9 minute read

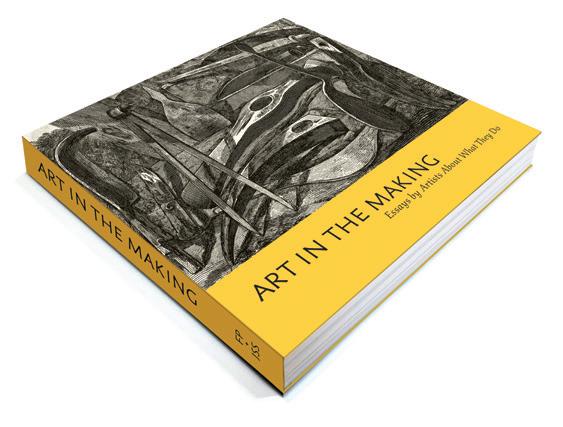

Art in the Making J

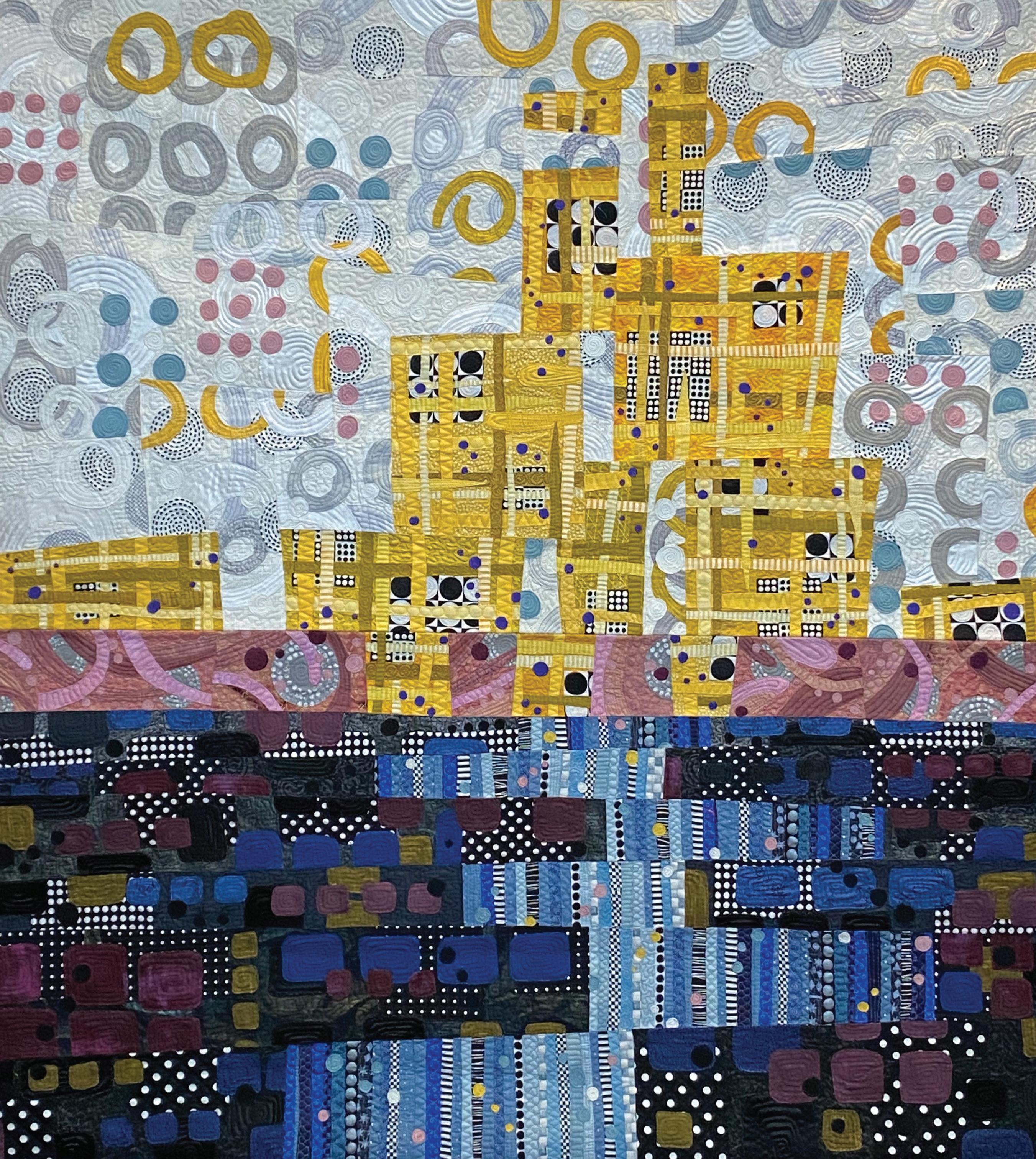

une through August, 2023, Evoke Contemporary will host a group exhibition for a selection of the work and writings of the artist-essayists who contributed to the new book Art in the Making: Essays by Artists about What They Do.

The aim of the exhibition

This summer we are pleased to showcase a wide range of the works of the contributing artist-essayists who have made this book a rich resource of practical first-person narratives. Evoke Contemporary, together with us, the book’s publishers, are assembling and curating a diverse selection of artwork throughout the gallery, showcasing many examples of the works discussed in the book. Each work will be accompanied by wall text excerpted from its creator’s essay.

The origins of the book

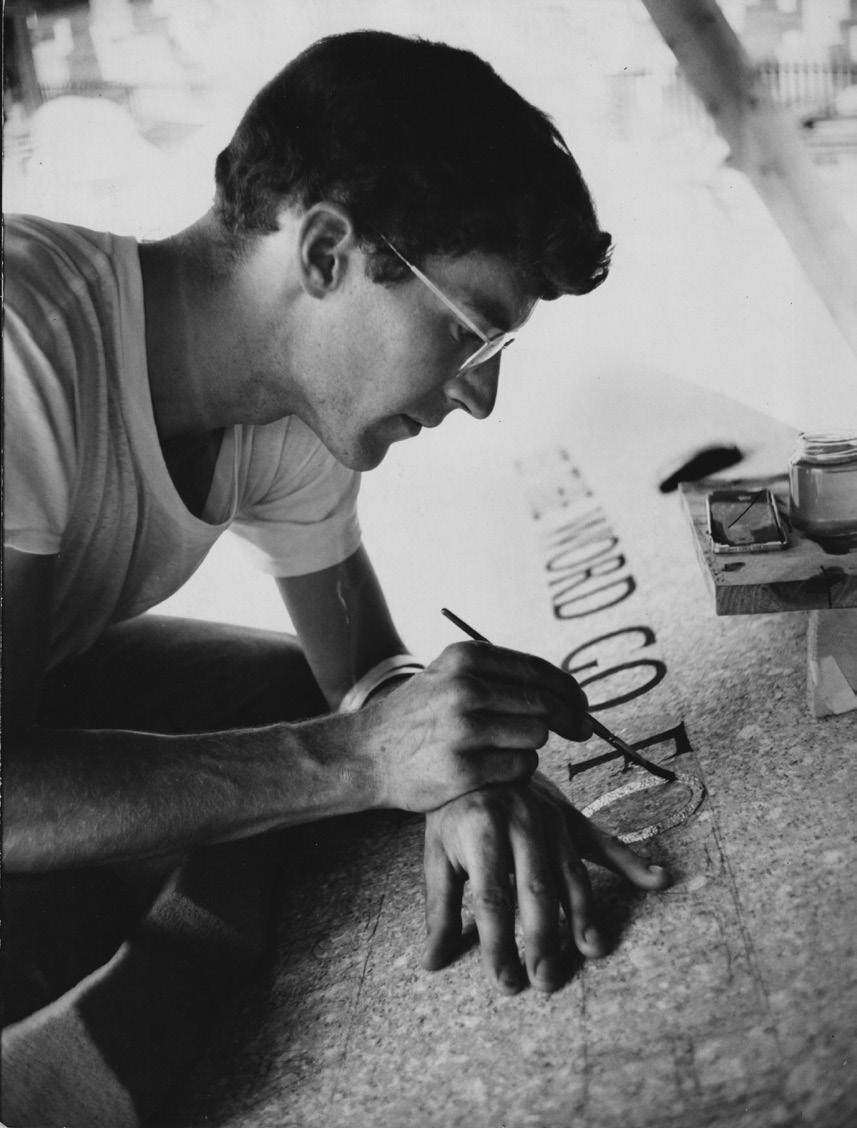

The book grew out of the long artisanal tradition within the family of its copublishers, the artist brothers Christopher and Nicholas Benson. Their grandfather, John Howard Benson, purchased the John Stevens Stone Carving and Lettering Shop in 1927. The shop was founded in 1705 in Newport, Rhode Island and was owned by the same family for 220 years; it produced some of Colonial America’s finest gravestones and other stonework. Early in the 20th century, the new partners of the shop published numerous books and pamphlets on the practices and philosophies of art and craft. Theirs was a local, American tributary of the Arts and Crafts movement, which had been launched in Britain in the 19th century by John Ruskin and William Morris.

Each of the shop’s owners—Benson, Arthur Graham Carey, and Adé Bethune—contributed to these publications. Others whose writing appeared in the series included the English sculptor, typographer, and letterer Eric Gill, as well as Ananda K. Coomaraswamy, the Sri Lankan art historian and curator of Asian arts at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts.

This collection of essays continues that tradition. It has been assembled, edited, and designed by Christopher Benson—a painter, arts writer, book designer, and publisher living in Santa Fe—and co-published by his company, The Fisher Press, and The John Stevens Shop. Christopher’s brother Nick, a renowned letter carver and a 2010 MacArthur Foundation Fellow, is the current proprietor of the Stevens Shop, and both are grandsons of John Howard Benson.

“Why does a modern young man practice the exacting, antique art of carving rocks? At thirty-six, Benson does it for love, money, and the ‘the old pleasure center—the sexual rush’ that comes with creating or contemplating something of rare beauty. He is quite serious about the Pleasure Center Principle, citing neurologists who say that both aesthetic excitement and sensual feeling occur in the same part of the human brain. He also quotes Veronese: ‘Given a large canvas, I enriched it as I saw fit.’”

Why make a book about what artists do?

Academic and critical discourses about artworks and art movements can be quite informative, but can also seem remote and lofty to the layperson, written in language that feels distant from our daily lives. Also, most such writings are created by people who do not themselves make art. They may be critics, historians, or trend-conscious hangers-on to the fashionable carnival of the art market—but they are seldom artists.

Our aim in assembling this collection of essays was to offer the reader, and the viewing public, an entirely different perspective: one not so dependent on the interpretations of outside commentators, but that instead would present, direct and unfiltered, the ideas, methodologies, and creative drives of the artists themselves.

Practicing craft that exists in so many forms, all of which are connected by a common methodoligical thread, and all under threat of extinction form technological change and globalization, is a weight that I do not carry lightly. I feel driven to produce finely crafted work in an aesthetic sense, but also to preserve the skills and traditions of such a noble craft, and to be able to pass them on to the next generation of young blacksmiths.

The deeper I go into the process (of creating), the more I am listening and the less I am speaking. It tells me what it needs. This “It” is what informs and guides the craft. This happens through familiarity with my materials— but also, importantly, through unfamiliarity: letting go of preconsceptions, my own fickle likes or dislikes, and any identification with what I’ve done in the past, as I remain open to what is unfolding.

—Carola Clift

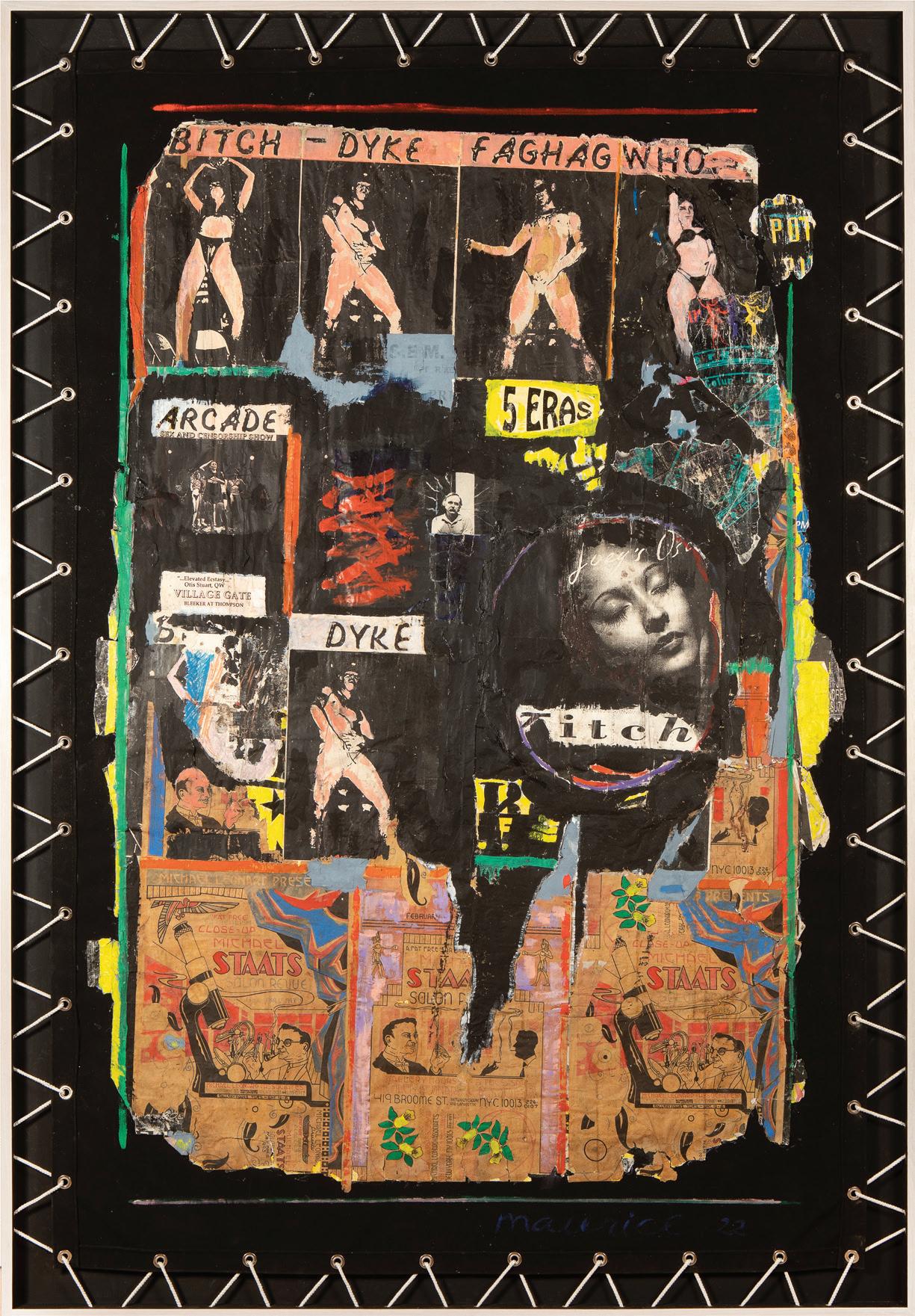

Collage and Abstract Expressionistic painting are inventions of the twentieth century that have formed my aesthetic and my structural process. Creating and controlling accident, combining historical idioms into heterogeneous imagery and expression are my driving visual concerns. For me painting is a conflict between analysis and intuition, control and surrender, desire and love.

—David Frazer

—I woke up to “It Paints”— that out-of-body experience where some inexplicable force takes over the production. Fellini described it this way: “When I direct, a mysterious invader takes over and directs the whole film for me.” Philip Guston put it like this: “You go into the studio and everybody is there — your friends , the art writers and the museum people and you’re just there painting. And one by one they leave until you’re really alone. Then Ideally, you leave.” It paints.

—Patrick McFarlin

After all these years, every new piece I make feels like a plunge off a cliff where knowledge, certainty and security are gone. Although I am not religious, I have come to understand that creativity in the arts is a pure act of faith. As I leave the realm of the unknown to f ollow the piece where it wants to take me there is literally nothing to hang my hat on. It is surprising to discover just how much faith art-making requires. It’s a number that encompasses both zero and infinity.

—Judith Schaechter

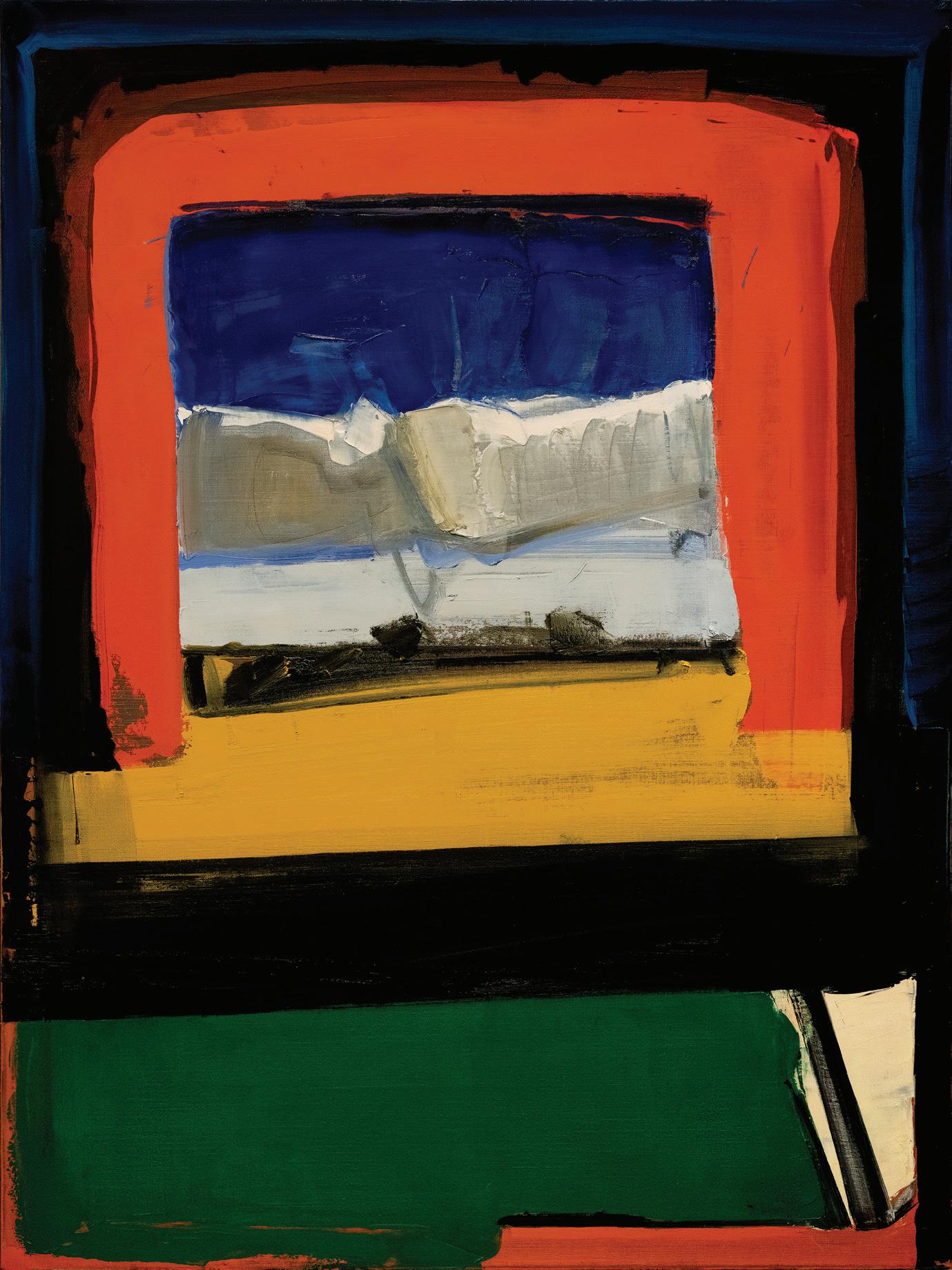

My compositions and palettes evolve during my experiments in the studio, conflating and referencing many historical movements and tendencies from Modernism to Abstract Expressionism, Color Field to Minimalism and beyond—creating my own language out of many forms of abstraction. I try to open up visual possibility, painting expansively, regardless of the size of the visual field, laying down broadly described areas of color, painterly gesture, defined contour, combinations of texture, scratch and scribble, and geometrically defined hard edges. My paintings layer and illustrate a visual history of the medium’s evolution while simultaneously concealing it, transforming the image into something altogether new.

Much of my creative process begins with a sudden movement or recognition. I’ll be walking down a sidewalk whe some tiny detail of form, a subtle movement, or an abstract sensation grabs my attention with an unmistakable poke to my gut. I’m compelled to stop, look, and capture it, ideally before my mind gets busy interpreting or labeling—as if I’d encountered a bubbling spring and made a connection between the everyday world and a hidden aquifer deep beneath.

—Will Clift

We also hoped to showcase as wide a diversity of types of art as possible. Another characteristic of the art criticism of our time has been the tendency of critics to elevate one form, genre, or medium over another as “the latest” or currently “the most important.” We passionately believe that there is no such thing as a right or best or most important way to make art. There are only greater or lesser examples of any given kind.

It has been accepted for some time that the “fine” arts are no longer limited to painting and sculpture, as they were for so long. But living as we do in an age in which handmade things are becoming vanishingly rare, we can also reasonably add any practice done by hand with care and at a level of mastery. In fact, a great many ancient artifacts now found in museums and regarded as works of high art were, when created, the products of a fully mostly utilitarian sort of craft.

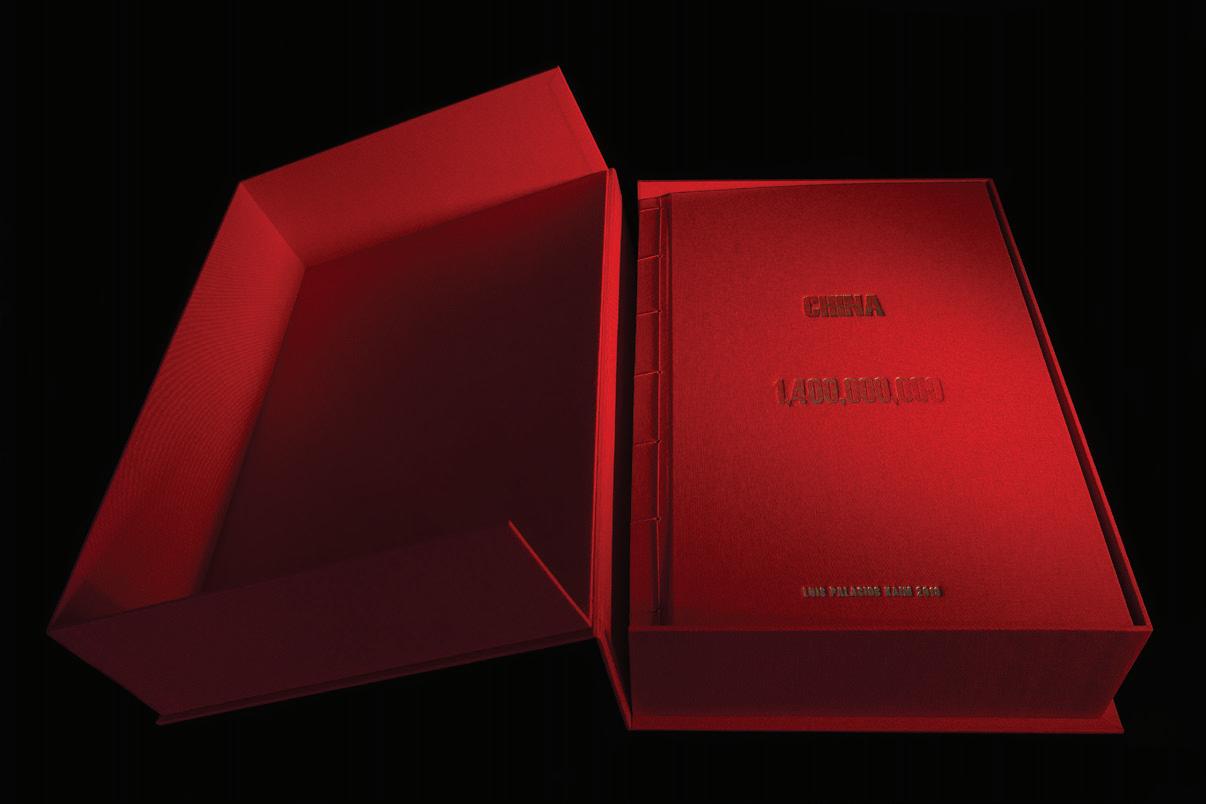

What is considered art today therefore includes a far wider range of thoughtfully made things, from ceramics and furniture to musical instruments, handmade books, clothing—even cooking. It includes the disciplines of music, dance, and theater, of poetry and prose, and the many technological methods a contemporary maker might bend to a more handcrafted ethos. The camera, computer, LED screen, and digital printer can all be the tools of artists, as much as the pen, brush, and chisel, the violin or the saucepan. In short, it is no longer the tool that qualifies any given practice as an art, but the skill and understanding of the person who wields it. That kind of direct, practical understanding is the sole focus of these essays.

We feel that one of the most pleasant surprises about the texts presented in Art in the Making: Essays by Artists about What They Do is how down-to-earth and relatable the drives and motives of artists can be. Far from dwelling in remote ivory towers of abstruse philosophy and theory, artists are, for the most part, much like anyone else: they have to earn a living; they have spouses and children, houses to clean, lawns to mow. But they’ve chosen a path in life that takes a rather unconventional approach to looking at, talking about, and reflecting on the qualities and characters of the wide range of experiences shared by all humans. There is no reason to be intimidated by what they do.

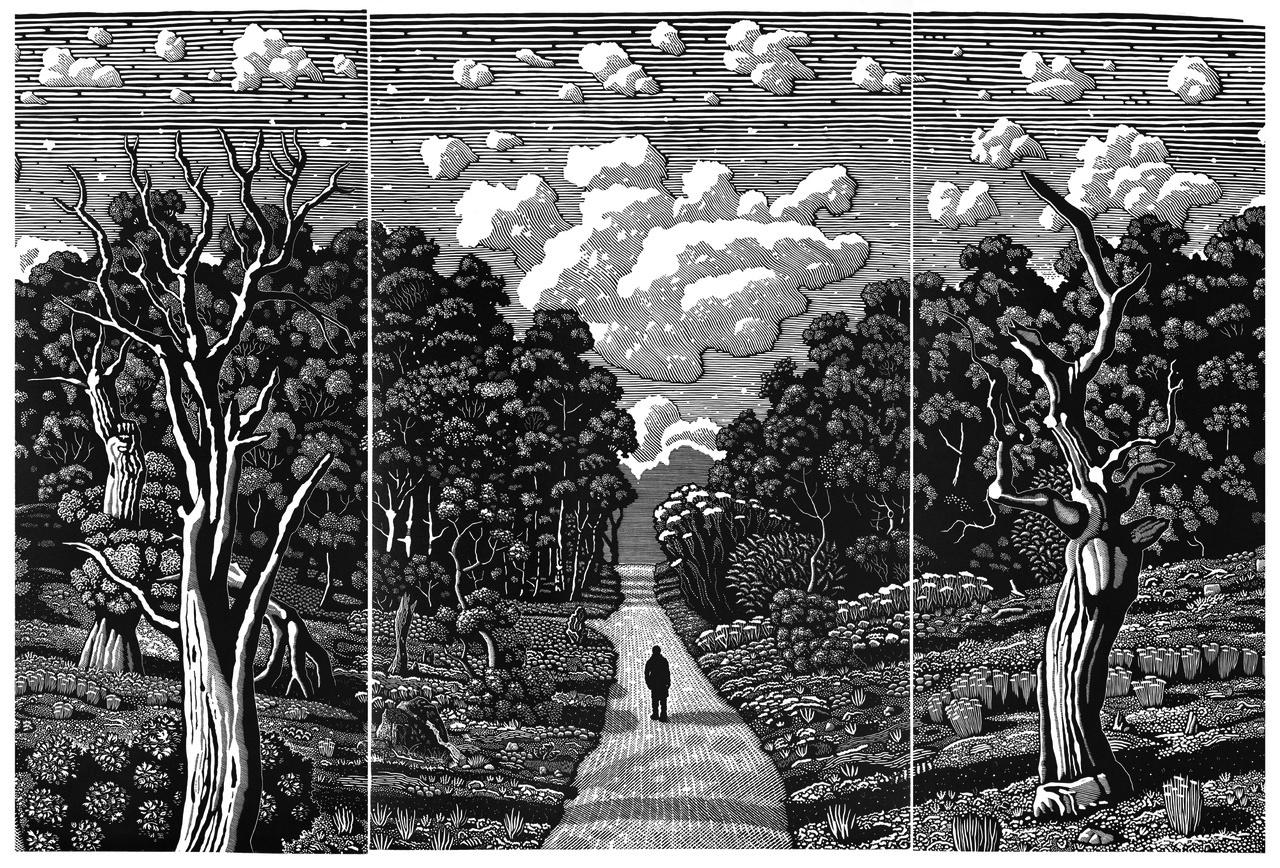

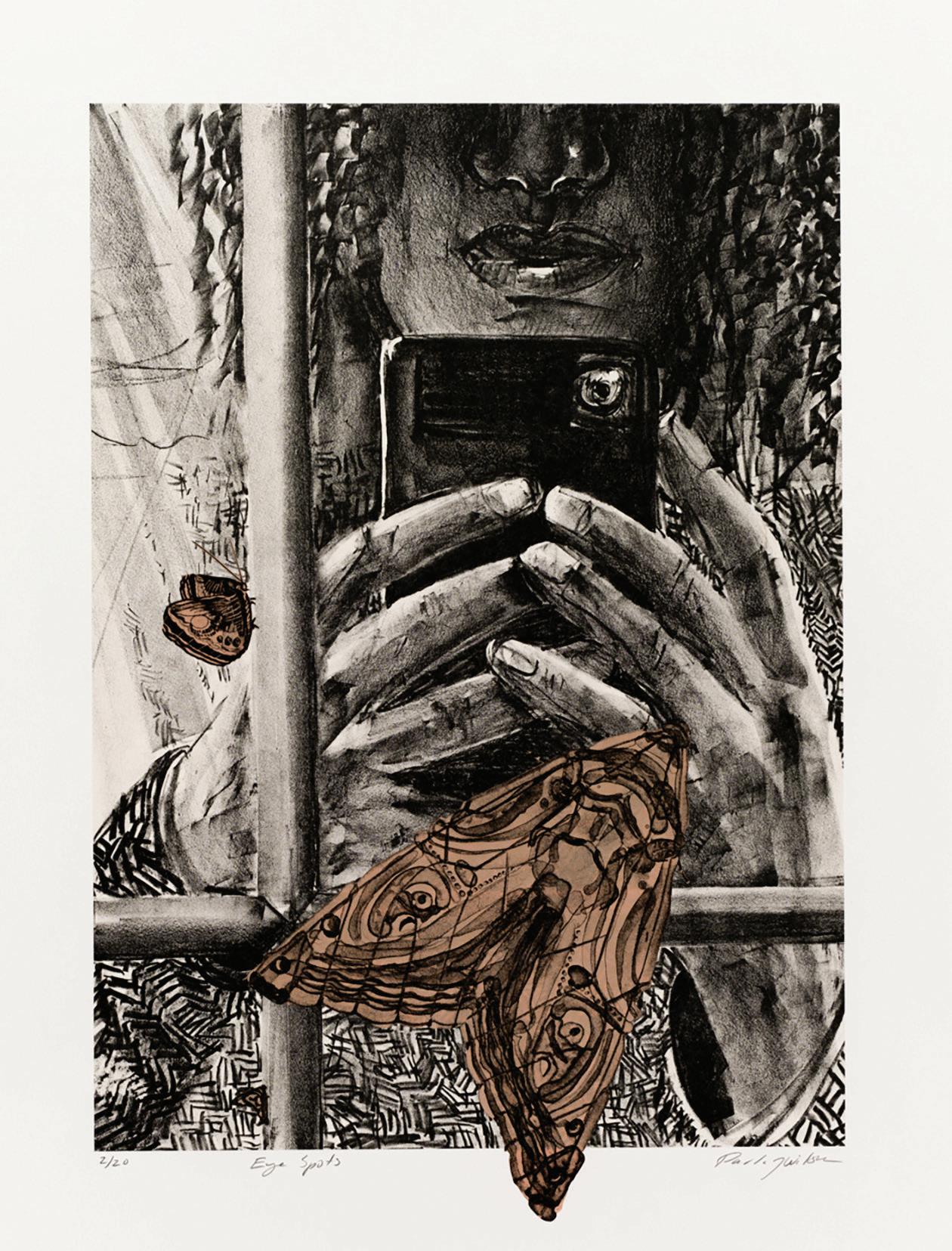

The exhibition at Evoke presents a selection of 60 of the artist-essayists’ work. Paintings, sculpture, ceramics, furniture, photography, conceptual art will be on view until August 19, 2023. In addition to the essays and artwork, there will be supporting events taking place throughout the duration of the show. Contact the gallery to receive updates on all related lectures, demonstrations and performances taking place throughout the summer.

There’s no clear benfit to spending your life as an artist. It’s a ridiculous process to participate in: a real roller coaster ride. But I think if you approach it in a scientific spirit—where there are things to discover, and that conversation with the unknown is a thing you just want to involve yourself in—that becomes addictive. You’re no longer just making an image that’s recognizably yours like some fashion line; you’re after making something that’s different today from what it was ten years ago. An evolution of your own spirit takes place in the work. I always think that while you can have an idea that you want to seek as a painter—the idea isn’t where you want to end up; you want to FIND something.

—Michael Scott

I see myself as an excavator. The substance and final imagery in my work can be somewhat schizophrenic, varying as it does from a kind of psychological landscape to portraiture, albeit of the darker kind, but the process of my work is always the same,. I find myself discovering the painting through process and through allowing any elements of chance, accident and circumstance to dictate the revealing of the imagery therein. It is often only in restrospect that I understand, or see, the personal emotional relevance of any particular painting.

So, the effort, the struggle, the challenge—that is the art. Painting is my craft.

As my most favorite thing to do, the process of painting seeps into every part of my life and it is what makes me a whole person. One of my favorite people in the world was my aunt, Sister Eleanor McNally. She and I talked about the concept of a ‘calling’ many times. Although I am not a religious person, being an artist is my calling; she and I both agreed upon that. So why do I do it? Because it’s what I am.

Painting gives me the freedom to explore my own mind and forget about the world’s crushing problems. And when—after I am done—I realize that a particular painting has not turned out well, the trashcan is at my feet. It turns out that watercolor paper tears in half very easily, with a satisfying sound. And so, I begin again . . .

I have always had a painterly approach, with brush and knife marks clearly evident in my surfaces. The slick stylizations of much of the work proliferating today across the internet and at the art fairs and galleries does not interest me much. We’re so neurotic about artistic novelty now that much of the contemporary art of the past few decades feels quite superficial to me. Somewhere along the line, painting especially became more of a product line than the sort of probing visual poetry that first called me to this path.

There’s nothing wrong with modernity. I want to be modern too. And, if we’re honest, we don’t have a choice, do we? We live in the modern world and anything we do here will inevitably reflect it, even when we try to hide from it by re-inventing the past. But I often think how Edouard Manet ( a leading innovator of early Modernism) was so startlingly contemporary in his own time while yet tipping his hat to the masters who had preceded him. That was part of what made his work so rich and complex. For me too, new works that can’t comfortably retain some of the hoary residue of painting’s past offer a pretty thin soup; I just find myself wanting more to eat.

—Christopher Benson

Krista Elrick, The Conflict of new economies on the Ivory-billed woodpecker (Campephilius Principallis) and the trees that support them, archival pigment