12 minute read

Masterworks 3 Program Notes

PYOTR ILYICH TCHAIKOVSKY:

Piano Concerto No. 1 in B-flat minor, Op. 23 PYOTR ILYICH TCHAIKOVSKY:

BORN: May 7, 1840, in Kamsko-Votkinsk, Vyatka province, Russia DIED: November 6, 1893, in Saint Petersburg WORK COMPOSED: 1874-75, revisions 1879, 1888 WORLD PREMIERE: October 25, 1875, in Boston, Massachusetts, Harvard Musical Association, Hans von Bülow, piano; Benjamin Johnson Lang conducting PERFORMANCE HISTORY: This evening’s concert is the twelfth featuring this concerto on the DSSO’s Masterworks Series. Soloists for the previous performances were Duluth pianist Miriam Blair (in 1934 and 1944), Jesús Maria Sanromá (1949), Byron Janis (1963), Van Cliburn (on a pair of sold-out nonsubscription concerts in 1970), Andre-Michel Schub (1977, led by DSSO Music Director candidate Andrew Schenck), Natalia Trull (1990), Horacio Gutiérrez (1992), John Browning (on a 1998 all-Tchaikovsky Gala concert), Antonio Pompa-Baldi (2005), and Katherine Chi (September 17, 2011, led by Music Director candidate Rei Hotoda). At the New Year’s Eve Concert in 1988, the first movement was played by Beth Gilbert, the Orchestra’s Principal Keyboardist. In 1942 duopianists Jacques Fray and Mario Braggiotti played an arrangement of excerpts from the first movement with the DSSO.

INSTRUMENTATION: Two flutes, two oboes, two clarinets, two bassoons, four horns, two trumpets, three trombones, timpani, strings and solo piano. DURATION: 32 minutes. It’s hard to believe that one of the world’s most beautiful and recognizable works of music had such a turbulent birth. Such was the case with Tchaikovsky’s Piano Concerto No. 1. In November 1874, Tchaikovsky wrote to his brother Anatoly, “I am now immersed in the composition of a piano concerto. I definitely want [Nikolai] Rubinstein to play it at his concert; it’s going with much difficulty…” At this time, at age 34, Tchaikovsky was a professor at the new Moscow Conservatory while Nikolai Rubinstein was the director of the conservatory from its founding until his death in 1881. He was a younger brother of Tchaikovsky’s teacher Anton Rubinstein, who was then quite well known as a composer. The two brothers thought very highly of Tchaikovsky and Nikolai conducted the premieres of a significant number of his works, which makes even more curious Nikolai’s reaction to hearing the concerto on Christmas Eve of 1874.

Tchaikovsky took the manuscript to Rubinstein to ask about some technical details in the solo part. “I played the first movement,” Tchaikovsky recalled. “Not a word, not an observation! […] Rubinstein was preparing his thunder.” After Tchaikovsky finished, Rubinstein declared that the concerto “was worthless, that it was impossible to play it, that its passages were clumsy, awkward, so awkward that they could not be corrected, that as a composition it was bad, that I stole from here and there, that there are only two or three pages worth preserving […]” This may be the censored version as it elicited Tchaikovsky’s response, “I was not just astounded but outraged by the whole scene. I am no longer a boy trying his hand at composition and I no longer need lessons from anyone, especially when they are offered so harshly and in such a spirit of hostility.” Rubinstein said he would perform it, only if Tchaikovsky would make the alterations he demanded. The composer responded, “I shall not alter a single note; I shall publish the work exactly as it is.” He changed the dedication and asked Hans von Bülow, the distinguished pianist and conductor, if he would accept the dedication and perform the premiere. Von Bülow happily accepted it and, according to the composer’s wish, premiered it as far from Russia as possible - just in case it failed miserably. The premiere was held in Boston with a pick-up orchestra of the Harvard Musical Association (before the founding of the Boston Symphony Orchestra this organization performed regular orchestra concerts). The American audience loved it and demanded an immediate encore of the finale!

The 20-year-old George W. Chadwick, who would become one of America’s leading composers of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, recalled the premiere

performance in his memoirs: “They had not rehearsed much and the trombones got in [sic] wrong in the ‘tutti’ in the middle of the first movement, whereupon Bülow sang out in a perfectly audible voice, ‘The brass may go to hell.’ This was the first Tchaikovsky piece I ever heard and I thought it the greatest ever, but it rather mystified some of our local scribes [the critics], who could not have dreamed how many times they would have to hear it in the future.” Von Bülow declared that the concerto “displays such brilliance, and is such a remarkable achievement among your musical works, that you have without doubt enriched the world of music as never before. There is such unsurpassed originality, such nobility, such strength, and there are so many arresting moments throughout this unique conception; there is such a maturity of form, such style—its design and execution, with such consonant harmonies, that I could weary you by listing all the memorable moments which caused me to thank the author—not to mention the pleasure from performing it all. In a word, this true gem shall earn you the gratitude of all pianists.”

Tchaikovsky did make a few revisions and the version we most frequently hear today was prepared in collaboration with pianist Alexander Siloti (a cousin of Rachmaninoff) during the winter of 1888-89. In a letter to Siloti, the composer wrote that he left the concerto’s “fate to your discretion regarding everything except form [in other words, no cuts and no reordering sections of the piece]. You can edit the piano part as you like, change the markings (but leave my new markings, please), and I will be incredibly grateful to you for proofreading.” Rubinstein came around as well; a few years after the premiere he performed it himself and became a champion of it, which pleased Tchaikovsky very much.

The massive block chords and soaring tunes that open Tchaikovsky’s Piano Concerto No. 1 are famous and deservedly so; their majestic announcement demands attention. From the beginning the orchestra and soloist act in collaboration, with the strings playing the most famous melody accompanied by the piano in arpeggiated block chords. It isn’t until over four minutes into the concerto when the piano takes over as the soloist, but almost always sharing the spotlight with this or that section of the orchestra. The main theme is derived from the Ukrainian folk song Oi, kriache, kriache, ta y chornenkyi voron… that Tchaikovsky heard performed by a blind musician at a market near Kiev (Kyiv).

The second movement opens with the solo flute introducing the main theme, followed by the strings and piano. The prestissimo middle section melody is derived from the French chansonette, Il faut s'amuser, danser et rire (One must have fun, dance and laugh), a staple of soprano Désirée Artôt’s repertoire. Artôt (1835-1907) was a Belgian soprano who was famed in German and Italian opera. In 1868 she was engaged briefly with Tchaikovsky; some say this may have been Tchaikovsky’s first serious attempt to conquer his homosexuality. Although one can almost imagine the two dancing to its cheerful melody, the underlying piano solo adds a touch of discomfort to the joy.

The finale opens with a Ukrainian vesnianka (a type of spring dance song that has been performed for thousands of years in what is now Ukraine) Vyidy, Vyidy, Ivanku (Come to us, Ivanku). The second theme has a motivic bond with the Russian folk song Poydu, poydu, vo TsarGorod (I’m Coming to the Capital).

After Russia was banned from all major sporting competitions from 2021-23 by the World Anti-Doping Agency, individuals cleared to compete were allowed to represent the Russian Olympic Committee or Russian Paralympic Committee at the 2020 Summer Olympics and Paralympics. Instead of the Russian national anthem, a fragment of the concerto was used when these competing athletes were awarded a gold medal. Tchaikovsky’s Piano Concerto No. 1 has become one of the world’s most loved and recognized works in the entire orchestral repertoire. Its enduring beauty transcends us as only Tchaikovsky’s unmatched melodic talent can do.

“…YOU SEE, MY DEAR FRIEND, I AM MADE UP OF CONTRADICTIONS, AND I HAVE REACHED A VERY MATURE AGE WITHOUT RESTING UPON ANYTHING POSITIVE, WITHOUT HAVING CALMED MY RESTLESS SPIRIT EITHER BY RELIGION OR PHILOSOPHY. UNDOUBTEDLY I SHOULD HAVE GONE MAD BUT FOR MUSIC. MUSIC IS INDEED THE MOST BEAUTIFUL OF ALL HEAVEN’S GIFTS TO HUMANITY WANDERING IN THE DARKNESS. ALONE IT CALMS, ENLIGHTENS, AND STILLS OUR SOULS. IT IS NOT THE STRAW TO WHICH THE DROWNING MAN CLINGS; BUT A TRUE FRIEND, REFUGE, AND COMFORTER, FOR WHOSE SAKE LIFE IS WORTH LIVING”

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky

LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN

Symphony No. 3 in E-flat major, Op. 55 Eroica LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN

BAPTIZED: December 17, 1770, in Bonn, Germany DIED: March 26, 1827, in Vienna, Austria WORK COMPOSED: 1803 WORLD PREMIERE: April 7, 1805, in Vienna, Beethoven conducting PERFORMANCE HISTORY: Tonight marks the DSSO’s tenth performance of this symphony. The previous performances were in 1942 (Tauno Hannikainen conductor), 1957 (with Hermann Herz), 1968 and 1974 (with Joseph Hawthorne), 1985 and 1992 (Taavo Virkhaus), 2001 and 2005 (Markand Thakar), and on January 23, 2016 with Dirk Meyer. The 1992 performance was repated at Thorpe Langley Auditorium at UW-S and broadcast on Wisconsin Public Radio. The 2001 performance was on Markand Thakar’s first concert as DSSO’s Music Director.

INSTRUMENTATION: Two flutes, two oboes, two clarinets, two bassoons, three horns, two trumpets, timpani and strings. DURATION: 47 minutes.

After his return from Heiligenstadt in late 1802 Beethoven admitted that he was “not satisfied with the work I have done so far” and according to Carl Czerny he also said “from now on I intend to take a new way.” He decided to create an epic work and with his hearing deteriorating, he felt a sense of urgency to complete it. He chose a Promethean figure as the theme for this large symphony and the only living individual in Europe who Beethoven thought of as a benefactor of humanity was Napoleon Bonaparte. Napoleon, at that time, embodied Beethoven’s ideals of aesthetics, humanity and freedom. Beethoven was also inspired by the writings of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749-1832) and Friedrich Schiller (1759-1805), and he found that the image of the mythical Prometheus from the ballet he composed in 1801 represented Schiller’s “most perfectly appropriate symbol of assertion of one’s own freedom and regard for the freedom of others.”

Beethoven began his most concentrated work on Symphony No. 3 in May 1803 and it was his priority for that summer. This symphony would become a turning point not only in Beethoven’s career, but also in the history of music. He originally entitled the symphony Bonaparte, but by the following year Beethoven was so enraged when Napoleon proclaimed himself Emperor that he went to his completed score and tore the title page in half. He took the first page of the score and so violently scratched out the title that he wore a hole through the paper. He changed the title to Eroica (heroic), which is appropriate as it is bigger and longer than any previous symphony. It is also confrontational as it challenges us to explore the realm of the unconscious, and its scale is so unprecedented that it is still daunting for the first-time listener.

Very few works, such as Mozart’s The Marriage of Figaro, Wagner’s Tristan and Isolde, and Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring, share this remarkable impact on music history. Eroica is important not only for the new directions in music Beethoven was taking; it was a tool to make a political commentary on the state of the times. In it we begin to notice that there was a growing sense brewing in the populace of self-awareness and concern for the public good. At the 1805 premiere the reception was mixed. The listeners were not quite sure what to make of this new symphony. Some thought it too long or couldn’t understand its structure, while others felt it was a masterpiece. Eroica ushered in Beethoven’s middle period, also known as his ‘heroic’ period (roughly 1803-12), and it is likely that we would not have the works of Brahms, Tchaikovsky, Mahler, Shostakovich and others had Eroica not been composed.

Beethoven’s ability to improvise on themes of his own and others made him famous among the nobility in Vienna. His performances could go on for nearly an hour and they covered a wide range of emotions. In the first movement of Eroica Beethoven takes his listeners on a wild journey expressing life, wrong turns, confusion,

helplessness and despair, using only a few simple themes. The second movement takes on the most emotional extreme in life: Grief. Beethoven’s deepest crisis was the realization that he was going deaf. He described in his Heiligenstadt Testament the despondency he felt at the time. The fear that he was being cut off from people, losing the possibility of intimate conversations and becoming isolated filled him with terror. The Heiligenstadt Testament reveals Beethoven’s state of mind, which he inserts into the very fabric of his music.

The third movement scherzo represents a complete change from the darkness of the funeral march; despondency and fear is replaced with his hope for the future and exploring the joy of music. He has become very confident in his imagination, creating new musical worlds and personally communicating this optimism to the listener.

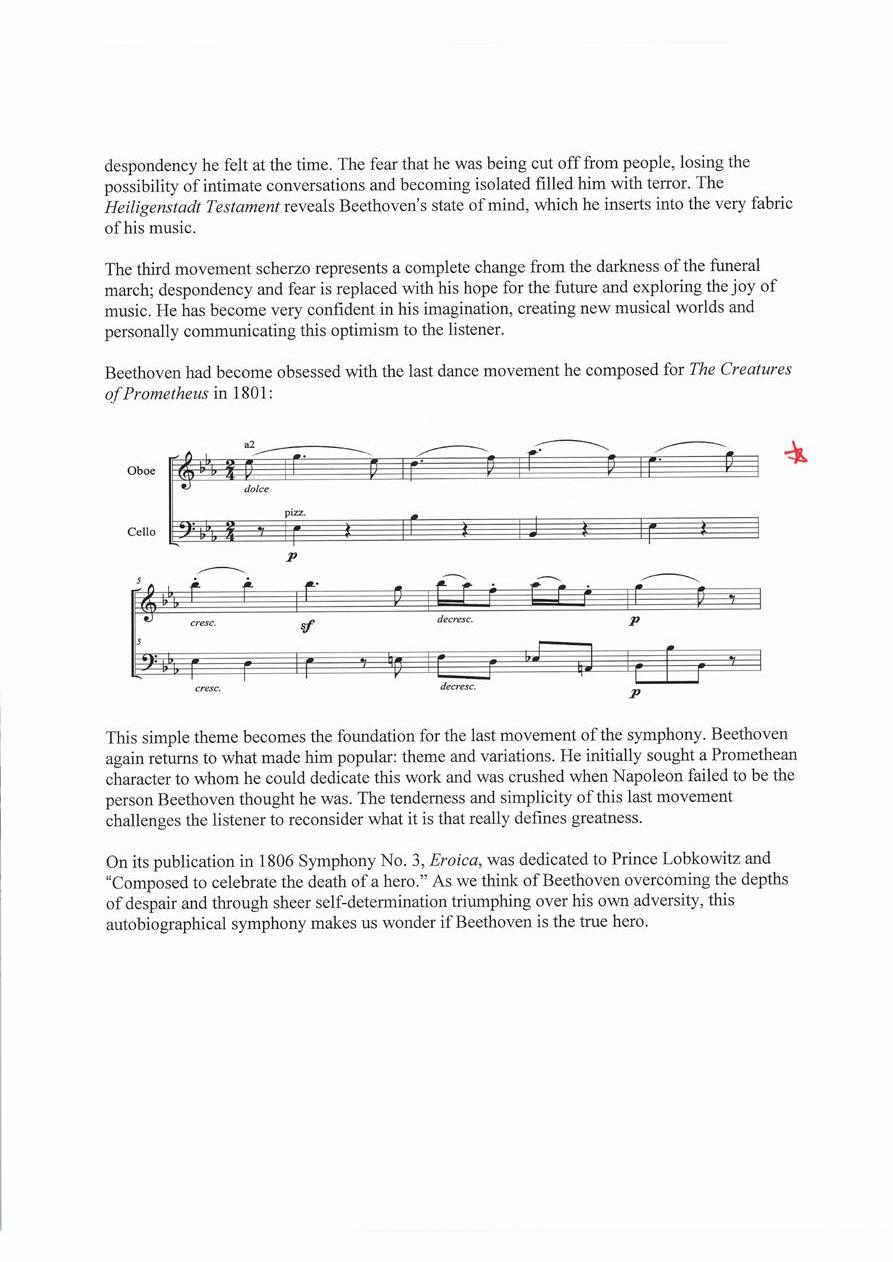

Beethoven had become obsessed with the last dance movement he composed for The Creatures of Prometheus in 1801:

This simple theme becomes the foundation for the last movement of the symphony. Beethoven again returns to what made him popular: theme and variations. He initially sought a Promethean character to whom he could dedicate this work and was crushed when Napoleon failed to be the person Beethoven thought he was. The tenderness and simplicity of this last movement challenges the listener to reconsider what it is that really defines greatness.

On its publication in 1806 Symphony No. 3, Eroica, was dedicated to Prince Lobkowitz and “Composed to celebrate the death of a hero.” As we think of Beethoven overcoming the depths of despair and through sheer self-determination triumphing over his own adversity, this autobiographical symphony makes us wonder if Beethoven is the true hero.

“SO HE IS NO MORE THAN A COMMON MORTAL! NOW, TOO, HE WILL TREAD UNDER FOOT ALL THE RIGHTS OF MAN, INDULGE ONLY HIS AMBITION; NOW HE WILL THINK HIMSELF SUPERIOR TO ALL MEN, BECOME A TYRANT!” Ludwig Van Beethoven