Research by the Forging Intersectional Feminist Futures (FIFF) Network Philippines

Published by the ASEAN SOGIE Caucus (May 2024)

Analysis and Writing by Kareen Kristeen V. Bughaw (Visayas LBTQ Network)

Editing by Jose Monfred Sy (UP Center for Integrative and Development StudiesProgram on Alternative Development)

Layout by Angelica Grace L Carpio (Youth for Mental Health Coalition, Inc )

Research tool (ICNAT) development by Alvin John J. Neyra (IMGLAD), Rocky B. Rinabor (Pioneer Filipino Transgender men Movement), Shiela May I. Aggarao (Nationwide Organization of Visually-Impaired Empowered Ladies), and Karla Maria R Henson (Life Haven)

Special thanks to Rosalina P. Bayan (Kanlungan Center Foundation) and Cristina V. Lomoljo (BDEV Child Protection) for their translation of the FIFF guiding principles and Alaina B. Dela Peña (Philippine Anti-Discrimination Alliance of Youth Leaders Inc.) for project coordination.

Finally, acknowledgments are due to the following for their work on the preresearch consultative workshops that defined the goal and objectives of the project: Jose Monfred Sy (UP-CIDS), Marianne Faith B. Sadicon (Liyab & Camp Queer), and Genica Faye E. Bucao (ASEAN SOGIE Caucus).

In recent years, it has become clear that while there is greater recognition of the need to work for gender equality and social justice in the Philippines, those who undertake this worthy endeavor are concomitantly facing economic, social, and political obstacles. Adding to the inherently patriarchal Filipino culture that enables gender-based discrimination, since 2016 the national government has pushed and popularized the narrative that groups and non-government organizations representing and defending the rights and interests of marginalized sectors are anti-government or worse, terrorist fronts. Amidst this inhospitable socio-political climate, a group of Filipino human rights workers advocating for intersectional feminism met in March 2023 to discuss how they can help each other and move forward together.

This paper takes its title from the Bisaya word for community: dakbalangay. The word traces its origin from the words dako (big) and balangay, the boat that housed and carried pre-colonial Filipino families across the archipelago, as far back as 320 AD. Dakbalangay is now rarely used even in the Visayas. The preferred term is the transliterated komunidad. The researchers chose the metaphor of the dakbalangay to illustrate that communal sharing of resources is an ancient Filipino practice. It further underscores the aim to gather qualitative evidence to build the case for building a community of care for individuals and groups working for gender equality and social justice in the Philippines.

The research team conducted desk research and developed an Intersectional Care Needs Assessment Tool (ICNAT) to be used in qualitative interviews with members of the Forging Intersectional Feminist Futures (FIFF) Network in the Philippines.

The first balangay boat discovered in Butuan in 1976 was carbon-dated and established to have been built in 320 AD.

The ICNAT was made by a team of FIFF network members representing different marginalized groups, endeavoring to maintain inclusivity and intersectionality even in instrument development. The tool development and data collection team was composed of representatives from Initiatives and Movement for Gender Liberation Against Discrimination (IMGLAD), Nationwide Organization for Visually-Impaired Empowered Ladies (NOVEL), Pioneer Filipino Transgender Men Movement (PFTM), Kanlungan Center Foundation, Life Haven Philippines, and BDEV Child Protection Inc.

The tool and this paper will aim to answer the following specific research questions: What is a community of care? How and where did the term originate?

1. Is it being practiced in the Philippines? 2. Why is there a need for Filipino human rights workers to have a community of care? What is their current situation across the country?

3. Is there quantitative data on the following? 4.

a. Tyranny of the norm (patriarchy, heteronormativity)

Shrinking democratic and civic spaces

b. Gender-based Discrimination

c. Lack of funding or inadequate resource mobilization

e.

d. What are the current capacities of the FIFF network in establishing a community of care?

The tool was administered online to members of the FIFF Network and gathered 35 responses from 14 of 21 organizations. The research group has resolved that the tool will be shared to other allied groups or future members of the network, which shall result in future updates to the quantitative data presented in this paper.

The FIFF Network conducted a workshop in November 2022, attended by groups and organizations from around the country that are currently doing development and humanitarian work. In the said event, it was ascertained that a more intersectional approach is needed to address the socio-political and economic issues that are plaguing the sector. With members used to operating in silos, existing solutions to these problems did not achieve their full potential or impact.

In March 2023, a second workshop among the network members produced the impetus and subsequent agreement to implement a new intersectional and solidarity-driven solution: the establishment of a community of care. This community of care recognizes that the entire network is in the same boat, facing the same problems of social oppression, political persecution, and disenfranchisement. This community of care aims to implement intersectionality via contextually appropriate activities leveraging indigenous and local systems and resources, joint advocacy campaigns, inclusive knowledge production and sharing, shared resource and protection mechanisms, and more.

Anthropological evidence shows that primitive hunting and gathering societies practiced communal living, sharing food and other resources among tribe members. While this is still being practiced by many Native American and indigenous cultures, centuries of assimilation have nearly wiped out the practice. For a while, communes were very popular in the 1960s to 1970s in the USA, perpetuated in part by the hippie culture. But generally, it was isolated to the academic and artist communities, as Community Psychology was developed in the same time period (Kendra, 2023). This multidisciplinary academic branch became very much involved in community-based action research to develop solutions for sociopolitical disenfranchisement, lack of economic opportunities and mental health advocacies.

Similarly, communal care was widely practiced in pre-colonial Philippines and it has survived into the present, especially among indigenous groups. There are many local terms for this: dajong or dayong, binnadang, zakat, among others (Bughaw & Solano, 2021). Dajong (to carry together) involves a community sinking fund, from which money for weddings, burials, hospitalizations and disaster aid is taken. Those that cannot contribute money will provide their services in kind, such as cleaning the environs, butchering pigs and cows for the events, and decorating or sewing clothes and dresses.

In the development sector, particularly among those influenced by the liberal and progressive ideologies of the 1960s to the 2000s, solidarity-based support mechanisms still exist to counter the social structures that oppress the Filipino people in the 21st century. This is because most NGOs in the Philippines originated in social movements or church-based social action programs that addressed social inequities (Hilhorst, 2003). Additionally, there is a definite history of women-led organizations. The first two documented civic organizations in the Philippines were decidedly women-led, the Women’s Red Cross Association in 1899 and the Women’s League for Peace in 1905. Both arose from a need to provide humanitarian relief during the Philippine-American war and after the US took control of the country. These organizations carried forward the women’s emancipation and suffragette movements in the country. Certainly, feminism is not a new concept in this country and indeed has intersected many sectors that were soon represented by civil society organizations. One of the most controversial and popular groups, GABRIELA was formed in 1984 as an alliance of women against the perceived tyranny of the Marcos administration. Since then, it has been a national women’s party, an umbrella group that counts 200 grassroots women’s groups as members and commanded between half a million to 1.3 million votes for congressional seats since 2004. The group’s local chapters in the cities have been noted for its collective action advocacy and programs.

The researcher, as a volunteer of GABRIELA in Cebu City in the 2000s, saw how women members pooled money for each other’s medical needs and conducted garage sales to raise money for health missions. Members who were financially well off pledged for providing transportation allowances and mobile phone load for for providing transportation allowances and mobile phone load for the more active and/or full-time volunteers. load for the more active and/or full-time volunteers. Similarly, the researchers have observed how small Similarly, the researchers have observed how small NGOs in Philippine regional centers are small NGOs in Philippine regional centers are kept alive by pooling of resources and logistical support from local stakeholders. logistical support from local stakeholders. This support usually involves free use of

The Philippines has been labeled as one of the most LGBT-friendly countries in Southeast Asia (Manalastas & Torre, 2016) but the LGBTQI+ community must still live and navigate through the country’s heterosexist patriarchy (Gamboa et.al, 2020). In such a culture, they encounter daily that they are psychologically weak and incompetent. Even today, Cebuano activists still actively call out local media for using the word “mahuyang” (literally, weak) to refer to gays in their publications and broadcasts. The country being the “last bastion of Catholicism” in Asia further perpetuates the perception that LGBTQI+ people are sinners, and they deserved discrimination, abuse and even rape as punishment. In the wake of the killing of trans woman Jennifer Laude in 2014 by US Marine Lance Corporal Scott Pemberton in Olongapo City, Philippines, many locals were of the opinion that Jennifer got what she deserved for dressing up and pretending to be a woman.

On the other hand, Jennifer’s murder became the impetus for an unprecedented show of solidarity not only among LGBTQI+ groups across the country but also with their allied organizations. Many members of FIFF Network organizations participated in the protests, both online and on the streets. On Facebook, numerous threads carried discussion on the all important question: Are trans women, women? Transgender rights and SOGIESC awareness grew especially among the millennials and Gen Z who were coming into their teens exponentially more politically aware than their parents and grandparents.

With this push towards awareness, today more people are bravely coming out. Openly LGBTQI+ politicians in the country are expected to help in pushing for the SOGIE Bill to be passed. However, they too face discriminatory tokenism by their colleagues. They are cited as evidence of inclusion but are at the receiving end of ad hominem attacks on the basis of their sexuality. Frankie, a barangay official, is documented in an Ateneo de Manila research (Gamboa et.al, 2020) as being pronounced untrustworthy by fellow officials because of his gender reassignment surgery and multiple boyfriends.

All these examples lead us to the question that got us here in the first place: why do people form NGOs? As discussed above, the reasons lie mostly in humanitarianism and social justice. There is an unequal distribution of wealth, leading to increased vulnerability to disaster and poverty. As one of the most disaster-prone countries in the world, it is inevitable that human rights workers also become humanitarian workers, shifting between community development and disaster preparedness programs in any given year. With the lack of disaster-resilient public infrastructure, social services, and poverty, forming an NGO is also a political act to counter a deprivation of human rights. Criticism of traditional relief models that perpetuate aid dependency, patron politics, and government corruption led towards more participatory and inclusive community-based disaster management (Luna, 2001). It thus stands to reason that solidarity will naturally arise among those who work as human rights defenders. Historically and politically, the bases for communities of care exist because we are, after all, in the same boat.

As a community or a dakbalangay, the FIFF Network has 14 active members. Established in 2021, it originally had 21 member organizations. These groups represented the country’s marginalized sectors and development workers who were working with these organizations. Table 1 lists the said formations.

Organization

Association of Positive Women Advocates Inc (APWAI)

BDEV Child Protection

Camp Queer

IMGLAD

Intersex Philippines

Kanlungan Center Foundation

Lakanbini Advocates

Life Haven

Liyab

Mujer LGBT Organization

Sector Represented/Served

Geographical Areas Served

Women Nationwide

Children Region X

LGBTQI+ Nationwide

LGBTQI+

BARMM, Region X, Region XII

LGBTQI+ (Intersex) Nationwide

Migrant Workers/Victims of Human Trafficking & Abuse Nationwide

LGBTQI+ Nationwide

Persons with Disabilities Nationwide

LGBTQI+ Nationwide

LGBTQI+ Zamboanga Peninsula (Region IX); Northern Mindanao (Region X); Davao Region (Region XI); Soccsksargen (Region XII); Caraga (Region XIII); Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (ARMM)

Table 1. FIFF Network ProfileOrganization

NOVEL

PANTAY

PFTM

PHRIC

Pinoy Deaf Rainbow

Tebtebba

The Climate Reality Project Philippines

UP CIDS Program on Alternative Development

Visayas LBTQ Network

Sector Represented/Served

Visually-Impaired Women Nationwide

LGBTQI+ Youth Nationwide

LGBTQI+ (Trans Men) Nationwide

Victims of Human Rights Violations Nationwide

LGBTQI+ Persons with Disabilities National Capital Region

Indigenous Peoples Cordillera Administrative Region, Mindanao, Areas with IP Groups

Populations Vulnerable to Climate-related Disasters Nationwide

Marginalized Groups (General) Selected areas

LBTQ (Women) Iloilo, Cebu, Negros, Samar/Leyte

Voice for Sexual Rights Human Rights Advocates

Youth for Mental Health Coalition Youth Nationwide

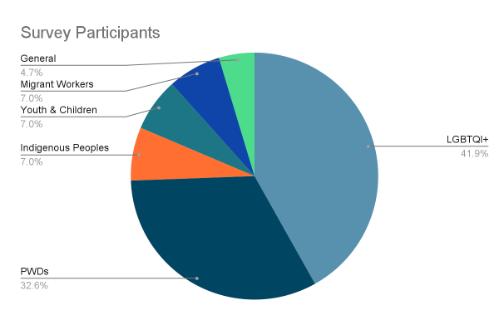

Thirty-five (35) members of sixteen (16) organizations responded to the ICNAT online survey to become a representative sample of the Philippine nonprofit sector and civil society groups advocating for human rights. The following chart shows the marginalized sectors that the survey participants served or represented.

Based on the chart above, 41.9% of the survey respondents identify as LGBTQI+ individuals. It is notable that all of them have reported experiencing a specific form of discrimination. Meanwhile, persons with disabilities made up 32.6% of the participants, of which in turn only two reported not experiencing discrimination. These were two individuals with mental health disabilities. Based on the representative data, those with obvious or visible disabilities were more likely to suffer discrimination than those with psycho-social ones.

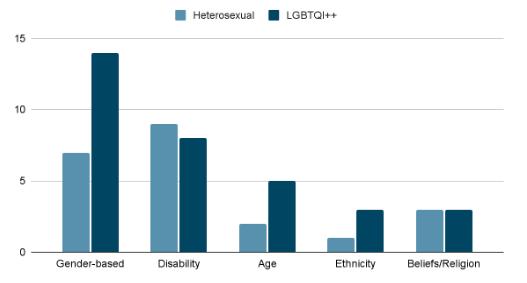

Taking it further, when looking at the data on all the reported types of discrimination, respondents who belonged to 2 or more marginalized groups experienced discrimination on multiple fronts. For example, a homosexual person with a hearing impairment reports being discriminated against for those two attributes (see chart below).

Chart 1. Profile of ICNAT Respondents

The survey data above definitely shows that discrimination based on gender and disability cuts across all members of the gender spectrum. While the numbers are higher for LGBTQI+ individuals, heterosexual women also reported gender-based harassment and violence. This means disability-inclusive and gender-inclusive programming is urgent and must be given top priority.

Among the care needs related to discrimination identified by the respondents are the following: Mental health care and psychosocial first aid, especially for post-trauma counseling; 1. Awareness-raising on rights of persons with disabilities and/or diverse SOGIESC and other marginalized groups; 2. Protection from bullying, gender-based harassment and violence; 3. Legal aid for discrimination-related cases; 4. Discreet reporting mechanisms for discrimination-related cases. 5.

Chart 2 Reported discrimination experienced by survey respondents

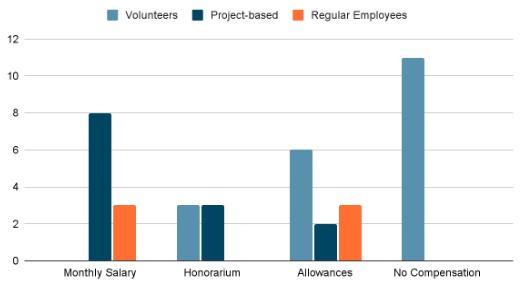

Some of the project-based employees shared that if funding was available they are hired via a limited contract. Once the project or funding ends, they go back to being volunteers. Unfortunately, in those times that funding is unavailable, twenty-five percent (25%) of the respondents spend out of their own pockets to pay for activities. This is inevitable for those who have extra money because seventy percent (70%) of the respondents say that their organizations are struggling in terms of financing their advocacies. Thirty percent (30%) say that they would have liked to go full-time in the organization but because compensation is absent or insufficient, they have to get work elsewhere.

It can be ascertained then that the majority of development workers and human rights advocates do not receive regular salaries for the work that they do. Those that do receive compensation reported that it is often not enough to buy healthier food for oneself and their families.

Figure 2. Majority of the respondents do not receive financial compensation for advocacy work.

3. Majority of the respondents do not receive financial or other benefits.

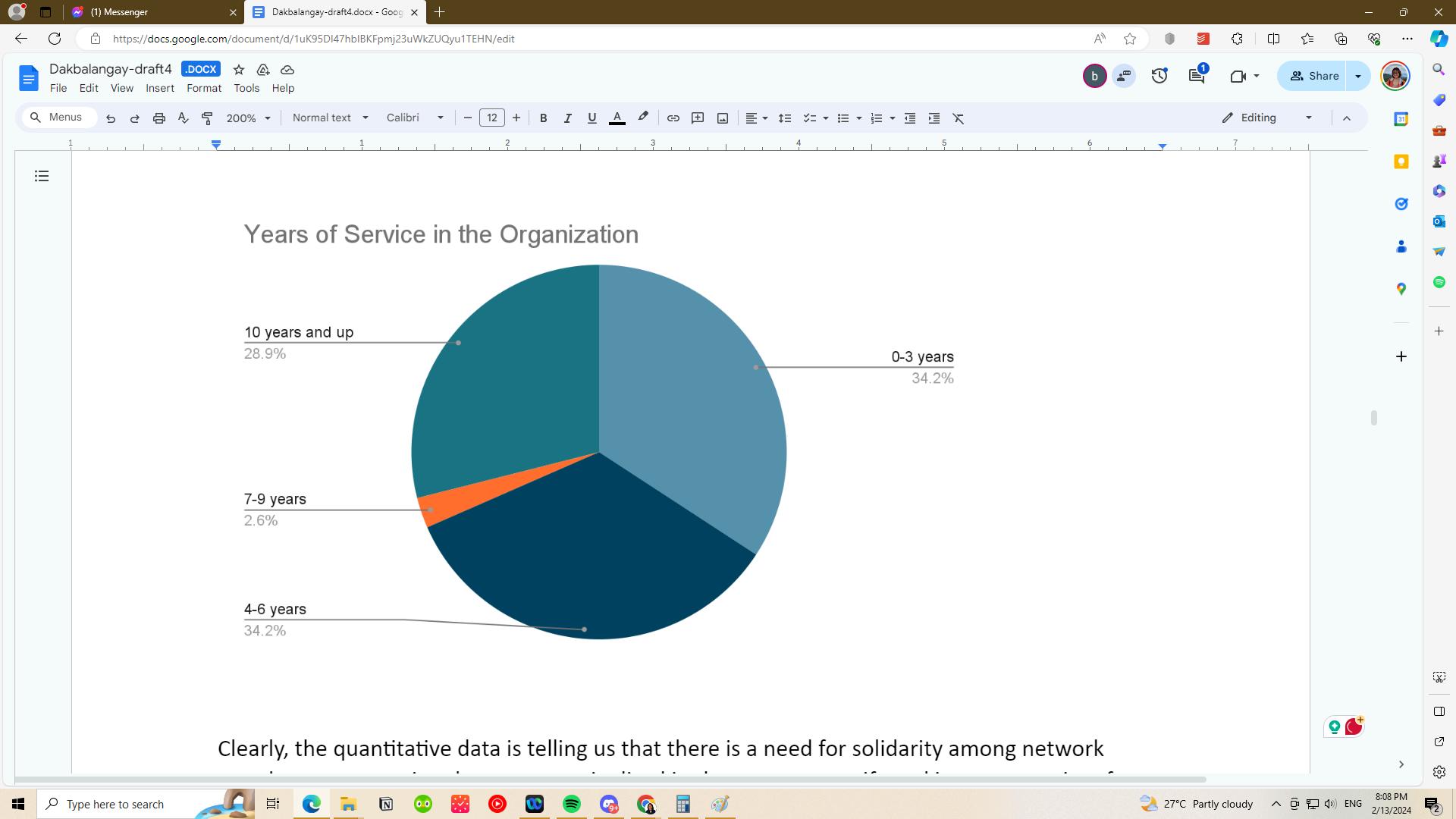

Finally, and amazingly despite the financial constraints, a whopping 28% of the respondents have spent more than 4 years in advocacy work with their respective organizations. They are proud of their efforts but many wish that they had more time to give to it if it only offered better compensation and benefits for them and their families.

Figure

solidarity among network members representing the most marginalized in the country, manifested in a community of care. But let us also take a look at what our qualitative interviews have revealed.

The research data establishes, like many others before it, how the Filipino LGBTQIA+ community is plagued by discrimination and tyranny of the norm. Scholars frequently use Queer Theory as a preferred lens in viewing hegemonic discourses that regulates and standardizes sexual orientation, gender identity and expression, and sexual characteristics (SOGIESC). In general, Filipinos have been noted to subscribe to and perpetuate these often homophobic and even dangerous discourses. Already there are cases of economic deprivation, political disenfranchisement, and loss of life and liberty for LGBTQIA+ activists and human rights defenders in general.

As the FIFF Network continues on its journey towards creating a community of care, let us go back to the metaphor of our balangay. The research team selected five members of the network to symbolize the captain and the rowers. Take note that a balangay, depending on its size, can have up to 100 rowers on each side. To keep our boat from sinking, our network must build our trust and rapport to be in sync. We have to know our members well. Here are 5 case stories to highlight the community’s members and their needs and strengths.

In 2015, Sally was recruited into a job abroad because she wanted to build her own house and support her children through school. She did not have an idea that she had been trafficked until she arrived in Lebanon when a different employer picked her when a different employer picked her up from the airport and her passport was taken away from her. Despite these, she continued to do the work that she was assigned to do. Often sleep-deprived, she tutored children, cleaned the house, provided massage, manicure, and pedicure services, and agreed to do just about anything except sexual favors. When she finally fought back, her employer had her jailed. One would think that jail would be better than being with her employer, but she found herself constantly on guard against sexual harassment. She observed that other women inmates who have been there longer than her are resigned to survive off a life of sexual slavery.

For 6 months in 2017 while she was in jail, Sally’s whereabouts were untraceable. Her husband and children became depressed, resulting in her husband attempting suicide. When she was finally rescued by the Philippine embassy, the employer refused to hand over her belongings and passport, thinking that she couldn’t leave the country without them.

“The embassy won over that attempt and we were able to leave,” Sally shares. “There were quite a number of us on that plane and when the captain announced that we were in Philippine airspace, many of us burst into tears.”

Back home in La Union, Sally was assisted by the Kanlungan Center Foundation to resolve her legal issues and address psychological trauma. With Kanlungan’s international connections, Sally was given a small amount to start her own livelihood venture.

As her financial status improved, Sally eventually became a volunteer for Balabal, a women’s organization affiliated with Kanlungan that provided the same services to migrant workers from Pangasinan, La Union, and Ilocos. Sometimes, they have to render assistance to a migrant worker in real-time, like a rescue from imminent harm or danger. Most of the time, they receive those who were able to come home and help them reintegrate into the community.

Balabal has around 30 members. Sally is one of those. Trained as a paralegal, she files documents and compiles them for the migrant workers. Cases include indictments for human trafficking as well for abuse by foreign clients.

Sally soon stood out because she was very vocal. Every time she conducts case intakes, her experience returns to mind, and she becomes even more strongly convinced that this is where she should be.

“Many of our members were raped and tortured and we often find ourselves in tears while they are sharing,” says Sally. “We felt that we were not protected by our government.”

This she felt even more recently when she faced false accusations from certain sectors about her volunteer work.

She continues: “Is it anti-government to help my fellow migrant workers? We were able to get some abused workers home by our own contacts and resources, after they had asked for help from the government in vain.”

For clients that are still abroad, they ask help from Lawyers Without Borders, depending on the country where they are working. Locally, Kanlungan asks for legal aid contacts from Saint Louis College in La Union.

As for themselves, the humanitarian workers and volunteers who face harassment, Sally laments that resources are scant. They need legal protection, too. She notes that a human rights activist was gunned down recently.

“Our friends in the academe advise us how to handle politicallymotivated harassment. And we are grateful. But in this work, we need all the help we can get. And not just protection, we also need mental health care.”

With low salaries for volunteers and Balabal clients also just recovering, many cannot afford a psychologist. There are only two resources for mental health care in La Union, most are in Baguio and are often expensive, on top of the fare going up to the Cordillera highland city.

Sally is 50 years old. She points out that there should be a new generation, a new set of leaders to carry on Balabal’s and Kanlungan’s work. But with volunteers having just allowances, and no benefits, especially health care, younger people prefer to go back abroad or find corporate jobs to support their families. She feels that with a community of care, needs can be shared between organizations with more resources and those who are struggling or starting out.

Dhelz requested that she be only identified by her nickname. This is her prerogative as an intersex person who has suffered mental distress discrimination. She is 26 years old and a member of Intersex Philippines. She had seen Jeff Cagandahan on TV and reached out to him. She is now a volunteer for the organization while working as a teaching personnel in an elementary school.

Her story is a painful one, but very common among intersex individuals.

Dhelz grew up in a mountain barangay located in the town of San Joaquin, Iloilo. Her parents were farmers so she and her siblings toiled in the fields of palay (rice) and root crops. Early in her life, she was made aware of the plight of poor farmers who had to take out credit from local usurers to pay for fertilizer and pesticides, planting and harvesting equipment, and household needs while waiting for their crops to mature. One of her wishes is that farming families like hers would have some subsidy from the government to cover costs, all the more when they lose their crops to typhoons and floods.

Around the time she was 11-12 years old, Dhelz noticed that she had unusual reproductive organs. She did not have menstrual periods or develop her breasts as expected at adolescence. While her female classmates gained the confidence to wear form-fitting clothes, she became self-conscious and became flustered at how to handle her unusual condition. What made it worse is that her own mother outed her condition to other people after their visit to the doctor when she was 18 years old.

condition. What made it worse is that her own mother outed her condition to other people after their visit to the doctor when she was 18 years old.

“Are you a tomboy? No man will be interested in you! You will be useless to them,” Dhelz remembers being told.

These and other forms of bullying were common to her as she went through high school. She had hoped that someone would learn to love her anyway despite her situation. But when a boy broke off his courting after finding out, she thought she would never find a partner. At the moment however, she has a boyfriend, but they are in a long-distance relationship. The man is aware of her being intersex and has expressed that he is fine with it.

Because of poverty, her parents could not afford college tuition. So after graduating from high school, determined to fulfill her dreams, Dhelz looked for scholarships. Finding none, she decided to be a working student at the school she enrolled in.

Dhelz now lives in the capital in a rented room. She says that her salary as a teacher often comes up short for basic needs, like food and water for drinking.

Aside from food, intersex people need mental health and legal support, Dhelz says. Over 50% of their members have sexual characteristics that are misaligned from their sexual orientation, gender identity and expression. Unfortunately changing their given names and gender markers need legal proceedings.

As a member of Intersex Philippines, Dhelz is confident that with a strong support system, their group can provide support in a community of care. They are very active and may be relied upon during advocacy events as well as humanitarian response activities.

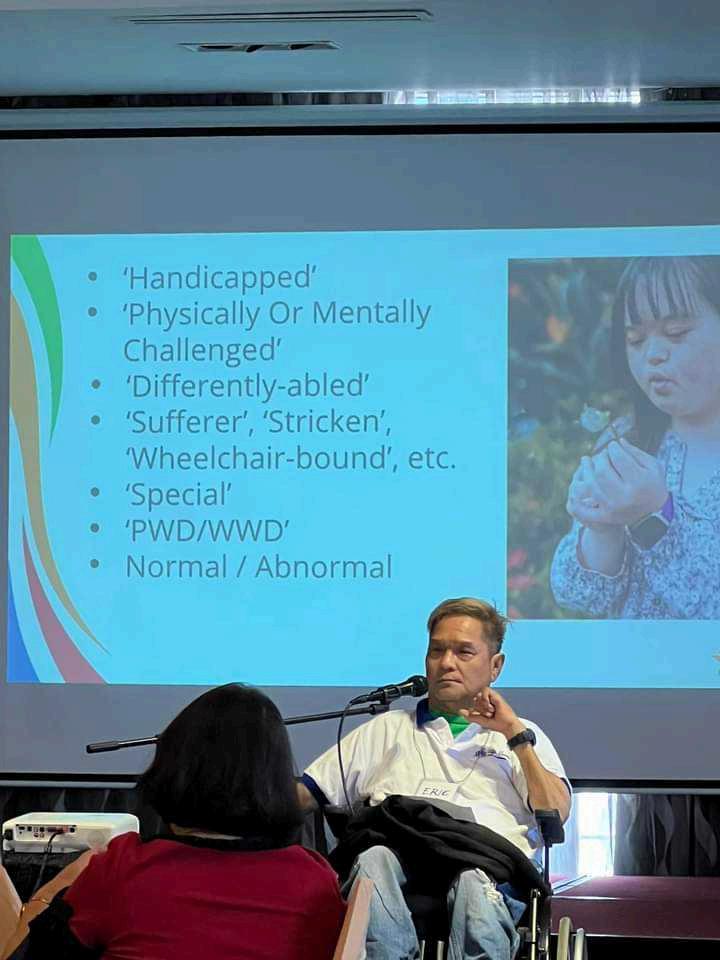

Eric has been a member of Life Haven for 14 years. He explains that their group advocates for the rights of persons with disabilities, equal treatment and government subsidy of personal assistance services to support them in living the lives that they aspire to have. wanted to erase the view that

As a peer counselor of Life Haven, Eric allots part of his time to face-to-face or online sessions with persons with disabilities. These usually involve exploring solutions to disability-related issues such as transportation but at other times, there are also motivational conversations for those going through difficult times. They also conduct peer visit services to share the concept of independent living.

More recently, the group has ventured into disability-inclusive disaster risk reduction activities. In partnership with Christian Blind Mission Philippines, they submitted names of persons with disabilities for aid during the Mayon and Taal eruptions of 2023. They also conduct and facilitate workshops on various topics, including disability desensitization and disability-inclusive development.

Life Haven is based in Valenzuela but it has a network of around 300-500 persons with disabilities all over the Philippines. Aside from peer counseling, they also find sponsors or sources for assistive devices, such as wheelchairs, crutches, walkers, prosthesis and orthosis, and other assistive technologies. Additionally, they offer a good referral network of personal assistants.

“Personal assistants are very important in ensuring that people like us get to live like we did before we acquired our disabilities,” Eric shared. “We have long been asking the government to provide this service but we always get the same answer: don’t you have families to take care of you?”

Eric is 56-years old and a quadriplegic, paralyzed from the waist down. He has a wife and two children. If his wife stops working to take care of him, they would not be able to financially support their family. His children go to school. He doesn’t want them to quit school just so they can assist him. With a personal assistant, he can perform his tasks for Life Haven.

Life Haven is presently lobbying with Congress to pass the Disability Support Bill. They are counting on the support of Quezon City 5th District Representative Patrick Michael “PM” Vargas. But Eric concedes that perhaps fruition will come later rather than sooner. At the moment, they still suffer discrimination as manifested in the lack of disability-inclusive public transportation systems and communication channels.

“Every year, the barangay conducts activities supposedly for persons with disabilities. But these are often for entertainment or recreation such as sports fest or beauty pageants. Then, once in a while, they give out assistive devices, but at very limited numbers,” Eric says.

Life Haven, as part of the FIFF Network, is very willing to provide disability desensitization workshops and other similar interventions to raise the awareness of both network members and nonmembers. In turn, he would be willing to work on joint advocacy activities for intersectional issues.

RC serves with the Youth for Mental Health Coalition (Y4MH) as its National Secretary General.

As a mental health service user diagnosed with a mental health condition in 2018, she sought indepth understanding of mental health to ensure appropriate approaches in advocating for the cause, and thus becoming a member of the organization.

Being part of a volunteer-based organization, RC has not received any remuneration for the work she has been doing for five years. Even so, she emphasized that her experience in being able to support those in need, has been fulfilling. She cited her participation in co-creating the National Guidelines for Ethical and Responsible Reporting and Portrayal of Suicide in the Media, Audiovisual and Films, which Y4MH did in partnership with the Department of Health and the World Health Organization.

Y4MH is a volunteer-based and youth-led non-profit organization specializing in mental health-related policy work in national and local levels, awareness-raising through mental health literacy, facilitating service delivery, and conducting community-based projects addressing grassroot realities. Members of the organization are young people aged 15 - 30 years old.

RC pointed out that mental health medicines and services are expensive. A consultation with a private clinic psychiatrist costs up to 3,000 pesos. This is already steep even for middle-income earners, but all the more so for unpaid volunteers. This is why many mental health service users struggle to access required healthcare.

“During job interviews, I experienced discrimination, when I disclosed my mental health condition,” RC shared.

This stigmatization and discrimination has been negatively affecting RC’s employability and socioeconomic status. It can be surmised that she is but one of many across the country, despite the fact that the Mental Health Act has already been enacted. The Department of Labor and Employment (DOLE) has also issued Guidelines for the Implementation of Mental Health Workplace Policies and Programs for the Private Sector.

RC believes that good governance, including responsiveness of local government units to provide for the mental health needs of its constituents, would make a huge impact. For this reason, she and Y4MH continue to lobby for legislation, both at the national and local levels, to prioritize mental health and improve general health outcomes.

As part of a community of care, RC believes that Y4MH, with its track record of policy lobbying and implementation of mental health programs, could be relied upon to lead in mental health initiatives and programs.

Gen joined the ASEAN SOGIE Caucus in 2022. She had been wanting to learn more about intersectionality so she was very excited about the FIFF project.

In those first few months, she worked on compiling a list of organizations from all over the Philippines to contact for partnership and membership in the FIFF network. The initial list identified 127 organizations that might potentially be interested in taking an intersectional approach to human rights work. Of these 40 expressed interest but only 22 were able to meet up for further talks and eventual membership in the network.

In those first few months, she worked on compiling a list of organizations from all over the Philippines to contact for partnership and membership in the FIFF network. The initial list identified 127 organizations that might potentially be interested in taking an intersectional approach to human rights work. Of these 40 expressed interest but only 22 were able to meet up for further talks and eventual membership in the network.

After the National Opening Partnership Dialogue and finding common difficulties in resource, data and people management, health and wellness support, and policy lobbying, the network held a series of learning exchanges that Gen organized. She remembers doing online sessions to discuss disability-inclusive and accessible digital standards and products, intersection between disability and gender, and the LGBTQI+ movement in the Philippines. These exchanges were led by ASC, NOVEL, and PANTAY. They proved to be necessary in diffusing a much deeper understanding of intersectionality and fostering solidarity for future collaboration.

“What is notable about these sessions is that they weren’t on the original concept note, but because we wanted the process to be inclusive and emergent, when they were requested by the members, we made sure they were held.”

As the representative of the ASEAN SOGIE Caucus, Gen attended several learning opportunities on intersectionality, which helped her in designing the November 2022 workshop. There, network members produced the Guiding Principles of Intersectionality (see Annex 1). This document became the basis for the network to unanimously agree to address their collective concerns by building a community of care in March 2023.

Gen notes that leading the initiative has been a balancing act between guiding the partners towards the fruition of their ideas and making sure that the process is democratic. The intention to have a community-led project in and by itself is what every human rights advocate aspires to. But there is a confluence of factors that deter or delay advocacy campaigns or projects and Gen is happy that the network decided to embark on an evidence-based approach towards a solution that is contextually appropriate to the situation of Filipino human rights workers.

“I’m really glad the partners chose to work on this research project. The concept of “community of care” had been often discussed but never on paper. This has a lot of potential to push the conversation even further,” Gen concluded.

Gen manifests how a captain of the balangay should be: inclusive, open-minded, and innovative. They may be shouting commands so that the people at the oars will synchronize their movements to steer forward but they know that whatever bounty lies on the far offshore is shared with the dakbalangay. That is how our ancestors viewed a community in pre-colonial times. Today, with solidarity in shared resources and a strong community of care, achieving our Sustainable Development Goals is certainly not a far-off dream.

Both the data from the ICNAT survey results and the qualitative interviews prove that human rights workers in the Philippines, represented by the FIFF Network, need a community of care. While the research sample could still improve in terms of inclusion of marginalized groups (notably, the elderly, farmers and fisherfolk, and urban poor) to more accurately represent human rights workers, it bears noting that the network serves a populace that cuts across all sectors. For example, migrant workers being served by Kanlungan often are members of farming and fishing communities. A number of LGBTQI+ members of Pinoy Deaf Rainbow, Visayas LBTQ Network and IMGLAD are urban poor.

Additionally, the issues that attend human rights advocates are also intersectional. Women suffered doubly under socio-political exploitation and patriarchal oppression. From 1969 to 1986, 15% of the 9,000 documented and reported victims of human rights violations were women activists (Sales, 2021).

From both the ICNAT results and key informant interviews, several conclusions may be drawn.

Human rights workers and defenders in the country are themselves victims of many forms of discrimination and harassment. The data clearly shows intersectionality of issues in how they suffer human rights violations on multiple fronts. Sally suffered gender-based violence as a victim of human trafficking and, upon coming home to the Philippines and volunteering to help her fellow migrant workers, became a victim of political harassment. Dhelz was traumatized by long-term discrimination due to her status as an intersex individual. At the same time, she struggled with limited opportunities for scholarship and employment. Meanwhile, RC and Eric also faced practical hardships in finding employment opportunities as persons with disabilities in a country that does not support their needs beyond a certain tokenism. In pre-research consultative workshops, other members of the network had already shared how they were red-tagged for being human rights defenders. This is true for those with previous or current connections with groups that government has labeled “left-leaning”.

2 2

3 3

The majority of human rights workers and defenders have little influence or access to local decision-making platforms. Except for Youth for Mental Health with its work in policy lobbying, most members of the network are facing difficulties in their respective lobbying efforts with the government to enact laws and ordinances that uphold and protect their rights.

4 4

Humanitarian and development organizations and advocacy groups do not have enough access to funding and resources resulting in zero or insufficient compensation and benefits for their staff. The majority of the organizations in the FIFF network do not have core funding or even regular project funding. This is why they only have volunteers or project-based staff. This limits the extent of their advocacy work and subsequently, their sustainability and impact on the community.

There is a precedent for existing solidarity-based resource sharing among Filipino human rights workers. It has been practiced among members of early feminist movements from the 1800s to modern-day women’s organizations. Among the members of the network, there are reported experiences of receiving financial aid and extension of livelihood opportunities, between coworkers.

The network’s diverse membership means that organizations have complementary strengths and weaknesses. Some have a strong background in policy advocacy and lobbying. There are others who have decades of experience in community organizing and mobilization. Still, others have capacities in writing grant proposals and a track record of having these approved. A community of care may come in the form of resource sharing, human or otherwise; coled skills development and capacity-building; and provision of free and affordable health care and social services from shared networks or local governments.

Considering the current capacities and resources of the FIFF Network, the following Community of Care solutions are specifically recommended to be made available to members:

1. Resource Sharing & Management

Proposal Writing Workshops and participatory editing

Co-leading projects that tackle intersectional issues

Resource map of network members

2. Human Rights Education for network members and allied organizations

The Human Rights Situation in the Philippines

SOGIESC & LGBTQI+ Philippine Situationer

Women’s Rights & Gender-based Violence & Discrimination

Disability-inclusive Programming & Filipino Sign Language

Universal Declaration of Human Rights

Core Humanitarian Standards

Climate Change & Gender

Advocacy Campaign Implementation

Risk Communications & Community Engagement

Policy Lobbying at Local & National Government Levels

Introduction to relevant allies and network organizations

Active information sharing among members

Online Community of Practice platform (Facebook group)

Conduct of further research on actual practice of community of care especially on results, positive or negative, and opportunities for sustainability

Inclusion of protection against discrimination in workplace codes of conduct

Discreet handling and reporting of discriminatory practices and actions

Creation of safe spaces at work and in areas of operations

Free or affordable mental health care

Gender- and disability-sensitive mental health care

Free or affordable legal aid for victims of human rights violations including human trafficking, red tagging and political harassment, gender-based violence

Alternative forms of mental health support especially for post-disaster psycho-social debriefing and first aid (creative workshops, theater productions, etc)

Not just service providers, human rights workers and defenders are also a family, a manifestation of “unity in diversity”, and bearers of Filipino indigenous heritage. They are, in essence, a representation of humanity in the global South. To be able to continue to provide the much-needed counterbalance and resistance to socioeconomic and political oppression, they need to band together and support each other to soldier on in the fight to uphold human rights. Philippine NGOs, within a broader network of civil society organizations, have had breakthrough and leading roles in organizing and mobilizing social movements in the country (Clarke, 1998). Thus, a community of care is a logical progression.

Eventually, when establishing a community of care becomes a dominant practice, the meaning of human rights work becomes actualized. Mainstreaming it encourages more people to join in on the cause because they see it as a compelling social obligation to their fellow human beings. With a common understanding of intersectionality, this collective action and support will pave the way to a more just and humane society.

Angeles, Leonora Calderon. Getting the Right Mix of Feminism and Nationalism: The Discourse on the Women Question and Politics of the Women’s Movement in the Philippines. University of the Philippines: 1989.

Buena, Karen. Community Care and the Collective Pursuit Toward a Freeing Society. Philippine Collegian, 6 June 2023. https://phkule.org/article/867/community-care-and-the-collective-pursuittoward-a-freeing-society

Bughaw, Kareen & Solano, Villariez. Dajong: Humanitarian Cash Aid vis a vis Indigenous Self-Help Mechanisms. Disaster Resilience. Anvil Publishing: 2022.

Cherry, Kendra. Community Psychology Explores How Well Individuals Relate to Society Very Well Mind, 21 November 2023 https://www.verywellmind.com/what-is-community-psychology-2794898

Clarke, Gerald. The Politics of NGOs in Southeast Asia Participation and Protest in the Philippines. Routledge: 1998.

Gamboa, Lance Calvin; Ilac, Emerald Jay; Carangan, Athena May Jean; Agida, Julia Izah. Queering Public Leadership: The case of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender leaders in the Philippines. Leadership Vol 1-21. Sage Publications: 2020.

Hilhorst, Dorothea. The Real World of NGOs: Discourses, diversity and development. Ateneo de Manila University: 2003.

Luna, Emmanuel M. Disaster Mitigation and Preparedness: The Case of NGOs in the Philippines. University of the Philippines Press: 2001. Sales, Joy. Gender, Political Detention and Human Rights in the Philippines. Diplomatic History. Oxford University Press: April 2021.

The Fight Against Violence on Women in the Philippines: The Gabriela Experience.

https://www.un.org/womenwatch/daw/vaw/ngocontribute/Gabriela.pdf

The FIFF Project is funded by

The FIFF Regional Consortium is led by

The implementation of FIFF in the Philippines is led by

FIFF Network Philippines: