17 minute read

Empathizing with a Bigger World in Your Own Backyard

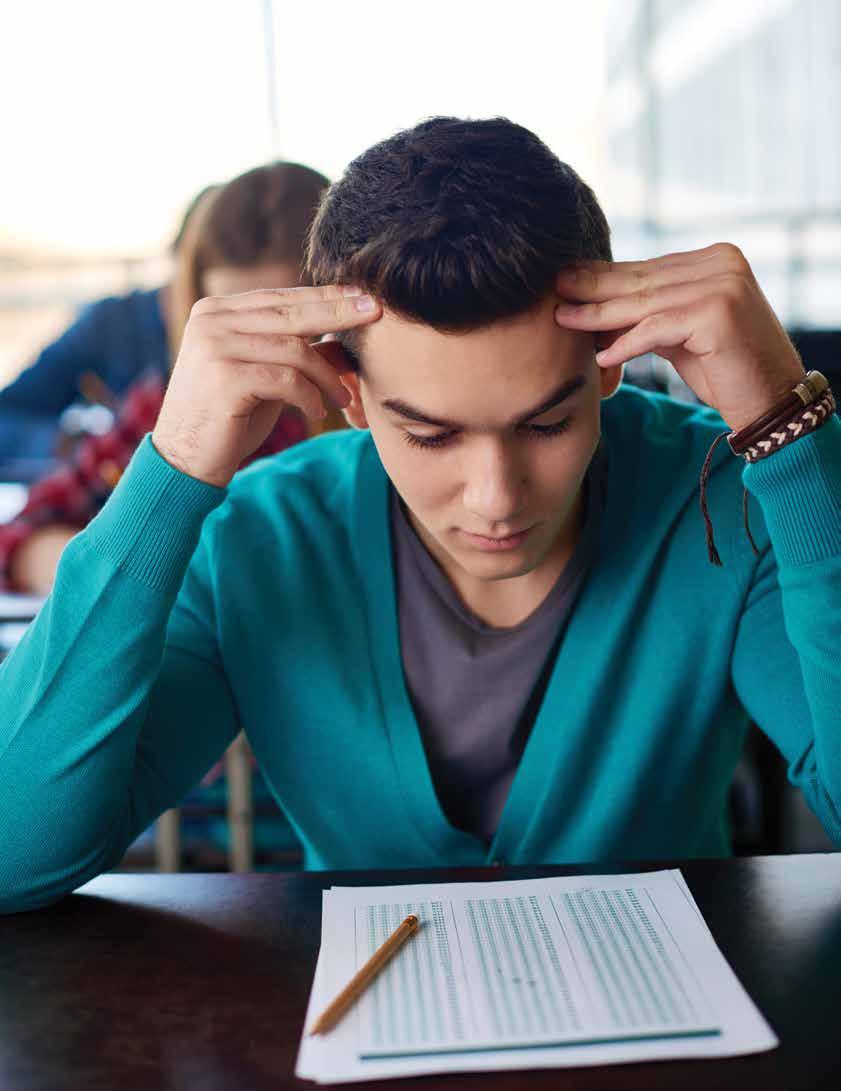

Isabella’s eleven-year-old son, James, walked in their door after school. He threw his backpack across the room and ran down the hallway to his bedroom clearly upset.

EMPATHIZING WITH

A BIGGER WORLD in your own backyard:

How Parents Can Support a Child’s Growing Social Awareness

By JENNIFER S. MILLER, M.ED. sabella waited until James finally emerged, hungry for a snack. As he searched the kitchen, she asked, “Are you okay?” James sat down with a bag of chips and explained that he was “sick of school,” or more accurately, the students he encountered. One of his long-time friends, Dakota, had been hurt by some of their supposed friends today, and he felt angry and helpless to do anything. James loved hanging out at Dakota’s house and getting to know his family – his father, a Native American of Crow ancestry and his mother, a Latina-American, both of whom grew up in Montana. Frequently he would catch his “friends” labeling Dakota. They had hung out with the same group since kindergarten, but now those “friends” were making fun of Dakota because his mother would speak to him in Spanish. He had attempted to befriend some others who labeled him “the Mexican,” when his family had no heritage from Mexico whatsoever.

Today felt like the last straw for James when he had watched Dakota fight back tears at their lockers after the group had insultingly mimicked his mother’s Spanish. Not only was he mad at the others, but he felt sick about his own role. “I know I should have stopped them, but I just stood there; I didn’t do anything,” James told his mom. He was frustrated with himself. “Why didn’t I stop them?” he uttered to himself. Why couldn’t classmates just take Dakota for who he was, a devoted student and good friend?

Clearly, the group of friends involved in labeling Dakota were struggling with social awareness and not accepting Dakota for who he was. And James, though feeling empathy for his friend, struggled to take action. He too was trying to figure out how to respond when others were treating a friend unfairly. From birth, our children are growing and exercising their social awareness, defined by the Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL) as “the ability to take the perspective of and empathize with others, including those from diverse backgrounds and cultures and the ability to understand the social and ethical norms for behavior and to recognize family, school, and community resources and supports.”

CASEL recently further defined social awareness through the lens of equity. Children I

Are you interested in helping children and families in your community? If so, please consider becoming a foster parent to those in need. Contact us today at 855-MICHKIDS (855- 642-5437) to find out how you can help. Are you interested in helping children and families in your community? If so, please consider becoming a foster parent to those in need. Contact us today at 855-MICHKIDS (855- 642-5437) to find out how you can help.

and teens are more likely to learn to empathize when adults accept and value cultural differences and discuss power dynamics that disadvantage some and advantage others. If we don’t discuss these issues with our children, we can perpetuate old stereotypes and limit growing social awareness skills.

Social awareness also includes recognizing shared interests and life circumstances. Dakota was a classmate, a friend, played on a sports team, and loved his pet dog just like nearly every other child in his class. His classmates’ mistaken interpretation of his heritage and what that meant about his identity were separating him out and hurting him and his friend.

Growing our children’s social awareness poses a number of challenges for the adults who love them. First, if we are to prepare our children for contributing to our global community, we have to recognize and admit bias. We must challenge our own thinking as we raise important questions for our children to consider. This puts us in the uncomfortable position of not knowing it all. Yet, that model of vulnerability, of standing in the face of challenge and admitting we have much to learn, will aid us considerably with our next challenge. As our children develop greater social awareness, their social anxiety rises in direct proportion. Why? As our children work to exercise their perspective-taking muscle, they make wrong interpretations about others’ thoughts and feelings. After all, we are not born mind readers. Empathy requires practice. In the preteen years, feelings of heightened sensitivity complicate this as children’s brains and bodies are dramatically changing. The preteen through teen years can feel isolating as our children become increasingly anxious about their peers’ potential criticisms of who they are. Our opportunity to show vulnerability will not only model what our children are experiencing — “It’s okay not to know it all” — but also open the door to a more trusting connection where parent and teen can wrestle with the tough questions together. There are a number of ways we can help our children and teens become more socially aware. Here are some specific ideas.

3- TO 5-YEAR-OLDS Practice physical awareness. Our young children are working hard to figure out how their bodies can cooperate with the hopes of their minds and hearts. Through pretend play, they work on their fine and gross motor skills. They are interested in learning about their own body parts and curious about others’. This is an ideal time to practice body awareness. For example, play the game “What does your body tell you? What do others’ bodies tell you?” According to The Definitive Book of Body Language, body language is five times more powerful than words! Work on identifying facial expressions, body postures, and ways of moving that communicate emotion. This focus will assist a child in noticing nonverbal cues from others.

Discuss race, culture, differences, and commonalities. Use children’s books to spur conversation. Because children are more regularly engaging in play with others, this is an ideal time to talk about differences and commonalities. There are people with a variety of skin colors, different beliefs about a higher power, and a range of traditions around the world. What can we learn from those differences? And, how many commonalities can we discover? Be sure to seek common ground as there is always more that unites us than divides us. Also, practice acting with kindness and inclusion. Model bringing others in the circle of play who were not naturally there. The seeds of exclusion can be planted at this stage; it’s critical that we offer children the chance to practice inclusion.

6-TO-8-YEAR-OLDS Act as a feelings detective. Children require practice in naming emotions in order to manage them and grow a sense of empathy for others. Create a dinnertime game to discover what Dad is feeling when we ask him, “How was your day?” Use errand runs to see if you can figure out what people are feeling through their facial expressions. When your child comes home and tells a story about classmates, ask the question: “How do you think they were feeling?” These simple games will simultaneously promote valuable selfawareness, self-management (name it to tame it), and social awareness skills.

Advance your conversations on inclusion and equity. Your child may be encountering children from other cultures, races, and abilities for the first time as they enter elementary school. Make a point of discussing race, culture, and differing beliefs and abilities whenever the topic may arise. Equate “different” with “an opportunity to learn and value” versus “weird.” At the beginning of each school year, you might ask: “How would you feel in a new school where you didn’t know anyone? Can we come up with ways that you could welcome the new students and help them feel comfortable?”

9-TO-12-YEAR-OLDS Prepare with peer tools. How do you coach your child when they encounter mean words or actions at school? Consider offering your child some simple ways to stop harm without causing more and move to safety. You might practice together saying, “Stop. You know that’s wrong (or unkind),” and then walk away. Isabella could have coached her son to help his friend, Dakota, by agreeing to walk him away when verbally attacked. Did you know more than half of bullying attempts stop when another child intervenes? Agree with friends to help one another stay safe. Then, express compassion: “You know when someone is lashing out, they are hurting inside.” Criticizing other children may put your child in harm’s way. Instead, how can you express empathy and compassion while keeping your child safe?

Share stories of fairness and justice. Children at this age are keenly attuned to issues of fairness. Build on this rising insight by discussing the complexities of acting in just ways. When friends make poor choices, ask, “What other choice did they have? How would those choices have resulted in different outcomes?” Point out ways in the larger world that individuals and cultures struggle for rights and talk together about ideas to solve those big problems. Read age-appropriate biographies together about Martin Luther King, Jr., Mahatma Gandhi, or Rosa Parks to learn about those who risked their lives for justice.

FOR 13-TO-18-YEAR-OLDS Engage in powerful conversations. Teens are ready to engage in powerful conversations about more complex issues. Movies, social media, and everyday experiences provide opportunities to practice empathizing. Asking your teen questions like: “What would it be like to be in someone else’s situation? How would you have reacted if you had been them?” Or “Have you seen examples of people being mistreated because of their race, ethnicity, or other differences? How did that make you feel? What could you do about it?”

Practicing social awareness with your child is a meaningful contribution to our next generation. Offering your child access to your own open mind and grappling with some of our world’s toughest issues of fairness and justice together will strengthen yours and your child’s empathy and compassion. You may just change the world for the better in your own backyard. ■

About The Author: Jennifer S. Miller, M.Ed., author of the popular site, Confident Parents, Confident Kids, has twenty years of experience helping adults become more effective with the children they love through social and emotional learning. She serves as a writer for ParentingMontana.org: Tools for Your Child’s Success, a statewide media campaign to educate parents on social and emotional learning. Her book, “Confident Parents, Confident Kids; Raising Emotional Intelligence in Ourselves and Our Kids — From Toddlers to Teenagers” releases November 5, 2019.

Check out who’s standing out in our community.

IS THERE SOMEONE YOU’D LIKE TO NOMINATE? Please email livingstoncouncil4youth@gmail.com and tell us why this individual has stood out in your crowd.

FACES IN THE CROWD

Ben Welch PINCKNEY COMMUNITY HIGH SCHOOL, SOPHOMORE Ben Welch, age 16, is a sophomore at Pinckney Community High School in the New Tech High program. He is the leader of the Student Leading Students group and has been involved with student-led prevention since the 6th grade. He plays the viola in the High School Symphony Orchestra. Ben enjoys spending his time with his Boy Scout Troop #395 camping and going on outings. He currently is a Life Scout and working towards his Eagle Scout Award, which he hopes to complete in 2021. He also is active serving at his church in the Emerge Student Youth group and running the tech soundboard. He also enjoys hunting, fishing, playing Xbox, and rooting for his favorite college team, The Ohio State Buckeyes.

Josh Warder BRIGHTON HIGH SCHOOL, JUNIOR Josh is a junior at Brighton High School. He takes Advance Placement classes and is involved in the Brighton High School drama productions. Also, he has volunteered his time and recruited his friends to participate in Wake Up Livingston’s Reality Tour. Josh has also participated in community theater productions that have raised funds for families of law enforcement officers that have suffered traumatic injuries. Josh is also involved in his church, The Naz in Brighton. He plays basketball and football. Josh is kind, caring, and committed to helping his family, friends, neighbors, and community be the best they can be.

Melody Denby HARTLAND HIGH SCHOOL, SENIOR The staff at the Hartland Teen Center are pleased to recognize Hartland High School senior Melody Denby. Melody has been a regular at the Teen Center for years. Melody has worked hard during high school and has been accepted to Kettering University. She is president of the Hartland High School Women in Technology Club, and she is currently preparing to compete in the Autonomous Innovative Vehicle Design Challenge. Melody is also active in the GayStraight Alliance Club, and is an advanced student in American Sign Language. Melody is already working towards a goal of designing easy-to-use software that will translate ASL to English and allow for improved communication between the hearing and deaf communities. Melody is a great leader and a true visionary.

Karen Storey BRIGHTON AREA SCHOOL TEACHER Karen Storey, Brighton Area School teacher with 20 years of service, is an educator who gives her love and devotion to the community. Currently a teacher at Maltby Middle School, Karen is now the MTSS (RTI) facilitator and the founder of the BAS Pack of Dogs. Karen has been the driving force behind the program introducing and assigning 12 dogs to various programs in each Brighton Area School, Tot Spot, and Senior Center. As the program’s founder and local educator, Karen’s goal has been for the dogs to ease a student’s anxiety, providing them with a connection to school. The BAS Pack of Dogs are owned by the Brighton Area Schools and are paid for through community dollars.

Hartland Unified Athletics Hartland Unified Athletics brings general education students and students receiving special education services together at Hartland High School. Hartland Unified Athletics currently participates in basketball and bocce against other Kensington Lakes Activity Association Unified teams. In addition to athletics, Unified team members work on school activities and events to spread the positive message of inclusion to all students. The opportunities for students to build character and leadership skills are lessons that will be carried on throughout life. The friendships developed through the program enhance the school community and atmosphere. For more information, the Hartland Unified Athletics program, please contact Hartland Consolidated Schools. #ALLIN

SUPPORTING | CARING | ENGAGING | EMPOWERING

LIVINGSTON COUNTY YOUTH

40 DEVELOPMENTAL ASSETS

40 Developmental Assets are essential qualities of life that help young people thrive, do well in school, and avoid risky behavior.

Youth Connections utilizes the 40 Developmental Assets Framework to guide the work we do in promoting positive youth development. The 40 Assets model was developed by the Minneapolis-based Search Institute based on extensive research. Just as we are coached to diversify our financial assets so that all our eggs are not in one basket, the strength that the 40 Assets model can build in our youth comes through diversity. In a nutshell, the more of the 40 Assets youth possess, the more likely they are to exhibit positive behaviors and attitudes (such as good health and school success) and the less likely they are to exhibit risky behaviors (such as drug use and promiscuity). It’s that simple: if we want to empower and protect our children, building the 40 Assets in our youth is a great way to start.

Look over the list of Assets on the following page and think about what Assets may be lacking in our community and what Assets you can help build in our young people. Do what you can do with the knowledge that even through helping build one asset in one child, you are increasing the chances that child will grow up safe and successful. Through our combined efforts, we will continue to be a place where Great Kids Make Great Communities.

Turn the page to learn more!

The 40 Developmental Assets ® may be reproduced for educational, noncommercial uses only. Copyright © 1997 Search Institute ® , 615 First Avenue NE, Suite 125, Minneapolis, MN 55413; 800-888-7828; www.search-institute.org. All rights reserved.

5

Hartland Optimist Club Adopt a Family Food Drive

Annual Shop with a Cop Christmas Event

8

Jonathan Buckley volunteering at the Arc of Livingston Fundraiser

9

Annual Bell Ringing for The Salvation Army

SUPPORT 1. Family support: Family life provides high levels of love and support. 2. Positive family communication: Young person and her or his parent(s) communicate positively, and young person is willing to seek advice and counsel from parent(s). 3. Other adult relationships: Young person receives support from three or more nonparent adults. 4. Caring neighborhood: Young person experiences caring neighbors. 5. Caring school climate: School provides a caring, encouraging environment. 6. Parent involvement in school: Parent(s) are actively involved in helping young person succeed in school.

EMPOWERMENT 7. Community values youth: Young person perceives that adults in the community value youth. 8. Youth as resources: Young people are given useful roles in the community. 9. Service to others: Young person serves in the community one hour or more per week. 10. Safety: Young person feels safe at home, at school, and in the neighborhood.

BOUNDARIES & EXPECTATIONS 11. Family boundaries: Family has clear rules and consequences and monitors the young person’s whereabouts. 12. School boundaries: School provides clear rules and consequences. 13. Neighborhood boundaries: Neighbors take responsibility for monitoring young people’s behavior. 14. Adult role models: Parent(s) and other adults model positive, responsible behavior. 15. Positive peer influence: Young person’s best friends model responsible behavior. 16. High expectations: Both parent(s) and teachers encourage the young person to do well.

CONSTRUCTIVE USE OF TIME 17. Creative activities: Young person spends three or more hours per week in lessons or practice in music, theater, or other arts. 18. Youth programs: Young person spends three or more hours per week in sports, clubs, or organizations at school and/or in the community. 19. Religious community: Young person spends one or more hours per week in activities in a religious institution. 20. Time at home: Young person is out with friends “with nothing special to do” two or fewer nights per week.

18

COMMITMENT TO LEARNING 21. Achievement motivation: Young person is motivated to do well in school. 22. School engagement: Young person is actively engaged in learning. 23. Homework: Young person reports doing at least one hour of homework every school day. 24. Bonding to school: Young person cares about her or his school. 25. Reading for pleasure: Young person reads for pleasure three or more hours per week.

POSITIVE VALUES 26. Caring: Young person places high value on helping other people. 27. Equality and social justice: Young person places high value on promoting equality and reducing hunger and poverty. 28. Integrity: Young person acts on convictions and stands up for her or his beliefs. 29. Honesty: Young person “tells the truth even when it is not easy.” 30. Responsibility: Young person accepts and takes personal responsibility. 31. Restraint: Young person believes it is important not to be sexually active or to use alcohol or other drugs.

SOCIAL COMPETENCIES 32. Planning and decision making: Young person knows how to plan ahead and make choices. 33. Interpersonal competence: Young person has empathy, sensitivity, and friendship skills. 34. Cultural competence: Young person has knowledge of and comfort with people of different cultural/racial/ethnic backgrounds. 35. Resistance skills: Young person can resist negative peer pressure and dangerous situations. 36. Peaceful conflict resolution: Young person seeks to resolve conflict nonviolently.

POSITIVE IDENTITY 37. Personal power: Young person feels he or she has control over “things that happen to me.” 38. Self-esteem: Young person reports having a high self-esteem. 39. Sense of purpose: Young person reports that “my life has a purpose.” 40. Positive view of personal future: Young person is optimistic about her or his personal future.

Brighton Girl Scout Troop creates backpacks for foster children

27 37

4H Rangers Matching Money Monday Bake Sale Fundraiser

36

Brighton and Hartland High School Unified Basketball Game

Pinckney High School Mentors in Violence Prevention