KRAFTWERK 3-D 8:30 p.m. Wednesday, June 22 Walt Disney Theater, Dr. Phillips Center for the Performing Arts 445 S. Magnolia Ave. drphillipscenter.org $39.75-$199

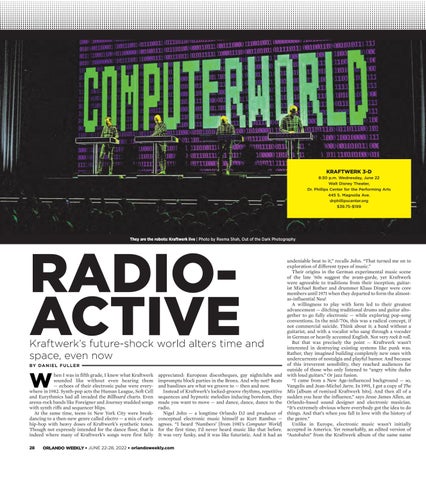

They are the robots: Kraftwerk live | Photo by Reema Shah, Out of the Dark Photography

RADIOACTIVE

Kraftwerk’s future-shock world alters time and space, even now BY DANIEL FULL ER

W

hen I was in fifth grade, I knew what Kraftwerk sounded like without even hearing them — echoes of their electronic pulse were everywhere in 1982. Synth-pop acts the Human League, Soft Cell and Eurythmics had all invaded the Billboard charts. Even arena-rock bands like Foreigner and Journey studded songs with synth riffs and sequencer blips. At the same time, teens in New York City were breakdancing to a then-new genre called electro — a mix of early hip-hop with heavy doses of Kraftwerk’s synthetic tones. Though not expressly intended for the dance floor, that is indeed where many of Kraftwerk’s songs were first fully

28

appreciated: European discotheques, gay nightclubs and impromptu block parties in the Bronx. And why not? Beats and basslines are what we groove to — then and now. Instead of Kraftwerk’s locked-groove rhythms, repetitive sequences and hypnotic melodies inducing boredom, they made you want to move — and dance, dance, dance to the radio. Nigel John — a longtime Orlando DJ and producer of conceptual electronic music himself as Kurt Rambus — agrees. “I heard ‘Numbers’ [from 1981’s Computer World] for the first time; I’d never heard music like that before. It was very funky, and it was like futuristic. And it had an

ORLANDO WEEKLY ● JUNE 22-28, 2022 ● orlandoweekly.com

undeniable beat to it,” recalls John. “That turned me on to exploration of different types of music.” Their origins in the German experimental music scene of the late ’60s suggest the avant-garde, yet Kraftwerk were agreeable to traditions from their inception; guitarist Michael Rother and drummer Klaus Dinger were core members until 1971 when they departed to form the almostas-influential Neu! A willingness to play with form led to their greatest advancement — ditching traditional drums and guitar altogether to go fully electronic — while exploring pop-song conventions. In the mid-’70s, this was a radical concept, if not commercial suicide. Think about it: a band without a guitarist, and with a vocalist who sang through a vocoder in German or heavily accented English. Not very rock & roll. But that was precisely the point — Kraftwerk wasn’t interested in destroying existing systems like punk was. Rather, they imagined building completely new ones with undercurrents of nostalgia and playful humor. And because of this irreverent sensibility, they reached audiences far outside of those who only listened to “angry white dudes with loud guitars.” Or jazz fusion. “I came from a New Age-influenced background — so, Vangelis and Jean-Michel Jarre. In 1991, I got a copy of The Mix [album of remixed Kraftwerk hits]. And then all of a sudden you hear the influence,” says Jesse James Allen, an Orlando-based sound designer and electronic musician. “It’s extremely obvious where everybody got the idea to do things. And that’s when you fall in love with the history of the genre.” Unlike in Europe, electronic music wasn’t initially accepted in America. Yet remarkably, an edited version of “Autobahn” from the Kraftwerk album of the same name