15 minute read

Scientific

Raising Awareness about Extreme Rainfall through Gamification

Due to climate change, extreme rainfall events will occur more frequently in Amsterdam in the future. At the moment, awareness about the damage these extreme events could cause is minimal, and because water management during extreme rainfall requires a shared approach, “the tragedy of the commons” applies to the issue. In this study the influence of gamification and persuasive design on citizens’ awareness about the topic was investigated by testing the game “Heroes of Rain”. Before the game, the players participated in a survey; the same survey was carried out after they had played the game. The results were compared with the experiences of testing the game and in-depth interviews. While testing the game the players started a conversation, and their answers in the second survey were significantly different and suggested a higher level of awareness. This is in line with the theory of the Game-Based Learning Elevation Model (GEM) which suggests that information exchange after playing games raises awareness.

Advertisement

awareness, gamification, natural hazards, extreme rainfall events, persuasive design, citizen empowerment Dymphie Burger (EGEA Amsterdam) Co-authors: Irati Santxo, Jeffrey Gyamfi, Almar Mulder

1. Introduction

Due to climate change, societies are getting more vulnerable to extreme weather events. However, exact effects differ at a regional scale (IPCC, 2014). In the Netherlands, the amount of precipitation has increased by 21% from 1906 until 2007, and the intensity of rainfall has raised as well (PBL Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency, 2013). This is supported by seven out of the ten most extreme showers, since 1951, having occurred in the last 20 years (Kluck, et al., 2013). Due to the amount of impermeable surface in Amsterdam, the sewerage has to handle most of the rainwater. The sewerage is adjusted to roughly 20 millimetres per hour (Kluck, et al., 2015) and therefore not able to handle a shower with a higher intensity. The excessive rainwater accumulates on the streets, resulting in water nuisance or even damage. However, awareness about these extreme rainfall events is minimal among the citizens of Amsterdam. The minimal management of extreme rainfall (i.e. natural hazards) is considered a “tragedy of the commons”, as extreme rainfall damages public properties and therefore affects all people. However, due to public ownership, nobody feels responsible to prevent the damage (Tompkins and Adger, 2004). At the moment, gamification is becoming a more and more popular method to raise awareness and engage people (Thiel, 2015). It is used as well to influence behaviour, enhance motivation and improve engagement by applying game metaphors (Marczewski, 2013). An example of gamification that has been used for a long time are grades in schools, or parents rewarding children for preferred behaviour (Nicholson, 2014). In this paper, gamification will be analysed together with persuasive design, a method which attempts an action or behaviour (Fogg, 2009), i.e. becoming aware of the extreme rainfall events. Therefore, the aim of this study is to test how these methods influence awareness and to try to find a way to raise awareness with a simulation game. This game will be used by Amsterdam Rainproof, a project of the governmental organisation that takes care of the whole water cycle in the municipality of Amsterdam. The research question is:

Figure 1: The 7 doors to behavioural change Source: Robinson, n.d., p.4

How does gamification influence the level of awareness and engagement of citizens of Amsterdam in the “commons’ problems” of extreme precipitation? Awareness in this paper is the knowledge obtained from information or experiences that heavy rainfall events in Amsterdam will occur more frequently in the future. Engagement means in this research that the citizens also take action by, for example, “rainproofing” their houses. The “tragedy of the commons” can be defined as a problem where nobody thinks about the limits of public space (also called commons). The public tries to get as much profit as possible from that space but exhausts it at the same time (Hardin, 1968).

2. Related work

2.1 Tragedy of the commons

The “tragedy of the commons” can be applied to natural hazard management: Everyone benefits from contributing to risk management, but this contribution does not create direct gains for the individual (Tompkins and Adger, 2004). However, when a natural hazard occurs, a big part of the community experiences the losses. These problems can mostly be prevented with governance of the commons, by implementation of boundary rules on who can use them, how much and when (Ostrom, 2008). Thus, community engagement can reduce vulnerability and make the community more resilient against natural hazards (Weichselgartner and Obersteiner, 2002).

2.2 Gamification and awareness

By using gamification in behavioural change, desired behaviour is rewarded as in a game. Rewarding mechanisms in the game encourage the behaviour a player should have. If the learning process has been gamified right, it can be enhanced and people will become more aware (Lawley, 2012). Gamification as a method for raising awareness can also be described in the “seven doors” model (Figure 1). The model shows the optimal path from a state of not being aware to long lasting behavioural change (Robinson, 2012). To be successful, all seven steps must be completed. A game must show all elements, from providing knowledge about a problem, explaining how a player could act in real life, to showing that it was a success. The positive feedback loop the model creates will cause the change in behaviour (Liu, et al., 2011). The model is not a closed circle, because the already changed behaviour of the player cannot be changed back. However, a player can convince others to play, which means that they are an “educator”, and more people will become aware and engaged (Sayers, 2006).

2.3 Persuasive design and awareness

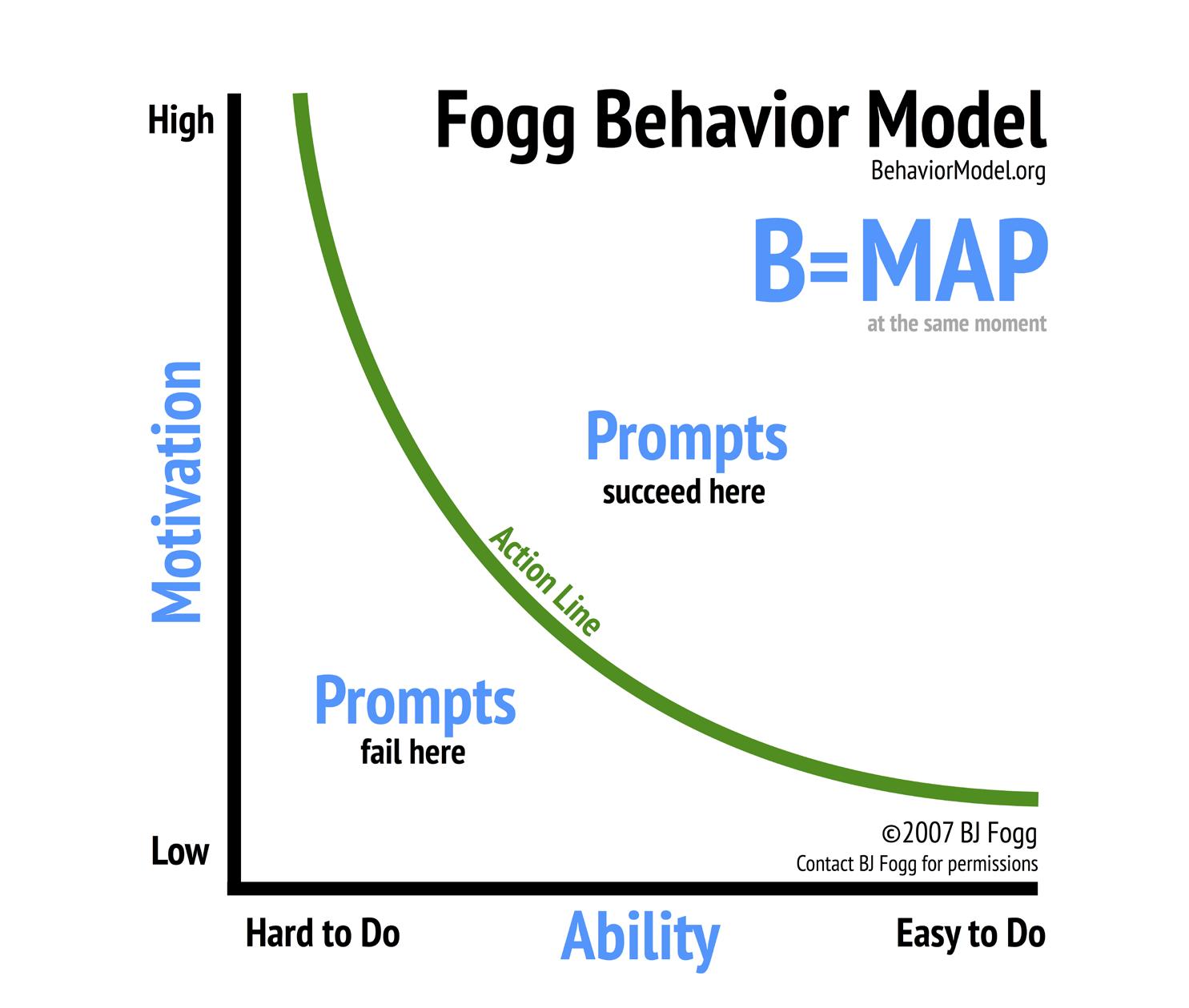

Gamification does not work on its own in order to get the desired effect. The game must also include good game design (Lawley, 2012). Persuasive design is a way of designing that can influence people’s behaviour (Fogg, 2009). The Fogg Behaviour Model (FBM, Figure 2) includes three components: motivation, ability and triggers to reach a target behaviour. According to the study, people mostly have a low level of ability and motivation, and the task for designers is thus to increase these factors. Most of

Figure 2: Persuasive design according to the FBM model Source: Fogg, 2007

the time, it seems that making the behaviour less difficult (increasing ability) increases the behaviour performance the most. The third factor is the trigger, which is a spark, facilitator or a signal that, when timed well, calls to action (Fogg, 2009).

3. Methodology

There were two surveys carried out among Amsterdam’s citizens, survey A and survey B. Survey A was carried out and analysed during the building of the game about awareness and engagement in heavy rainfall events. This survey had 97 respondents in total. Of these, 76 of the respondents surveyed were approached via Facebook groups for people living in Amsterdam, 10 respondents were working at the institute and 11 respondents were approached at an event for creative and innovative start-up companies (FabCity Campus). The game was tested on the 10 respondents working at the institute and the 11 respondents at the FabCity Campus event. These 21 players will be called the “test audience”. After playing the game the test audience filled out survey B. In addition to the survey, four more in-depth interviews were done, those people were approached via Facebook groups for people living in Amsterdam. The samples are convenience samples. The sample of survey B (the test audience) is included in the sample of survey A. The majority of the survey’s participants were female, high-educated tenants living in Amsterdam, and the average age of the survey’s participants was 29 years. The surveys were analysed using Microsoft Excel. In order to measure the awareness before and after the game, a one-tailed t-test was carried out with equal or unequal variances. The type of t-test was dependent on the outcome of a previously done f-test.

4. Results

32% of the respondents of survey A thought that it rained more often and more intensely, 75% had never heard of the Amsterdam Rainproof, and 73% had never had any damage from heavy rainfall events. To the question “How much nuisance do you think extreme rainfall events cause?”, 70% replied with “no nuisance at all” or “not so much nuisance”. Besides that, 76% had never taken rainproofing measures before. Three of the interviewees did not own a house and did not hold themselves responsible for rainproofing their houses. However, they would like to have more information about what they could do as tenants to make their houses more

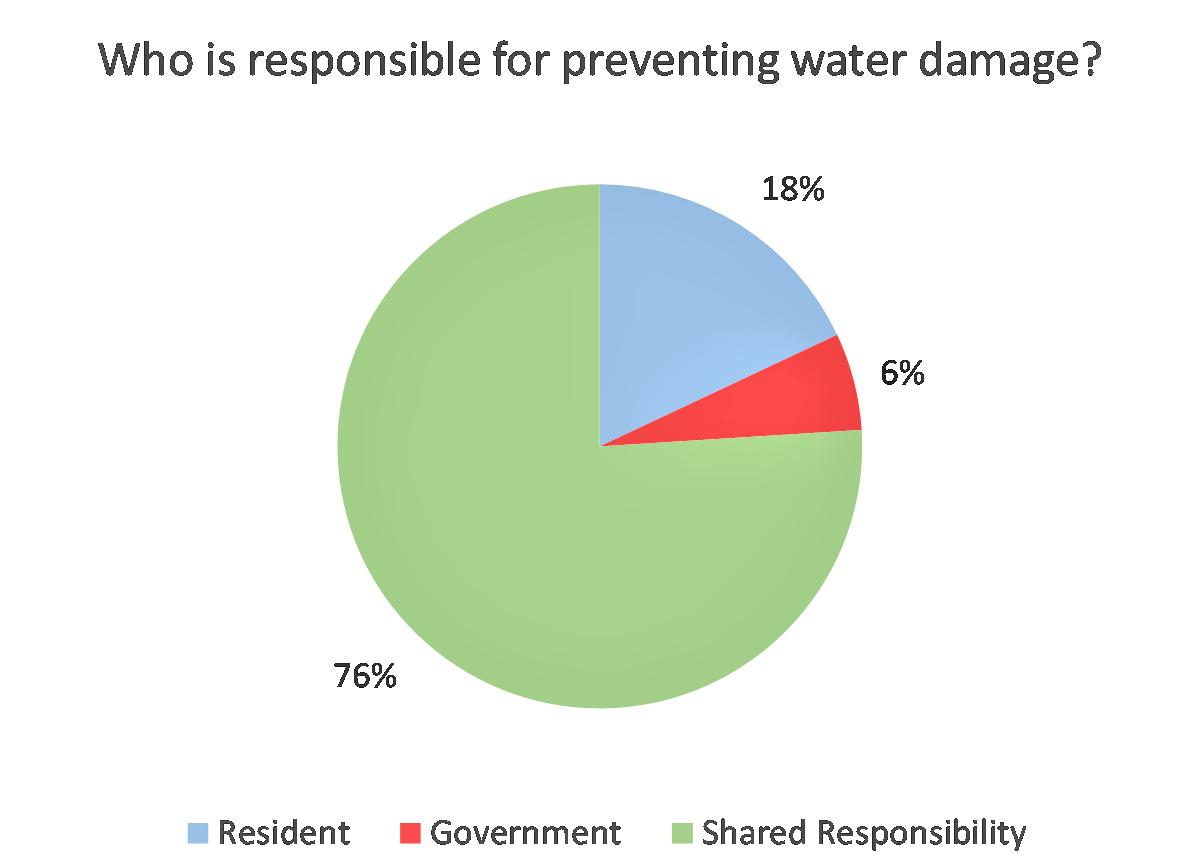

Figure 3: Answers to the question “Who is responsible for preventing water damage?” before playing the game Source: Author’s own

rainproof. The respondent that owned a house had had a damage before and thought rainproofing houses was a shared responsibility. Secondly, this respondent said that he lacked knowledge about rainproofing his house. The aim of the game is to rainproof the player’s virtual house in five minutes, which they can do by answering quiz questions about rainproofing, climate change and Amsterdam Rainproof or without questions. Beside the quiz, the players can try to install measurements to their property in the game, such as buying a barrel or swapping tiles in the garden for grass. After and during the testing of the game, all players started a conversation, either with their test partner or with the researchers about the topic of a water resilient city. After the testing of the game, survey B was done with the test audience. Three questions of the survey were the same

Figure 4: Answers to the question “Who is responsible for preventing water damage?” after playing the game Source: Author’s own as before the testing, these were: “How much nuisance do you think extreme rainfall causes?”, “Who do you think is responsible for preventing damage?” and “Would you take measures to make your house more climate resilient?”. After playing the game, 60% of the respondents chose “no nuisance at all” or “not so much nuisance” when asked “How much nuisance do you think heavy rainfall events cause?”, which is a decline of 10 %. However, the t-test for unequal variances showed a p-value of 0.32, which means that the decline is not statistically significant at a 95% confidence level. After playing the game, 52% of the respondents said they wanted to take measures to make their house more water resilient. This number has been compared with the percentage of respondents that had taken measures before already (21%). A t-test for equal variances showed a p-value of 0.08, which means that this increase is not statistically significant at a 95% confidence level, although it is significant at a 90% confidence level. 33% of the players said the residents were responsible for water damage, which is an increase in comparison with the before-survey (see Figure 3 and Figure 4). The p-value for the t-test for equal variances was 0.03, which means that there is a significant increase at a 95% confidence interval.

5. Discussion

The game Heroes of Rain tries to tackle the problem of the “tragedy of the commons” by adding boundaries and providing ownership rights to virtual houses. Giving the player ownership rights can make them feel more responsible for their land (Marczewski, 2013). Secondly, the seven doors model has been applied as the game informs the player and shows them that making their house more climate resilient pays off by using reward-strategies (Robinson, 2012). The game is a persuasive game, and the aimed-at behaviour is made easier (ability factor of the game is high), which means that it is simple to install measures (Fogg, 2009). The trigger that is needed to make the player take action is a spark in the user experience. The spark is the trigger that raises motivation in this case. For the game, the spark is fear, because the game works towards a cloudburst as severe as the cloudburst in Copenhagen of 2011, which resulted in 1 billion euros worth of damage.

In this research, awareness was measured by doing surveys before and after playing the game. The surveys showed a statistically significant increase in awareness among the players. However, the sample used for this research is a convenience sample and is not representative for all of Amsterdam’s citizens due to the low respondent numbers of survey B and the underrepresented group of house owners. Nevertheless, all respondents reacted the same to persuasive games. Measuring awareness is difficult. After the game, all the players started a conversation with either the researchers or the other players. Telling each other what they have already done helps more in making people aware than telling people what they should do (Tannenbaum, 2013). Conversations are exchanges of information and therefore raise awareness (Dullemond, Van Gameren and Van Solingen, 2010). According to the Game-Based Learning Elevation Model (GEM), a serious game will meet the learning outcome, in this case raising awareness, if a player can reflect on the topic in the private world (Kiili, 2005). This means that according to this theory, the learning outcome of this game was met, and the game was successful, because the test audience started to reflect upon their own situation. Recommendations for further research are continuing testing of the game used in this study, as more measurements will make the findings more accurate and precise. Doing the same survey before and after the game, then comparing the results, can also provide more confidence in the validity of the data analysis. Nevertheless, this research could be seen as a pilot study that tests the possibility and chance of success of this method of raising awareness among citizens in Amsterdam about extreme rainfall events.

6. Conclusion

The comparison of the two surveys shows a significant increase in the feeling of responsibility of the players as homeowners for preventing water damage. There is a significant increase as well on whether the player would implement general measures. After the game, it was noticed that the players started reflecting on what they had just done in the game. According to the GEM model, the game meets its learning outcome. Based on the findings of this research, it is possible to say that this persuasive game has a positive influence on the level of awareness of the citizens of Amsterdam about the risks of extreme rainfall and possibilities for climate adaptation measures.

References

Dullemond, K., Van Gameren, B. and Van Solingen, R., 2010.

Virtual open conversation spaces: Towards improved awareness in a GSE setting. In: IEEE (Institute of Electrical and Electronic Engineers), 5th IEEE International Conference on Global Software Engineering. Princeton, United States 23 - 26 August 2010. Los Alamitos: IEEE Computer society.

IPCC, 2014. Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Core Writing Team, R.K. Pachauri and L.A. Meyer (eds.)]. Geneva: IPCC.

Fogg, B.J., 2007. Fogg Behaviour Model. [online] Available at: <https://www.behaviormodel.org/> [Accessed 20 May 2020].

Fogg, B.J., 2009. A behavior model for persuasive design. In: ACM (Association for Computing Machinery), 4th International Conference on Persuasive Technology. Claremont, United States, 26 - 29 April 2009. New York: ACM.

Hardin, G., 1968. The tragedy of the commons. The population problem has no technical solution; it requires a fundamental extension in morality. Science, 162(3859), pp.1243-1248.

Kiili, K., 2005. Digital game-based learning: Towards an experiential gaming model. The Internet and higher education, 8(1), pp.13-24.

Kluck, J., Boogaard, F., Goedbloed, D. and Claassen, M., 2015.

Storm Water Flooding Amsterdam, from a quick Scan analyses to an action plan. In: AIWW (Amsterdam International Water Week), 3th International Waterweek Amsterdam. Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2 - 6 November 2015. Den Haag: Netherlands Water Partnership.

Kluck, J., Van Hogezand, R., Van Dijk, E., Van Der Meulen, J.

and Straatman, A., 2013. Extreme neerslag: Anticiperen op extreme neerslag in de stad. (Extreme precipitation: Anticipate extreme precipitation in the city. ) [pdf] Amsterdam: Kenniscentrum Techniek. Hogeschool van Amsterdam. Available at: <https://edepot. wur.nl/312829> [Accessed 30 October 2019].

Lawley, E., 2012. Games as an alternate lens for design. Interactions, 19(4), pp.16-17.

Liu, Y., Alexandrova, T., Nakajima, T. and Lehdonvirta, V.,

2011. Mobile image search via local crowd: a user study. In: IEEE (Institute of Electrical and Electronic Engineers), 17th International Conference on Embedded and Real-Time Computing Systems and Applications. Toyama, Japan, 28 - 21 August 2011. Los Alamitos: IEEE Computer society.

Marczewski, A. 2013. Gamification: A Simple Introduction [ebook]. Seattle: Amazon Digital Services, Inc.. Available through:< http://blog.makeyourlifeagame.com/gamification‐resources/ gamification‐books/> [Accessed 26 June 2016].

Nicholson, S., 2014. A recipe for meaningful gamification. In: T. Reiners, & L. C. Wood, ed. 2014. Gamification in education and business. New York: Springer, pp.1-20.

Ostrom, E., 2008. Tragedy of the commons. In: P. Macmillan, ed. 2008. The new palgrave dictionary of economics. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. Ch.2.

PBL Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency, 2013.

The effects of Climate Change in the Netherlands: 2012, The Hague: PBL Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency. [online] Available at: <https://www.pbl.nl/sites/default/files/cms/ publicaties/PBL_2013_The%20effects%20of%20climate%20 change%20in%20the%20Netherlands_957.pdf> [Accessed 31 July 2019].

Robinson, L., 2012. Changeology. Totnes: Green Books.

Robinson, L., n.d. Changeology. An all-purpose theory of behavioural change. [pdf] Available at: <http://www.enablingchange. com.au/enabling_change_theory.pdf> [Accessed 20 May 2020].

Sayers, T., 2006. Principles of awareness-raising for information literacy: A case study. Bangkok: Unesco Bangkok.

Tannenbaum, M., 2013. Will changing your Facebook profile picture do anything for marriage equality?, Scientific American, [online], Available at: <https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/psysociety/marriage-equality-and-social-proof/> [Accessed 20 July 2019].

Thiel, S., 2015. Investigating the influence of game elements on civic engagement. In: ACM (Association for Computing Machinery), International Joint Conference on Pervasive and Ubiquitous Computing. Osaka, Japan, 7 - 11 September 2015. New York: ACM.

Tompkins, E. and Adger, W. N., 2004. Does adaptive management of natural resources enhance resilience to climate change? Ecology and society, 9(2).

Weichselgartner, J. and Obersteiner, M., 2002. Knowing sufficient and applying more: challenges in hazards management. Global Environmental Change Part B: Environmental Hazards, 4(2), pp.73-77.