PLAYGROUND / GROUNDPLAY: THE FRANKLIN PARK PLAYSTEAD

17

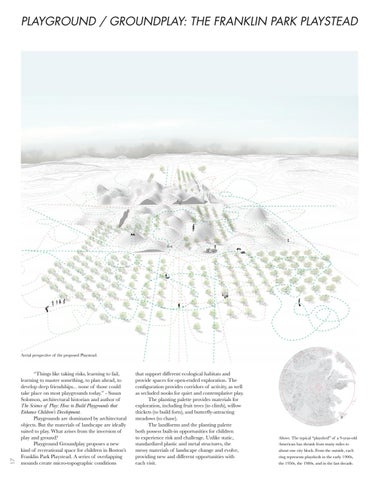

Aerial perspective of the proposed Playstead.

“Things like taking risks, learning to fail, learning to master something, to plan ahead, to develop deep friendships... none of those could take place on most playgrounds today.” - Susan Solomon, architectural historian and author of The Science of Play: How to Build Playgrounds that Enhance Children’s Development. Playgrounds are dominated by architectural objects. But the materials of landscape are ideally suited to play. What arises from the inversion of play and ground? Playground Groundplay proposes a new kind of recreational space for children in Boston’s Franklin Park Playstead. A series of overlapping mounds create micro-topographic conditions

that support different ecological habitats and provide spaces for open-ended exploration. The configuration provides corridors of activity, as well as secluded nooks for quiet and contemplative play. The planting palette provides materials for exploration, including fruit trees (to climb), willow thickets (to build forts), and butterfly-attracting meadows (to chase). The landforms and the planting palette both possess built-in opportunities for children to experience risk and challenge. Unlike static, standardized plastic and metal structures, the messy materials of landscape change and evolve, providing new and different opportunities with each visit.

Above. The typical “playshed” of a 9-year-old American has shrunk from many miles to about one city block. From the outside, each ring represents playsheds in the early 1900s, the 1950s, the 1980s, and in the last decade.