12 minute read

NO ONE WILL EVER SILENCE ME AGAIN

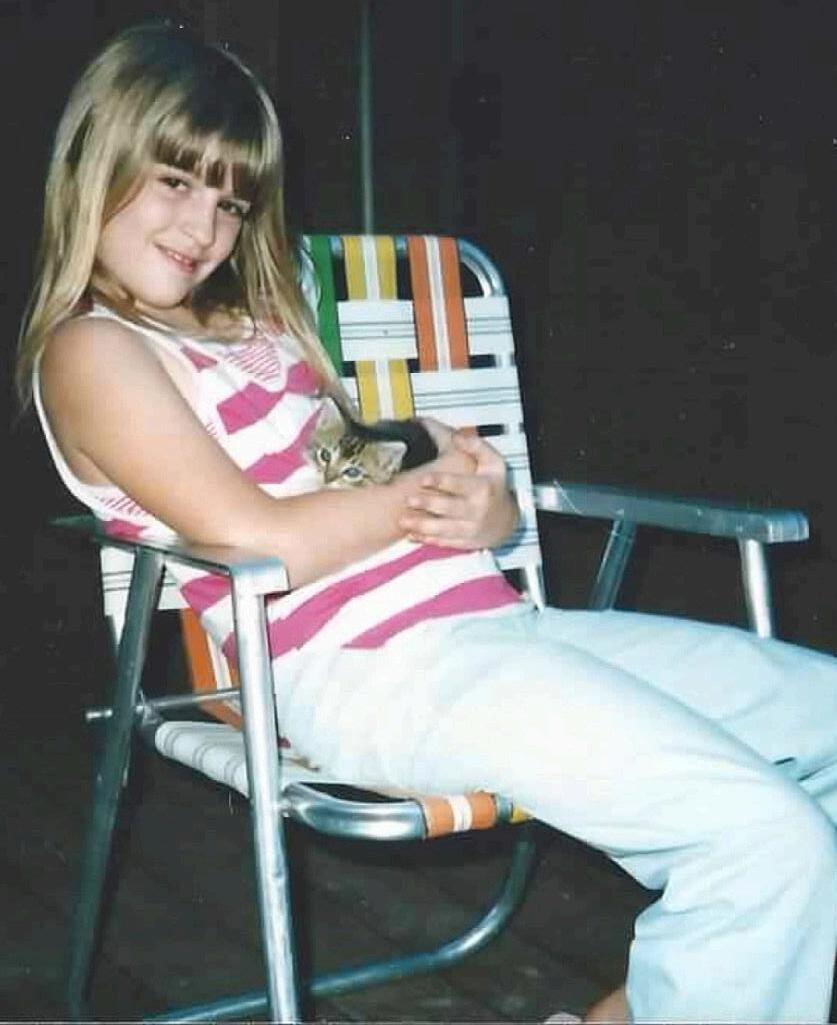

Donna Bulatowicz

“You are the prettiest little girl I’ve ever seen,” my new elementary teacher informed me, resting her strong, rough hand on mine as she knelt in front of my desk. I slipped my small, soft hand out from under hers and glanced quickly at her intense eyes, then away.

Advertisement

I focused on the getting-to-know-you sheet that Karen Smith, my teacher, handed out a few minutes’ prior. I started coloring a pink border around the paper. After introducing herself earlier, she mentioned that she was going to spend time getting to know each of us.

“What do I need to know about you, other than that you’re absolutely gorgeous?” Mrs. Smith asked, grinning, and tucking a strand of her short hair behind her ear. Snakes squirmed in my tummy. I didn’t know how to react, and I shrugged. My words had gone away.

Her warm hand was suddenly on my cheek, surprising me. “Aww, are you shy, my little girl?” She crooned as she rubbed my soft cheek with her rough thumb. I nodded and moved away from her hand. She told me not to worry, she would come back.

I swallowed hard, kept my head down, and focused on finishing the pink border. My mind spun and my intuition sounded an alarm. Something felt very off, but I couldn’t articulate what . My skin prickled like it had when the tiger at the Bronx Zoo watched me and mirrored my movements. My dad joked that it thought I was a tasty little morsel. I pictured my teacher as that prowling tiger and shook my head. I needed to focus on this first assignment, not let my imagination soar.

I worked on the getting-to-know-you paper, filling in my brother’s name, favorite colors, and things I liked to do: read and write, make arts and crafts, run wild on my grandparents’ farm, ride horses, play with My Little Ponies, She-Ra, Cabbage Patch dolls, and more. I focused on trying to write in my best handwriting so I could impress my new teacher.

“How are you doing, my little girl?” Mrs. Smith suddenly appeared by my chair, startling me. Her arm rested on the back of my chair, and I scooted forward. She moved her hand to the small strip of skin between my colorful shirt and my acidwashed jeans, tracing a pattern.

I shifted uncomfortably but was out of options to move unless I got off the chair entirely.

Mrs. Smith looked at my paper and asked me questions. I nodded, shook my head, or shrugged in response. I barely paid attention to her words. Instead, I focused on her warm, rough fingers etching a pattern into my skin, marking me as hers.

The recess bell felt like a physical and spiritual relief. I darted to the door for the first time ever. Since kindergarten, classmates routinely bullied me, often at recess. Mrs. Smith came outside with us, and every time I glanced in her direction, she was looking in mine. We girls gathered near the end of the asphalt, jumping rope, and talking about our new teacher. No one was quite sure what to make of her. One classmate pointed out that I was the only one Mrs. Smith showed any affection.

Mrs. Smith soon inured me to feeling of her hands on my body. She was very physical with me: picking me up under my arms and swinging me around, which thrilled me; tickling me and making me giggle until I cried; pulling me into her arms and/or onto her lap; entwining her fingers in mine; kissing me; and more.

I learned to ignore my intuition and delight in the attention and affection. She listened to me with her whole heart, used attachment techniques to create a bond, and offered to mentor me and teach me about teaching. I was used to teachers mostly ignoring me because I was obedient and quiet. However, Mrs. Smith actually saw me and treasured me. I thrived and quickly grew to love my new teacher. She proclaimed she loved me deeply.

During the third week of school, she told me she wanted to play a game to show me how much she loved me. She closed and locked the classroom door, checked that all the blinds were pulled, and stood me in front of her. She proceeded to annihilate my innocence, betray my trust, and steal the rest of my childhood.

I felt like I was underwater. It was difficult to breathe, to hear, to move, to see, to think. Time stretched like taffy. She smiled. She looked down at what she was doing and smiled. My heart shattered, my world disintegrated, and my beloved teacher smiled.

When she finished, she informed me that if I told, no one would believe me, and she’d ruin my life. I looked at her with haunted eyes. At that point, I didn’t have the words to describe even to myself what she had done. She had silenced me again, deliberately this time.

I was in shock and could not process what she did. I forced myself to go to sleep curled up on my chair. Mrs. Smith woke me a while later when the classroom was empty but for us. She startled me so much that I jumped into her arms. She cuddled me, rocked me, and soothed me, whispering words of love and reassurance. This began a pattern that continued throughout the year. She would sexually abuse me, then shower me with love and affection, creating the perfect conditions for a strong trauma bond.

In order to survive, I had to bury the memories quickly. Otherwise, how could I stay in that classroom, sitting at the same round table where she bound me with jump ropes and molested me during recess? How could I participate in lessons taught by the person who broke me? Sometimes my body seemed to function without me. My mind, my essence, departed. Dissociation meant survival. I floated through my days like a wounded ghost.

Over the school year, Mrs. Smith sexually abused me hundreds of times; she usually raped me multiple times every school day. She also abused me mentally and sometimes physically as well, especially if she was mad at me for trying to resist her molestations. There were times she called my mom and lied about my injuries. “Donna fell off the monkey bars and landed with a bar between her legs.” “Donna fell and landed on the corner of the bookcase.” Since I was not known for being graceful, these were reasonable scenarios.

I am not a perfect survivor. Mrs. Smith was usually tender and gentle when she “made love to” me (as she called it). She knew how to manipulate my body to get the response she wanted, which she insisted meant that I enjoyed it. Even though I wanted her to stop, it often felt good, which was incredibly confusing and painful for a little girl.

I enjoyed spending time with her when she wasn’t molesting me. I adored the times she did things just to make me smile; like arts and crafts with just me, decorating my hair with a crown of leaves, painting my nails, and more. I basked in the affection and attention she inundated me with; I had never been the center of anyone’s world, and it was intoxicating.

I liked it when she covered my face in kisses and told me how much she loved me. I felt warm and safe when I curled up on her lap with her arms tight around me and my head resting against her. I turned to her for comfort from the abuse. Only she knew why I needed the affection and reassurance, so only she could reassure me that despite how damaged I felt, I was still loved and lovable. I loved her. I sometimes enjoyed getting away with things, like taking her snack or soda, which would result in an indulgent smile from her. Other times, the lack of boundaries frightened me. I learned to block off the abuse and focus on the love, which I craved and clung to.

One question that always comes up is how she was able to do so much. The principal never walked around the school. She let everyone know she was mentoring me, and I was her teacher’s assistant. She kept me in from recess and lunch, when busy playground or lunch monitors wouldn’t notice one child absent. She kept me in from specials occasionally. She pulled me out of class sometimes to an empty storage closet or classroom. She had her desk angled so that no one could see behind it unless they were right there, and she had a strategically placed stack of books.

She groomed not only me, but everyone around me. Teachers and students became used to her showering me with affection; whenever she was near me, her hands were on me, and she often kissed me. She picked me up and held me with one hand between my legs, pulled me onto her lap, “adjusted” my clothes, went into the bathroom stall with me, and more, and no one batted an eye. She constantly called me hers: her baby, her baby girl, her child, her heart, etc.

I tried to disclose through behavior and words. I became a different child over the course of the school year. I regressed. I had nightmares, anxiety, a heightened startle response, depression, panic attacks, and more. I withdrew from others. My personality changed. I thought I was clear with adults when I told them that Mrs. Smith was too handsy with me and I didn’t like it; that I didn’t want to be around her; that she scared me, etc. No one asked me why, and I felt even more alone.

It all stopped at the end of the school year. Even though Mrs. Smith lived nearby, she didn’t risk showing up at my house unannounced. She asked me to stop by hers, but for obvious reasons, I did not. As the months passed, her power over me faded.

The next school year, it struck me that she could be molesting another little girl. I mustered up my courage, excavated deeply entombed secrets, and I told on her. I was petrified, but I didn’t want Mrs. Smith to harm another little girl. I trusted in the justice system to do the right thing. I soon learned that the injustice system focuses more on protecting predators than helping victims.

The police assured me that a woman would never molest a girl. They asked me why I didn’t remember every detail of every incident and in full chronological order. They questioned why I described an incident as if I viewed it from above. They seemed blissfully unaware of trauma’s impacts on the brain during and after traumatic events. Given their disinterest and doubts, I stopped talking. They heard about a handful of incidents. They did not ask me the questions that they would have if a man had molested me. They chose to do only a superficial investigation. They blamed me when she threatened to harm herself. She got away with sexually abusing me, and then she and her enablers retaliated against me—stalking, harassing, and bullying me—for almost all of my teen years, until I moved over 1,000 miles away. Luckily, family believed and supported me. My parents put me in therapy when I told on Mrs. Smith. Therapy for sexual abuse survivors was in its infancy. The therapist helped me deal with my feelings and some memories, but when I asked for dolls to help explain something I couldn’t find words for, she refused. I stopped sharing my memories, and I stuffed everything down deep inside me so that I could survive. I felt silenced again.

I also had multiple synchronicities happen, including some friends who knew Mrs. Smith talking with me about her. One friend said, “Oh, if Mrs. Smith were here, she’d just love you! You’d be her favorite, and she’d love you so much! You two would be so close.” With all of this happening,

I used to be terrified to speak in front of peers. Since I’ve reclaimed my voice and am telling some of my CSA story, that fear has vanished. I’ve shared pieces of my story with friends, family, and strangers. I created and gave a training to preservice teachers. I am modifying it for in-service teachers and other professionals. I want to schedule a visit (and hopefully a training or speaking engagement) with the same police department that so callously dismissed me. I will also request to train teachers at the same school district where my experiences occurred.

About The Author

I’m learning more about the long-term impacts of sexual abuse, complex posttraumatic stress disorder, developmental trauma, and ways to heal. I’m journaling every morning and often at other times. I participate in talk and EMDR therapy, and I attend meetings with an online support group. I joined survivors’ groups on Facebook. I am starting to incorporate meditation, mindfulness, and yoga more regularly into my day. I’m learning ways to deal with the flashbacks and accompanying emotions.

No one will ever silence me again.

Dr. Donna Bulatowicz lives in the beautiful state of Montana where she teaches in the educator preparation program at a local university. Her main area of expertise is inclusive children’s literature. She recently completed her term as chair of the Charlotte Huck Book Award for Outstanding Fiction for Children.

You can reach Donna on her Facebook page, or email Donna.