EXEPOSÉ | 11 SEPT 2020

SCIENCE

We built this city

29

Elinor Jones, Online Lifestyle Editor, examines how diseases thrive on the expansion of urban living

A

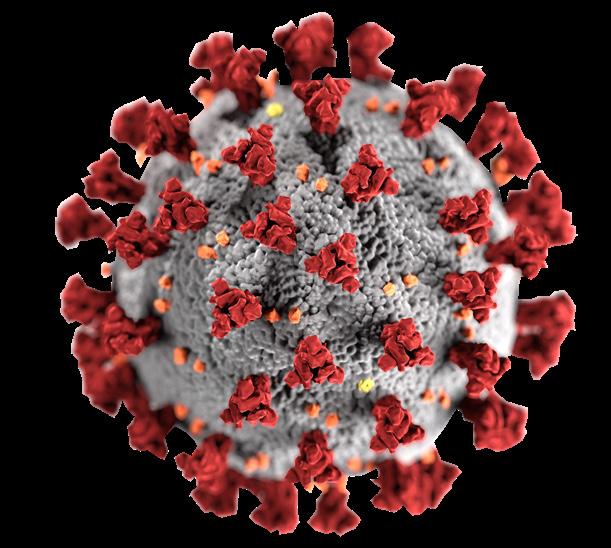

S lockdown eases, the sudden influx of visitors to rural areas is a cause for concern for public health and local authorities in the management of coronavirus. However, densely populated cities across the world have been the areas hardest hit during the pandemic, shining a light on the complexities of containing the spread of a virus amidst confined accommodation, busy high streets and on public transport. The coronavirus pandemic has demonstrated the need for better urban planning, in order to prevent cramming, in the hopes of fitting as many homes into the smallest area possible, and the need for more stringent hygiene procedures in public places, such as on the daily commute and in our schools. The virus’ hold over cities and towns is not a modern, 21st century phenomenon brought on only by increased international travel and fast transport. History has repeated itself time and again in the exponential spread of infec-

tious diseases through urban areas, from measles to the Black Death, with such illnesses potentially arriving in human populations earlier than once thought; evident during the emergence of modern-day cities.

Densely populated cities across the world have been areas hardest hit during the pandemic Crossing over from cattle to humans in 500 BC, 1500 years earlier than previously estimated, measles is thought to have become prevalent once cities first started to emerge; needing a dense enough population to wreak havoc upon. Although in recent decades vaccination drives have almost eradicated it from circulation, measles is still one of the world’s most infectious diseases affecting humans, causing

acute respiratory illness, a rash and malaise as a result of a single-stranded RNA virus, which sequencing has shown to be much older than initially thought. Transmitted through contaminated droplets, confined spaces and stagnant air may become highly infected with measles, meaning it is likely that the emergence of crowded cities and towns provided a breeding ground for the infection. It is estimated that the virus needs between a quarter of a million and half a million people within an area to maintain it in circulation. Even before the beginning of the Industrial Revolution, cities played a major role in the epidemiology of infectious diseases. A considerable factor in the spread of the Black Death in the 14th century was the mass movement from rural areas to urban areas, meaning towns became bustling, housing became crowded, and virus levels within the population prevailed. John Snow discovered the link between cholera and con-

taminated water when deaths from the disease rapidly increased in the mid-19th century due to overpopulated areas accessing a limited water supply. In 2020, some urban areas have had to enter a second lockdown with new restrictions placed on residents where COVID-19 cases have spiked (such as local authority housing in Melbourne, Australia) despite most of the country enjoying the freedom of few coronavirus cases.

There is a need for a deeper understanding of the impacts of modern city life New evidence from genetic studies of the history of measles, as well as current anecdotal information and case numbers from coronavirus, show the need for deeper understanding of the

impacts of modern city life. Comprehension of how people live, work and move in and out of our cities and towns is essential in order to control infectious diseases and prevent another historic pandemic. Over the next 30 years, urban populations are set to expand to a level where almost all of the world lives in cities and towns, where currently half of inhabitants do. Infectious diseases such as lower respiratory tract infections, diarrhoea and HIV/AIDS are a major concern for lower income countries, whilst chronic illnesses like heart disease, obesity and stroke are increasing in prevalence in higher income countries. Whether diseases are spread through close contact and poor quality of housing and sanitation or through lifestyle changes that result due to living in urban areas, careful consideration of the health needs of city populations is crucial to prevent ill health in the future. Images (top to bottom): Unsplash; KTEditor, Pixabay

Moving with porpoise

I

Bryony Gooch, Editor, details new discoveries in dolphin behaviours

F you were not aware of just how intelligent dolphins are, here is another example of their braininess. Scientists have observed that dolphins inhabiting Shark Bay have learned an unusual hunting strategy called “shelling.” Dolphins trap fish inside the empty shells of giant snails, bringing the shells to the surface to shake them out into their open mouths. This is the second-known instance of dolphins using tools to help streamline their foraging. In 1997, bottlenose dolphins were found wearing marine sponges over their beaks for protection when foraging for fish along the sea floor. Additionally, this technique not only proves that dolphins have an elevated method of hunting, but that they learn from their peers. Sonja Wild, who conducted the research for her doctorate at the University of Leeds, expressed her surprise as “dolphins and other toothed whales tend

to follow a 'do-as-mother-does' strategy for learning foraging behaviour." The researchers, having observed the quick nature of this shelling technique, used a social network analysis to discover how the strategy came to be learned. This involved looking into social network, environmental factors, and genetic relationships and drew a conclusion that rather than this skill being passed on generation-to-generation, it has more socially learned roots. Therefore, this approach to survival could be considered a cultural behaviour.

The effect of the high temperatures on the ecosystem killed off many gastropods It is believed that this shelling technique, which began to receive attention ten years ago from scientists,

has become more frequent since the marine heat wave off Western Australia in 2011. The effect of the high temperatures on the ecosystem killed off many gastropods. Wild commented that they thought the dolphins took advantage of "the die-off." Indeed, it was in the next season that the use of the technique increased, making it possible to understand how young adult dolphins learned to 'shell'. This evidences the marine mammals' ability to adapt to environmental changes. Considering the effects of climate change, it is interesting to observe dolphins reacting to the changes in their ecosystem to survive in exacerbated circumstances. This new discovery of learned behaviour adds to a growing comparison between dolphins – cetaceans more generally in fact – and great apes. Michael Krutzen, of the University of Zurich, pointed out that both are “long-lived, large-

brained mammals with high capacities for innovation and cultural transmission of behaviours.” This adds to a large body of evidence of dolphins' intelligence. Already, their behaviour has shown them to be quick learners and talented mim-

ics, but they also develop self-awareness; problem-solving skills such as innovation and teaching ability; and a degree of emotional intelligence; displaying such emotions as grief, joy and playfulness. Images (top to bottom): Paige Page, Pooya - both Unsplash