be linked to the performance test so that members can only be stapled to a fund that passes.” fs

Cassandra

BaldiniAware Super has launched its real estate arm and intends to hold $7 billion in assets within five years.

First announced in June 2022, Aware Real Estate will actively manage the super fund’s directly owned Australian living, industrial, office and mixed-use property portfolio.

The portfolio currently consists of 11 operational assets with 99% occupancy and eight development sites in various stages of planning.

Aware Real Estate's chief executive Michelle McNally said the business is a reflection and reinforcement of Aware Super’s commitment to delivering strong risk-adjusted returns to its members.

"We already have a $1.7 billion real estate portfolio, which we’re excited to further expand in the Australian market with an initial focus on industrial, living, and mixed-use sectors," she explained.

Aware Super said the platform is part of its ongoing commitment to lower member fees, its deputy chief investment officer Damien Webb commented that it will also diversify the fund’s real estate holdings to deliver returns and strengthen member retirement security.

"As part of our strategy to lower fees and deliver strong returns for our 1.1 million members, we’re aiming to increase our internally managed portfolio across all asset classes to 50% by 2025," he added.

Altis Property Partners, a long-running partner of Aware Super, is assisting in the establishment of the new real estate platform by "providing invaluable support services." fs

Chloe

WalkerAppearing on a panel at the Conference for Major Super Funds, Cbus chair Wayne Swan warned the industry has a fight on its hands when it comes to big structural reforms moving forward.

“I was in the parliament when we started the Super Guarantee 30 years ago, and I've been a participant looking at it from the outside and now from within,” Swan said.

“I can say what I've found now from within is that I fully understand just how important the collaborative model is, the model of employers and unions getting together as trustees on a profitto-member model.”

Now, he said, super funds have got to decide how to reinvigorate the profit-tomember model, the collaborative model of unions and employers, to meet the attacks which are going to continue to come over the next 30 years.

“We need to find the next generation of CFOs, CIOs, and trustees that are going to breathe much more life into that collaborative model, as it continues to be attacked because it's too commercial,” he said.

Spirit Super independent chair Naomi Edwards shared a slightly different perspective.

“For the last 10 years we've been in

the valley of regulatory terror awaiting what new changes will arise, and I think there'll be a breather from that,” she said.

Now, she said, the new valley of terror that super funds are entering is not regulatory or political, but competitive.

“I think that the competition is not primarily of industry super funds, retail funds, or other funds, as I think we’re now officially “frenemies”,” she said.

“But we're not swimming in our lanes; we're swimming in many funnels nationally across a lot of lanes. And I think that for many of us finding how we succeed and define ourselves with this new competitive threat, let alone new competitive threats that could come from the outside, will be the terrifying thing.

Meanwhile, AustralianSuper trustee director Claire Keating said: “if you don’t like change, don’t be in superannuation.”

“I’ve worked in super for almost 30 years and its changed so many times.

“It seems to be forgotten that responding to constant tinkering and changes and potential changes costs members money, because the preparation we do for things that might happen or might not happen actually takes away from us running the fund for members benefit.” fs

The board of UniSuper will impose a cap on fossil fuel exposure of 7% and has divested from companies that generate more than 10% of revenue from the extraction and production of thermal coal.

UniSuper has issued its fifth annual climate risk report, detailing the $108 billion super fund’s progress towards its net zero 2050 target and activities around climate risk management.

“Decarbonisation will be a pervasive theme for at least the next decade,” chief investment officer John Pearce said in the report. “It is both essential and inevitable. This will involve a much greater share of renewables as a baseload energy source and a phasing out of fossil fuels.”

In September 2020, UniSuper committed to a net zero portfolio by 2050 and a 45% reduction by 2030 through a combination of company engagement, advocacy and investing in companies that are “instrumental in achieving a net-zero future.”

As of 30 June 2022, 2.8% of the fund’s investments were in fossil fuels, up from 2.55% in 2021, which UniSuper said the value of the investments increased due to changes in share prices as opposed to increased allocations.

UniSuper also disclosed that in the last year, 44 of the largest 50 Australian investments set Parisaligned net-zero 2050 targets as well, an increase from 40 in the previous year. fs

The quote

We need to find the next generation of CFOs, CIOs, and trustees that are going to breathe much more life into that collaborative model, as it continues to be attacked because it's too commercial.

Andrew McKean

HESTA has notified AGL, Origin, Santos and Woodside that they’ve been placed on a watchlist under the fund’s engagement escalation framework.

HESTA has written to the chairs of AGL, Origin, Santos and Woodside informing them the companies were placed on the watchlist. The fund outlined its concerns about the disparity between the companies’ strategic targets and the Paris Agreement goals.

Watchlist companies are subject to closer engagement and monitoring. The engagement escalation framework also considers the use of votes against ‘Say on Climate’ resolutions, directors’ elections, support or filing of shareholder resolutions and/or consideration of divestment, where HESTA considers there is inadequate evidence of progress to address risks and it is in members’ best financial interests.

HESTA chief executive Debby Blakey commented the best financial interests of members are served through a timely, equitable and orderly transition to a low carbon economy.

“Each of these companies has a role in mitigating climate risk and reducing emissions in Australia, which will help reduce the systemic climate risk to our members’ portfolio,” Blakey said.

“HESTA has engaged with these companies since at least 2018. While we’ve seen some progress, there’s evidence of a gap between the companies’ commitments and their actions to transition their businesses in line with Paris Agreement goals.”

The fund has sought a response from the companies. fs

The numbers

$23.6tn

The super giant has risen two places and now sits at number 20 with US$169.055 million total asset.

According to annual research conducted by the Thinking Ahead Institute and Pensions & Investments, 15 Australian funds were included in the survey dropping from 16 in 2020.

WTW Australia director of investments Jonathan Grigg said in general the prominence of Australian funds within the survey wane modestly.

“Most Australian funds included fell in the rankings relative to last year, partly due to a weakening Australian dollar over the course of 2021,” he explained.

“However, AustralianSuper has bucked this trend, its growth is, in part, due to consolidation within the Australian superannuation industry, with AustralianSuper a beneficiary of this in terms of increased fund size.”

He added the trend of consolidation has intensified as a result of the Australian Government’s Your Future, Your Super reforms.

Future Fund jumped one stop 26 with US$147.862 total assets while Aware Super fell seven places to 46 with US$107.511.

Grigg said there is an expectation that Australian funds will come in at higher ends in the future as more mergers occur.

“In 2022 we have already seen Australian Super complete a merger with LUCRF Super, further increasing its scale.”

“The flipside to this is that it could also lead to a lower number of Australian funds included in the survey due to mergers. An example being that two of this year’s top 100 funds, QSuper and Sunsuper, which have recently merged to form the significantly larger Australian Retirement Trust.”

The report further revealed assets under management (AUM) of the top 300 pension funds increased 8.9% to US$23.6 trillion in 2021.

While total AUM has reached record highs the report showed that growth has slowed from 11.5% in 2020 to 8.9% in 2021.

“This was to be expected after a very strong performance in asset markets over 2020. However, the latest performance is enough to take five-year cumulative growth to 50.2% in the period between 2016-2021,” it said. fs

Grattan Institute has warned the government against watering down the Your Future, Your Super reforms, saying it should instead focus on implementing the remaining recommendations of the Productivity Commission.

In its submission, Grattan Institute has argued the reforms are working as intended, leading to better outcomes for members. It said retaining the integrity of the performance test is critical.

“The existing test provides a clear and transparent benchmark with defined consequences. Funds know how they will be assessed ahead of time, and they understand what happens when they fail. This makes the regime enforceable and enhances the effectiveness of the regulator,” Grattan Institute said.

“Introducing subjectivity into the test – such as allowing APRA greater discretion in applying the test – would compromise its integrity and risk recent gains to super fund members. Funds can always find an excuse for their under-performance or high fees, and regulatory risk-aversion suggests this could lead to the policy being toothless. When the regulator does make adverse judgments, these would be exposed to perpetual legal challenges.”

It added that the impact of any changes to the performance test must be weighed against its benefits, noting that all funds that failed the first test have taken steps to merge or reduce fees. Only one that failed that test also failed the second, AMG Super, and is now closed to new members but with lower fees. fs

There's been some pearl clutching in the media recently regarding super funds and the valuation of unlisted assets.

The fact that the super fund with possibly the highest allocation to unlisted assets also topped performance tables for the year to June (Hostplus in case you were wondering) was enough to bring out some of the haters in the audience.

But it isn't just about Hostplus. The dramatic fall in public markets investments in 2022, and the benign to positive returns in in unlisted assets such as private debt and private equity has led to a global debate on the topic.

If you are an investor in unlisted assets, the debates have uncovered two points that you should consider carefully.

The first is the arbitrage argument. If there are two assets with essentially identical investment risks, one would expect the price to be the same. If one is higher than the other (the unlisted version) the rational investor would sell that one and buy the cheaper one (the listed variety).

One major difference between the two assets is ownership. Owners of unlisted assets have a closer relationship with the management of those assets than do owners of listed assets. When things go wrong, they have much greater say in how those assets are managed for the future.

Owners of listed assets have much

less power in the management of those assets. While there are rules around public disclosure, the value of these assets can be more effected by what economists call "externalities". These are factors outside of the control of management and owners, such as contagion in credit markets or a general bear market in tech stocks.

The other argument is that not knowing the "true" price of unlisted assets is a benefit to owners. It's a feature of the unlisted market. But how could a deficit of information be a benefit?

As human beings, we tend to act on new information. Not all action is good for us. Consider the hot new actively managed equities fund with great performance, but high management fees.

Investors pile in, leaving less well performing products (which may consequently recover). The new fund starts to underperform. Returns might still look good over the longer term, but the return to actual investors is lower than the reported returns. This is the difference between the timeweighted rate of return and the money-weighted rate of return. Is there a table out there that shows the difference? I haven't seen one.

Maybe not knowing about the new fund would give investors better returns. Maybe if they only had cheaper index funds to invest in they would be better off in the long run?

It's no surprise that the Hostplus default option has the highest autocorrelation of any default super option.

We all look at an issue from our own perspectives based on our experience, our knowledge and our belief systems.

My investment belief system is based on statistics. I believe that investment returns are characterised by the shape of the distribution of returns. It can lean to the left, it can lean to the right. It can have fat tails. All of these things mean something and I personally have a lot invested in the time and effort it took to understand those meanings. Maybe that's why I value them.

Unlisted assets, however, have an additional feature brought on by the fact that assets are valued at a point in time (always in the past). They have autocorrelation. This means that the latest valuation price is dependent on previous valuations. Put another way, today's valuation price is predictive of future valuation prices.

With a high proportion of unlisted assets, the autocorrelation of the total portfolio (which is still dominated by publicly traded and priced securities) is affected in a profound way. It's no surprise that the Hostplus default option also has the highest autocorrelation of any default super option. fs

Five MySuper products failed the second annual MySuper performance test, with four of them failing for a second time.

The product that failed the performance test for the first time is Westpac Group Plan MySuper. Westpac must now identify the causes of underperformance and set about working to correct it. It must also assess the potential implications of the failure on the fund and its sustainability, developing a plan to close the product and move members to another, if it becomes necessary.

Meanwhile, BT's MySuper option was one of the four to fail the test for a second time. The others were Australian Catholic Superannuation and Retirement Fund's LifetimeOne, EISS Super's MySuper - Balanced and AMG Super.

All but AMG Super have already made moves to merge with other funds. ACSRF is currently undertaking a merger with UniSuper, EISS Super is merging with Cbus and BT's superannuation products will soon move to Mercer.

EISS Super told members it was disappointed to inform them it had failed again, while ACSRF has outlined members' options in the wake of the result.

Combined, the failed products are home to about 600,000 members and close to $28 billion in retirement savings.

Those that failed for a second time have until September 28 to notify their members. They can now not take on any new members and cannot be offered as a default fund for any employers. They must also return any contributions made by new members after today.

APRA said it will be engaging with the four trustees to ensure members achieve better outcomes as quickly and safely as possible. fs

Cassandra

BaldiniChant West has welcomed the proposed pause in the Your Future, Your Super (YFYS) performance test, saying it’s in the best interest of super fund members.

over different timeframes and an administration fees metric. This would provide a much fuller picture of overall performance,” he said.

The test should

a range of different metrics that provide more information on performance over various periods, risk-adjusted returns over different time frames and an administration fees metric.

Chant West general manager Ian Fryer explained there’s been several unintended consequences of the proposed test and many funds have been forced to adopt a shorter-term focus to ensure they pass.

“This has often been accompanied by less portfolio diversification to better track the test’s benchmarks, and unfortunately this is the time in the cycle that diversification is so critical,” he commented.

In addition, Fryer said many Choice products are ill-suited to assessment using the standard benchmarks and believed it would be better to come up with a test that caters to the full breadth of choice investment options.

“The test should include a range of different metrics that provide more information on performance over various periods, risk-adjusted returns

Separately, commenting on the Quality of Advice Review’s proposals paper, Zenith Investment Partners chief executive David Wright said he is not satisfied with Levy's proposal to deregulate general advice.

“As an investment research business, we are supportive of the QAR and its objectives. We remain a strong advocate of the value of quality advice and believe it should be more broadly available to consumers. However, the recommendation to deregulate general advice may have an adverse effect,” he said.

Wright explained while the firm does not provide personal advice it still feels the replacement of best interest obligations with obligations to provide ‘good advice’ may have the unintended consequences of lowering the quality of advice to consumers and the standards of advice across the industry as a whole. fs

Australia’s retirement system has been awarded a B+ by Mercer and the CFA Institute in their 2022 Global Pension Index, ranking sixth overall for the second consecutive year.

The index covers 44 retirement systems around the world, measuring them on adequacy, sustainability, and integrity. Iceland, Netherlands, and Denmark received the top marks, followed by Israel and Finland.

Overall, Australia scored 76.8 out of a possible 100. It scored 70.2 for adequacy, 77.2 for sustainability, and 86.8 for integrity.

“Our system has again ranked very strongly and the policy reforms and reviews that are in flight should continue to improve financial outcomes for retirees and their access to financial advice. The increase in the SGC rate to 10.5%, and the Retirement Income

Covenant partially address our weak link with respect to our adequacy score and will help improve our ranking over time,” CFA Institute Board of Governors member Maria Wilton said.

Mercer senior partner David Knox was the lead author of the study. He said the Australian system needs to shift its culture and focus from accumulation to management of balances in retirement.

“The primary purpose of compulsory superannuation has been, for the past thirty years, focused on accumulation of savings for a healthy retirement. Australia has done this well, and the system continues to perform strongly against global pension systems,” he said.

“But there are opportunities for further improvement, particularly when it comes to retirement income. fs

includeAdrian Stewart chief executive Allianz Australia Life Insurance

We are at an inflection point for retirement investing in this country.

The grey tsunami is coming, with millions of Australians set to transition from the wealth accumulation to retirement phase of superannuation over the coming two decades.

The past two years have been difficult amid the uncertainty of the pandemic and with inflationary pressures rising following the latest ABS data its only set to get tougher for Australians in retirement or looking to retire.

However, it has crystallised Australia's retirement conundrum needs action.

It's time to acknowledge the goals for retirement are different

Transitioning to retirement the focus shifts from performance to generating a reliable, stable income that can be used to finance a comfortable lifestyle.

We need to expand the focus from achieving standardised pre-retirement target figures to giving retirees the confidence that it's going to last.

According to the Association of Superannuation Funds of Australia (ASFA), a couple will need $640,000 in super savings at retirement, while singles need $545,000, to achieve a "comfortable" lifestyle. The targets assume retirees own their home outright and are not paying rent or a mortgage.

Allianz Retire+ research conducted in the second half of 2021 unsurprisingly found that three in four retirees

are not confident about how long their money will last in retirement. Leading retirees to 'under spend' for fear of running out, also referred to as longevity risk.

The research also found a third of Australians in retirement feared the threat of inflation driving down the purchasing power of their savings - a fear amplified over the past six months.

Which is why we need to start measuring success in terms of creating certainty. Certainty in retirement can be defined as having confidence in receiving an income for the rest of your life, or a guaranteed income. This ensures 'lifestyle protection,' removing the fear of spending money once in retirement.

Capital protection and certainty of income are the two key drivers for retirement portfolio management.

In the last 30 years since superannuation was established in 1992 the financial services industry has been led by investment managers focused on performance in accumulation. The next thirty years will be directed by life companies providing guaranteed lifetime income solutions that deliver income certainty and complement the role of the investment manager.

Life companies have a significant role to play in solving the retirement

The economic landscape is shifting, and we need dedicated products to address the individual needs of retirees by creating flexible solutions that remove the current barriers that exist.

problem. Unlike investment managers, life companies can deliver certainty to retirees because they can deliver a guaranteed lifetime income. They have the scale and capital required to deliver a solution that a retiree might rely on for 30-40 years. Empowering Australians to live comfortably and removing the fear of 'outliving their wealth.'

As one of the only dedicated retirement specialists in the Australian market, we support the call to action for life companies to take a more active role in the retirement sector from APRA deputy chair Helen Rowell last year. We also support the need for further development and innovation in the sector.

Flexibility is crucial for next generation retirement products.

The economic landscape is shifting, and we need dedicated products to address the individual needs of retirees by creating flexible solutions that remove the current barriers that exist.

The retirement income covenant has accelerated this shift as we are seeing trustees and superfunds significantly increase their focus on the retirement solutions offered to members.

However there are limited suitable choices in market. fs

The blind rush to consolidate that gripped the $3.4 trillion superannuation sector in recent times may be finally over, according to First Super chief executive Bill Watson.

Instead of seeing big funds gobbling up smaller rivals, Watson expects more considered mergers that make a difference for members rather than rushed mergers that suit the regulator.

Watson believes that with a change of government, there is a change in focus.

Further, he notes that financial services minister Stephen Jones has publicly said there is a place for diversity within the superannuation sector. Jones does not want the superannuation sector to mirror the banking sector by consisting of four dominant players.

“This is a reversal of the previous government policy for fewer funds that were carried out by the prudential regulator,” Watson says.

“Accordingly, there was unrelenting pressure on funds to merge and achieve scale, creating a super system that looked like the banking system.”

The First Super chief executive says

the message is now more nuanced, and APRA chair Wayne Byres is leading the charge.

Still, while the regulator says it no longer has a merger agenda, Watson goes on to say that dealing with sustainability and investment returns will continue to be hugely important.

“Using a metaphor from the maritime industry, Byres says you plot your course. You know where your destination is. You’ve got to ensure your vessel is seaworthy and your crew capable,” he says.

“But if the ship is unseaworthy and your crew is incompetent, Byres is saying you will still encounter the maritime patrol”.

So it all seems a little less crude now, according to Watson, who has demonstrated that being below APRA's $30 billion benchmark does not necessarily mean funds will achieve lower returns than larger funds.

“We’ve seen with fund mergers there’s been a focus on getting larger to achieve better investment returns. Well, we don’t think that’s the case,” he says.

“The regulator telling us that if

We’ve seen with fund mergers there ’s been a focus on getting larger to achieve better investment returns. Well, we don ’t think that ’s the case.

you’re small, you can’t you don’t have the scale for investment opportunities is just not true.”

And the numbers back him up. According to Rainmaker, over the last 12 months, six of the top 10 funds were below $30 billion, underlining that scale does not automatically deliver outperformance.

Moreover, First Super was among the few to end the year in the black. Its default balanced option returned 1% for the current financial year compared to the median industry return of -3.7%.

The fund ranks in the top five for MySuper/default options over one year.

This is confirmed by new data from Frontier Advisors which concludes that asset allocation was more influential for the investment performance of super funds than size and scale. The figures prove that a small fund can trump behemoths.

Watson concedes though that small funds had a good year.

And, that 12 months is just one data point and with current market volatility, it is too early to say whether this will continue.

Watson believes that the long-running bull market has meant that size has potentially created greater returns. But as he sees it, that return differential will shrink in a bear market.

“And, potentially, the larger you are, the greater the risk and volatility that you'll encounter,” he warns.

“In some areas, the bigger you get, the less opportunity there is in Australia. So, you then have to be more agile, which is why we see the large funds opening up offices in London, New York, and Hong Kong. And that's great for their members as it opens up global opportunities that smaller funds can't directly access.”

The chief executive says it isn't just size that needs addressing - it is returns and service.

Unfortunately, he adds, poor performance doesn't belong to small funds only. What needs to be called out is poor performance irrespective of fund size.

Watson says big funds cannot always deliver scale or investment return benefits to their members as they can create diseconomies that retard some types of investment.

“For instance, they can't invest in Australian small-cap stocks because they would distort the market. And given their forecast growth, they won't be able to actively invest in large caps either,” Watson says.

But can't they take an Australian public company private and achieve higher risk premia and a better return?

Watson agrees but points to the downside, which is a loss of liquidity which has its own problems.

“Our system is constructed so members can switch in and out of options daily or even hourly. So there's a tension between being a long-term investor, but having short-term pressures, which limits the ability to take these longer-term bets in illiquid markets,” he says.

“As a small fund, we can fish in Aus-

tralian small caps pond and private equity mid-market sector.”

What's working for First Super is its $200 million private equity mandate.

“We're putting money into mature cash-producing businesses worth around $50 million,” Watson explains.

“There are no J-curve issues, they're mature businesses, but they need institutional money. While their performance has had ups and downs in the short term, they've been the gift that keeps on giving over the longer term.”

Last year, First Super's private equity program returned almost 30% before tax and after fees.

"So that's meaningful returns for our members with $3.8 billion of funds under management,” he says.

Overall, the chief executive says that he watches three key indicators - net investment returns, the cost of running the fund, and, most importantly, the level of service for members.

“Therefore, in terms of any merger opportunity, we want someone capable of delivering better investment returns, lower costs and maintaining the quality of service,” he says.

Watson says the legislative "guardrails" include the performance test and the heat maps. To those, he wants to add a third guardrail which is service quality.

“Being kept on hold by a contact centre for hours isn't an acceptable service,” he says.

Watson feels that First Super is doing a pretty good job for members with returns, service relative to other funds and administration fees, and he's not bothered by the increasing intensity of regulatory scrutiny.

“Those who look after other people's retirement savings should be scrutinised,” he says.

Despite the performance test and heatmaps, First Super has remained true to its conviction with its active management, strategic asset allocation and asset class selection.

“So we have not changed anything because of these tests. We are underweight emerging markets which have been net positive for members and not detracted from performance test outcomes,” he says.

As for service, First Super has a high-touch model that does come with a cost.

“You can go to a bargainbasement Jetstar kind of operation and look good in the APRA heatmaps without any measure of the quality of the service,” Watson says.

Aside from wrestling with service quality, sustainability, costs and stapling, the rollout of ESG remains a challenge.

“We find that not all managers have embraced the integration of ESG into investment processes. However, our private equity program is applying a bespoke ESG evaluation process that our private equity managers have embraced,” he says.

So how do you then grow your membership base without a merger?

First Super is one of the few funds to launch a KiwiSaver initiative a couple of years ago to allow Kiwis to transfer their money to Australia.

While the number of New Zealanders who roll their money into Australia is not huge, for a fund comprising 46,000, it's a big deal.

And First Super is close to its industry groups which have held up its membership. Timber, manufacturing beds, hard and soft furnishing and kitchen cabinets have all been in high demand.

“This means members have worked continuously through the pandemic,” Watson explains.

“So we've had year-on-year membership growth. Our membership growth initiatives may be sub-scale stuff or a rounding error for large funds, but growth from these initiatives is material for us.”

From where Watson sits, smaller funds, close to their members, investing in their industries, low fees, outperforming, and providing more nuanced and bespoke services to their membership, continue to prove that size isn't everything. fs

...our private equity program is applying a bespoke ESG evaluation process that our private equity managers have embraced.

Meat Industry Employees Superannuation Fund has proved size doesn’t always matter, outdoing industry giants with impressive returns. At the same time, chief executive Katherine Kaspar isn’t in denial about what the future may hold. Andrew McKean writes.

Leading a small super fund isn’t for the faint of heart, resources are limited, leaving little room for error, Meat Industry Employees Superannuation Fund (MIESF) chief executive Katherine Kaspar says.

“Essentially, every decision to do something in a small fund is a decision to not to do something else; so getting prioritisation right is paramount,” she explains.

“Larger funds with larger budgets can have multiple priorities, but we often don’t have that luxury.”

Despite these challenges, Kaspar says being chief executive of a small super fund has been one of the most rewarding experiences she’s had.

“The close-knit and personal nature of a small fund allows you to build a deep connection with members; you can’t help but become a part of their lives,” Kaspar says.

“The benefit being that the closer you are to members, the better you can understand their needs and apply it to an engagement or investment strategy.”

Connecting with members and having a sense of empathy with them is a crucial aspect of Kaspar’s role.

To achieve this, she’s engaged with multiple stakeholders, including members, employers, and unions to understand the unique experiences and challenges of the meat industry.

Kaspar has also spent time unpicking the nature of meat industry work, making sure questions are asked about the presence of labour hire, advancements in automation, and environmental factors like climate change, as they all play a role in shaping the experience of MIESF members.

The meat industry also faces challenges like language barriers and low financial literacy..

“My approach is to take all the insights and experiences from our stakeholders and apply it to supporting each member in the simplest way possible, helping them to be their best selves in retirement,” she says.

“Our strategies are crafted with the goal of not just helping our members reach retirement with a great financial outcome, but also so that they understand their journey and feel confident about where they’re going.”

The support of Australian Meat Industry Employees Union (AMIEU) in improving workers lives is also essential in this regard.

“By law, union representatives have access to work sites and are able to report back to us issues that are happening to, or for, our members, which helps us better understand what’s going on for them,” Kaspar says.

“For example, in the case of a higher number of TPD claims, we can work closely with our union representatives on site to determine the root cause and then share this with our insurer, TAL as well as their employer. By bringing attention to these issues and working towards a resolution, we strive to improve the lives of our members.”

Kaspar says MIESF’s insurance offering is simple and tailored to meet the needs of its members.

“Members require straightforward coverage that protects them on the job, without the added cost of unnecessary and expensive insurance like income protection,” she says.

“Our focus prioritises TPD and life insurance, as they are essential in the case of injuries or accidents that may occur on the job. This aligns with our goal of ensuring members have the necessary coverage to address potential accidents and injuries, while also avoiding account balance erosion.”

We continuously work to align our insurance offerings with the needs of our members in the meat industry, she adds.

Accordingly, approximately 98% of insurance premiums have been paid back to membersas benefits.

“TAL is going to kill me for saying this, but there’s a very close alignment between the premiums members are paying and the member benefits that are being paid out,” Kaspar says.

“This shows that the arrangement we have with TAL is in members’ best financial interests; we’re not charging them for things we’re not giving to them.”

MIESF has achieved exceptional investment performance, ranking second on the annual Your Future, Your Super (YFYS) performance test in 2022. The fund surpassed its annual return benchmark by 1.56%, only beaten by UniSuper (1.59%).

APRA heatmap data also showed that MIESF delivered a 7.54% p.a. eight-year net investment return, ranking sixth. Furthermore, it’s the second highest-returning fund over five years (7.69% p.a.) and three years (6.49% p.a.).

Kaspar highlights that the fund’s eight-year net investment returns relative to the strategic asset allocation benchmark was 1.71%, second only to First Super (1.73%) Whilst over the shorter periods of three and five years, the alpha is even stronger relative to the SAA benchmark by 3.51% p.a. and 2.58% p.a.

“Investments are our main focus, we don’t get distracted by other things; it’s what we do,” she says.

“Our core role is about delivering better retirement outcomes for our members and that predominantly has a financial focus; we know investments are our bread and butter. We don’t have many of the bells and whistles that many of the other funds have, we’re a very simple fund with a very simple offering that’s aligned with who our members are.”

MIESF’s investment strategy aims to prioritise the financial security of its members, considering that many of them are low paid with smaller than average retirement savings.

“We knew our members had their phones in tea rooms and locker areas, so we used QR codes to make it easy for

Inevitably, there will be a point of time, as our members’ needs increase, that we will need to consider a partner, whether it’s a shared services or a merger partner.

them to let their employer know they wanted to join the fund,” Kaspar says.

“It’s been an incredible tool for onboarding and engaging with members.”

This defensive tact has resulted in relative outperformance during challenging market conditions, while also protecting the limited funds of its members from unnecessary risk.

Moreover, MIESF maintains a highly diversified portfolio to help mitigate risk and achieve steady returns for members.

“We pulled back on equities last year while building up our position in cash and adding to government bonds,” Kaspar shares.

“We’ve also been making investments of as little as $10 million in unlisted property, including shopping center funds.”

Looking ahead, Kaspar says that the fund has identified some new investment opportunities, particularly focusing on quant-focused international players with a strong track record in the US. Due to the nature of the fund, it has the liquidity to explore these non-traditional investment opportunities.

Kaspar attributes MIESF’s investment success to MIESF’s directors and chair Chris White and Antipodean Capital founder Craig Ferguson, who acts as an investment advisor to the fund. She also credits chief

investment officer Chris Artis, and direct property management by chief financial officer Chris Salamousas and fund accountant David Gamvrellis.

MIESF is a closed fund, only able to accept employees within the meat industry, which comprises of approximately 60,000 workers at any given time.

Despite the small pool of potential members, the fund has attracted 16,000 members who come from the meat industry; it has just under $1 billion in funds under management (FUM).

Kaspar says to keep in mind that as a closed fund, they can’t make agreements with labour hire companies to attract more members. Fund members need to come through as employees of participating employers in the meat industry (who are generally party to an enterprise bargaining agreement).

Further, the difficulty of gaining members within the meat industry is compounded by competition from other funds like the Australian Meat Industry Superannuation Trust and giant industry funds AustralianSuper and Australian Retirement Trust.

In a bid to get MIESF to stand out from its competitors, Kaspar introduced an “explore-exploit” model at the start of her tenure in March 2021. This approach focuses on maximising current successes and seeking out new op-

portunities. The framework for which was imparted on her by Professor Tushman at Harvard Business School, where Kaspar successfully completed the Advanced Management Program.

In the first year of implementing the model, MIESF introduced a plethora of innovations which Kaspar says haven’t been seen anywhere else in the industry. The first of which was the use of QR codes to enable new members to digitally complete the ATO Choice of Fund application form to nominate MIESF as their fund. This solution enables members to join the fund in the throes of the pandemic when lockdowns restricted personal contact.

“We knew our members had their phones in tea rooms and locker areas, so we used QR codes to make it easy for them to join the fund,” Kaspar says.

“It’s been an incredible tool for onboarding and engaging with members.”

The second innovation MIESF has embraced is a buddy program, which allows members to seek guidance from their peers. The program recognises that MIESF members often seek financial advice from friends and family, and provides a structured, compliant way for them to do so.

“By using the explore-exploit model, we have two unique service offerings that I haven’t seen in other funds. Both of those have paid dividends to help bring our membership to a more stable position.” Kaspar says.

Nevertheless, APRA heatmap sustainability metrics revealed that MIESF had a total account growth rate (three-year average) of -9.23%, the fourth largest decline across all registerable superannuation entities (RSEs).

Also troubling, MIESF had the seventh largest decline in net cash flows (-3.9%) averaged over three years. Over the same period, it also ranked 11th in terms of net rollover decline (-2.8%).

“The fund’s sustainability metrics, as a result of COVID, weren’t great, it’s definitely something we’re cognisant of, and whilst it’s been challenging, we are pleased to see our member numbers stabilise in the past year” Kaspar says.

When it comes to increasing women's representation in superannuation leadership positions, it's important to think creatively and define your own path to success. There's no onesize-fits-all approach or linear path to becoming a chief executive or holding a leadership position, Kaspar says.

Likewise, success is yours to define, so it's crucial to think outside the box and consider alternative avenues to achieving your goals, she adds.

Kaspar continues saying that another important strategy for increasing women’s representation in superannuation leadership is to say yes to the things that scare you.

“I’m not talking about people jumping out of windows or anything crazy like that, but sometimes a bit of fear or discomfort can be a sign that you need to challenge yourself to grow,” she says.

“Don’t discount yourself, be your best advocate; give yourself a push, have a go.”

Another important strategy she imparts is to use your initiative to

take the time to understand the business’ strategy. By proactively seeking out ways to contribute to the company’s goals and to deliver on its objectives, you can demonstrate value and make a tangible impact on the organisation.

“Have some ideas, challenge management, challenge your thinking, other’s thinking, get to work focussed on moving the dial,” Kaspar says.

Finally, she recommends that ambitious professionals surround themselves with people who inspire you to be your best self.

“As the saying goes, you are the average of the five people you spend the most time with,” Kaspar says.

“By surrounding yourself with people who are already where you want to be, you can learn from their experiences, gain valuable insights, and be inspired to achieve your own goals; this is true for success in any industry, including superannuation. Seek out mentors and role models who’ve achieved success in the areas you aspire to, then you can build the confidence and skills to break through the barriers that might be holding you back.”

According to an APRA MySuper Heatmap paper, most RSEs are facing sustainability pressures; more than half of all RSEs experienced backward growth across the all the regulator’s sustainability metrics.

“RSE licensees must take account of growth profiles in their business planning activities and consider the likely effects and risks for member outcomes,” APRA said.

“Sufficient scale is required to support efficient and resilient business models, keep fees and costs low, and financial operational and service improvements expected by members. APRA expects that RSE licensees will consider options to transfer members or otherwise restructure their businesses, particularly where sustainability pressures are significant and/or the growth outlook is weak.”

Regarding the sustainability of its membership base, Kaspar says MIESF will continue to employ a combination of organic and inorganic strategies.

The organic methods include utilising the QR code and buddy programs, as well as engaging with employers. The inorganic growth piece centres on constantly evolving to recognise what’s in the best interest of members, as is a trustee’s fiduciary duty.

“We don’t have a partner, we’re not in discussions with any funds, but I think we should always be thinking, looking, and challenging ourselves to deliver more to our members,” Kaspar says.

When serving as chief executive of Kinetic Super, Kaspar recalls that the fund opted to merge with Sunsuper in 2018 despite not having any regulatory pressure to do so. Instead, the merger was driven by the need to better serve the fund’s young membership base with a more engaging digital experience.

Kaspar foreshadows a similar outcome for MIESF, whereby at some point, the fund may consider a partnership or merger to better serve its members, albeit in the absence of regulatory pressure.

“For us it’s about how we can continue to shift the dial for our members and do more for them, particularly around education and advice including on eligibility for the Age Pension, which will be critically important for most of our members with low retirement savings” Kaspar says.

“Inevitably, there will be a point of time, as our members’ needs increase, that we will need to consider a partner, whether it’s a shared services or a merger partner.” fs

Earn CPD hours by completing the assessment quiz for this article via FS Aspire CPD.

Worth a read because:

This paper explains the development of the RMetrics assessment model as a means of capturing multiple measures of risk-adjusted return for a product and integrating them into a single holistic risk score. The model is then used to compare relative performance of MySuper products over the three-year period to March 2022.

Visit www.financialstandard.com.au and click ‘FS Aspire CPD’ in the menu or call 1300 884 434 to gain access to the platform

Rainmaker Information

Workplace superannuation funds are funds that are available to employers, whether they are private sector companies, public sector agencies or government departments.

A primary feature of workplace funds is that they can take advantage of the business volume that comes from combining the superannuation buying power of many employees. Workplace superannuation funds can offer wholesale discounted fees and are typically cheaper than personal superannuation funds that are available to individual employees.

MySuper products are workplace funds because they can only be offered to employees through their employer. Employers are only allowed to pay default superannuation guarantee (SG) contributions into MySuper products, or funds that offer a MySuper product.

Risk-adjusted return is a term that captures both the level of returns and the quantified risks—such as volatility and other measures—that underly those returns.

They are often combined as ratios so that products with different returns and risks can be compared on a like-for-like basis.

Why RMetrics?

To resolve the multiple ways risk-adjusted investment outcomes are described, Rainmaker developed its RMetrics assessment model to integrate these measures into a unified scorecard. Its purpose is to analyse investment returns, volatility and other standard risk measures and to use these results to tell a coherent story about an investment option or product.

RMetrics shows how investments behaved compared with like-forlike peers. Moreover, each measure, or dimension, of RMetrics, can be assessed discretely or interpreted as part of a composite measure.

By integrating these combined RMetrics measures, Rainmaker can assess a product’s holistic risk score. Investors can then use RMetrics to determine how efficiently a fund’s investment strategy has been implemented.

The RMetrics risk-adjusted performance analysis assessed 673 superannuation investment options offered through 60 superannuation products over a three-year period to March 2022.

The analysis spanned 10 strategic sectors, namely:

• MySuper single strategy or selected lifecycle MySuper products akin to a single strategy

• growth

• balanced

• capital stable

• Environmental, social and governance (ESG)

• Australian equities

• international equities

• property

• fixed interest

• cash.

The RMetrics report analysed each option’s investment performance net of tax and investment fees and gross of administration and member fees.

When a superannuation fund offered more than one option in a sector, flagship options—usually actively managed—were selected to represent that fund.

RMetrics incorporates a variety of risk-return ratios, some of which are dependent on the assumption of ‘normal’ distributions and some that are not. This enables RMetrics to cater for a wide variety of asset classes, investment styles and product types.

The RMetrics assessment model has two core objectives:

• To provide a nuanced view of an investment’s historical monthly returns series matched to its investment objectives.

• To deliver an integrated scorecard that quantifies how an investment has performed relative to its peers.

Sharpe ratio

The Sharpe ratio is a measure of risk-adjusted return. It measures the excess return of an investment over the risk-free rate—in reality, the average bank bill rate for the previous three years, divided by the standard deviation —volatility—of the investment’s annualised return.

The risk-free rate is the rate of return on an investment with no risk, such as a government bond or an equivalent cash rate, with the excess return being the return above that risk-free rate. The standard deviation is a measure of the volatility of the investment’s returns. It does not matter if that volatility was the result of high or low returns as this ratio assumes returns are normally distributed.

The Sortino ratio also measures risk-adjusted returns. It measures the excess return above the risk-free rate of return per unit of downside risk. Downside risk or deviation is the volatility of monthly returns that are negative, or which are below a specified threshold. Two superannuation funds might have the same return and volatility, but if one fund has achieved this with lower downside risk it is, according to this measure, superior.

Another risk-return performance measure that is defined as the ratio of gains above a risk-free rate of return to losses, by

captures both the level quantified risks—such other measures—that underly those returns.

With no agreement on which measure best defines risk-adjusted return, Rainmaker developed this composite measure— CRAR—that combines the rank scores for funds across a range of popular riskadjusted measures.

frequency. The omega ratio disregards the size of the gains or losses. It simply counts the number of monthly returns above the threshold rate and divides this by the number below the threshold. Unlike the Sharpe and Sortino ratios, it does not assume normality of the returns’ distribution.

This ratio measures the proportion of total gains to total losses over a period of time. Gains are the sum of all positive monthly returns over the period, while losses are the sum of all negative monthly returns. The difference is the return that goes to the investor.

The ratio of gains to losses helps analysts compare investments that have different volatility profiles as these

are not dependent on the absolute size of positive and negative returns.

Understanding returns’ distributions

RMetrics places considerable emphasis on comparing the distribution of monthly returns, and so calculates the four moments of the returns’ distribution, namely:

• the average or mean

• the volatility or annualised standard deviation

• skewness

• kurtosis.

Skewness and kurtosis refer to the shape of the tails of a return distribution and determine how normal the distribution is compared with its peers.

Skewness describes the shape of the distribution curve and whether it is ‘skewed’ to the left or right of the mean. Most people are familiar with the so-called ‘bell curve’ of a statistical distribution. In a classic bell curve, the distribution to the left of the mean is the mirror image of the distribution to the right of the mean.

When a distribution has a negative skew, it leans to the

right like a wave about to break. An investor in a product with negative skew would expect to see lots of small positive returns and fewer, but larger in an absolute sense, negative returns.

Investors in products with negative skew get used to positive returns and tend to be surprised when large negative returns hurt the value of their investment.

Conversely, investors in products with positive skew can