12 minute read

Masterworks 3 Program Notes

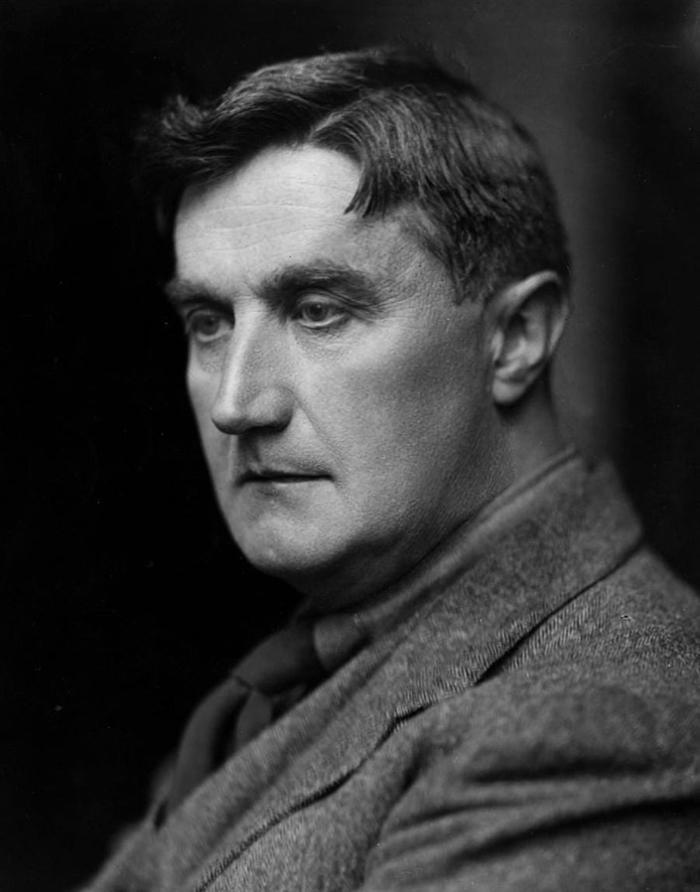

RALPH VAUGHAN WILLIAMS

BORN: October 12, 1872, in Down Ampney, Gloucestershire, England DIED: August 26, 1958, in London WORK COMPOSED: 1910 WORLD PREMIERE: September 6, 1910, in Gloucester Cathedral, London Symphony Orchestra, Vaughan Williams conducting PERFORMANCE HISTORY: This Vaughn Williams string orchestra piece has been played by the DSSO in 1953, 1962, 1973, and on October 14, 1994. The latter performance was conducted by Music Director candidate Richard Westerfield. The next day the concert was repeated in Aitkin, MN, but guest conducted by Delta David Gier. INSTRUMENTATION: : String Orchestra DURATION: 15 minutes

Ralph (pronounced rāf) Vaughan Williams was the most important English composer of his generation. His many works include operas, ballets, chamber music, secular and religious vocal pieces and orchestral compositions including nine symphonies. He was strongly influenced by English folk songs and Tudor music. He was a key figure in the 20th century revival of British music and his output marked a decisive break from the German-dominated style of the 19th century. Vaughan Williams came from a family of distinction and independence. His father, Reverend Arthur Vaughan Willams (1834-1875), was from a family of eminent lawyers. Sir Edward Vaughan Williams, the first Judge of Common Pleas, was the composer’s grandfather. Vaughan Williams’s mother, Margaret, née Wedgwood (1842-1937) was a descendant of Josiah Wedgwood and a niece of Charles Darwin. In 1875, after the death of her husband, Margaret moved her three children to her family home at Leith Hill Place, Surrey. Most of Vaughan Williams’ life was spent in this area or in London. He was encouraged to take an active interest in music and received his first lessons on the piano from a Wedgwood aunt. She also took him through The Child’s Introduction to Thorough Bass and a book on harmony. By the time Vaughan Williams attended preparatory school he was playing violin, piano and organ. He later switched to viola and played in the school orchestra while he was at Charterhouse (1887-1890). This was followed by two years at the Royal College of Music, then three at Trinity College, Cambridge (receiving a Bachelor of Music in 1894 and a Bachelor of Arts in history a year later), then returning for more study at the Royal College of Music.

Vaughan Williams had a rough beginning as a composer. His cousin, Gwen Raverat, recalled overhearing conversations about “that foolish young man, Ralph Vaughan Williams, who would go on working at music when he was so hopelessly bad at it.” The composer himself would later remark on his “amateurish technique,” which he said plagued him his entire life. As a young man it was apparent that Vaughan Williams was unable to see his own path in music. Further studies, with Max Bruch in Berlin and then Maurice Ravel in Paris, led him to recognize that he was attempting to imitate foreign models of music and that pointed him in the direction of using native resources for his inspiration. These interests were shared by Gustav Holst, who he met at the Royal College of Music in 1895, and they developed a close friendship until Holst’s death in 1934.

One of Vaughan Williams’s early and popular works is Fantasia on a Theme by Thomas Tallis, which he composed for the 1910 Three Choirs Festival (the oldest music festival in the world, beginning in 1715), held at Gloucester Cathedral. His biographer James Day called it “unquestionably the first work by Vaughan Williams that is recognizably and unmistakably his and no one else’s.” Thomas Tallis (c.1505-1585) was an English composer of High Renaissance music and is considered one of England’s greatest composers.

His compositions are primarily vocal and they occupy a primary place in the anthologies of English choral music. For his Fantasia, Vaughan Williams used one of the nine tunes Tallis wrote for the Psalter of 1567 of the Archbishop of Canterbury, Matthew Parker (1504-1575). It is from Psalm 2, which from the King James Bible begins, “Why do the heathen rage, and the people imagine a vain thing?” The metrical rendition by Parker is, “Why fum’th in sight: The Gentils spite, In fury raging stout? Why taketh in hond: the people fond, Vayne things to bring about?” Tallis’ tune is in the Phrygian mode, which is playing E to E on the piano and only using the white keys. Vaughan Williams’ setting is scored for a double string orchestra with string quartet. His biographer Michael Kennedy observes:

The spacious and sonorous use of spread chords, the majestic cadences and extreme range of dynamics, along with the antiphony between the two string bodies (playing alternately, the one answering the other, often like an echo), the contrast with the string quartet, and the passages for solo violin and solo viola combine to create a luminous effect.

The premiere of the Fantasia received a warm welcome, with few exceptions. J. A. Fuller Maitland wrote for The Times, “Throughout its course one is never quite sure whether one is listening to something very old or very new… But that is just what makes this Fantasia so delightful to listen to; it cannot be assigned to a time or a school, but it is full of the visions which have haunted the seers of all times.” Vaughan Williams’ Fantasia on a Theme by Thomas Tallis has become one of the most popular works in classical music.

EVENTS | WEDDINGS SENIOR GRADUATION FAMILY PORTRAITS

PHONE: 218-213-8618 WWW.ZENITHCITYPHOTOGRAPHY.COM

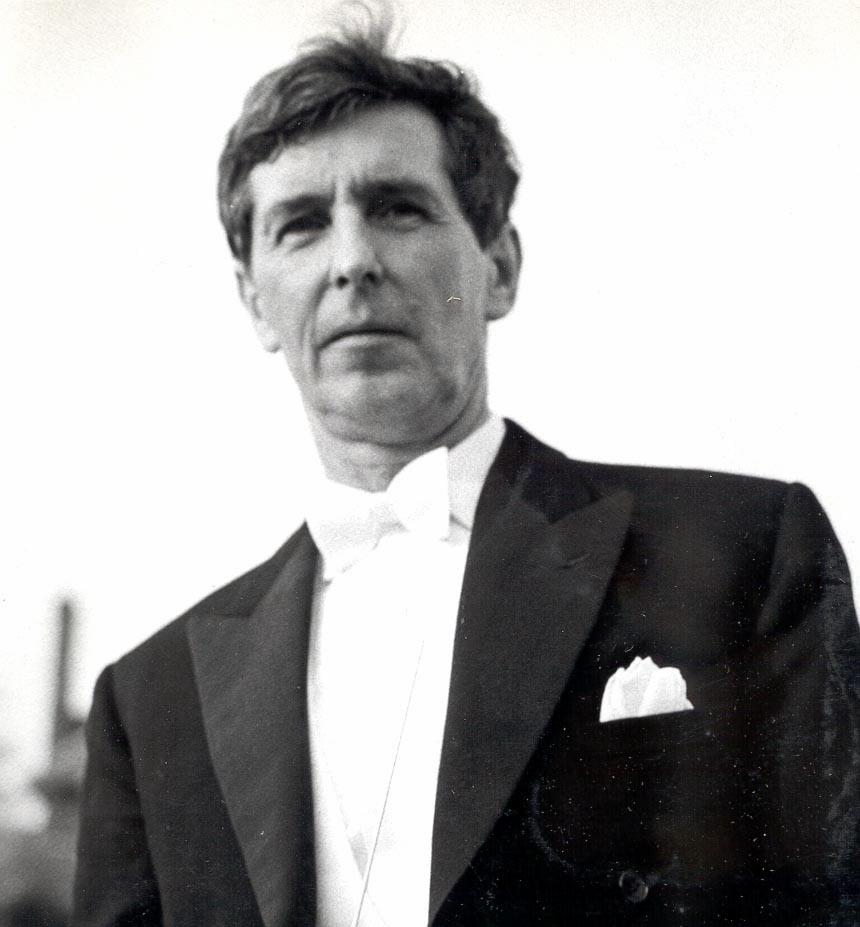

MICHAEL TIPPETT

A Child of Our Time MICHAEL TIPPETT

BORN: : January 2, 1905, in Eastcote, London, England DIED: January 8, 1998, in London WORK COMPOSED: 1939-41 WORLD PREMIERE: March 19, 1944, at the Adelphi Theatre, London; London Regional Civil Defence and Morley College Choirs with the London Philharmonic Orchestra, Walter Goehr conducting PERFORMANCE HISTORY: The performance of this choral work marks the first time the DSSO has given a performance of any music by Michael Tippett. INSTRUMENTATION: : Two flutes, two oboes and English horn, two clarinets, two bassoons and contrabassoon, four horns, three trumpets, three trombones, timpani, percussion (cymbals), strings, chorus, and soprano, mezzo-soprano, tenor and bass soloists. DURATION: 66 minutes

Sir Michael Kemp Tippett OM CH CBE, an English composer, rose to prominence during and immediately after World War II. During his life he was considered, along with Benjamin Britten (1913-1976), one of the leading British composers of the 20th century. Tippett had a slow start as a composer; he destroyed his earliest works and he was thirty before any of his works were published. His music was broadly lyrical until the mid1950s when he changed to a more experimental style. After his first visit to America in 1965, Tippett’s music began showing influences of jazz and blues. Around 1976, his later works returned to a more lyrical and melodic style. Tippett received many honors during his lifetime and the greatest praise was mostly for his earlier works.

Tippett briefly embraced communism in the 1930s and became a pacifist after 1940. In 1943 he was imprisoned for refusing to carry out war-related duties required by his military exemption as a conscientious objector. He was led to Jungian psychoanalysis in 1939 after experiencing difficulties in accepting his homosexuality. The Jungian dichotomy of shadow and light became a recurring factor in his music. While Tippett was in therapy he was also looking for a theme for a major work, an oratorio or opera, that would reflect both the turmoil in the world and his own recent catharsis. He based his work on a recent event: the murder in Paris of a German diplomat by 17-yearold refugee Herschel Grynszpan (1921, declared dead in 1960), who was a Polish Jew.

On November 7, 1938, Grynszpan entered the German embassy in Paris claiming to be a spy with important intelligence and saying he wanted to speak to the ambassador. The clerk on duty asked Ernst vom Rath (1909-1938), the junior of the two embassy officials available, to see him. When Grynszpan entered Rath’s office, Rath asked to see the intelligence documents and Grynszpan took out a gun and shot Rath five times. Right before shooting Rath, Grynszpan yelled that this was in the name of 12,000 persecuted Jews. Grynszpan made no attempt to resist and he confessed to shooting Rath, repeating his motive was to avenge the Jews persecuted by the Nazi regime. Hitler sent his two best doctors to Paris to try and save Rath’s life but the wounds were fatal and he died at 5:30 PM on November 9.

The Nazis used Rath’s assassination as a justification for their antisemitic pogroms and within hours the violent actions taken in Germany, known as Kristallnacht (Night of Broken Glass) began and lasted throughout the night and into the following day. More than 90 Jews were killed and over 30,000 arrested; the property damage was immense and although the Jews could file insurance claims Hermann Göring, who was in charge of German economic planning, ruled that the claims would not be paid. Kristallnacht shocked the world, triggering a new wave of Jewish emigration from Germany, and putting the world at the brink of war. Grynszpan was sent to Germany where there would be a trial and the expected outcome of guilty followed by an execution. The Justice Ministry in Germany, which

was not yet taken over by the regime, argued that because Grynszpan was not a German citizen, he could not be tried for a murder he committed outside of Germany, and because he was a minor he could not face the death penalty. There were also rumors of a homosexual relationship between Grynszpan and Rath that Goebbels and Hitler wanted to avoid becoming public knowledge. Even in Nazi Germany people fell through the cracks; Grynszpan spent the war in custody with reports of him dying in late 1942. Grynszpan’s parents had no communication from their son and they petitioned the German government to have him declared legally dead. Grynszpan was declared dead in 1960, with a date of death fixed at May 8, 1945. However a photo emerged in 2016, taken in 1946, of a man resembling Grynszpan participating in a demonstration by Holocaust survivors against British refusal to let them emigrate to the British mandate of Palestine. Facial recognition indicated a high probability that the man in the photo was Grynszpan.

Tippett chose this event for his oratorio A Child of Our Time, for which he also wrote the libretto. In its three parts Tippett deals with this incident in the context of the experiences of oppressed people, and offers the pacifist message of reconciliation and ultimate understanding. Similar to Handel’s Messiah, Part I is preparatory and prophetic, dealing with the general state of oppression in our time. Part II is narrative and tells of a particular story of a young man’s attempt to seek justice by violence and the catastrophic consequences, and Part III is meditative, questioning if there is a moral to be drawn. Because Tippett conceived the work as a general depiction of man’s inhumanity to man, he preserved the universality of the work by avoiding actual depictions of people or places. A very original feature of the work is the use of African American spirituals in place of chorales. Tippett justified their inclusion as they are songs born of oppression, which are not found in traditional hymns. He wrote to America for a collection of spirituals and found that there were several that fit with each key situation in his oratorio. He chose five: Steal Away; Nobody Knows the Trouble I See, Lord; Go Down, Moses; O, By and By; and Deep River. Tippett completed A Child of Our Time in 1941 on Easter and it was set aside with no immediate performance prospects because of the war. In February 1942 Tippett was charged with not complying with assigned non-combatant duties. There was a tribunal held and he testified that he rejected the duties because they were an unacceptable compromise with his principles. After several further hearings he was sentenced to three months’ imprisonment, of which he served two and was released. With encouragement from Britten, Tippett began to make arrangements for a premiere of A Child of Our Time. German composer and conductor Walter Goehr (1903-1960) agreed to conduct. Tippett recalled that “somehow or other the money was scraped together to engage the London Philharmonic Orchestra” (a major challenge because most of the musicians had left the city because of the war). The soloists were Joan Cross (soprano), Margaret MacArthur (alto), Peter Pears (tenor), and Roderick Lloyd (bass); and the Morley College Choir was augmented by the London Regional Civil Defence Choir.

Tippett’s biographer Oliver Soden writes of the premiere: It was an unusually cold March in 1944, and the West End theatres were barely heated. Concertgoers, many in army uniform, picked their way across the rubble and sandbags and craters of the Strand to the Adelphi Theatre, in order to hear a new work, for choir, orchestra, and four soloists, by a young composer called Michael Tippett. Orchestras had been evacuated from London, and concert halls were mounds of rubble; hence the decision to premiere the work in a theatre. But somehow, in that world of paper rationing and army calls-up, sheet music had been printed and performers drummed up. It was the midst of Operation Steinbock, known as the ‘Baby Blitz’, but on the day of the premiere, 19 March 1944, German bombers left London alone, turning their attention to the north of England. Theatre auditoriums during the war were hung with signs that would light up during an air-raid, in case the wail of the siren outside were drowned by the performance. But the premiere of Michael Tippett’s A Child of Our Time went without a hitch, and the next morning The Times hailed, in the tiny wartime newsprint that saved paper, ‘the choral work for which we have been waiting since the outbreak of this war’.

Tippett’s A Child of Our Time has not been performed often, possibly because of its premonitory quality. Addressing this situation, Tippett wrote in 1980 (a few years after the Pol Pot regime’s massacres in Cambodia): “When I wrote the work, I was so engulfed in the actions of the period, I never considered its prophetic quality. But it seems that the growing violence springing out of divisions of nation, race, religion, status, color, or even just rich and poor is possibly the deepest present threat to the social fabric of all human society.”