13 minute read

Equestrian in the NCAA

The NCAA is the collegiate athletic governing body. According to the Encyclopedia Britannica, it is officially defined as the “organization in the United States that administers intercollegiate athletics.” The association manages players, coaches, teams, and scholarships throughout colleges nationwide. The NCAA is most popularly known due to college football games and March Madness, the NCAA Division 1 basketball tournament. March Madness generates national bets and attention towards the association, but the NCAA is not just for basketball. It features dozens of less known men’s and women’s sports. The sports range from gymnastics to rowing to lacrosse and more, but I’m most focused on a more recent addition to the NCAA’s emerging sports program: Equestrian. Yes, a controversial one. Many people believe that horseback riding is not a sport, however the NCAA has officially labeled it an emerging Women’s college sport since 1998. This means that the sport is smaller but still fully sanctioned with the association. As of now, only Division 1 and Division 2 teams can officially exist under NCAA sanction for equestrian competition. The recruitment process for an equestrian athlete is pretty much the same as that of any other NCAA Athletes. You need to complete recruitment questionnaires, attend college fairs, tour schools, and meet teams in the same way as each other sport within the association. Additionally, you must be approved through the NCAA by sending your transcript, SAT scores, and resume. Schools can offer scholarship money for riders to become members of their teams, but since the sport is smaller, it is less common. NCAA Equestrian teams also have strict GPA Regulations and grade standards. They practice regularly and work out as a team outside of their practices. There’s been a recent shift in traditional horseback riding competitions towards being about money, like many other aspects of the equine industry. Rather than competing on level ground, it becomes a popularity contest for who has the most expensive horses, equipment, trainers, or is friends with the judge. The intercollegiate format of equestrian competition is much more equalized and is based on skill, which is commendable. Rather than competing on your own horse, college athletes are assigned the name of a random horse(s) and then asked to complete the competition on it. This subtracts the money factor and showcases a rider’s ability to adapt to an animal on short notice. According to the governing board, the National Collegiate Equestrian Association (NCEA), riders are judged on factors such as, “consistency on course, smoothness, flow from jump to jump,” “accuracy and overall position of the rider,” “seat of the rider and the correctness and effectiveness of her aids,” and “ability to ex-

Senior Anna Langan competes in an equestrian competition. Photo supplied by Anna Langan ‘22 Langan will continue her career in college as an NCAA D1 or club athlete. Photo supplied by Anna Langan ‘22 ecute a prescribed set of maneuvers with precision.” This creates a highly competitive atmosphere within the sport, but the level of skill riders cultivate lasts a lifetime. The NCEA prides itself on “providing collegiate opportunities for female equestrian student-athletes to compete at the highest level, while embracing equity, diversity and promoting academic and competitive excellence,” and they are working towards achieving this!

Advertisement

Nog Off: a surprising charitable tradition

By TIANA CYRELSON ‘22 Media Editor

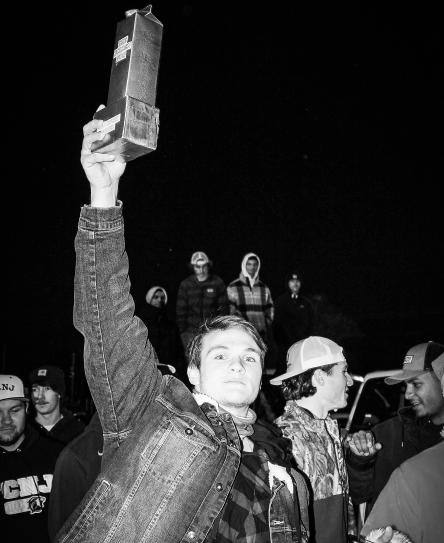

In November of 2018, a few upperclassmen gathered in the parking lot of the Walmart, shivering as they each held a half-gallon carton of eggnog in their hands. There was only a small group of them, maybe six or seven—but the videos they posted on their Snapchat stories that night would be viewed by over a hundred people. One of them counted down from three, and on the signal, they each raised their carton to their lips and began to chug. The goal was to be the first to finish the half-gallon of thick liquid and be crowned the Nog-Off champion. “I wasn’t there,” said Owen Donahue, the current head of Nog-Off. “I don’t remember if I knew what it was at the time it happened. It wasn’t my idea.” Donahue didn’t join in on this disgusting tradition until the following year, as the event grew in popularity. He recalls posting a flier on his story, encouraging others to come to the event. “Nobody really ran it,” said Donahue. “We just did it because it was funny,” he said. “It started as a joke.” In November of 2019, over 20 teens showed up in the parking lot. They drank nog, some threw up, and one was crowned Nog-Off champion. “It’s terrible,” Donahue says. “Friend to friend? Don’t do it. It ruins your entire night. It changes your perception of eggnog. Definitely.” As the 2020 Nog-Off season approached, Donahue recalls thinking about what he could do with the growing support for the event. He posted an announcement on his Snapchat stating, “Nog-Off is now a charity event,” along with the link to his Venmo for contributions towards Toys for Tots. “I thought I’d get like 200 bucks,” he says, “but going into Nog-Off, we were already at $1,600.” The incredible support for the event was astounding and caught Donahue off guard. “It was so out of left field,” he described. The day of the event came with over 90 participants, $2,200 raised, and over 300 toys purchased. Owen and his friends were able to purchase over three hundred toys. Donahue recalls this moment as an important one, marking his realization of the difference he could make in the lives of underprivileged children. Then, as the 2021 Nog-Off season began to approach, Donahue remembers feeling the pressure of the upcoming event. Busy with work, school, and sports, it was difficult to plan the event. However, Donahue decided to reach out to the Berlin Farmers Market. “Last two years, the cops ended up coming after it was over. This year, if the cops came, I wanted to have backup,” he said. Much to Donahue’s surprise, the Berlin Farmers Market approved his request. With the go-ahead from the market, Donahue knew he had to go through with it. “It’s really not a well-run event,” he says. “I don’t want it to be. I don’t ever want people to feel like they have to donate or they have to give money to go to Nog-Off. If you have money to donate, please do. If not, just come to Nog-Off.” Donahue understands that not all participants are able to donate, but he appreciates their support of the event nonetheless. Nog-Off stands as an event for entertainment above all else. While he has tied in a charitable contribution, he focuses his efforts on maintaining the integrity of the lighthearted event. Two weeks later, on the night of November 27th, 2021, over 120 people gathered in the parking lot of the Berlin Farmers Market, many holding their own cartons of Eggnog. Owen Donahue, donning his Santa Suit and stepping up to the line of contestants, waited for the count down. The guys began to chug, and John Sacco, a friend of Donahue’s, was crowned the Nog-Off 2021 champion. Although the night of festivities was over, the work was just beginning for Donahue and his friends. The boys collected over $3,000 to spend on toys and began their shopping. “My favorite memories are buying the toys,” Donahue says, “the feeling of being a kid again and buying thousands of dollars of toys with your friends and knowing that they’re going to kids who don’t have them.” Using Sacco’s employee discount at the local Target, Donahue and his friends were able to buy even more toys. They focused on getting a wide array, from toddler toys to tween entertainment, for boys and girls alike. On December 6th, the first delivery of toys was made to a local school district, and the rest will follow shortly. Despite his humility about his success, Donahue has created an important event he hopes will last years into the future. As long as people continue to show up, he hopes to continue to host these events. “Until people stop showing up, I feel it’s my obligation almost to keep doing it,” said the host. While he does not make a penny from the events, Donahue enjoys furthering the spirit of Nog-Off. “Without other people, Nog-Off is nothing—so I guess everyone coming together and contributing to Toys for Tots is what it’s all about,” he said. The event started as a joke, but it has turned into a charitable tradition far greater than expected. In the spirit of Christmas, people continue to gather on the cold November nights, embracing the true meaning of the holiday: drinking eggnog past the point of sickness. Nog-Off now stands as an opportunity for teens to get together, celebrate the holiday season, and support a noble cause: a future Owen Donahue never would have predicted, but is more than happy to continue.

John Sacco, this year’s Nog-Off champion, raises the Nog-Off trophy. Photo by Wesley Andrews

In 2021, any teenager might stroll into the crowded halls of their middle or high school, join their group of friends perched against the metal lockers and greet them with, “What’s good, fam?” They’ll trade laughs and talk in loud voices, with sentences like “I’m finna go off this weekend” and “Stop capping” flying around. A teacher might walk by and mutter under his or her breath, “these kids and their slang.” Words and phrases like “on fleek,” “periodt,” and “snatched,” to name a few, are in the daily vernacular of GenZ. They smile at their phones, thumbs twiddling away, texting words such as “purr” and “bae” because they’re trending in the TikTok comment sections. However, some Gen-Z members don’t know that these words are buried into history and already have a name, entitled African-American Vernacular English (AAVE) or Ebonics. AAVE has a controversial origin. Some critics suggest that it originated after African slaves arrived in America, in their attempts to learn their captors’ language. Other critics suggest that AAVE was already a language: a mix of Creole and various West African languages. In 1996, it became known in the Black community as Ebonics, which is a portmanteau of the words ebony (black) and phonics (sounds). At the time, the Oakland Unified School District tried to use AAVE as a way to help Black children understand standard American English, and attempted to declare it as its own language. This only caused a spark of outrage, as people questioned things like “ain’t ‘ain’t’ a word?” How is AAVE grammatically written? There are many rules of AAVE; to name a few, compared to standard American English, AAVE excludes to-be verbs like “is” and “are.” For example, “he be workin’’’ or “I know you playin.” AAVE also uses negative concords (double negatives), which is a huge grammar red flag in standard American English. If an English teacher heard you say, “Can’t nobody say he ain’t workin,” they’d correct you, but this is acceptable in AAVE. What’s the problem with AAVE in society? The short answer is racism and linguistic stigma. Many of the things Black people do are defective in America, so it’s no surprise that the way they speak is one of them.

To grammar police and other linguists of the world, AAVE is “broken English” or “lazy speaking,” and those who use it are considered uneducated and unsophisticated. AAVE reaches a massively-wide audience when rappers such as Drake, Jay-Z, and Kendrick Lamar use it. Hip-hop and rap artists commonly use AAVE, sometimes even creating new words. Because of this exposure of culture, it’s okay to rap in AAVE, but not speak it in a professional setting or around people who don’t speak it. This opens up a new can of worms, inviting breathy slurs like “ghetto talk.” Because of this, some Black people will code-switch (when Black people switch the way they’re speaking and acting to interact with those around them, usually colleagues). Personally, I’ve been told that I speak “eloquently” or “White” when I’m not using AAVE. I’ve also heard people say things like “I’m using a Blaccent” when they’re not Black themselves, as if to mock the way some Black people speak. At the end of the day, members of Gen-Z Gen-Z’s internet slang has a deeper history than should understand that phrases like “chile what’s in TikTok’s comment sections. anyway,” “sis,” and “real one” aren’t inPhoto by Mahawa Bangoura/Canva ternet slang, nor are they solely part of vernacular. They have a history that we are partaking in. So, please be aware that it’s nothing new, before “the OG’s put you on blast.”

The Class of 2023: How stressed are juniors?

By LAN ANH NGUYEN ‘23 Staff Reporter

Junior year is infamously known as the hardest year of high school. Juniors are piling on AP classes to challenge themselves as well as to look good for colleges. On top of the harder classes, they have to worry about SATs, AP exams, and driver’s tests. In addition to all this madness, they also have to start researching and visiting colleges, and make time for their friends and family. It is definitely a vigorous year for sixteen to seventeen-year-olds. However, this year is even harder on the Class of 2023 due to COVID-19. Last year, students didn’t have to worry about getting dressed or traveling to school. Classes at Eastern started at 8:00 AM last year; now the first period begins at 7:30 AM, which means most students have to wake up at 6:00 AM. School was also on Zoom, which means it was easy for students to nod off and not pay attention, which is why AP scores were lower last year. These learning difficulties also affected this year, because sophomore year, like any other year, was the foundation for the next year, especially in terms of tough classes like US History II and Precalculus. This year, class time was extended back to pre-COVID timing, which means students need to have longer attention spans; not to mention a change in the learning environment. Back in quarantine, you were by yourself with family; this meant less gossip, judgment, toxicity, and more of a healthy lifestyle. Now, people have to worry about what they wear, and how to act. So after so much added responsibilities and such a massive adjustment, how are juniors doing? As a junior myself, I can definitely say the change was not easy. During September and October, I was struggling with time management because I wasn’t used to getting so much work. I would push everything off and sometimes turn work in late or not even do it at all. It was obvious that I lacked work ethic. Then, when my grades dropped and the lectures from my parents arrived, I knew I had to pick up the pace. I interviewed over twenty juniors, and most of them shared similar problems. “Time management is key for a successful high school career,” said Mahek Jhaveri, who is balancing four AP classes. On top of that, juniors also mentioned how they were not getting enough sleep due to all the work. Some students were skipping meals, such as lunch in school, because of labs or to complete the work they didn’t finish the night before. “I can’t eat when I’m stressed,” Siya Nayyar said. Other students just plainly forgot. For students who play sports, it’s a strong commitment of likely six days a week and two hours per day. By the time they get home, it’s pitch-dark, and their bodies and minds are so exhausted that it’s hard to study or finish any work. As juniors, a lot of us are achieving leadership positions in clubs, which means more commitment and time. Therefore, time with family and friends has decreased. Obviously, not all juniors are struggling. Some people were able to transition with ease. They were able to get their work done in school or immediately after school, so that they would have the whole evening to do other things. Now that it is December, most juniors are used to the schedule and their classes, but they also feel very burned out. Winter break can’t come soon enough!

All the responsibilities that come with being a

junior — SATs, AP exams, college searching, many 11th graders find themselves stressed. Photo by Lan Anh Nguyen/Canva