Photo by Mark Oprea

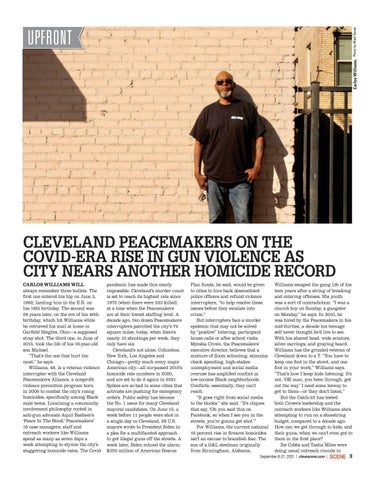

Carlos Williams.

UPFRONT

CLEVELAND PEACEMAKERS ON THE COVID-ERA RISE IN GUN VIOLENCE AS CITY NEARS ANOTHER HOMICIDE RECORD CARLOS WILLIAMS WILL always remember three bullets. The first one entered his hip on June 3, 1992, landing him in the E.R. on his 18th birthday. The second was 28 years later, on the eve of his 46th birthday, which hit Williams while he retrieved his mail at home in Garfield Heights, Ohio—a supposed stray shot. The third one, in June of 2015, took the life of his 16-year-old son Michael. “That’s the one that hurt the most,” he says. Williams, 48, is a veteran violence interrupter with the Cleveland Peacemakers Alliance, a nonprofit violence prevention program born in 2009 to combat the city’s rising homicides, specifically among Black male teens. Localizing a community involvement philosophy rooted in anti-gun advocate Aquil Basheer’s ‘Peace In The Hood,’ Peacemakers’ 16 case managers, staff and outreach workers like Williams spend as many as seven days a week attempting to stymie the city’s staggering homicide rates. The Covid

pandemic has made this nearly impossible: Cleveland’s murder count is set to reach its highest rate since 1972 (when there were 333 killed) at a time when the Peacemakers are at their lowest staffing level: A decade ago, two dozen Peacemakers interrupters patrolled the city’s 72 square miles; today, when there’s nearly 10 shootings per week, they only have six. Cleveland’s not alone. Columbus, New York, Los Angeles and Chicago—pretty much every major American city—all surpassed 2019’s homicide rate numbers in 2020, and are set to do it again in 2021. Spikes are so bad in some cities that activists are pushing for emergency orders. Public safety has become the No. 1 issue for many Cleveland mayoral candidates. On June 15, a week before 11 people were shot in a single day in Cleveland, 28 U.S. mayors wrote to President Biden in a plea for a multifaceted approach to get illegal guns off the streets. A week later, Biden echoed the alarm: $350 million of American Rescue

Plan funds, he said, would be given to cities to hire back desensitized police officers and refund violence interrupters, “to help resolve these issues before they escalate into crime.” But interrupters face a murder epidemic that may not be solved by “positive” loitering, participant house calls or after school visits. Myesha Crowe, the Peacemakers’ executive director, believes that a mixture of Zoom schooling, stimulus check spending, high-stakes unemployment and social media overuse has amplified conflict in low-income Black neighborhoods. Conflicts, essentially, they can’t reach. “It goes right from social media to the blocks,” she said. “It’s cliques that say, ‘Oh you said this on Facebook, so when I see you in the streets, you’re gonna get shot.’” For Williams, the current national 16 percent rise in firearm homicides isn’t an excuse to brandish fear. The son of a G&L steelman originally from Birmingham, Alabama,

Williams escaped the gang life of his teen years after a string of breaking and entering offenses. His youth was a sort of contradiction: “I was a church boy on Sunday, a gangster on Monday,” he says. In 2010, he was hired by the Peacemakers in his mid-thirties, a decade his teenage self never thought he’d live to see. With his shaved head, wide aviators, silver earrings, and graying beard, Williams has the grizzled veteran of Cleveland down to a T. “You have to keep one foot in the street, and one foot in your work,” Williams says. “That’s how I keep kids listening. It’s not, ‘OK man, you been through, get out the way.’ I need some leeway to get to them—or they don’t listen.” But the Catch-22 has tested both Crowe’s leadership and the outreach workers like Williams she’s attempting to run on a shoestring budget, compared to a decade ago: How can we get through to kids, and their guns, when we can’t even get to them in the first place? Ibe Cobbs and Tasha Miles were doing usual outreach rounds in

September 8-21, 2021 | clevescene.com |

9