17 minute read

Masterworks 4 Program Notes

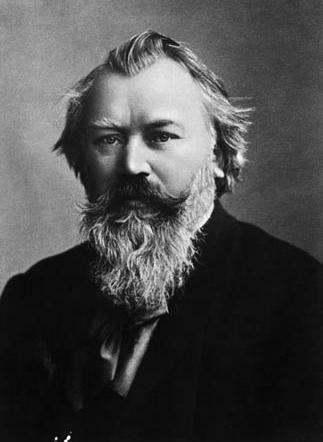

BORN: May 7, 1833, in Hamburg, Germany DIED: April 3, 1897, in Vienna, Austria WORK COMPOSED: 1880 WORLD PREMIERE: January 4, 1881, in Breslau, Brahms conducting PERFORMANCE HISTORY: There have been seven previous DSSO Masterworks Series performances of this work: in 1934, 1947 (the first piece of the three-season tenure of Joseph Wagner, the Orchestra’s third Music Director), 1962, 1967, 1977 (Robert Walton Cole, guest conductor), 1987, and on September 27, 2003. INSTRUMENTATION: Two flutes and piccolo, two oboes, two clarinets, two bassoons and contrabassoon, four horns, three trumpets, three trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion (bass drum, cymbals, triangle) and strings. DURATION: 10 minutes.

Although Johannes Brahms never attended college, at the age of 20 he was introduced to violinist-composer Joseph Joachim who invited Brahms to join him at Göttingen where he would be taking summer courses in philosophy and history at the local university. Brahms hung out with Joachim for two months that summer enjoying reading, debates, beer-drinking sessions and general student camaraderie. As I read this I realized that not much has changed in university life over the past 150-plus years. This reminded me of a band trip when I was stationed with the United States Air Force in Germany in the early 1980s. We went to Groningen in the north of the Netherlands to play at the University of Groningen (founded in 1614!) in the student union. That might sound like a normal performance, except that we didn’t start playing until about 10:00pm and we did three sets, ending around 1:00am! The place was packed with screaming students and beer was flowing generously. After we finished playing I thought that would be the end of the night. Foolish me - I quickly learned that the student union would stay open as long as there were at least two customers still buying drinks. I made it until 4:30 or so before I gave up the night (morning?). I was a little older than Brahms at that time, but I can certainly imagine his life over those two months!

In 1879 Brahms was informed that he was to be given an honorary Doctorate of Philosophy by the University of Breslau (now Wrocław, Poland). This wasn’t the first such honor offered to Brahms; in 1876 Cambridge University offered him an honorary Doctorate of Music, which required his presence at the ceremony. Brahms was paralyzed at the thought of sea travel and then he learned that Londoners were planning lavish celebrations to honor him. Brahms also had a deep fear of public attention. It was too much for him and he chose to relinquish the honor and stayed home. He was flattered by the honor proposed by the University of Breslau and sent a postcard thanking the faculty. However, he couldn’t get away with it a second time; his friend Bernhard Scholz, Director of Music in Breslau, sent him a letter making it clear that the university was expecting gratitude in musical form. During the summer of 1880, while vacationing in Bad Ischl, Brahms composed his musical Danke schön, the Academic Festival Overture.

Instead of a solemn work that might be expected on such an auspicious occasion, Brahms produced what he called “a very boisterous potpourri of student drinking songs a lá Suppé.” (Franz von Suppé (1819-1895) was one of the best known writers of light music of the period, particularly known for his operettas and comic operas.) The result was an enjoyable and delightful spoof on academia and its gravitas. Brahms employed his largest orchestral forces ever and the work sparkles with some of the finest virtues of his orchestral technique.

Harkening back to his adventures in Göttingen, Brahms included some of the drinking songs he may have heard (and probably sang) during his evenings with Joachim and his fellow students. The first song is

JOHANNES BRAHMS

Wir hatten gebauet ein stattliches Haus (We had Built a Stately House), followed by Hochfeierlicher Landesvater (Most Solemn Song to the Founder of the Country). The bassoons are featured in the freshman hazing song, Fuchensritt (Fox-Ride), which English musicologist Sir David Francis Tovey called the “Great Bassoon Joke.” The finale is a full orchestral treatment of Gaudeamus igitur (So Let Us Rejoice), which characterized carefree student life since the late Middle Ages.

Brahms conducted the premiere at Breslau in 1881 at a ceremony full of academic pomp and circumstance. One report has it that the dignity of the occasion was interrupted as students spontaneously burst into song when they heard the familiar songs, most likely adding some of their own irreverent words. Academic Festival Overture remains one of Brahms’ most often performed works. José Silvestre de Los Dolores White y Lafitte (Joseph White) was one of the greatest violinists you’ve never heard of, until now. White was born in Mantanzas, Cuba to Don Carlos White, a French businessman, and an Afro-Cuban mother. His father was an amateur violinist and gave young José his early musical training. On March 21, 1854, White gave his first concert in Mantanzas accompanied by the celebrated pianist, Louis Moreau Gottschalk (1829-1869). Gottschalk encouraged White to pursue training in Paris and raised the money he needed. At the Paris Conservatoire there were sixty applicants vying for a chance to study with Jean-Delphin Alard, the pre-eminent master of the French school of violin playing; White overcame the competition and won the coveted spot. In 1856, he won the Prix de Rome in Violin and two years later began touring Europe, the Caribbean, South America and Mexico. In a letter dated November 28, 1858, Gioacchino Rossini wrote a letter of praise to White: “The warmth of your execution, the feeling, the elegance, the brilliance of the school to which you belong, show qualities in you as an artist of which the French school may be proud.”

White taught at the Paris Conservatoire from 186465 as a temporary replacement for Alard and his first book of Six Etudes for Violin was accepted by the Conservatoire in 1868 as part of its official curriculum. He was awarded the Order of Isabella la Catòlica by the Spanish court in 1863 while he was living in Madrid. In 1870 White became a French citizen and would return to Paris later in life. From 1877 to 1889 he was the director of the Imperial Concservatory in Rio de Janeiro, where he served as court musician for the Emperor Pedro II. White returned to the Paris Conservatoire as professor in 1889 where his most famous pupil was Georges Enescu (1881-1955), who is considered the greatest Romanian musician of all time. Enescu went on to teach the great violinist Yehudi Menuhin (19161999).

In 1876 White performed with the New York Philharmonic and the Theodore Thomas Orchestra (which later became the Chicago Symphony Orchestra); he was the only musician of color to do so at that time. One music critic called him “The best violinist who has visited this country…” During his performing career he held many benefit concerts for various social causes of the day. His concerts were often attended by Cuban expatriates and emigrates who were supportive of the Cuban war for independence from Spain and concert proceeds would often go to support Cuban insurgents fighting in his homeland. White also gave charity concerts for hospitals, children and various churches. One

JOSÉ WHITE

BORN: January 17, 1836, in Mantanzas, Cuba DIED: March 15, 1918, in Paris, France WORK COMPOSED: 1864 WORLD PREMIERE: 1867, in Paris, composer as soloist PERFORMANCE HISTORY: Tonight’s performance of this concerto is the first piece by José White to be played by the DSSO INSTRUMENTATION: Two flutes, two oboes, two clarinets, two bassoons, two horns, two trumpets, timpani and strings. DURATION: 22 minutes.

particular church he had an association with was the Plymouth Church, which during the American Civil War and all throughout the 19th century was an abolitionist center and defender of the rights of people of African descent. White’s purchase of Stradivari’s last violin, the 1737 Swan Song, for $3,000 made the New York Times in an October 10, 1886, issue. Although White is not listed as the purchaser, another source corroborated White as the next owner of the aptly named violin.

White’s Concerto for Violin and Orchestra in F-sharp Minor was composed at the beginning of his touring career. It follows the standard three-movement format of the period: Allegro, Adagio ma non troppo, and Allegro moderato. His choice of key is curious, rare but not an unheard of key for violin concertos. In Mark Clague’s notes for Rachel Barton Pine’s recording he suggests that White may have done it as “a competitive stance” against two contemporary composers who also chose that key in the early 1850s: Heinrich Wilhelm Ernst (1814-1865) and Henryk Wieniawski (18351880). Following in the footsteps of the great Niccolò Paganini (1782-1840), White produced a highly virtuosic work that demands an enormous amount of technical prowess from the soloist. First impressions might leave the listener thinking it is similar to many other concertos of the time, but it certainly is a unique work that utilizes an operatic style in the second movement with recitative and rhythmic passages reminiscent of music from his homeland. In 1867 White performed the premiere of his concerto in Paris. A critic described the work as “one of the best modern works of its kind… The fabric is excellent, the basic thematic ideas are carefully distinguished, the harmonies are elegant and clear, and the orchestration is written by a secure hand, free from error. One feels the presence of a strong and individual nature from the start. Not a single note exists for mere virtuosity, although the performance difficulties are enormous.”

White’s Violin Concerto did not have a premiere in America until 1974, when Ruggiero Ricci performed it in Avery Fisher Hall with the Symphony of the New World. According to a New York Times article from March 3, 1974, it was with the persistent efforts of Paul Glass, who was a professor at Brooklyn College, that he discovered White’s concerto. Glass procured a microfilm of the work from the national library in Paris and approached Ricci and Kermit Moore, who then later conducted its American premiere in a concert featuring music by black composers, honoring Black History Month. As Dr. Glass stated, “there is still considerable work to be done restoring to their rightful stature other works not only by White… but also by the many other black artists who have recently come to light or who are yet to be traced.”

Just imagine all the music we don’t know…

DUKE ELLINGTON

The River EDWARD KENNEDY “DUKE” ELLINGTON

BORN: April 29, 1899, in Washington, District of Columbia DIED: May 24, 1974, in New York City, New York WORK COMPOSED: 1970 (arr. Ron Collier) WORLD PREMIERE: June 25, 1970, at New York State Theater, New York City PERFORMANCE HISTORY: While Duke Ellington’s music has been heard on various DSSO Pops concerts in the late 1990’s and early 2000’s, only one of his pieces has previously been played on the Masterworks Series: Three Black Kings, on October 26, 2002 led by Markand Thakar. INSTRUMENTATION: Two flutes, two oboes (one doubling English horn), two clarinets, two bassoons, four horns, three trumpets, three trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion, harp, piano and strings. DURATION: 20 minutes.

In the history of 20th century American music, Duke Ellington ranks with Aaron Copland, Leonard Bernstein, George Gershwin and other greats. Although he was a pivotal figure in the history of jazz, and in the opinion of Gunther Schuller and Barry Kernfeld, “the most significant composer of the genre,” Ellington embraced the phrase that his music was ‘beyond cat-

egory’ which he considered a liberating principle. He would later classify music into two simple categories: good and bad, and he referred to his own music as ‘American Music.’ President Richard Nixon presented the Presidential Medal of Freedom to Ellington, celebrating his 70th birthday on April 29, 1969, and in 1999 he was awarded a posthumous Pulitzer Prize Special Award for Music.

Ellington’s parents were both pianists. His mother Daisy, daughter of two former slaves, primarily played parlor songs and his father, James, who made blueprints for the United States Navy, preferred operatic arias. The Ellington family showed racial pride and support in their home and similar to many other families at the time, worked to protect their children from the era’s Jim Crow laws. At age seven, Edward began piano lessons with Marietta Clinkscales. His mother surrounded him with dignified women to reinforce his manners and teach him elegance. Ellington discusses in his autobiography, Music is My Mistress (1973), that his childhood friends took notice that his casual, offhand manner and dapper dress gave him the bearing of a young nobleman. He credits his friend Edgar McEntree for the nickname Duke: “I think he felt that in order for me to be eligible for his constant companionship, I should have a title. So he called me Duke.” Although he loved baseball, the tug from music was much stronger. In the summer of 1914, while working as a soda jerk at the Poodle Dog Café, Ellington ‘wrote’ his first composition, Soda Fountain Rag (also known as the Poodle Dog Rag). He could not read or write music at this time and created the work completely by ear. He recalled that he would play it in a variety of styles and the listeners never knew it was always the same piece. By the late 1920s, Duke Ellington was becoming a household name with over a half-dozen hit records. His gig at Harlem’s famed Cotton Club, which was featured on a weekly radio show, brought Ellington and his band national and eventually international attention. By the end of the 1940s, he and his band had over 70 hit records, many being of his own compositions. Jazz historian Gunther Schuller wrote that his “musical vision went way beyond the standard view of jazz.” With Billy Strayhorn, Ellington wrote the film score for Otto Preminger’s Anatomy of a Murder (1959), for which he won three Grammy Awards.

Late in his career Ellington pondered writing a ballet and Lucia Chase, director of the American Ballet Theatre, commissioned him and dancer/choreographer Alvin Ailey to create a work for her company’s thirtieth anniversary in 1970. Ellington showed Ailey his concept of using a river as a metaphor for the passage from birth to death. Because of Ellington’s grueling tour schedule, which he maintained from the 1940s, he completed the score only a month before the premiere. Ailey wasn’t able to choreograph all the scenes in time and Seven Dances from a Work in Progress Entitled The River was premiered on June 25, 1970, at Lincoln Center. Ellington’s friend and collaborator Ron Collier created the orchestral arrangement for that performance. Ailey later added choreography and The River became a staple of the American Ballet Theatre.

The River begins with Spring, described by Ellington as “a newborn baby in his crib . . . wiggling, gurgling, squirming, squealing . . .” Meander blossoms out of a bluesy opening riff, followed by an extended flute solo. The movement meanders into a 12/8 feel, then to a waltz and then returns to the bluesy opening riff and back to the flute solo. Ellington described it as a “baby finding an open door to the outside world.” The baby continues to explore the world and grows through life throughout the remaining movements: Giggling Rapids, Lake, Vortex, Falls, Two Cities, and Riba, until finally ending in a boisterous shout chorus.

Duke Ellington died on May 24, 1974, a few weeks after his 75th birthday. His funeral, at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine, was attended by over 12,000 people. Ella Fitzgerald summed up the somber occasion: “It’s a very sad day. A genius has passed.” Ellington’s gift of melody and his mastery of sonic textures, rhythms, and compositional forms translated his often subtle, often complex perceptions into a body of music unequaled in jazz history.

OTTORINO RESPIGHI

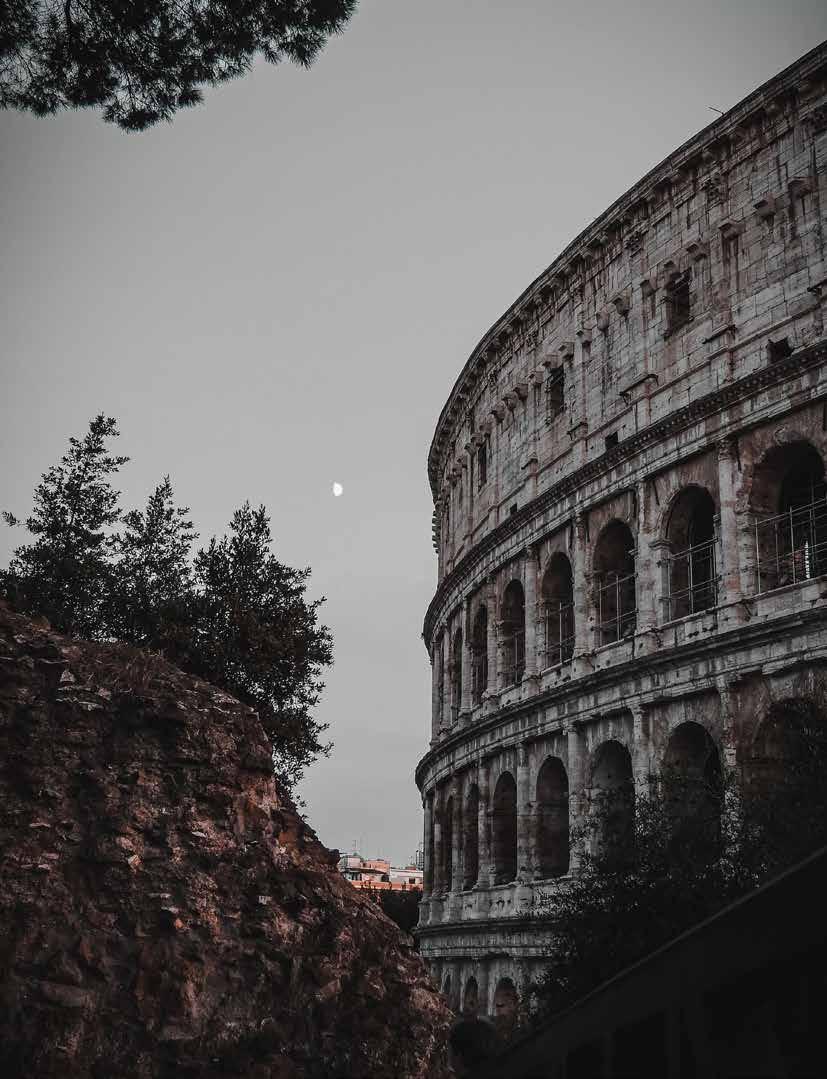

Feste Romane (Roman Festivals) OTTORINO RESPIGHI

BORN: July 9, 1879, in Bologna, Italy DIED: April 18, 1936, in Rome WORK COMPOSED: 1928 WORLD PREMIERE: February 21, 1929, New York Philharmonic, Arturo Toscanini conducting PERFORMANCE HISTORY: The only previous DSSO performance of this work was on January 16, 1982. It was a bitterly cold, windy night. There was an extended intermission so audience members could warm-up their cars, and most returned to the concert. Taavo Virkhaus lead the concert which also included Rachmaninoff’s Second Piano Concerto with Barry Snyder as soloist and Schubert’s Unfinished Symphony, dedicated to the memory of the recently deceased Hermann Herz, the Orchestra’s fourth Music Director. INSTRUMENTATION: Three flutes (3rd doubling piccolo), two oboes and English horn, two clarinets, piccolo clarinet and bass clarinet, two bassoons and contrabassoon, four horns, four trumpets (+three soprano buccine), three trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion (bells, glockenspiel, cymbals, bass drum, field drum, snare drum, ratchet, sleigh bells, tambourine, tam-tam, triangle, wood blocks, xylophone), piano (four hands), organ, mandolin and strings. DURATION: 25 minutes. Respighi celebrated Rome with his popular Roman Tryptich, a set of three programmatic tone poems: Fountains of Rome (1916), Pines of Rome (1924) and Roman Festivals (1928). Roman Festivals is the longest and most demanding of the trilogy, and it is performed less frequently than its companion pieces.

In 1913, Respighi accepted an appointment as professor of composition at Rome’s most famous conservatory, the Saint Cecilia Academy. In 1918, Toscanini planned a series of twelve concerts in Milan for the following year and asked Respighi for one of his compositions to perform. Respighi reluctantly gave him Fountains of Rome, which had received a very lukewarm reception at its premiere in 1917. This time the concert was a huge success and placed Respighi as one of the leading Italian composers of the early 20th century. His second tone poem of the trilogy, Pines of Rome, premiered in Rome in December 1924. It went on to be his most widely known and recorded works. Respighi composed Roman Festivals in nine days at the end of 1928. After its premiere in New York Respighi felt that he had incorporated the “maximum of orchestral sonority and colour” from the orchestra and could no longer write such large scale pieces. He then started to prefer composing for smaller ensembles.

The opening of Roman Festivals takes us to ancient Rome at the Circus Maximus, the largest stadium in its day with an audience capacity of 150,000 (in comparison the largest stadium in the United States is Michigan Stadium in Ann Arbor with a capacity of 107,601; Green Bay Packers’ Lambeau Field holds 81,441 and U.S. Bank Stadium, home of the Minnesota Vikings, seats 66,655)! Imagine the gladiators battling followed by the condemned Christian martyrs chanting as they are pitted against hungry, angry wild beasts. Respighi describes each movement:

• CIRCUS GAMES - A threatening sky hangs over the Massimo Circus, but it is the peoples holiday: “Ave Nero!”. The iron doors are unlocked, the strains of a religious song and the howling of wild beasts float on the air. The crowd rises in agitation: unperturbed, the song of the martyrs develops, conquers and then is lost in the tumult.

• THE JUBILEE - The pilgrims trail along the highway, praying. Finally appears from the summit of Monte Mario, to ardent eyes and gasping souls, the holy city: “Rome! Rome!”. A hymn of praise bursts forth, the churches ring out their reply.

• OCTOBER FESTIVAL - The October festival in the Roman “Castelli” covered with vines: hunting echoes, tinkling of bells, songs of love.

Then in the tender even - fall arises a romantic serenade.

• THE EPIPHANY - The night before Epiphany in the Piazza Navona: a characteristic rhythm of trumpets dominates the frantic clamour: above the swelling noise float, from time to time, rustic motives, saltarello cadenzas, the strains of a barrel-organ of a booth and the call of a barker, the harsh song of the intoxicated and the lively stornello in which is expressed the popular feelings. “Lassàtece passà, semo

Romani!” (“We are Romans, let us pass!”).

Like all great program music, Respighi’s Roman Festivals lets us create the imagery, as if it is the soundtrack to a great movie in our mind.