5 minute read

Ākonga become scientists to clear the air on pollution

Hands-on science kits are helping primary students across Aotearoa contribute to real scientific research while sparking a love for maths, critical thinking and discovery.

“When it comes to maths, you have to start with concrete materials and eventually build towards abstract thinking,” says Whareama School teacher Dianne Christensen.

Dianne believes making learning ‘real’ is essential to getting ākonga enthusiastic about maths and science.

This year, Dianne is using science kits to teach students about respiratory health and air pollution. The kits include two air monitors that collected data on her classroom’s air quality.

Ākonga ran tests with these monitors and recorded their output, sending this data to scientists for use in air quality research.

“The kits are so well set up for teachers who lack confidence in science,” says Dianne. “You get the full lesson plan and all the equipment; everything’s ready to go.”

Real-world contexts

“Connecting [maths and science] to real-world contexts is a powerful way to engage kids,” says Dianne. “And honestly, it keeps me engaged too. I want to be learning, trying new things, finding ways to stay engaged alongside the children.”

Beyond their use in the classroom, these kits are also helping scientists like Dr Ian Longley collect valuable data.

Before Covid, few New Zealanders thought about air pollution. Contaminants from cars, industry and households felt like problems for larger, busier countries. Ian says this is a common misconception.

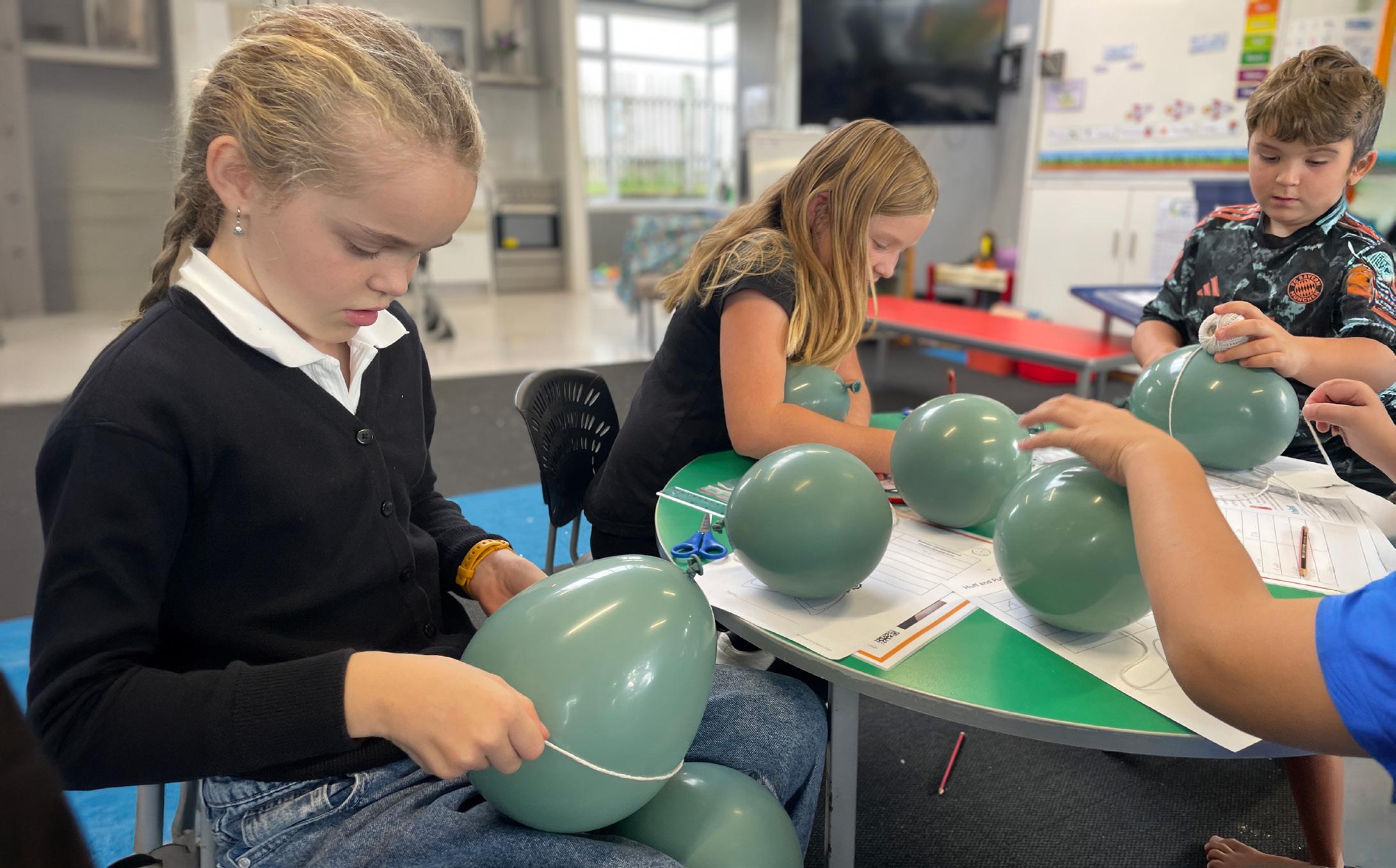

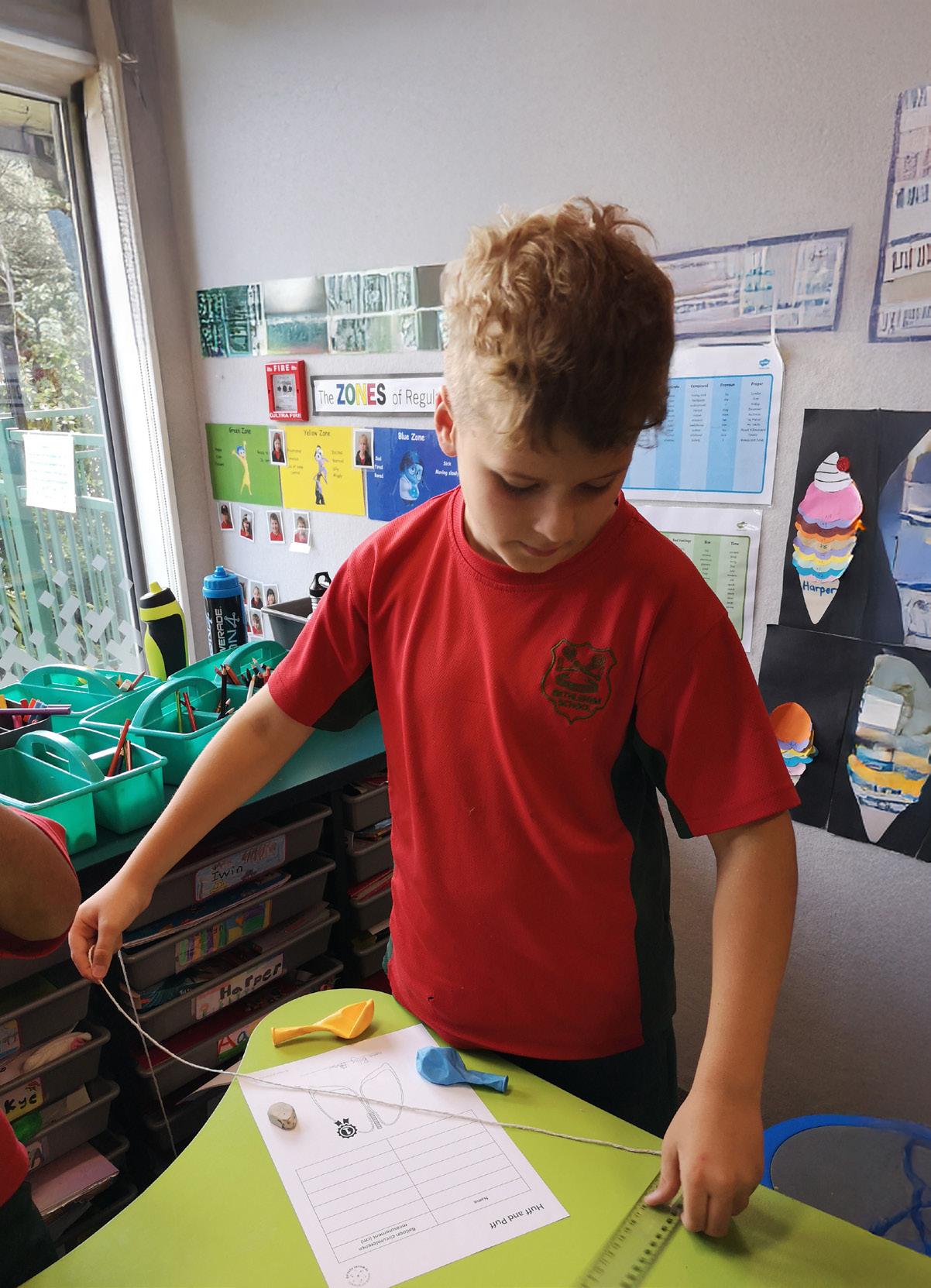

Measuring balloon circumference is one of the activities helping ākonga learn about lung capacity and respiratory health.

“New Zealand has fantastic air quality, most of the time, in most places,” admits Ian. “But not everywhere, and not all of the time.”

After NIWA disbanded its air quality unit in 2024, Ian co-founded the Clean Air Collective to better understand and confront the country’s air quality challenges. His work involves empowering communities to acknowledge threats to respiratory health and the ways individuals affect air quality.

“For students and teachers, bad air affects staffing, learning outcomes and school operations,” says Ian, highlighting asthma alongside the spread of mould and viruses as the main issues tied to air pollution.

Sparse data presented a massive hurdle for Ian’s research. Regional councils have monitored air quality since 2005, but most towns use bulky, expensive equipment, resulting in roughly one monitor per district. Ian knew Aotearoa needed more information around indoor air quality, especially after the pandemic.

Inspiring young researchers

“Suddenly [after Covid], people were much more attuned to indoor air quality,” says Ian.

“But we didn’t have the data. No one was routinely monitoring indoor air in schools … Then the final piece of the puzzle came into place. Working with schools is a great way to start those conversations.”

Ian explains that ākonga take the issues seriously and they take the conversation home.

“They don’t own cars or houses. So, they see things more clearly. They think, ‘Of course the environment should be clean.’

“[The kits] opened the door to mass participation in air quality monitoring and helped build a much more comprehensive picture of what New Zealand’s air is really like.”

Emergent learning in action

For Dianne’s class, the kits covered more than just pollution and data collection.

“We explore breathing as a process, pollution, what air pollution is, how we measure it, and why it’s important,” explains Dianne. “And we tie that into maths.”

For example, investigating lung capacity naturally led to lessons in geometry.

“We did repeated measurements of balloon circumference, used those to calculate diameter, and then compared everyone’s results,” says Dianne. “That led to a discovery of pi, not as a formal topic, but they saw a pattern.

“It was a great moment of emergent learning,” she continues. “It was more about seeing patterns than naming constants. That’s where the learning stuck.”

This pattern of emergent learning continued throughout the module. Ākonga investigated dust mites; mapping out one square metre on the classroom floor and estimating how many mites would be in it (answer: about 100,000 mites. Students were disgusted).

“Even if they don’t remember every fact, they remember the experience,” says Dianne.

Students as scientists

“I really like these lessons,” says Isaac, one of Dianne’s Year 8 students. “Just seeing how things change.”

Isaac particularly enjoyed using the air monitors. Their output, and his first-hand experiences with real scientific methods and data, meant that lessons surprised him and led to knowledge that stuck.

“I didn’t know microparticles could get into our bloodstream just from breathing. I thought our lungs only took in oxygen,” he says. “It was fun.”

For Dianne, whom Fulbright selected in 2018 for their Distinguished Awards in Teaching programme, blending disciplines is an effective way to electrify subjects that might otherwise elicit groans from sections of her class.

Measurement

“This is just how I teach,” she says. “Sometimes [ākonga] will ask, ‘Are we doing science again?’ And I’ll say, ‘No, we’re writing; we’re just doing it through science.’”

Looking to the future

Looking ahead, Ian sees science kits as a win for teachers, students and scientists. He’s happy to see ākonga contributing to real, hands-on research.

“Hopefully, this opens the door for a different kind of relationship,” he says. “One where kids are researchers, teachers are facilitators, and the data has real value.”

Science and pūtaiao kits for Years 0-8

In Budget 2025, $39.9 million in operating funding was set for science and pūtaiao kits. A library of hands-on kits will be made available to all schools and kura with learners from Years 0 – 8, to improve science education outcomes.

The kits will empower teachers to deliver the new knowledge-rich science and pūtaiao curricula and will be accompanied by teacher development opportunities to make science more engaging and accessible for students.