7 minute read

WILD VOICES

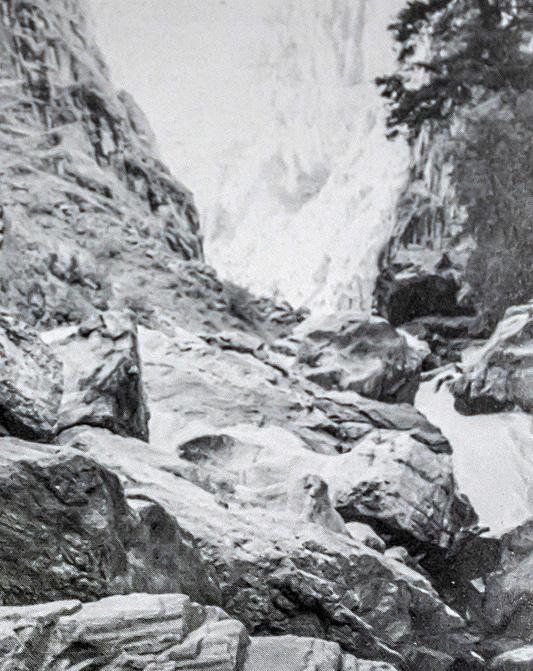

Vandenbusche and John Hrovat portage their crew’s 33-pound Caravel boat during their 1972 expedition down the Black Canyon of the Gunnison River. photo courtesy of Duane Vandenbusche

Dr. Duane Vandenbusche

Advertisement

Gunnison Valley virtuoso Dr. Duane Vandenbusche is the first-ever Western Slope chronicler to be named Colorado State Historian in the position’s 96-year history

BY MORGAN TILTON

Duane Vandenbusche stood on the gravel bar, blanketed with splintered debris and rocks, peering down the Narrows, one of the most dangerous sections of The Black Canyon of the Gunnison River in Colorado. Vandenbusche, then 35 years old, leaned against the jutting corner of the cliff, completely alert and trying to decode the obstacles downriver. T he canyon bottlenecked to 44 feet wide with no shore, and its vertical walls towered more than 2,000 feet above the expeditionists’ sopping wet boots. Vandenbusche and his two friends, David Nix and John Hrovat, could not see beyond the upcoming bend. But a foamy current was in sight, a sign of Whirlpool Rapid, which immediately followed this tight artery.

It was 1972. The base of the dark rock was lightertoned, near the water’s surface, where the levels surged from winter runoff — yet another sign of the wild and unpredictable environment. They were more than halfway through their four-day, 53-mile venture through the canyon, from the old railroad town of Sapinero to the town of Lazear, and completely immersed. The canyon walls ranged from 500 to 2,700 feet high. They wanted to find out if they could thread the entire length of the Black Canyon. “A 25-foot waterfall drop waits for you at the end of The Narrows, if you don’t get out. You have to brush the left wall and exit the water on the left side before reaching the waterfall. It’s a great adventure,” Vandenbusche said. Prior to Vandenbusche’s expedition, the first known footsteps at the bottom of the gorge were of the Tabeguache, a nomadic band of the Ute people, who lived in the region and feared the dark canyon’s raging rapids.

“The canyon was called ‘Black,’ because of its depth, its dark and vertical walls, and because in sections of the gorge, the sun shines only 33 minutes a day. Some canyons of the American West are longer and some are deeper, but none combines the depth, narrowness, darkness and dread of the Black Canyon,” Vandenbusche later recorded in “The Black Canyon of the Gunnison,” one of 11 books the 83-year-old has published on western Colorado.

Few others had ever attempted to discover the perilous Black. In 1900, a five-man crew called the Pelton Party optimistically pushed off from Cimarron to explore the river in its entirety. Their wooden boats, each 300 pounds, had proven unfit for the turbulent rapids and endless portages above shallow stretches, violent zones and over pyramids of humongous boulders.

After 21 days and 14 miles, the party climbed out of the canyon, defeated. Noting their missteps, William Torrence and engineer Abraham Fellows entered the canyon on foot, where they swam and scrambled for 10 days with an inflatable rubber air mattress in tow the following year. They had been commissioned by the U.S. Geological Survey to locate a site for the Gunnison Tunnel, which would transport Gunnison River water to save the Uncompahgre Valley. They succeeded.

Dr. Duane Vandenbusche, a professor at Western Colorado University in Gunnison, Colorado, recently made history as the first-ever Western Slope chronicler to be named Colorado State Historian in the position’s 96-year history. photo courtesy of Western Colorado University

In 1974, Vandenbusche co-rowed former Governor of Colorado Richard Lamm on a 15-mile, two-day whitewater raft trip down the Black Canyon of the Gunnison River. Here, the crew charges through Leapfrog, a quarter-mile set of rapids between Cimarron and East Portal. photo courtesy of Duane Vandenbusche danger. Falling rocks are a danger. Slipping on the rocks 300 feet above the canyon floor, where you sometimes had to walk, would be a danger. Every moment in the canyon, you’re very cognizant,” Vandenbusche said. He had never been to the Mountain West and sagebrush country prior to accepting his professorship at Western Colorado University and road tripping over Monarch Pass, an exposed high-altitude drive that terrified him. “People didn’t move around very much at that time,” he said. “I needed a job and didn’t have a lot of money, so I didn’t think twice about it. It turned out to be the greatest move of my life.” Now, Vandenbusche is in his 59th year of teaching at Western Colorado University. He’s the longest-serving professor in the state’s history. In 1971, he also took over the track and cross country programs and developed the women’s program, serving as the coach for 37 years. His men’s and women’s teams have won 12 national championships. And last August, he was nominated as the Colorado State Historian, a position he’ll serve until Colorado Day 2021. Vandenbusche’s outdoor adventures go hand in hand with documenting and sharing the stories of the Gunnison Valley, too. Every year, he would traverse from Crested Butte to Aspen on Fischer cross-country skis with three-pin bindings (those 50-year-old sticks are still his favorite pair to date). They used pine tar, rather than skins, to climb over 11,900-foot East Maroon Pass. Today, he connects with open space by mountain biking, fishing in the high alpine lakes, downhilling in fresh powder and Nordic skiing the groomed trails. He hikes to Aspen every summer through the wildflowers and backcountry skis Red Lady Basin. There are not many places in this region he hasn’t explored. “The Gunnison country has done a lot more for me than I could ever have done for it,” Vandenbusche said. The preservation of our environment and landscape is innately intertwined to the preservation of history, as well as our experiences in the wilderness that keep us young. “I hope that the Gunnison Valley and Colorado stay pristine and environmentally sound with the protection of our water, resources and the great outdoors,” Vandenbusche said. “I want Colorado to stay eternally young with a lot of freedom and good stewards of the mountains and the

But as far as Vandenbusche knew upon entry, no crew had completed a land. The young are the hope.” full traverse along the Black, although he recently learned that a duo completed the first descent in 1934. MORGAN TILTON is an adventure journalist specializing in outdoor industry news

“I’d gone down many parts of the canyon on fishing expeditions, which and adventure travel. She grew up on Colorado’s Western Slope, where she commenced were tremendous. The fishing was unbelievable,” Vandenbusche said. “And, board sports on snow at her home mountain of Telluride Ski Resort 18 years ago inspiring I’d been reading about Fellows and Torrence, and Fellows gave me his her curiosity to eventually carve waves. Crested Butte, Colorado, is home.materials and notes. He’s a big hero of mine. I wanted to go all the way — because, no one really knew too much about going all the way.”

The pioneers pulled along a 75-pound Avon Redshank raft, which was “way too big,” he said.

“You can’t run a lot of that water in the canyon,” Vandenbusche said. “There are too many rocks, too many waterfalls, you can’t really see where you’re going (with the canyon bends) and the water drops very fast.”

They brought 100 feet of silk rope, life preservers and iodine tablets. They slept on ponchos in the sand, shivering through the cold nights, and ate canned food — with the exception of fire-roasted steak on night one. Heroically, they made it through The Narrows and to their take-out at Pleasure Park. They celebrated, but wanted to improve their time; so they returned the following year with a slimmer, 33-pound Caravel. They, again, finished in four days. Vandenbusche (left) stands with Dick Eflin — who co-opened the

“Looking back, it was probably more risky than we thought at the time. If Crested Butte ski area in 1961 — and Bill Allen (right) at the top of Eflin’s Way ski run. photo courtesy of Duane Vandenbusche you got hurt in the canyon, it’s very difficult to get out. The water is a