9 minute read

Ergonomic guidelines for hybrid workspaces

Ensuring productivity and safety

The disruption to office work has been unparalleled in the last few years due to the impacts of COVID-19. As the world moves towards opening the office doors to allow employees to return to an office-based setting, new variants continue to emerge (WHO and ILO, 2021). With so many unknowns, and a desire to allow a return to in-office work, businesses are considering their return-to-work strategies. By Brandy Farris Miller, Anand Subramanian and Jeffrey Fernandez

Advertisement

One trend that emerged from the required remote work brought on by COVID-19 is that businesses understand that much productive work can take place without physically being in the office. The time spend commuting to and from the workplace can either be used to contribute to work productively or can be spent doing things that improve the quality of life. The concept of “great resignation” has also ensured that businesses can no longer compel their staff to be in the physical office full time. Technological advancements have permeated all aspects of life and have provided businesses with the concept of working effectively and efficiently at the office, home, or any other remote location. This flexibility has continued to shape the concept of a “hybrid workplace”. The seamless integration of a physical workplace with the remote workplace will ensure that employees can be productive. This includes determining when and what tasks are most effective to be completed within the traditional office space and what tasks are most effectively worked outside of the traditional work environment (such as home office or remote work) as shown in figure 1. The hybrid workplace could be a mix to varying degrees of an employee working from the office, working from home, a conference room, or any other location; with two extremes of the spectrum being 100% in-office and 100% working from home. Traditionally, office ergonomics has focused on one end of the spectrum (i.e., 100% in-office). In our previous discussion (Ergonomics recommendations for remote work, see GlobalCONTACT 02/2020), we reviewed the use of ergonomic principles for the temporary 100% working from home setup. Here, we aim to address the role of ergonomics in addressing the challenges of returning to the office in a hybrid setup, where office presence is less than full time.

WHAT WILL A RETURN TO THE OFFICE LOOK LIKE?

Increasingly, organizations are looking at periodic attendance in the traditional office. For some organizations and job tasks, this will be ensuring department coverage on-site every day of the week, while for others, it may include meeting onsite for collaborative work that is most effectively performed in person. This reduced census of employees on-site and the related opportunity to reduce the real estate related to office work can produce positive results when implemented with a comprehensive plan. Among the considerations are what type of tasks will be performed and where will people be working.

WHAT TASKS WILL BE PERFORMED?

The goal in ergonomics is to fit the tasks performed to the capabilities of the human while adhering to the acronym ‘N-E-W’ (Neutral posture – Elbow/Eye height – Work Area) (Fernandez & Marley, 2013) to guide workstation setup. Looking at the tasks performed may give clues as to the type of in-office accommodations that are necessary. The requirements of tasks, as it relates to time in the office can be divided into three general categories: return to office full time; return to office only for significant meetings; and return to office partial (ranging from a few days a week to a few days a month).

1. Return to the office full time When tasks require the presence of the same individual regularly in the office (i.e., customer-facing, or other service type employees), many organizations provide this individual with a dedicated workspace. This would be similar to the prepandemic work environment. This allows the workspace that will be used daily to be configured once for a single individual.

2. Return to the office for significant meetings On the other end of the spectrum of employees who will be returning to the office environment, there will be individuals who mainly return to the office environment for meetings.

Fig. 1: Evaluating where tasks are most efefective to be completed is important – in-office or remote.

Compared to the traditional office environment, where every individual had a desk space that was theirs, this “meeting only” employee will, likely, not have an office and primarily be working in conference rooms during their time on-site, in the office.

There are distinct considerations for this type of work primarily in conference rooms. This includes paying attention to the traditional ergonomics risk factors such as duration and body posture (Putz-Anderson, 1988). The assumption previously was that people working in conference rooms are there for a short duration (from one to a few hours) and that they may be primarily taking handwritten notes. Moving forward, these assumptions do not continue to hold true. Conference rooms used for long meetings (half-day, full day, or multi-day) should include the following additions: • laptop peripherals such as external mice, keyboards and monitors • fully adjustable chairs that accommodate a range of users • footrests for use while seated at the common conference room table • Many tables are set at a standard height that requires users of average height or smaller to raise their chair in order to work at elbow height, thus putting additional strain on the underside of the thigh, and allowing for posture variation through regular breaks or allowing participants to stand along a conference room wall.

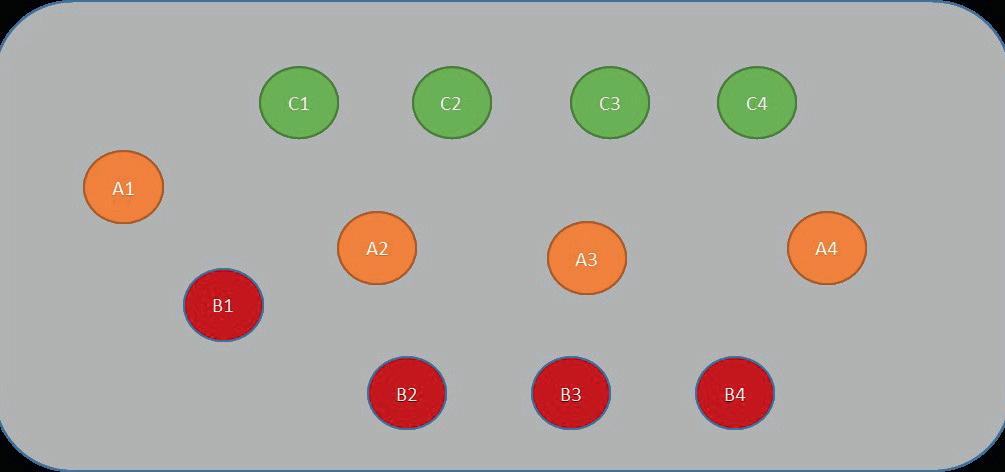

3. Return to office – partial This partial return to the office presents challenges and opportunities in how to efficiently accommodate hybrid employees in offices when they may only be on site a few days a week or a few days a month. The problem of effectively accommodating the ergonomic needs of more people with fewer real estate resources can be solved by repurposing and effectively applying industrial engineering and ergonomics concepts to arrive at possible solutions. These concepts include fully flexible workspaces and A-B-C workspaces.

Fig. 2: A sample spatial arrangement of workspace by A-B-C categories.

DIFFERENT WORKSPACE CONCEPTS

Concept A Fully flexible workspaces refers to providing a workstation solution that accommodates the majority of individuals that could possibly work at a location. In many instances, organizations would need to invest additional initial capital in furniture (such as adjustable height desks or desktop units). Fully flexible workspaces provide maximum accommodation for all employees and do not require extensive scheduling or reservation requirements. Individual employees have the capability of selecting and utilizing any workstation at any point in time. Fully flexible workstations should be equipped with some basic items such as:

• adjustable height work surfaces • alternate seating for those who need it a. larger or taller individuals may need access seats that will accommodate their size b. smaller or shorter individuals may need access to seats that fit them better • appropriate peripherals such as a. external monitor(s) b. docking station c. external keyboard/mouse

Concept B A-B-C workspaces is a way of grouping workstations based on features or parameters so that individuals can select the type of workstation that is appropriate for them and their work needs (e.g., A- medium workstation size; B- small workstation size; C- tall workstation size). A single sharing area would have a mix of these groups of work pods and based on availability or any other method an individual employee can select for a given time window. The percentage of As, Bs, and Cs can be determined during the planning stages to accommodate the maximum population. workspace. In order for this concept to be successful two activities should be conducted: (I) a map of the entire work area, cataloging the dimensions, features, and adjustability for the workstations, seats, and peripherals, and (II) measurements (e.g., elbow height for work surface height) of employees so that they can be categorized and educated as to which pod is most appropriate. With this information in mind, the space can be arranged so that desks accommodating smaller, medium, and tall individuals can be placed throughout the work environment. One organization implanted such a strategy and set some desks so that the work surface were 25 in (63-64 cm), 27 in (68-69 cm) and 29 in (72-73 cm) (figure 2). The working population was then educated as to which workstation height would be most appropriate for their body size. In addition to different work surface heights, similar considerations as mentioned above will also be necessary, including:

I. A-B-C worksurfaces

II. fully adjustable seating • footrests may need to be provided for those that are smaller and cannot work at the minimum adjustable workstation height

III alternate seating for those who need it • larger individuals may need access seats that will accommodate their size • smaller individuals may need seats with short seat pan depth at their workstations

IV. appropriate peripherals such as • external monitor(s) • docking station • external keyboard/mouse

As organizations begin to navigate a return to the office, considerations related to the type of tasks that are being performed by in-office employees can drive decisions related to the design of conference rooms, fully flexible workspaces, or A-B-C workspaces. There are many more considerations for full, effective implementation of a hybrid work environment related to changes in the manner employees work, frequencies of breaks, social connection and distancing, and transition of employees from temporary home work to permanent home work. It is important for individuals who have a history of related injuries (such as musculoskeletal disorders) and other disorders to seek the assistance of a certified professional ergonomist. With planning, consideration, and training, employees can continue to work productivity and safely in the hybrid work environment.

References

[1] World Health Organization (WHO) and International Labour

Organization (ILO), 2021. Preventing and mitigating COVID-19 at work. Policy Brief. Retrieved 2 Feb 2022 from www.who.int/publications/i/ item/WHO-2019-nCoV-workplace-actions-policy-brief-2021-1. [2] Fernandez, J.E. and Marley, R. J. (2013). Applied Occupational

Ergonomics: A Textbook, Fourth Edition. Society for Industrial and Systems Engineering Press, 2013. [3] Putz-Anderson, V. (1988). Cumulative Trauma Disorders: A manual for musculoskeletal disease of the upper limbs. Taylor and Francis, London and New York.

Anand Subramanian (anands@jfa-inc.com) is a principal at JFAssociates Inc.. He holds a Ph.D. and masters degree in industrial engineering from the University of Cincinnati, Ohio, is a certified Six-Sigma Black Belt, a certified professional ergonomist, an associate safety professional, and an OSHA-30 certified professional. For more information visit jfa-inc.com

Brandy Farris Miller

(bmiller@apexergonomics.com) is a principal at Apex Ergonomics. She holds a Ph.D. in business organization and management and master's degree in industrial engineering with an emphasis in applied occupational ergonomics. She is a certified professional ergonomist, certified Six-Sigma Black Belt, an OSHA authorized 10/30 hour general industry outreach trainer. For more information visit: apexergonomics.com/

Jeffrey Fernandez (jf@jfa-inc.com) is the managing principal at JFAssociates Inc.. He holds a Ph.D. in industrial engineering from Texas Tech University, is a registered professional engineer and a certified professional ergonomist. For more information visit jfa-inc.com

Advertisement

Complete Metrology Solutions

for contact lenses and IOL's