9 minute read

ROAMIN' OLD ROADS

Roamin’ Old Roads with Hoffman Birney

A novel inspires a modern-day road trip across the American West

BY MORGAN SJOGREN

In 1928, author Hoffman Birney haphazardly threw a bedroll, thermos, shovel and revolver into his Chrysler Roadster, that he affectionately referred to as Betsy, and set off on what may be the first documented iteration of the iconic “great American road trip.”

According to Southwest historian Gary Topping, “his purpose, at least in part, was to demonstrate the degree to which the automobile could serve as a practical transportation through in the hitherto undeveloped West.”

Starting from his home in Tucson, Arizona, Birney drove a 7,250-mile loop around the western U.S. covering the

Grand Canyon, Four Corners, Rocky Mountains, Mojave

Desert, Yosemite/Eastern Sierra, Idaho, Montana and the

Navajo Nation.

Though Birney was a prolific Western author, he originally compiled his tales from the road for his friends, with no intention of publication. His easygoing tone makes the reader feel as if they are in the passenger seat as he assures, “I made no more preparation for the trip than I would to drive to town.” The resulting travelogue, "Roads To Roam," became one of Birney’s most beloved of the eleven Western novels he penned, influencing

Western tourism.

Admittedly, I have a bit of a historical crush on Birney, who appears timelessly cool in short shorts, a brimmed hat, aviator shades and rippling ab muscles in lieu of a shirt.

However, while Birney looks as if he could seamlessly step into 2021, the landscapes, highways and towns he wrote about do not. His musings in "Roads To Roam" spotlight

Four Corners destinations that continue to be iconic road trip destinations today. Furthermore, Birney reveals just how much of this region has been altered and infiltrated by human development in the last century, much of it originating during the years immediately preceding and following Birney’s big trip.

Today, driving around the Southwest with a copy of "Roads To Roam" feels like bringing Birney himself along for the ride, and his frank descriptions of iconic road trip destinations and routes are still relevant today while helping modern travelers like myself perceive just how much these places have changed. ››

"Roads To Roam" by Hoffman Birney transports readers through the Southwest on a 100-year-old road trip. photo by Morgan Sjogren

A portrait of Hoffman Birney. Photo courtesy of Utah State Historical Society

A view of the Mesa Verde skyline that has given generations of travelers a glimpse back in time. photo by Morgan Sjogren

“Here lies the true painted desert … the use of the term to describe any other terrain in the southwest is not justified.”-Hoffman Birney photo by Morgan Sjogren

FLAGSTAFF, AZ

As I roll into Flagstaff, I am pleased to note that the attractions that caught Birney’s attention are still prominent today. Known as a tourism hub since the early 1900s, the newly minted Route 66 first paved its way through Flagstaff in 1926, opening passage for road warriors like Birney who would have taken the route past Humphreys Peak towards his next destination, the Grand Canyon. “There is a toll road kept in excellent condition, that works up through the pines to well above timber line on the San Francisco Peaks that tower over town.”

While the population was a meager 3,000 in 1928 (the year it was first incorporated) compared to the robust 75,000 today, Flagstaff still boasted a fusion of touristy stores and nearby wilderness. “Within what one might call the metropolitan area of Flagstaff are interesting ice caves out back of O’Leary Peak, the prehistoric ruins at Eldon and Wupatki; and sunset mountain Flagstaff is on the old National Trails Highway, and is, along with Williams, the principal port of entry to the Grand Canyon.”

Yes, the Flagstaff of 2021 is much larger; and yet one might still describe it in a similar fashion while standing on the corner of Main Street next to the old train depot today with a cup of gourmet coffee from Firecreek Roasters. This mountain town is still a gateway to desert adventures.

SOUTHEASTERN UTAH/ NAVAJO NATION

From car commercials to Instagram posts, the vast stretches of desert passing through the Navajo Nation and Four Corners are symbiotic with road trip culture. While extreme weather conditions and long stretches between towns with gas stations remain a peril to unprepared travelers, the passage is far less of an adventure than it was for Birney.

“Somewhere in America there may be — I say there may be — three hundred miles of road worse than between Cortez, Colorado and Tuba, Arizona. There may be, but I doubt it; and I know I would not wish to drive it.”

Today, Highway 160 is well-paved, although some still complain about driving its narrow two-lane portions at night. The modern highway system used today, passing from Tuba City to the Four Corners, was modernized beginning in 1956 to make way for coal and uranium mining opportunities.

These road improvements certainly facilitated a new wave of road warriors and tourists traveling through the pastel Chinle badlands near the Little Colorado River to the splendid red sandstone cliffs and towers near Kayenta. Of course, Birney was already aware of its appeal as he passed this way, bumps and all: “Here lies the true painted desert … the use of the term to describe any other terrain in the southwest is not justified.”

However, I can’t help but wonder: would Birney have resisted the notion of an improved road if he understood it would open the doors to industrial development in the area ranging from mining and the Glen Canyon Dam to mass tourism that overwhelms once remote destinations?

MILLION DOLLAR HIGHWAY/ HIGHWAY 550

Where the desert roads did not impress Birney, the mountain byways delighted him. Despite the precipitous turns and drop-offs that still chill the spines of drivers in 2021, Birney praised the Million Dollar Highway. “Back and forth we zigzagged, following a broad, well-graded highway that seemed literally to defy the mountains … At the summit the (altimeter) registered 11,300 feet — as close to heaven as Betsy and I have ever been … The road, save for the stretches that were under construction, was excellent.”

Birney, born in 1891, had the ability to recall the changes in this area over the previous decades. “Before this motor highway was built, six-horse stages used to ply between Silverton and Ouray and the trip was regarded as one of the most scenic and adventurous in the West.”

Birney also commented about the outdated railroad system. “I first saw (Silverton) in 1905, traveling there by train from Durango, riding the narrow-gauge D. & R. G. that puffs along through the deep cañon of the Animas River. Wonder if the locomotives in use today still have huge “spark arrestor” stacks?” I think Birney would be quite surprised that almost 100 years later the railroad still utilizes these coal-fired trains to entertain tourists!

Roamin’ Old Roads with Hoffman Birney

As Birney neared Durango on his trip, he felt the still relevant conflict in the area between scenic beauty and overcrowding. “As it is the river and the railroad are crowded. The automobile road (it’s U.S. Highway No. 550 by the way) climbs the mountains south of Silverton, loops back and forth across rounded summits … to enter the Animas Valley.” Birney stopped for a cup of coffee from the Strater Hotel and continued on down the Highway to Mancos.

MESA VERDE NATIONAL PARK

Birney described Mesa Verde National Park (founded in 1906) as a land of mystery, interest and charm. “The Mesa Verde dominates the Montezuma Valley and Point Lookout dominates the Mesa Verde.” The view from atop the Mesa Verde road remains almost as Birney saw it, with the local community of Mancos retaining its rural agricultural charm and small size. “Beyond lies the fertile farmlands of the Montezuma Valley, crossed by a white ribbon that is the road from Mancos to Cortez.”

Above these modern settlements, Mesa Verde National Park still protects an area of Indigenous cultural density Birney explains that, “scarcely a mile of any of these gorges, nor an acre of plateau between them … does not hold a cliff-dwelling, a storage cyst, a house-site, or some other record of prehistoric Pueblo peoples of the Southwest.” He is referring to the Basketmaker and Ancient Pueblo people who inhabited the region between 600-1300 CE. In fact, he even suggests this homeostasis goes back further. “Few of the tourists who, in thousands, visit the Mesa Verde each season can possibly realize how tremendous a population this irregular tableland supported some ten or fifteen centuries ago.”

While the prosperity of these ancient civilizations impressed Birney, the development created by the tourism industry since his previous visit in 1905 startled him. “There’s a fair-sized hotel … numerous tents and cottages that are rented to tourists, and quite a group of artistic ‘dobe structures — museum, recreation halls, administration building, and so on — that make up Park Headquarters.” It’s an ironic juxtaposition considering the prehistoric population exceeded the “boom” that Birney witnessed.

Still, Birney would be relieved to know that the town of Mancos still barely tops a population of 1,000, and in some ways the small farm town at the foot of the national park still resembles the world Birney passed through a century ago.

BIRNEY’S PROPHECY

Mesa Verde proved to be a pivotal point in Birney’s road trip where he could contemplate the past, present and future:

“Twenty three years before I had stood in almost this precise spot and had seen Spruce Tree House, my first cliff-dwelling. It seemed that centuries, aeons, had elapsed since that day in the fall of 1905. I’d wandered far. I’d lost and I’d gained. I’d known adventure adversity, and some measure of success… but here I was again, and the rectangular black windows of Spruce Tree House still stared across the cañon like dead eyes in an ivory yellow skull, eternally mocking the ephemeral emotions of mankind. Hell, why struggle with philosophies? It’ll all be the same in a hundred years.”

I expected to be shocked by the massive changes Birney’s writing reveals. But what I find most intriguing about "Roads To Roam" is how relatable his descriptions remain. Birney’s century old musings about the changes in the Southwest that he experienced in 1928 foreshadow the place we travel through today.

Flagstaff remains a dazzling portal to adventure, the Painted Desert is gorgeous yet certainly no place to breakdown on a 100-degree day, and the San Juan Mountains are exhilarating albeit crowded during the summer months. However, on a quiet, midweek morning in the sleepy town of Mancos, Mesa Verde looming above, one can still notice the distant hum of a rusty old engine, its tires spinning on the gravel road, and wonder if Hoffman Birney has finally returned for a visit.

MORGAN SJOGREN runs wild with words around the Colorado Plateau. In 2018, she published "Outlandish," a collection of stories and recipes written while living on the road and in the wild out of her Jeep (affectionately named Sunny). You can read more of Sjorgen’s books and stories at www.therunningbum.com.

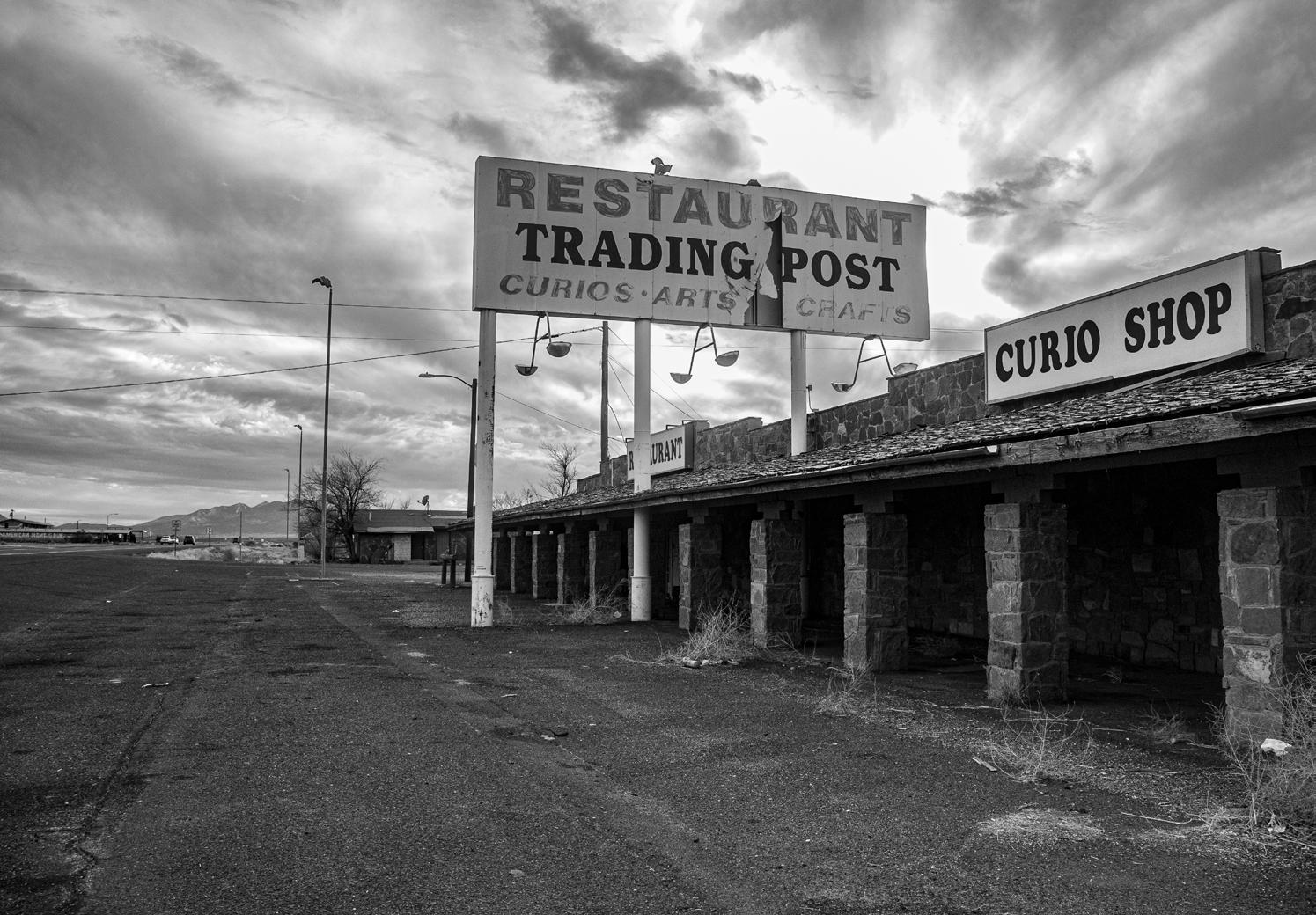

Now abandoned, one can imagine Birney driving past this once lively curio shop one hundred years ago. photo by Morgan Sjogren