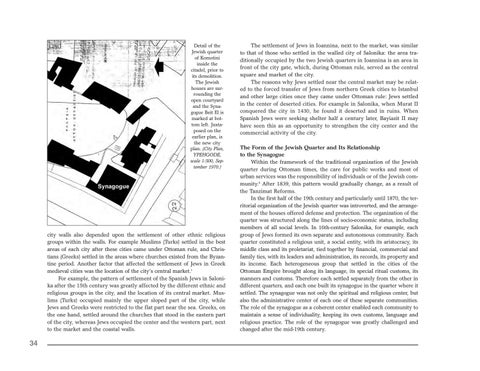

Detail of the Jewish quarter of Komotini inside the citadel, prior to its demolition. The Jewish houses are surrounding the open courtyard and the Synagogue Beit El is marked at bottom left. Juxtaposed on the earlier plan, is the new city plan. (City Plan, YPEHGODE, scale 1:500, September 1970.)

city walls also depended upon the settlement of other ethnic religious groups within the walls. For example Muslims (Turks) settled in the best areas of each city after these cities came under Ottoman rule, and Christians (Greeks) settled in the areas where churches existed from the Byzantine period. Another factor that affected the settlement of Jews in Greek medieval cities was the location of the city's central market.1 For example, the pattern of settlement of the Spanish Jews in Salonika after the 15th century was greatly affected by the different ethnic and religious groups in the city, and the location of its central market. Muslims (Turks) occupied mainly the upper sloped part of the city, while Jews and Greeks were restricted to the flat part near the sea. Greeks, on the one hand, settled around the churches that stood in the eastern part of the city, whereas Jews occupied the center and the western part, next to the market and the coastal walls.

34

The settlement of Jews in Ioannina, next to the market, was similar to that of those who settled in the walled city of Salonika: the area traditionally occupied by the two Jewish quarters in Ioannina is an area in front of the city gate, which, during Ottoman rule, served as the central square and market of the city. The reasons why Jews settled near the central market may be related to the forced transfer of Jews from northern Greek cities to Istanbul and other large cities once they came under Ottoman rule: Jews settled in the center of deserted cities. For example in Salonika, when Murat II conquered the city in 1430, he found it deserted and in ruins. When Spanish Jews were seeking shelter half a century later, Bayiazit II may have seen this as an opportunity to strengthen the city center and the commercial activity of the city. The Form of the Jewish Quarter and Its Relationship to the Synagogue Within the framework of the traditional organization of the Jewish quarter during Ottoman times, the care for public works and most of urban services was the responsibility of individuals or of the Jewish community.2 After 1839, this pattern would gradually change, as a result of the Tanzimat Reforms. In the first half of the 19th century and particularly until 1870, the territorial organization of the Jewish quarter was introverted, and the arrangement of the houses offered defense and protection. The organization of the quarter was structured along the lines of socio-economic status, including members of all social levels. In 16th-century Salonika, for example, each group of Jews formed its own separate and autonomous community. Each quarter constituted a religious unit, a social entity, with its aristocracy, its middle class and its proletariat, tied together by financial, commercial and family ties, with its leaders and administration, its records, its property and its income. Each heterogeneous group that settled in the cities of the Ottoman Empire brought along its language, its special ritual customs, its manners and customs. Therefore each settled separately from the other in different quarters, and each one built its synagogue in the quarter where it settled. The synagogue was not only the spiritual and religious center, but also the administrative center of each one of these separate communities. The role of the synagogue as a coherent center enabled each community to maintain a sense of individuality, keeping its own customs, language and religious practice. The role of the synagogue was greatly challenged and changed after the mid-19th century.