Vol. 53

The Emerson Review is an annual literary journal by undergraduate students at Emerson College in Boston, Massachusetts.

All genres of original, unpublished writing and visual art are considered for publication.

The reading period for the 2024 issue ran from August 1st through February 1st. All submissions are handled anonymously. Materials can be submitted to The Emerson Review through our online submission manager, http://emersonreview.submittable.com. Complete guidelines can be found on our website.

General questions and comments should be sent to submissions.er@gmail.com. https://websites.emerson.edu/emerson-review

Cover Design by Katherine Fitzhugh

Design by Isabella Chiu, Eden Ornstein, Aubrey McConnell, and Maggie Duggan.

Printed by Flagship Press.

©2024 The Emerson Review

MASTHEAD

Editor in Chief

Gracie Warda (Fall 2023)

Nina Powers (Spring 2024)

Managing Editor

Anna Carson

Assistant Managing Editor

Nina Powers (Fall 2023)

Lily Labella (Spring 2024)

Fiction Editors

Gyasi Asim

Daisy Macdonald

Poetry Editors

Annalisa Hansford

Clara Allison

Lily Labella (Fall 2023)

Leïssa Romulus (Spring 2024)

Nonfiction Editors

Izzy Astuto

Bronwyn Terry

Head Copyeditor

Ella Maoz

Copyeditors

Olivia Trzaski

Nina Serafini

Rebecca Kim

Laurie Hilburn

Melina Gardiner

Web Editor

Kinsey Ogden

Social Media Manager

Andy Ambrose

Head Designer

Isabella Chiu

Designers

Eden Ornstein

Aubrey McConnell

Maggie Duggan

Consultant

Arushi Jacob

Faculty Advisor

Amber Lee

Staff Readers

Leïssa Romulus (Fall 2023)

Emily Jacobsen

Everly Orfanedes

Ocean Muir

Cari Hurley

Ella Maoz

Khira Moore

Kira Salter-Gurau

Alyssa Laze

Tessa Donohue

Madison McMahon

Elyse Gobbi

Rebecca Neary

Roni Moser

Sally Beckett

Kyndle Fuller

Emma Winiarski

Liz Fleischer

Casey Richards-Bradt

Color of Memory

Sophia Zhao

Mourning Song

Rachel Walker

City on Fire

Juanjuan Henderson

How to Know the Dollar in Delhi

Mandira Pattnaik

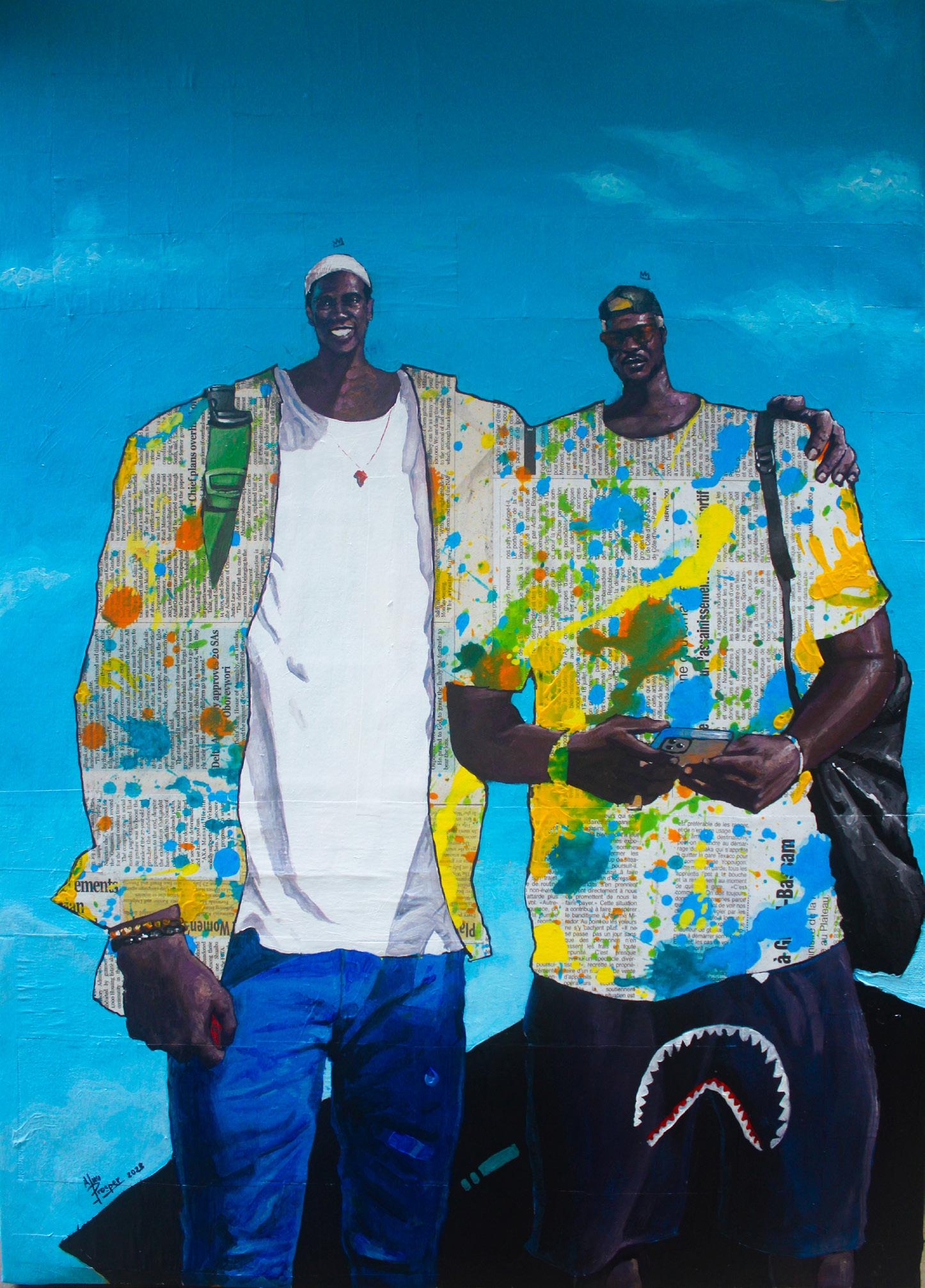

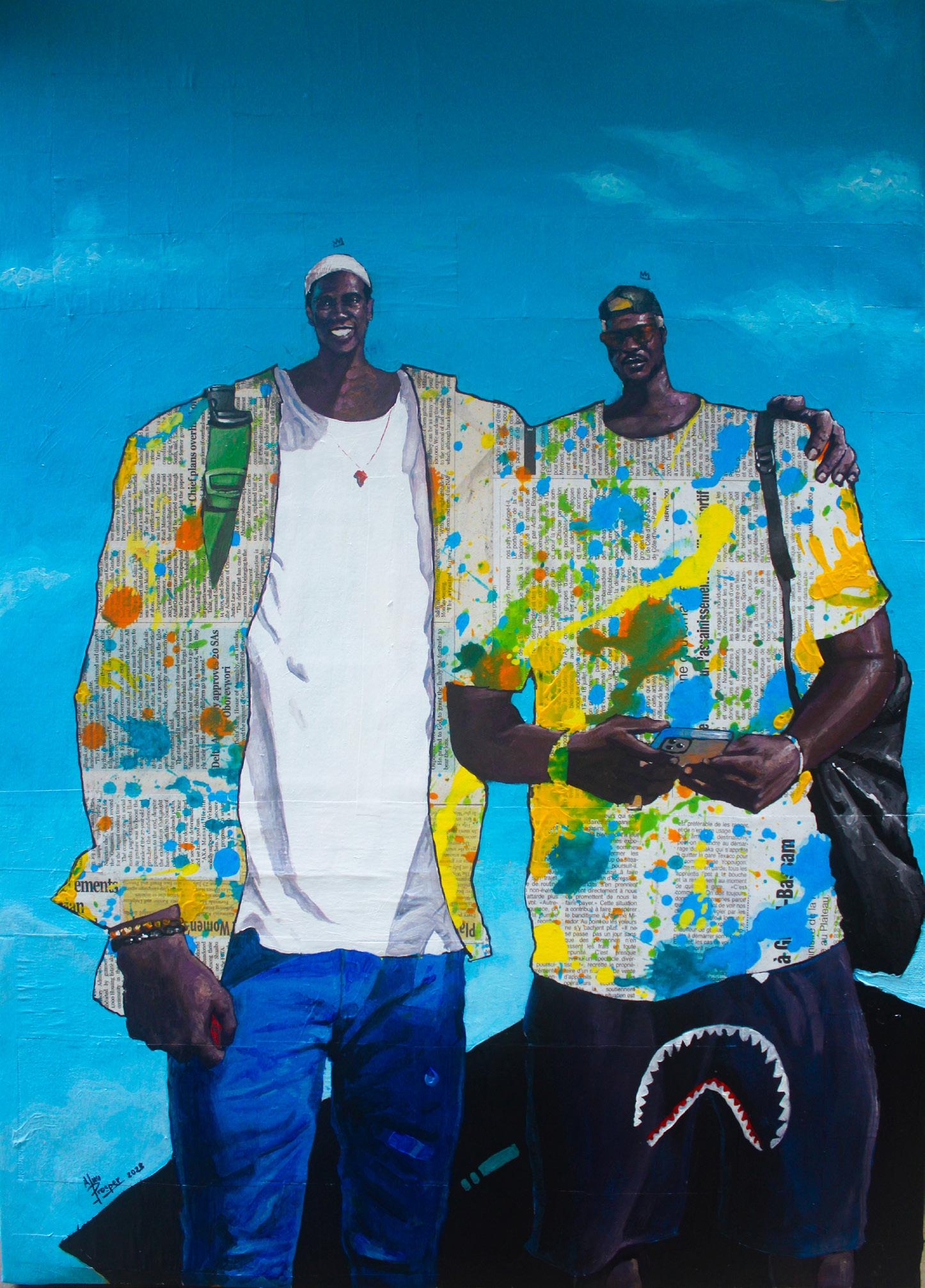

Abfillage

Aluu Prosper

I Saw Antoni Porowski Jogging

Michael Savio

Dusk Over Kralery

Karly Hou

Us Cajun South Brown Folk

Shome Dasgupta

Caught on Barbed Wire

Juanjuan Henderson

The Hologram

Erica Rivera 18 Destiny Fagbohun

Sitting on a Granite Boulder

Beside a Pond in Maine

Jane McKinley

Maegan Collins

Opia

1 2 3 4 7 8 11 12 15 16 19 20 21

She is my mother no she is my baby

Meghan Proulx

Focus on Fabric

Maegan Collins

Being Dad

Michael Mark

Howl

Karly Hou

The Skull of an Unnamed African Boy

Stephenjohn Holgate

A Tree that a Monkey Cannot Climb (Maymun Çıkmaz Ağacı)

Julia Prikhodko

An Analgesic for the Antichrist

Brett Hymel Jr.

Caveat Emptor

Jay Daugherty

Why

Brigs

the

Water Tastes Like Cigarettes

Town

Larson Glacier Peaks Kathleen Frank Oh Aliyah Cotton Featured Authors 22 23 24 27 28 35 36 41 42 51 52 53

COLOR OF MEMORY

Sophia Zhao

1

MOURNING SONG POETRY

Rachel Walker

A man came to buy the month-old calf while I was sleeping. In the morning, the mother cow’s silhouette wades

through the storm. She stands at the edge of the barn, her eyes low and bulging like overripe berries. She calls to me again and again and again against the scream of wind pushing the tall pines, granite shifting deep in stony hills.

The storm clears, and you and I spend the afternoon lying beneath an oak tree perched above the farm.

All day, you’ve been whistling, bella ciao, bella ciao, bella ciao ciao ciao. The breeze reorders the mosaic of leaves above us. We talk about the meaning of names—how, in the Bible, I’m your second wife. A leaf-sized shadow moves across your face. When you leave, I find your book on the windowsill:

Bella Ciao. I sing it to myself in bed against the cow’s cries.

2

City on Fire

3

Juanjuan Henderson

How to Know the Dollar in Delhi

NONFICTION

Mandira Pattnaik

1Tap into your earliest memories of Dadu. Reclined in his armchair, his favorite spot, like the place owned him, a bunker where he hid, and not because he was mounting an attack, but from where he could keep an eye on the entire house and its occupants and see farther toward the fruiting trees—their mangoes, guavas, berries—and beyond still, watching over the pond where thieves were known to smuggle in bait and carry back a rohu or two. Remember him talking about rupee and prices like they were two sides of a weighing scale he needed to balance as the patriarch of the household. Remember him wondering aloud about life post-retirement and ranting about things being unaffordable. Rupee versus groceries; rupee versus fresh vegetables. Never dollar, though, when you lived in a town many miles east of Delhi.

2. Drop some years and arrive at a wedding in Kolkata, where your cousin, who is older than your father (because Dadu had eleven children and your cousin is the son of the eldest aunt), is hosting a wedding reception for his eldest daughter. You have never met this cousin, who is Indian American and immigrated in the ‘70s, or his daughter before. At the center of a premium hotel’s ballroom, the bride (again, much older than you, born and raised in Seattle or Washington, D.C.—or someplace else you’re not sure of because every other relative around you is naming a different city and nobody is certain, so everyone decides it’s America) is meeting her family here. Her younger sister, also older than you, struts about in a golden outfit, a cross between a saree and a gown, and both women talk in such accented English that most of the people gathered can only nod as though they understand. The charade goes on for some minutes before the cousin and his daughters are called away to converge on the raised platform in the corner of the ballroom for the Hindu wedding rituals. The bride’s grandmother, your paternal aunt, walks up to you, and after a brief conversation, produces a couple of dollar bills from her purse to show you, saying, “From when I visited Dallas.” You notice the color and how well she has preserved them.

3. Pray for something to happen, anything. So the many parents with children abroad, part of Dadu’s large family, stop worrying. You are left wondering: Supposedly, there’s a magic trick playing behind the scene: boys will use engineering degrees that’ll lead to employment offers abroad, which will lead to a flurry of activity around their homes, and phone calls going back and forth among the various branches of the family. And then nothing. Nothing happens as people vanish into a world you know little about. Airmail every few months in the first couple of years, then they’ll promise to call, as smart people do. The calls will dry up too. Every once in a while, though, you will listen to the elders discussing how much the children abroad earn in dollars

4

4. Be quick to learn the difference. Between rupee and dollar, between here and abroad, between us and them. Learn about brands and products, about homes and lifestyles, about caramels and popcorns and waffles. Learn about the craving for idlis and dosas as they are talked about in appropriate nostalgic tones, and puchkas and puris being mentioned in conversations. Stop by when your Dadu and the rest of your family gather around the phone receiver when that coveted international call comes. Be curiously disenchanted when the mothers—your aunts—frail and needing help themselves, say that they’ll make payasam varieties for the cousins and their wives when they visit.

5. Now you’re graduating from high school in a big, bustling city. Be in the know when your classmates and neighborhood friends weave dreams about leaving for the States, marvel at their seamless threading, flawless warps and wefts, as they plan accurately, and after a few years, fly away to earn in dollars. Sixty-five rupees to a dollar. See the difference? they say, sort of mocking you, because you’ve landed a job here—in a government department too, having beaten half a million competitors for the same post—but you’ll never earn in dollars. It’ll be rupees all the way.

6. Be baffled. Everything changes so much after India’s economic liberalization. Be introduced to the word “globalization.” Remember it in the context that most of your friends have now gone abroad, and they’re never coming back. Thank god for Facebook. Quit it soon though, because the place seems like a showcase where said friends exist to race against each other in posting pictures of Golden Bridge, or Sydney Harbor, or tube stations, or Hollywood Walk of Fame, or Niagara. Thank god for the swanky malls that sell American-branded clothing. Visit them often.

7. Lend an ear when some of your friends here want to vent. They rue being left behind and are simply looking to marry. Bonus points for suitors who will take them to dollar country.

8. Be happy you didn’t fall into that bracket of girls waiting endlessly to be “taken,” like Barbie dolls on a glitzy mall shelf. You’re presented with a situation that builds itself up over several months, and you’re sure, at the end of it, that the friend and colleague is sufficiently attentive to your needs and feelings.

9. Marry him without delay. On the wedding day, ignore your mother’s mentions of this-or-that cousin and this-or-that friend of yours who called the home landline phone from the States. You know the call was to express regret for not attending your wedding because of meetings and office tours. Applaud their honesty when one of them remarked something about skyrocketing airfares being unaffordable against their earnings in dollars.

10. Maybe try to forget the rupee-dollar difference until your only sister is engaged to be married to a boy who is from Hyderabad but lives in Ohio. Keep forgetting, then keep being reminded of how this groom fancies his name-brandonly wardrobe, how he travels economy but has a flair for hunting down the lowest rates—what he buys with his dollars. You don’t need to hear those details, but the words keep echoing in the house until the wedding day and beyond, until it assumes the odor of stale air, the kind that hangs around when produce is no longer fresh at a farmers market. You get the drift. Or so you falsely presume.

11. Feel helpless when those eighty- and ninety-year-old aunts and uncles who have children abroad wish to “see” them and their grandchildren one last time, and those aunts and uncles request you to do something, but even Skype doesn’t connect. Sit beside their sickbeds, where the caregiver has arranged a tray to hold all the

5

medicines and wipes, and admire the lone chrysanthemum someone has placed in a glass. Overhear the others discuss Arya Old Age Care Home and Hiranandani Hospital. Remember there are no hospices here, which is the reason the children’s dollars are of no use, even if wired back home. Talk about the jamun tree at your ancestral home or the mangoes you picked that Grandmother pickled. Even several hours later, feel something is amiss as you replay your last conversations with your aunts and uncles.

12. Become like Dadu. On rainy evenings, find yourself gazing at the gulmohar outside your apartment in Delhi. Sit in a chair by the window while the TV plays an odd monotonous drone—a debate or something, it’s all the same—before returning to double-checking grocery receipts and electric bills and phone bills and credit card statements, though your age is less than half of Dadu’s from the last time you saw him. Think about him. Think of the telescope he longed to buy but never could. Think of the pungent smell of mustard oil that he detested. Just for fun, sometimes convert your receipts and expenses into dollars and be surprised. Eighty rupees to a dollar—the current exchange rate—must make the dollar feel so strong.

13. Decide on something that is unlikely to change when your sister visits you from Ohio some years thereafter with two kids and a husband who works in software. You haven’t seen him since their wedding. Look after her as a lighthouse would look out for ships. Cook the meals she misses when she’s in America, with ingredients ordered on Amazon. When the delivery person comes, braving the incessant rains to deliver honey, mangosteen, and bamboo shoots, notice his harried expression and torn slippers and wonder how much he is paid. Remember the dollars his company earns. A few days later, you overhear your sister saying something to her diasporic friends in America about the Indian-style toilet in your Delhi home, how she’d prefer to stay in a hotel and not in your tiny, damp apartment the next time she visits because she can afford it. Well, of course she can—with her dollars. Learn how the feeling registers differently because you’re many years older and have always treated her more like your baby than a sibling. Guess (and hope you’re estimating correctly) just how much an older sister is valued in dollars against rupees.

6

7

Abfillage Aluu Prosper

I Saw Antoni Porowski Jogging

NONFICTION Michael Savio

Isaw Antoni Porowski jogging, which was exciting. I was crossing Houston Street, heading to the Trader Joe’s on 6th and Spring, when I spotted a handsome, muscular (but not intimidatingly so) man, shirtless and glossy with sweat, running in my direction. My journey had just taken on renewed import. Only when he got closer did I realize . . . hey, I knew that sharp nose and Michelangelo-chiseled chin, which on a lesser specimen would betray the distinctly Canadian geniality that oozed from his maple-syrup brown eyes. It was Anthony—no, Antoni (I’d look up his last name later): the chef-turned-life-coach from Queer Eye, that one Netflix show I long ago would deny having ever watched, jogging right by me. And shirtless—did I mention he was shirtless? God, what a treat.

I saw Antoni Porowski jogging, and I felt alive. That moment of recognition; the flurry of I know you. The interruption was welcome, giddying. A fuse is lit within your heart upon spotting a celebrity in public, not unlike the feeling you may get when first laying eyes on the Golden Gate Bridge, or the Mona Lisa smirking in her glass casing at the Louvre. No matter your personal taste, you are struck by the grandeur of this work—this entity that you’ve seen replicated countless times, but never the original, and never with your own eyes. That’s the real impact of fame: you feel connected to the world. You become witness to an icon—the magnitude of the word itself, for the first time, proves tangible to you. You become one of the “mass few” who have found new insight into why these apotheoses appeal to so many, how art becomes Art, and where lies the secret motor that drives human intrigue and exceptionalism. I could see others on the street stop and turn their heads as Antoni jogged past them, no doubt experiencing the same epiphany, the same rush of radical connectedness I’d felt. I smiled at a stranger to my left whose jaw had dropped. She and I had just seen Antoni Porowski jogging.

I saw Antoni Porowski jogging, and it made me proud. It was such a New York thing—to stumble upon a celebrity going about his day while you’re going about yours. After all, aren’t we all—celebrities and non-celebrities alike—just going about our days in this city? I’d seen others before: Steve Buschemi at a breakfast spot downtown, Kim Petras in a stairway in Chelsea, some cast member from Saturday Night Live at some bar. But Antoni was going about his day in my neighborhood. Didn’t that mean he was likely going about his day in our neighborhood? The possibility was thrilling.

I saw Antoni Porowski jogging, which reminded me that I, too, jog. Well, have jogged. Frankly, it’s been a while, but I’m nevertheless familiar with the sensation. I have also felt the pavement slap against my soles and my chest heave with a strain that I’ve been led to believe will prolong my life, but at the moment, seems to portend its vicious end. Does his chest heave in the same way? It must, it must. Maybe I should go for a jog later this afternoon. What a magnificent realization, to know that Antoni Porowski and I are both joggers.

I saw Antoni Porowski jogging, and I didn’t take a picture. I am not one of those people: the ones who must document every facet of their day to prove to their former classmates still stuck in their sleepy Midwestern hometowns that their big

8

city lives are so much more pristine and cultured than theirs ever will be; the ones whose pretensions and insecurities are so fixed in their faux selfie smiles that not even Instagram’s “Paris” filter can scrub them away; the ones whose compulsions to “share” their realities only obfuscate them further. Can we not let moments exist in the present anymore? I worry about my solipsistic generation sometimes.

I saw Antoni Porowski jogging, so I texted my sister to tell her. She loves Queer Eye and would especially love to know that I saw Antoni Porowski jogging. Not long after I came out to her, my sister visited me in college for a week; we’d danced around the topic of my coming out to our parents by spending hours watching the show’s first season. We’d quibbled over whose wardrobe retrofitting was the best and whose haircut was the worst. We’d laughed about how little screen time Fab Five member Bobby Berk would get and rolled our eyes over the hackneyed “cultural expertise” that Karamo Brown would bestow upon the week’s subject. Yet, by the end of each episode, we’d both be crying. We’d been swept up in the schmaltz, sure, but we’d been swept up together. I miss those days. Four hours after I told her I’d just seen Antoni Porowski jogging, my sister texted back, “Cool!”

I saw Antoni Porowski jogging, and I’m pretty sure he saw me. I felt his tender eyes flick over to mine, jerking me into acknowledging that I had a body, that I took up space, that I was more than what I could see—all because Antoni Porowski, the guy from Queer Eye, had locked eyes with me! Would he have done so if I had not been staring at him? Celebrities must always be on the lookout for being looked at. What is it like to never disappear? When does the constant exhilaration of being ogled grow rote and enervating, like a heroin addict whose overused, swollen veins have dulled his chances of ever getting high—truly, wonderfully high—again? I pitied Antoni Porowski for a second. But then again, to him I was just another rubbernecker, another body, another pair of eyes glued to his body while he was out for a jog. I was no one and everyone. I was not me. And if I was not me to Antoni Porowski, what made me me to anyone else?

I saw Antoni Porowski jogging, and I realized that I am ugly. Antoni Porowski is beautiful. He was always beautiful on TV. He made women and men lust after him, and then write Buzzfeed listicles about how they lusted after him, which would include photographic evidence of why he was worthy of lust. But believe me: in real life, Antoni is so much more beautiful than you can imagine (I almost wish I had a photo to convince you of this). It is hard to delude yourself into believing you might be worth looking at after you’ve seen someone who demands to be looked at. You might think of yourself as decent-looking, perhaps even above average. You reassure yourself that those on TV, or in magazines, or with thousands of followers on Instagram are the select few—the gaudy and the gaunt, the unblemished unreal. They are far away; they are caked in makeup; they are photoshopped, surely. But once you see Antoni Porowski jogging, you understand that they are all real, they are all beautiful, and you are not.

I saw Antoni Porowski jogging, which reminded me that I am incapable of love. To love another person is to surrender yourself completely to them (or so I’ve heard), to bare your soul and all its intricacies and contradictions, its foibles and enmities—a proposition most frightening and futile. Loving is a selfless act, and I am not selfless. Antoni Porowski is selfless. On Queer Eye he teaches each episode’s subject how to cook for themself on a budget, to take charge of their physical and emotional health, to identify and celebrate that within themself which makes them special and allows

9

them to flourish. I do not teach anyone how to flourish. I sit at home and masturbate and scroll TikTok and eat fistfuls of high-fructose corn syrup and write words and delete words and fantasize about a life in which I do not do these things but, instead, I teach people how to flourish. I do not tell people this because I am afraid that if I do, then no one will love me, but apparently, if I don’t tell people this, then no one will love me. What gives? I want to be loved by one person in the way that Antoni Porowski is loved by everybody, but it seems unlikely.

I saw Antoni Porowski jogging and it convinced me once and for all that there is no God. A non-denominational Christian friend once described to me her experience of meeting God. She was a teenager at a sleepaway camp at which she had no friends, and one wintry night she trekked deep into the woods that surrounded her cabin. She soon found herself crumpled on a pile of dead leaves, sobbing and wishing she was anywhere else, wishing she got along with the other kids, wishing she was not so utterly alone. At that exact moment, she felt an embrace—a mystifying, needed embrace—as if some force of pure warmth had hugged her from behind to calm and reassure her that, in this life, there is no such thing as being alone, and no such thing as being unloved. I didn’t buy it. I privately scoffed at the story and presumed the warmth she felt was the early stages of hypothermia. But really I was— and still am—envious. Envious because I have never felt that glowing, comforting embrace during my worst moments of despair. I have never felt, from a divine spirit, that I am loved and not alone. That is, until I saw Antoni Porowski jogging. For a brief moment, that radical isolation that colors the whole of human experience was suspended. When I saw Antoni Porowski jogging, and when I saw other people see Antoni Porowski jogging, I felt as if I had glimpsed the mighty, invisible arms that connect us all on this earth and shepherd us along our unique, borderline Sisyphean, paths in life. I worry this was a gross misinterpretation. I fear that we are all absolutely, unbearably alone.

I saw Antoni Porowski jogging, and then he kept jogging. He continued going down Houston toward the West Side Highway. He sidestepped a crevice in the crosswalk on Greenwich Street that I’ve noted, and cut over onto the Hudson River Greenway, where he continued jogging north. Some people stopped, turned, and gawked as he passed them, but he just kept jogging. The National’s latest record was playing in his AirPods (he’s a huge fan). After around three and a half miles, he stopped to stretch before turning around and heading back down the path, crossing the highway again and running down Houston, and finally approaching his building where he shook off the sweat, entered, and closed the door behind him. He greeted Neon (his rescue dog), who lapped at his hand as he walked in. He took a shower, he got dressed, he answered a few emails, he ate an apple from his fruit bowl, he took a phone call from his agent, he met up with his fiancé for dinner at a new Italian place in Tribeca, he took a trip to Los Angeles for a meeting and then one to Maine for a weekend getaway, he did a press shoot for his new National Geographic show, he posted an Instagram photo that went viral, he had sex and he watched a couple of movies and he told a story to friends at a party that got a good laugh, he found a lot of reasons to smile and feel excited and satisfied and loved, but also a few reasons to cry and feel upset and alienated and hopeless, and he never for a second thought about how he saw me while out jogging.

10

Dusk Over Kralery

Karly Hou

11

Us Cajun South Brown Folk

POETRY

Shome Dasgupta

Two steppin’ Brown folk, Creole Lunch House Brown folk, Bindi laughin’ Brown folk —gathering ‘round the sun holding hands in circles, we stick our tongues out toward the mud and clay.

Muthafuckin’ Brown folk, Brown-skinned Brown folk, Black-skinned Brown folk

—zydeco rattlin’, moon filled music, red eyes and clanking bangle bracelets with nose-pierced, gold-silver shine, we celebrate our ankles.

Dem’s my cousins Brown folk, Acadiana Girard Park Brown folk, Gumbo sippin’, masala Brown folk —tin cupped palms like branches around the wings of an owl, our dance of the peacock, we look into the Mississippi and see the reflection of the Ganges.

Okra- and daal-bathed Brown folk, Aloo and fish fry Brown folk, UL Lafayette Brown folk —we look at each other like we know each other, never saying a word, maybe just a nod, maybe a glance, we speak in motherland talk, a way to shake hands—a namaste.

12

Atchafalaya Basin Brown folk, Lake Martin sunset Brown folk, Bhagavad Gita temple Brown folk —Diwali children cracking pecans in green fields while sari aunties hunt snakes with shovels, frogs hiccup stories about the pond’s history, under parking lot lights, we play cricket with untucked shirts. Sangeet singin’ Brown folk, Do-si-do dosa Brown folk, Tabla tappin’ Brown folk, Puja and Sanskrit Brown folk, Festival International de Louisiane Brown folk, Crawfish peelin’, canoe paddlin’ Brown folk —us Cajun South Brown folk.

13

14

CAUGHT ON BARBED WIRE

Juanjuan Henderson

15

THE HOLOGRAM

FICTION

TErica Rivera

he hologram appeared in the park overnight, without notice or fanfare. Some thought it was a guerrilla art project, others an ad. The city, of course, eventually announced (after many confused, angry calls to elected officials) that it was just a piece of public art, and that, like the many other governmentfunded works in the city’s parks, building lobbies, and public plazas, the hologram had been commissioned by the city’s arts and culture minister, who ordained that a digital artist born and raised in the city—or rather, in its poorest and most structurally under-resourced suburb—would design this particular installation.

Okay.

Satisfied many.

Maybe most.

The hologram was in a small park across the street from your apartment complex—not too large, ten stories, and modern, with a new elevator and a gym, and carbon monoxide detectors in every unit. On the ground floor, running on the treadmill in the gym, you could see in the center of the park a shimmery blue-green haze shaped into peculiar, unstable forms, ever morphing slightly, distorting your perception of what appeared by and behind its edges, like the flames of a large dancing fire.

You could see people stopping to look at it, their faces far away enough to teeter between expressions of either wonder or disgust, you could never tell. You could only assume that the faces of disgust belonged to those who walked away quickly; you could only assume the faces of wonder belonged to those who stayed.

Many stayed.

Maybe most.

It started to be that you’d work out longer, more often, to figure that out. The longer you kept your legs moving forward beneath you, the more data you had to work with. Of course you saw so many people stopping to marvel when you worked out during lunchtime; it was all parents, their kids mouths agape, as amazed by the hologram as they soon would be by trash on the ground. The parents didn’t know what the hologram meant, or didn’t care, snapping selfies with it behind them as though it were a shrine (multiple times, always; you had to imagine the glare of the sun made it hard to get a good shot), then writing hashtag-packed captions through transition sunglasses while their little ones divvied up the trash and ate it.

Of course they would stick around.

So you couldn’t go off that alone.

Nighttime was worse. At night, the hologram drew whole crowds—not just families, but groups of teenagers, young adults, elderly people. You had to wonder where all these people came from sometimes, changing the resistance on the treadmill to the lowest setting so you wouldn’t tire your legs out too quickly. You didn’t want to have to switch to chest presses on the weight machines, located just behind a thick

16

pillar in the center of the gym that would’ve blocked your view of the park and the masses constantly swarming it.

Swarming the hologram.

Swarming your street.

A few times, you thought about calling the police. Any number of reasons would have sufficed. The hologram was bright and on 24/7, which posed many problems. Two car accidents had occurred on the strip of street between the park and your apartment complex since the hologram’s installation. Both times the driver, distracted by the hologram, had hit the car in front of them at over twenty miles an hour, resulting in a few broken bones and plenty of vehicular damage. More was sure to follow. The brightness, apart from being distracting to drivers, also made it difficult for the many homeless people living in the park to sleep comfortably, which housing rights activists had called “deplorable.” Thus, they (the homeless, not their activists) had begun sleeping on the sidewalk in front of your apartment complex, which was distracting to you since only a thick pane separated you from them when you worked out and watched the park after dark. And the excess light the hologram was directly responsible for was nothing compared to the noise and air pollution it was indirectly responsible for: more people were driving, parking, and walking on your street than you even thought possible. The weather app on your phone normally reported an Air Quality Index (AQI) of about forty-nine, which was three points below the average in your county; now, it regularly reported an AQI of over fifty-five, three points above the county average, and two points above the threshold at which it begins to induce minor health problems in highly vulnerable populations. This was true even after dark, the park attracting larger and larger groups with each passing day, those who continued to loiter past 8 p.m. technically breaking the law since a city statute etched into big metal signs at the entrances to the park barred one’s mere presence there past sunset. And not to mention all the hooting, hollering, drinking—and, you were pretty sure, intravenous drug use—that was now normal and popular at the park, around and on top of the hologram, which visitors seemed incapable of not climbing all over and sticking their heads and appendages in, trying to see (be?) “inside” it.

You were far enough away that you couldn’t be sure it was intravenous drug use, but you knew if you called the police and asked them to investigate, they’d see what you were seeing. What you were sure you were seeing. What you were sure you were seeing every night, drenched in your own odorous sweat, sometimes until sunrise, as shocked at how you had managed to keep running all night as you were at how they had managed to keep going all night: partying, dancing, touching, splayed out over the park benches, feeling each other against the walls of the handball court, tangling their flushed limbs in the knotted crosshatches of the tennis nets, and especially loudly and spectacularly, finding each other on the ground next to the hologram, moving body onto body onto body onto body, drenched in their own odorous sweat, awash in a sea of cool blue pixels slipping off their perfect, holy flesh and onto the grassy knoll around them like drops of digital dew.

You had every right to call the police. You knew they would lock every single one of these people up.

But you also knew that would change nothing. The hologram would persist, and so too its draw. There are always more homeless people, there are always more selfie parents with trashy kids, there are always more teenagers and young adults and elderly people, there are always more hooters and hollerers and nocturnal alcoholics

17

and intravenous drug users and people just looking for a place to lie down and feel.

Calling the police would accomplish nothing.

This was a structural issue, demanding a structural solution.

You’d started recording your night sessions early on, after talking to your neighbors about what you’d seen and having them disbelieve you, dismiss you, discredit what you’d seen with your very eyes. How would they know? How could they know? You were the only person ever in the gym that late; you were probably the only tenant who was ever even awake that late. The windows of their apartments didn’t even face the park; the only place in the building where you could get a decent vantage point from which to see everything—the sprawl of the park and the hologram at its center—was exactly where you were, in the gym, on the treadmill.

Of course you would know.

Of course only you would know.

The treadmill had a little ledge at the top of its interface panel, ostensibly so you could prop up your phone and use it while you worked out, but it also allowed you to film what you were seeing as easily and professionally as if you’d had a tripod, an expensive film camera, or experience in digital video production. You didn’t have any of those things. It didn’t matter. It didn’t take long to amass all the evidence you’d ever need. You knew it would have convinced the naysayers if they’d answered your texts or their doors when you knocked. If they’d actually listened to you at City Hall; if the newspeople had taken you even a little seriously. If any of those so-called human rights organizations had spared five minutes to call you back. You even emailed them all a link to a folder containing all the footage you’d collected, which you’d painstakingly uploaded to the cloud, after compressing the files so it wouldn’t take as long for them to download, or take up too much space on their hard drives. You didn’t want to inconvenience them. You just wanted to prove them wrong. You just wanted them to see what you were seeing. What you had to be seeing. The footage didn’t directly implicate anyone, no; and no, it didn’t necessarily clearly depict any of the things you were sure you were seeing; but you knew it would become proof positive when placed alongside other evidence—like your eyewitness testimony, or the eyewitness testimonies of the police officers you were sure someone would call, even if you personally didn’t consider calling the police an option (because it wasn’t a structural solution, and this was a structural problem), like the body cam footage! The body cam footage. Yes. Someone would call the police eventually, and they’d go out there and they’d see what you were seeing, and their body cams would record everything, and even if that wasn’t enough to convince people (you knew how people felt about body cams these days, so eager to disbelieve in a technology that couldn’t do anything except show you exactly what you pointed it at), at least they’d have your footage. They could pair their footage with your footage, and prove it was real. Prove it was all real. Prove you were really seeing it. Prove it was really happening. You were the ATM camera in an episode of a crime procedural that, thank our beneficent Lord, caught the crime from an angle unlike any other, a point of view necessary to close the case, book the perp, lock them up. A deus ex machina in the form of a perspective no one knew existed, that no one knew you had. The luckiest possible break in the trickiest possible case. You couldn’t wait. You couldn’t wait for them to call you. You couldn’t wait to see the looks on their faces. You couldn’t wait to be vindicated. To be right. To stop running.

18

Destiny Fagbohun 18 19

Sitting on a Granite Boulder Beside a Pond in Maine

Feeling something tickle my cheek and brushing it aside, I send a daddy longlegs on a death-defying ride and am myself surprised to find him traveling down my thigh, sticking his feeler leg out front, the way my sister used her cane, sweeping and tapping a shoulder’s width from right to left and back again. Like her, he is an amputee: she lost a foot, he gave up three. Surrendered in the heat of battle, his legs kept twitching, bewitching his foe, taking on a life of their own, the way a phantom pain kept gnawing at my sister’s middle toe— the one she lost before they took her foot. She called what was left her nubbin, and I’m laughing now, remembering the time she phoned to recommend it as the subject for a poem. The daddy longlegs keeps blazing new paths from my lap to the pink granite boulder and back. He can’t seem to leave me alone.

Jane McKinley

POETRY

20

21

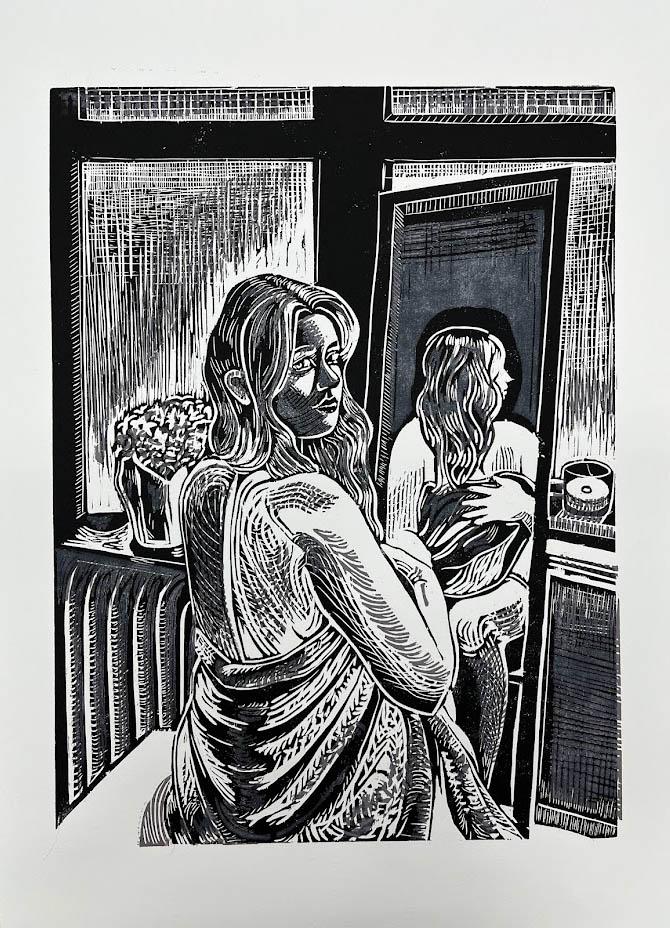

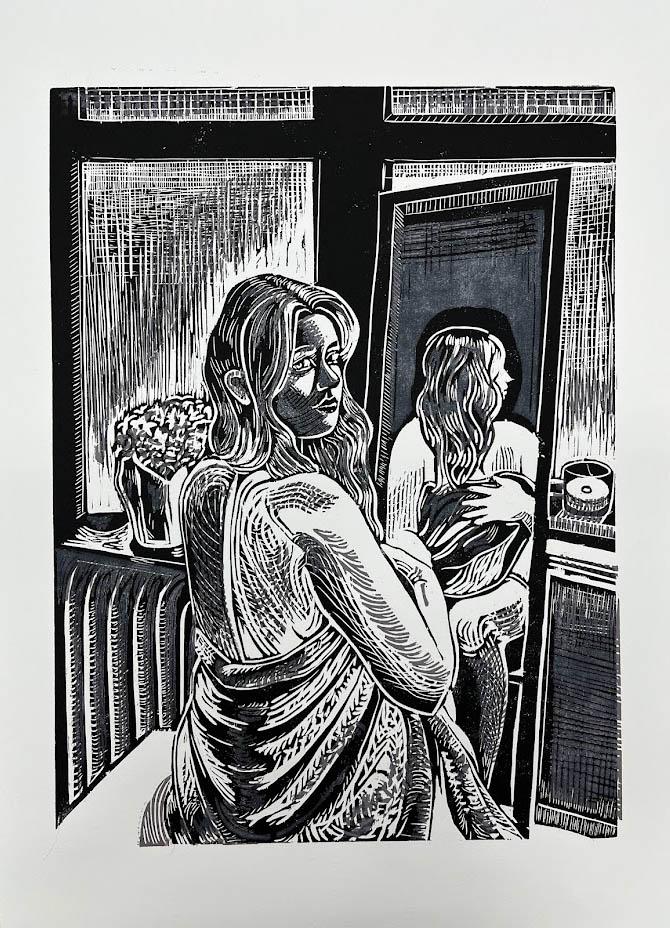

Opia Maegan Collins

She is my mother no she is my baby

NONFICTION

Meghan Proulx

There is a memory.

In the memory, a bathtub.

The tiles are white; the grout is white; the silver fixtures are gleaming without water spots. Two knees emerge from the frothy white bathwater.

A thin, swirling trail of bright pink liquid reaches out for one knee and then surrounds it. My eyes follow the trail up to the belly button. I’m scared, but I keep going up. I continue past the hollow of her chest and even further to the source of the pink. Here it is, but red now, not pink. Not diluted by sudsy water. The wounds around her eyes are weeping blood and mixing with her tears. They fall steadily from her brown eyes—the brownest brown, like nice, warm dirt.

She is my baby. No, she is my mother. But when she’s hurt or sick, she is my baby. But is she hurt? No, and she’s not sick either. But she went to the doctor and now she’s come back. The doctor made neat incisions on her eyelids. He’s a professional. He learned long ago how to reshape the drooping skin around an aging woman’s eyes, how to ensure no puffy scar tissue is left behind.

Now her face is black and blue, and my dad is embarrassed. It looks like he hit her. No, it looks like he didn’t tell her she was pretty enough. No, I saw her looking at herself in the mirror. I saw her, clear as the glass door that slides along this tub. She tugged at the loose skin under her eyelids, over and over again, pulling it taut with her tan fingers. I sat on the lip of this same bathtub and watched. I saw something I wasn’t supposed to see. I couldn’t understand at the time, so I stored it in my brain like a nut for winter.

Dear self, I see her in the bathtub. Yes, there she is. Now I know what she was thinking. Now I know what she thought of her face. She saw time printed on it. But it was time we shared together. She wanted it erased. She is my mother, and she is my baby. And like a baby, I’m confused.

When the bleeding stops, and the bruising fades, it will still be her face; it will always be her face. It will be right there, and I could hold it in my hands if she let me. I could touch the skin, and this would be proof she is still my mother, my baby.

People will say she looks ten years younger, maybe even twenty. They will ask if the two of us are sisters. It doesn’t matter if they’re serious. She will blush, and little pieces of my heart will get caught in my throat, like when you run your fingers over broken glass and little shards of it get stuck in your skin. It only hurts for a moment, and doesn’t she deserve to blush? To feel the heat rise to her cheeks? It’s her body and her face. Her pieces of skin to throw away. But she’s my mother, and I’m her baby. And if I could keep every last droopy piece of her in a locket by my heart, I would.

22

23

Focus on Fabric Maegan Collins

Being Dad POETRY

Michael Mark

I am putting my father on autopay. Rent, cable, credit cards, pharmacy, gas and electric, Medicare. Soon he won’t be writing two checks because he forgot he mailed one already, or have to pay a late fee because he didn’t send one, or call me to ask if he wrote them, or call whatever service to ask if they received payment. Life should be easier on autopay for a 96-year-old and his 65-yearold son—which somehow adds up to me still being a boy. Once on autopay, there’s no going back. Look at autopay then look at autopsy. Now look at him. Now look at me. In order to officially set this up, I pretend to be Robert S. Mark

on the phone with the companies. I have his authority. He trusts me until he doesn’t. Until he has to. I have to be loud because Dad is practically deaf, a Slow–Loud–Angry talker. And I am, it seems, a method actor. I work his Bronx accent, his 3-packs-of-filterlessesa-day rasp. No one’s questioned me asked if I’m really him yet. From the other room Lois yells, “You don’t have to roar like a wounded lion!”

She thinks she’s talking to Michael.

24

Maybe it’s respect—why I do this the way he would if he could hear, keep it all straight, wasn’t so tired. Maybe it’s mourning, pre-mourning. I don’t know. If you want to know who your father is at 96-years-old, list his 27 medications to the Medicare pharmacy representative. Let your tongue whiten from each syllable’s chalk. Say, “Rosuvastatin, 40mgs, for high cholesterol, once in the morning.” Say “Glimepiride 1milligram for diabetes, once in the morning.” Say, “Rephressor Two drops in each eye once in the morning, and once at night for glaucoma” so they can hear you at the other end of the planet and you can hear enough so its undeniable and dumbfounding and sad that you’re still here, in the shape you are. Ask, “Are you sure?” after they say, “Yes,” they have your correct information. Ask, “Are you sure?” when they tell you if each drug is or isn’t insured, tell them, “Check again.” Ask, “How much is the copay?” Say, “I can’t hear you.” Ask, “Are you still there?” Say again, “Say that again, my hearing is bad.” Ask, “Can you speak slower?” Say, “That’s still too fast” Say, “Hold on, I need my other glasses—the words on these bottles are too small.”

Say his Social Security and Medicare numbers so often you memorize them when you don’t know your own. Say, “How lost it is to be living in a world, a body, so long and be outside of it,” even though he’d never say those last words. But if you want to know your father at 96-years-old, you will, Slow–Loud—Angry, say them for him.

25

26

27

HOWL Karly Hou

THE SKULL OF AN UNNAMED AFRICAN BOY

FICTION

Stephenjohn Holgate

And the same day me turn up to start school, Malcolm turn up as well. Malcolm take one look at me, in me regulation jumper and hand-me-down trousers, sleeve, pants, foot—them all too long for me,—and decide to not even fart in my direction. For the rest of the day, more than that really, I was invisible to him.

All of this before either of we open we mouth and start talk. Now you have to consider, I just reach from back home. You could smell the mango and sunshine on me. So when I start chat, everybody staring with them mouth open and thing like that. Them never see one Indian West Indian before, you understand. Well Father, is one piece of foolishness break out, because one person come talk about if me pretending, and next one ask me if me is not a “Paki.” You have to understand, I didn’t have no idea what that mean, and if he did say it to me a week later, I would have lick him down on the spot.

I tell the whole class, No, my name is Junior and I just reach from Saint Mary, Jamaica, last month.

And I take my seat.

Well, after that was Malcolm turn to introduce himself to the rest of the class. Is then I notice him holding a briefcase, and I wonder, What the backside him doing with such a thing? As if him is a lawyer or doctor or something. You have to remember, the two of we about thirteen years old.

Hear this now, Malcolm open him mouth, and him sound just like the prince of Wales. This get a bigger response than me and my little accent. The silent shock turn into whispers until that roll into one piece of laughter and madness. I sure they don’t even hear that Malcolm say he is a serious student, that him looking forward to learning in this new environment. New environment! The boy sound like him just arrive for a job interview. Malcolm don’t say nothing about where him come from or which school him move from nor nothing like that. Still is one piece of bangarang that make everybody forget about me, so I did kind of grateful.

Little time pass now, and we settle into the place. True, I did have to thump a few a boy in them mouth when them use that P word on me. Then them try out the N word because them so ignorant, and I have to break off my foot in a few backside so them know how to behave right. Imagine. And me a full-blooded coolie and everything. But then prejudice is a kind of foolishness, you understand?

Still, wasn’t nothing like the grievousness that Malcolm did have to deal with. It start off with two people calling him Prince Malcolm. Well that must did sound too nice, so them move on to Lord Blackman, then Mister Posh, King Black, and so on. It’s not like Malcolm have any of the black people on him side neither. The

28

whole time him refusing even to be seen talking with a black person. So all the black children calling him things like coconut and bounty and Uncle Tom and unseasoned chicken, until one youth who just reach from yard call him Black-Head Backra. After people find out that backra mean white man, that was that, and Malcolm get the name that last and last.

And the whole time, there’s me looking at Malcolm and thinking something definitely not right with him. Don’t matter how him clothes fit, how them seem tailored, how him always look correct. Don’t matter that in maths class is me and him always come first and second. Don’t matter that, whatever else going on, him could run a hundred yards faster than anybody else. And it don’t matter that him wear a blazer at all times, no matter how times hot, not even when the English summer heat come and start make you sweat out of your eyeballs. No, the whole time we in school me feel as though is something else going on, something else all the strange behaviours covering up. I know Malcolm hiding something.

Check this now, one day at school somebody come up to me and say, Prove you’re not one of them. And him point to a couple of Pakistani youths who was playing football in one corner of the playground.

Eat this, the boy say and him hold up one bacon sandwich near me face. I nearly vomit. I say to him, No, I am an Adventist. I don’t eat swine.

Well, this idiot boy don’t know what this is, so him call me a liar and all sorts of names and then turn to Malcolm and say, Can you believe that they don’t eat pork? What’s wrong with them?

Malcolm take one look at this boy and say clear as anything, I don’t eat unclean animals, either.

And just like that him take off and gone elsewhere.

Me did think that was a strange response. Very, very strange, if you ask me. But you don’t spend much time thinking about these things when you young.

Two twos and the thing with Malcolm left my mind and I off playing football. Before long I fall into a rhythm with some of the other West Indian and African boys at school. Normal school life and thing.

At the same time, I was serious as anything about the studying. I was going to turn a lawyer by any damn means necessary, so I was ever reading book and working. Chance did have it that Malcolm was a bit like me in that way, working like hell to get the best grades possible. Turn into a competition before long and after we take GCSEs the two of we come out with the top grades in the school. And so it come to be that me and him doing the said same A Levels: history, politics, and economics.

But by then, I did have a little bit of information on Malcolm. One Saturday in church, not that long before we start A Levels, was a visiting pastor who get up and make a speech about how people must stop listening to devil music and dressing in certain ways and all other kinds of horse dead and cow fat. How the way we speak affect the way we behave. How we must give up with the boogooyagga ways of talking like we come from a jungle. All that kind of thing. What you call it? Respectability politics. One problem is that the pastor have the thickest accent I ever hear in my life and every other word is patois. Like him can’t follow him own advice.

Me ignore this man message completely, because I did think I was being a good enough Adventist by observing Sabbath and coming to church. I didn’t know what listening to a bit of dancehall and talking patois had to do with anything. Wasn’t none of pastor business.

29

Come to the end of the service now, my mother have to go over to this man and tell him how much she agree with the things him saying and how much she like the service and if him have any ideas to get her children to learn them book, especially the good book, the way them know the latest song. Foolishness really. I just want to leave, but that wasn’t no option and when we go over, who standing next to the pastor but Malcolm.

I nearly buss out in one piece of belly laughing because as him sight me, him two eye get big and wide like full moon and at the same time him start squeeze up him mouth like him sucking one of them sour sweetie. I know him face telling me not to say nothing. I crack a quick smile in him direction and don’t say nothing. Everything make sense all and a sudden. Malcolm living up to him father ideas about how young people supposed to live them life. This pastor with him rules and regulations and reasonings. The precision of the clothes, the Queen’s English, the blasted briefcase. Everything is him father idea, and Malcolm not allowed to be himself in any way.

When I next reach school, I know that Malcolm expecting me to say something. But I keep my mouth shut. What telling people about Malcolm and him father going do for me? Nothing. I figure Malcolm have him own problems and best thing is if I keep out of him business.

Still, every day Malcolm looking at me with something like worry in him eyes.

Time pass and, boom, we reach the end of the first year of A Levels. Summer term, and the teachers done give up on teaching we anything useful, so is pure foolishness filling up we time. Apart from the economics teacher who setting pure work every lesson. The politics teacher take we to the Houses of Parliament and that did nice, although the whole place look like it might drop down any minute.

As to history, them decide we need to go to some museum or other. I can’t even remember which one, though I know it wasn’t one in the city centre because we did have to take a coach. Was nice all the same; you could watch the city dissolve into countryside and turn into town and village. Give you a sense of the country as a whole, you know? Especially as I love the countryside because it remind me of back home. All that green. The whole time my face press up against the glass, looking at field and buzzard and hedge and wheat stalk and all sort of thing.

One piece of noise on the coach all the way there because it feel like a party the way the sun shining and the fact that we don’t have to do no serious work. Just go and look on some things about this country from the sixteenth and seventeenth century. The only person not smiling and carrying on is Malcolm—him have the same damned serious face on as ever, and the whole time me wondering if him just upset that him not sitting in a classroom writing essay.

I tell you, Malcolm look real funny as well. Everybody else in T-shirt, shorts, summer dress, and vest. But Malcolm? Malcolm in wool trousers and long-sleeve shirt. Malcolm wearing tie and have a light blazer draped over him lap. And not a smile don’t cross him face one time from we sit in our seats.And is noise and laughter the whole time with people sharing food and popping big laugh. But Malcolm trying not to sweat in him heavy clothes. Malcolm staring straight ahead and not even looking out the window. I did really wonder about that boy.

Well massa, we reach the museum and come off the coach and get all the bags them checked as we walk in. Inside is the usual collection of dinosaur bones and old crockery from the Roman times. When I check, the two history teachers them

30

nodding them heads, and one stroking him beard, and the other one have her pencil in her hands and making notes like madness.

Me take myself and walk off because my parents done fill my head with enough dinosaur and all that kind of thing from long time. Every month we used to have to go to museum and then, when we reach back home, I have to write report for them. Every damned thing had to be a learning experience. You couldn’t even sing a song without them asking you to use that energy to clean your room or if you know your English book as good as you know them lyrics there.

Sake of this I know you going to have a bag of painting of some dead white people, some old, dusty frock and a piece of paper telling you the history of the frock, some old sword, a piece of Roman flooring if you lucky, and old-time money. Nothing them museum people like more than putting old money in a glass cabinet.

And all that foolishness was there. One painting of some old-time white people with them dog, one frock from the time of Shakespeare, one buggy rich people used to drive around in. All that sort of thing.

Walking between the different rooms and seeing the things them think good enough to put on display for people, I catch sight of Malcolm. Malcolm standing in front of one big painting. This painting have a bunch of children running about— cavorting and gallivanting, as my mother would say—a couple dogs, one sternlooking man in a morning suit holding a hat and whip, and a whole menagerie of other animals. Peacock and puss, chicken and hog, a ferret looking a bit confused. And at the back in a doorway, almost completely covered in shadow, is an old black man holding some bellows, like him just start one fire somewhere.

Well, make me tell you, is then I notice how Malcolm squeezing up him hand. Making fists and then releasing him fingers. I walk over to see what happening. Usually at these things, Malcolm nose-deep in answering all the questions on the worksheet that teacher give us to complete.

Not today; instead Malcolm talking to himself. And not with him normal voice. The English gentleman gone completely, and Malcolm sounding like one of we. Like him just stop off the airplane from yard. Him muttering about backra, bloodclaat, and bandulu. Malcolm looking like him don’t know where him be.

Is then I notice a little skull them have in front of the painting. And next to that, one little card that say: Here is the skull of an unnamed African boy. He may have been a servant in a wealthy family’s household. This skull was kindly donated by the Colston family.

Malcolm still there muttering to himself. Saying things like, How them could take one pickney head and just put it inside one case like that.

And, Is who the rass them trying to fool?

And, What them mean by servant?

A few people start gather around by this. Not many black people in this museum, and certainly none who talking to themselves and crying. Yes, by this, tears rolling down Malcolm face! Big, fat tears. The ones them you can’t hide. This cause more people to gather and when me take a look, is a older woman attendant coming over to us to see what happening.

But hear this, is now excitement start! The woman come put her hand on Malcolm shoulder and say, What’s wrong, dearie? Then she put her hand on him head.

31

Without missing a beat, Malcolm say, Don’t bother come fingle-fingle me like tomato in a market. People like you always think this sort of thing alright.

And I see the woman break out a smile, but is not a nice smile. It wasn’t no smile you expect to see on her face. She have one of those sweet old lady faces, like she going to offer you a cupcake or one sweetie. Instead, she open up her face into this smile that look like it about to eat you up, and she say, And you people don’t belong here, do you? Always causing trouble. Don’t know your rightful place in the world, much less the gallery. Always wanting special treatment.

When I tell you, I wasn’t expecting her to say that. And to Malcolm as well. When him did already look upset. Malcolm look as though somebody slap him on the side of him face. But before either one of we could say something, the woman whole face shift and she start look frightened. She reach for her walkie-talkie and say, There’s a young black man causing a disturbance in the upper gallery. Someone send security; he won’t listen to me and I’m worried he might hurt someone. Help! He’s acting erratically.

I hear enough. I grab Malcolm by the shoulders and tell him, Run.

And we tear off through the gallery, past postcard and ration book, through the art section with a whole heap of painting of hillside and field and pebble beach, down the stairs, and into the learning area.

All around we is chalk and table and paper and costume from the nineteenth century. I struggling to catch my breath by this point, but Malcolm just standing there, looking about as miserable as could be.

Then him start talk, not really to me, just out loud, and say, You could imagine, Junior? You could imagine that you have to serve these people and you life mean so little that when you dead, they don’t even give you a name? Just the skull of one unnamed African boy. A servant? And then them don’t even make you rest in death. You slave for these people til you wear out you body and dead, as a pickney, not even as a big person. And then them take you head and polish it and shine it up and turn into figurine for people to come look at. And at the end of it all, as if to excuse the whole damn thing, them put up one little placard nearby talking about how Britain abolish the slave trade. Who did start it, Junior? Who? Not me? Not you? Neither one of we grandparents or even the grandparents of our grandparents.

And I nearly say, I know how you feel. But that wouldn’t did right. I don’t have no idea how Malcolm feel. Him black and me brown. Him look African and me look Indian. I don’t have no idea how him feel.

As I think of what to say, I see two security guard moving through the place. I know them looking for the two of we, because the woman must done say one coolie boy help the black boy escape. I drag Malcolm round the corner to where them have a little dress-up area. Red soldier outfit, milkmaid dress. All that sort of thing.

I turn to Malcolm and say, Malcolm, I would like to listen to you a little more, but we need to get out of this situation first.

And I tell him to put on one of the frock them, and I going dress up like a soldier, and we going walk straight out of the museum.

Malcolm start twist up him face and say how him don’t want to be involved in funny business and all that sort of foolishness. In the end I say, Alright Malcolm. The two of we going to put on dress and walk out. Them look for two boys, not two girls. That make you feel better?

32

Malcolm grunt something I take for okay, and we put on the dress them quick. Malcolm even grab one parasol to help cover up him face, and we start walk towards the exit. One piece of sweat break out over my body. The day hot, and I nervous like anything. For some reason, Malcolm skinning teeth like him enjoying himself, and I suddenly feel to pop one belly laugh which I have to quickly swallow so we don’t get catch.

We walk right past the security guards and even the old lady. Them look cross and miserable, and I wonder how them would have treated Malcolm if them did catch him. Not like I don’t see foolishness on the news of what happen to people who look like Malcolm. I can imagine and it make me shudder.

As we near the front, we peel off the frock them, throw them next to a display case, and head straight out the door. We almost run into the coach. Me and Malcolm not saying one damned word to each other. Just heavy breathing and staring ahead until other people come back for the drive home.

We sit next to each other on the journey back to the college. While is a few eyebrows raise up, and even a few people looking hard at we, nobody don’t say anything. And neither me nor Malcolm don’t say a word as the coach crawl through the countryside and toward the grey city that we was now calling home.

33

34

A Tree that a Monkey Cannot Climb (Maumun Çıkmaz Ağacı)

A Tree that a Monkey Cannot Climb (Maumun Çıkmaz Ağacı)

35

Julia Prikhodko

An Analgesic for the Antichrist

FICTION

Brett Hymel Jr.

One night during dinner, my brother decided to stop talking. He delivered this announcement on the gravy-stained, threadbare fabric of a napkin folded three times in on itself. Little showers of crumbs cascaded from hidden crevices as my brother passed the napkin to my father, who took it with solemnity and began to wipe at the whiskered corners of his mouth.

“No,” I said, “He’s written something on it. Look.”

My father laid the napkin across the center of the table, shifting a bowl of peas as he did so. Streams of peas cascaded toward the edges of the bowl.

The letter read: “My medicine is missing. I have reason to believe it was taken. In the past two days, Satan has returned to me again. Through the walls and floorboards, he comes to me in hidden, empty spaces—a dark closet, a baby’s yawning mouth. If I don’t receive my medicine within one week’s time, I’ll never speak again. Love, C.”

My brother stood up, scraped the rest of his meal into the garbage, and set his plate on the enormous mound of dirty dishes that resided in the center of the sink, plates and trays laid one on top of the other like those little Russian nesting dolls. In my family the tradition was to deny any claim to this quivering Jenga tower of filth, spent oil, and dirty bits of tomato sauce. Everyone pleaded ignorance until somebody got angry enough to clean all of the dishes in a neat little fit of productive rage. Who did these dishes belong to? They were everybody’s, and so they were nobody’s.

My brother ran the garbage disposal just to hear the metallic pleading noise it made. From the base of its throat, it conjured a perverse, guttural rattle that made me feel both sinful and ashamed, like I had accidentally stumbled into some stranger’s hospice death. My brother pressed the button and the noise abruptly cut off. He disappeared up the stairs.

“Garbage disposal needs fixing,” my mother said. She always spoke in code. Three decades of aggressive reminders to brush my teeth and wear the right clothes to church had taught me the cipher. This is what she really meant: Is this pledge to stop talking a serious undertaking?

“Listen,” I said to my parents, “This whole talk of muteness is bullshit. This is a petulant and chaotic boy you’ve raised. Do you remember when he was three and I was five? When he was three and I was five, he shoved me off the scooter. He went right up to me and shoved me off the scooter and I fell and dinged my knee very badly on the driveway. I’m better now, and I’ve put it in the past, but some things tend not to change. Now he’s twenty-eight years old and he still enjoys the discomfort he can instill in our souls.”

My father picked the note back up and wiped at the corners of his mouth.

36

The day after the announcement was a gray, tepid morning. The sun huffed diffident rays through the fog outside. We were in the kitchen eating yogurt and pears for breakfast, the fruit fresh from the garden. Some people will claim that any apple is better than even the best pear, but these people are victims of a mental illness—one that allows them to say anything and believe they’re always right. What is that illness called again?

“Growing pears,” my father said. “This is a man’s work.” He brought a spoon of yogurt up to eat and missed his mouth by a mile. “Creating messes. Nothing manlier.”

My brother came down the stairs. He was holding his knife in his hand. It gleamed from all angles. I saw his reflection in the polished metal.

I know what you’re thinking. You’re thinking we probably should have taken the knife away from the mentally unwell man we lived with. All I can say to that is this: you try separating that boy from his knife.

My brother walked over to the kitchen island and scratched a deep, long scar into the beadboard. The knife made a sound like an army of geese, like every car alarm in the garage going off at once. He turned to us and held a silent, trembling finger in the air.

“We see the tally mark,” I said to him. “The finger is superfluous.” My brother gave me a different, more special finger and walked back upstairs.

“There’s more yogurt in the fridge,” my mother called up to him. Translation: My son has begun to count the days to eternal silence, and I find myself afraid.

On the second day, I walked into my brother’s room without knocking. My brother hates visitors. He claims visitors leave a trace of their souls in the spaces they occupy, and my brother is opposed to this spiritual cross-contamination. Aristophanes tells the myth of two humans joined together to create a being so powerful that the gods were threatened by its very existence. I have a simpler explanation: my brother hates to clean up after people.

He was carving sudoku puzzles into the wall, long straight rows of empty spaces awaiting the ingestion of digits. He paced back and forth trying to solve a certain portion of the puzzle, a confluence of squares that refused to yield a happy result.

“I’m glad that Satan is giving you mentally stimulating exercises,” I said. My brother didn’t respond. He was marking the boundaries of his room by the length of his strides. I knew how large the room was; I had seen the housing blueprint. It was fourteen by fourteen, two feet longer than my room on either end. I wasn’t upset about this. I used to be a jealous person, but not anymore. My therapist told me jealousy was like a bad haircut: you had to wear it with you everywhere. I loved my therapist with all my heart. I trusted him with anything.

“Have you considered psychoanalysis?” I asked my brother. My brother carved a six into a vacant square on the sudoku board.

“Let me say this: I love my therapist with all my heart. He knows everything about me, from my drive-thru order to my Myers-Briggs type. We sit in his office and answer surveys. Did you know that surveys are an analgesic for the antichrist? Forget your pills, when’s the last time you were on BuzzFeed?”

My brother carved another six into the wall.

“The only strange thing about my therapist is that he asks me the questions in an accusatory way. He’ll say, for example, ‘You believe in the power of a hot bath,’ or

37

‘You are opposed to the principle of asceticism on primarily moralistic grounds,’ but he makes it sound like a foregone conclusion, like he’s reciting a fact. It’s not his fault. English isn’t his native tongue. He doesn’t understand the way the inflection works in this language. I think he’s from somewhere in the Mediterranean. He has that sort of complexion. Is Macedonian a language, or is that strictly just an ethnicity?”

My brother carved a third six into the wall.

“That’s not how sudoku works,” I said. “It needs to be distinct numbers on each line. You’re breaking the rules.”

My brother didn’t respond. He was trying to sort through his puzzle. My therapist made Myers-Briggs accusations in my brain.

You are a keen steward of your cardiovascular health.

You have a little voice in your head that tells you right from wrong.

On the third day, my brother sat at the kitchen table doing woodworking. He was using a fine grit sandpaper to smooth down some sort of mechanism, taking periodic notes in a journal as he went along. I stood on the stairs a moment trying to see beyond the hulk of his back. My brother had broad shoulders. He was constantly exercising. When he shifted, I saw what he was working on. He was constructing a tiny guillotine.

The sun bit through the fog and scattered it, sending little tessellations of light across the mountain of dirty dishes. My father walked in from the yard, dribbling pear juice down his chin like some kind of enormous toddler. He checked the heft of the guillotine and ran a finger along its beveled edges.

“Woodworking,” he said, “I can’t think of a more manly thing.” He patted my brother on the head.

My brother bent low to the guillotine so that his eyes were level with the blade. It shimmered and sent a long, thin finger of light across the floor to where I stood. I watched my brother, my mouth dry, my hands slick with sweat. He stuck out his tongue and laid it on the bed of the guillotine. The organ was red and wet and alive. The only thing separating it from the blade was a length of rope, four tallies, and a little bit of willpower. My brother made a note in his journal.

You take a healthy interest in your daily horoscope.

You participate in low-effort collectivist movements: recycling, returning shopping carts.

On the fourth day, we tore the house in half trying to find the pills. Furniture was rearranged in bizarre interpretations, feng shui euthanized with clinical indifference. The dining room became a haunting ground for coupon booklets, the foyer a reunion party for missing socks—Nike, class of ’03, superlative-winner for jism absorbency. Only when each fragmentary article was laid out and tagged for record-keeping, like some sort of true-crime fever dream, did we truly begin to despair at the magnitude of the operation. My mother shook her head forlornly at the piles of useless junk. “Water, water everywhere, and not a drop to spare,” she said sadly. Translation: the pills weren’t in the fucking house.

My father entered the foyer wearing a pair of sod-caked overalls. I liked to think he went outside just to roll around in the dirt. He saw our stricken faces and asked what was wrong.

“The pills aren’t here,” I said.

38

“Well, shit,” he replied. “Why don’t y’all run up to the druggist and get another bottle?”

My mother and I looked at him. I cleaned scum from inside my ears. “What?” we asked.

“Another bottle of pills,” my father repeated.

This was the situation: my brother had been taking sugar pills. It was a brand called Placebo-Lite that was stocked at the local drugstore. At some past zenith of my brother’s mania my father had driven to the pharmacy and asked for a cure to Biblical plague and spiritual malaise. The result was a tidy little bottle of whatever the heart desired it to be. All my father had to do was remove the label.

This time when we went, however, we had no such luck. The pharmacist at the counter told us about the discontinuation of Placebo-Lite. “It’s a matter of nobody wants to believe in anything anymore,” he said. “It’s an instance of people needing facts and metrics. They ask me for a chart with a line going up or down. How does science work? Can we distill the apothecary’s magic into a series of neat little pictograms, an ad taking up no more than thirty seconds of TV airspace?

Kierkegaard’s leap of faith.”

“Was that last part supposed to be an answer to your question?” I asked him. But he had directed his attention to the sudoku puzzle he was working on. I could tell that he was winning, insofar as such a thing can be won or lost. The victory is against oneself, a struggle against the constraints of the mind.

You take special care to avoid trans fats.

You would write a holiday card, if only you had someone to receive it.

On the fifth day, I woke from a cold, dreamless sleep to a loud crash. I walked downstairs and found my brother scooping a plate into the dustpan, the fragments of ceramic glinting dully under the overhead light. The sink’s faucet was running, and a mound of fresh plates had been set aside. My brother was in the middle of washing the dishes. His anger had boiled into productivity.

“I’m glad that Satan is having you do chores,” I said. I bent down to help him gather the shards into the dustpan. He hit at my knee with the flat part of his hand. His palm made a dry, hollow smack against my skin.

“Don’t fucking touch me,” I said to him. I straightened and then I froze. I could finally see the garbage disposal, its toothless grin, the vacuous cavern of its wet, gaping mouth. There was something lodged inside.

My mother came into the kitchen carrying an orange husk. It was tattered and warped, parts of the downy fuzz sullied by decades of dirt and dust. “This is the costume from your first Halloween,” my mother said, laying the carcass at my brother’s feet. “You were the sweetest pumpkin in the patch.”

What words can possibly translate this inarticulate and futile statement?

On the sixth day, my parents gave up. They sat and ate dinner in silence and would not look at my brother for fear of crying. The fog strangled the light from the window and nobody motioned to switch on the overhead lamp. Things were dim, and a damp chill had seeped in, a chill that cut to the bone. The guillotine sat in the center of the table surrounded by a little bed of wood shavings.

My father rubbed his chin thoughtfully. “Cuttin’ your tongue off with a tiny guillotine after you fail to reconcile psychic trauma,” he said through a mouthful of

39

peas. “Is there a manlier thing on Earth?”

I wasn’t impressed by any of this, however. I had seen my brother’s secret. I stood and walked over to the sink. The whole room had grown desperately cold, and I trembled through the thin fabric of my shirt. “You’ve always been a petulant and chaotic child,” I said to my brother, putting my fingers into the sink. “Do you remember when you were three and I was five?” I reached into the wet, gaping mouth of the garbage disposal. “When you were three and I was five, you shoved me off the scooter and I fell and dinged my knee very badly.” My hands closed around the bottle. “It’s fine now, I’m over it. I used to be an angry person, but I’m not anymore. Now I’m healthy. I’m everything I ever wished I was.” I pulled the bottle of Placebo-Lite out of the garbage disposal and held it up so my family could see it. The label was gone and the plastic bottle was now coated with mold and slime. Can a thing ever change its form, or does it only grow more and more desperate as it withers away? There were still pills in the bottle, quivering like the false teeth of an anxious old man. “What were you hoping to accomplish here?” I said to my brother. “Why didn’t you just flush it down the toilet, if you wanted to act crazy?”

My brother was silent even as he jumped on me. I was knocked backward by his weight and fell into the cabinet. My head hit the wood. I gave a muffled cry. My brother landed on top of me and began to hit me with a balled fist. Each hit landed on me like a terrible and suffocating weight.

You would attend a cooking class for the right price.

There was sawdust in my mouth. I felt my tongue turn to paste, as if it might fall off. I shoved my brother hard and he rolled off of me. Panting, I picked up a freshly cleaned glass. With all my might, I brought it down on my brother’s head. There was a heavy noise, like an appliance being dented. The glass chipped but did not break.

You believe in the transformative power of yoga and other stretching exercises. My brother staggered to his feet and kicked me in the nose. I felt something in my face shatter in an irreconcilable way and tasted the hot blood as it ran from the remnants of my nose into my mouth. I got to my feet, my head reeling. My brother stood panting in front of me.

You have always been a miserable little shit.

With all my might, I shoved my brother. My parents leaped out of the way. My brother careened backward into the table, the legs wobbled and gave under his weight, and dishes came cascading down around him, breaking in tiny, tinny showers of glass and ceramic. Peas ran in rivers over the upturned edge of the bowl, scrambling across the floor. The guillotine traced one terrible, delirious spiral toward the ground and hit the tile. The rope came loose, the blade came down, winking in the evening glow and, quicker than a thought, my brother’s right pinkie finger lay amongst the splinters and sawdust. My brother looked from his hand to where his severed finger sat. He rolled his eyes in an uncomprehending way and shook at his hand, as if trying to rid himself of an itch. A slow and terrible realization crawled across his face. With all the force of his lungs, he began to scream.

You are the puzzle on the wall, the scum that lines the bottle of pills. You reside in empty spaces—a dark closet, a baby’s yawning mouth. Your brother screams and screams, but you are so shy, you can’t form the grace of a simple I love you, the tenderness of I’m sorry. That tongue of yours is so useless. Cut it off, and find some better way to fail the people you love.

40

41

Jay Daughtery Caveat Emptor

Why the Town Water Tastes Like Cigarettes

FICTION

Brigs Larson

It’s bigger than they really need, isn’t it,” Tom says, as if we haven’t talked about this a thousand times. He taps the steering wheel, trying to get out energy that won’t leave him alone. At least he hasn’t smoked today.

“Too big. How’d they even afford it?” I ask. Tom shrugs. I shrug.

We sit in silence in his Ford Escape and stare at the Dooleys’ house. It’s what we do on Fridays now—he picks me up, we drive around listening to his shitty music, and we end up in front of the Dooleys’, trying to see what they’re watching for Friday movie night, craning to catch a glimpse of Mr. and Mrs. Dooley fooling with the curtains open like Tom says he saw once. They always close their curtains, but he swears he saw them. I’ll never believe him.

“I went inside once,” he says, and I tear my eyes away from the second Lord of the Rings they’re watching in the living room. Aragorn is pushing open the doors of Helm’s Deep, framed by two manicured hedges outside the picture window. They put a Christmas tree in that window in the winter. Glitters like anything.

“No fucking way.”

“Way,” Tom says, and from the glint in his eye I can tell he’s telling the truth.

“When?”