13 minute read

Masterworks 2 Program Notes

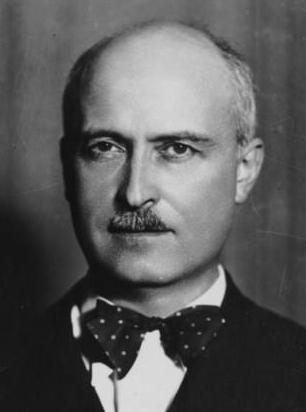

JACQUES IBERT

Hommage à Mozart JACQUES IBERT

BORN: August 15, 1890, in Paris, France DIED: February 5, 1962, in Paris WORK COMPOSED: 1956 WORLD PREMIERE: : 1956, Orchestra of the RTF (Radiodiffusion-Télévision Française), Eugène Bigot, conducting PERFORMANCE HISTORY: There have been no previous DSSO performances of this work. Other pieces by Jacques Ibert played by the Orchestra have been Escales (Ports of Call) in 1952 and 1982 and the Concertino da Camera with saxophone soloist Sigurd Rascher in 1955. The DSSO’s first Music Director Paul Lemay conducted our Youth Symphony in The White Donkey by Ibert on May 27, 1942. That was his last concert here. He entered World War II as a pilot and was missing in action in 1944. INSTRUMENTATION: Two flutes, two oboes, two clarinets, two bassoons, two horns, two trumpets, timpani and strings. DURATION: 5 minutes. Jacques François Antoine Marie Ibert was a prolific composer writing seven operas, five ballets, incidental music for plays and films, chamber music, piano, choral music. He is most known for his orchestral works, notably Escales (1922) and Divertissement (1930). Ibert’s compositional style can be best described as eclectic. His biographer, Alexandra Laederich writes, “His music can be festive and gay … lyrical and inspired, or descriptive and evocative … often tinged with gentle humour … all the elements of his musical language bar [except] that of harmony relate closely to the Classical tradition.” As an example, his composition Escales begins in the impressionist style of Debussy and within minutes sounds more like the Spanish composer Manuel de Falla, who was a distant relative of Ibert’s mother.

Ibert’s father was a successful businessman, and his mother a talented pianist. She encouraged her son to have a musical education and from the age of four, despite his father’s wishes that he go into business, he began studying the violin and then the piano. In 1910, Ibert attended the Paris Conservatoire, studying harmony, counterpoint and composition. He had private lessons with André Gedalge (1856-1926), whose other students included Nadia Boulanger, Georges Enescu, Maurice Ravel and Florent Schmitt. Ibert’s fellow students in these sessions included Arthur Honegger and Darius Milhaud.

His musical studies were interrupted by World War I, when he served as a naval officer. After resuming his studies, in 1919 he won the Conservatoire’s top prize (the Prix de Rome) at his first attempt. This prize gave him the opportunity to study in Rome and during that time he composed his first opera, Persée et Andromède (1921).

In 1956 Ibert was commissioned by the music department of Radiodiffusion-Télévision Française (RTF) to write a piece in commemoration of the bicentennial of Mozart’s birth. Ibert was a well-known Mozartean and this was the culmination of his lifelong emulation of the great genius. In Hommage à Mozart, Ibert uses Mozartean snippets that pop in and out of the texture featuring all the various sections of the orchestra. There are moments when he uses quotes from Mozart’s more famous works that will bring a smile when you recognize them. It is a truly delightful work that makes for a great opening to a concert.

FLORENCE BEATRICE PRICE

Violin Concerto No. 1 in D major (1939) FLORENCE BEATRICE PRICE (née SMITH)

BORN: April 9, 1887, in Little Rock, Arkansas DIED: : June 3, 1953, in Chicago, Illinois WORK COMPOSED: 1939 WORLD PREMIERE: : February 24, 2019, in Trenton, New Jersey; Samuel Thompson, New Jersey Capital Philharmonic, Daniel Spalding conducting PERFORMANCE HISTORY: The only other work by Florence Price the DSSO has given is her Piano Concerto in One Movement. Clayton Stephenson was the soloist on April 17, 2021, with Dirk Meyer conducting. This is the orchestra’s first performance of her Violin Concerto No. 1. INSTRUMENTATION: Two flutes, two oboes, two clarinets, two bassoons, four horns, two trumpets, timpani, strings and solo violin. DURATION: 24 minutes. Even today it is very difficult for a composer to have a work performed by a major symphony orchestra. However, a composer who is a woman and Black, in 1933… nearly impossible! The Chicago Symphony Orchestra premiered Price’s symphony in 1933 and a year later they premiered her Piano Concerto, with the composer at the piano. It appears that Florence Price was a major composer of the period and she had a busy schedule of writing orchestral music. She also developed a deep collaboration with contralto Marian Anderson, who in 1955 became the first African American soloist to perform at the Metropolitan Opera. At Anderson’s acclaimed Easter recital in 1939 at the Lincoln Memorial, she performed Price’s arrangement of the spiritual My Soul’s Been Anchored in the Lord. This propelled Price into the national spotlight and with Anderson’s support, Price and her daughters were finally able to be financially rewarded for her musical creativity.

The foundation of Price’s musical style is found in the genre of the African American spiritual. The New Orleans pianist Louis Moreau Gottschalk (1829-1869) was one of the first American composers to incorporate these elements in his compositions. In 1893 Antonín Dvořák was quoted in the New York Herald, “The future music of this country must be founded upon what are called Negro melodies. This must be the real foundation of any serious and original school of composition to be developed in the United States.” Price, along with William Grant Still and William Dawson, became a pioneer in integrating the passion and atmosphere of spirituals into classical symphonic form. Price wrote in an essay in 1938, “We are even beginning to believe in the possibility of establishing a national musical idiom.”

Although she continued to suffer challenges in having her music performed, Price continued composing until her sudden death in 1953. Most of her orchestral music was unpublished at this point. Her daughter, Florence Price Robinson, retained the manuscripts and had many difficulties in finding performance outlets for her mother’s music. Robinson died in 1975 and the manuscripts were presumed to be lost. Two property renovators discovered them in an abandoned house in 2009. The University of Arkansas at Fayetteville purchased the manuscripts and subsequently they were sold to G. Schirmer, Inc. Among the works discovered was her Violin Concerto No. 1, which was completed in December 1939.

The first movement opens in a style reminiscent of the great concertos of Tchaikovsky and Brahms, all sharing the key of D major. All this changes when the soloist enters with the theme that employs gentle syncopations and her exploration of ‘blue notes’ (flatted third and seventh degrees of the major scale). This is idiomatically similar to her other symphonic works, as well as those of Still and Dawson. The accompaniment throughout the movement is distinctly organ-like, employing different combinations of instruments in sustained tones to provide a unique timbral foundation for the soaring melodies of the solo violin. She draws some of the syncopated motives from the first movement for her main theme in the second movement. These motives are traded around the orchestra as the underpinning for the expansive, lyrical melody of the solo violin. The middle section is an undulating interlude which showcases the soloist. The third movement is a tour-de-force that demands much from both the orchestra and soloist. Price uses more chromaticism and dissonance in this movement, similar to the modern works of the time. The overall character is similar to the finale of Samuel Barber’s violin concerto, which was composed in the same year. After a false ending, the movement comes to a brilliant close.

Price’s Violin Concerto No. 1 was never premiered in her lifetime. Indeed, the work has only been in the public since 2018 when violinist Er-Gene Kahng made the first recording of the work with the Janaček Philharmonic, conducted by Ryan Cockerham, for Albany Records (TROY1706). Only a small number of performances have been made of the work since the premiere recording. The first documented performance is with violinist Samuel Thompson on February 24, 2019, with the New Jersey Capital Philharmonic under the direction of Daniel Spalding. Peter Clarke performed it for the inaugural concert of the 2019-20 season of the La Jolla Symphony under the direction of Steven Schick (a live recording is available on YouTube). On February 20-21, 2020, violinist Bella Hristova (our soloist this evening) performed it with conductor Adam Demirjian and the Knoxville Symphony Orchestra. The first performances by a major symphony orchestra were on October 6-7, 2022, with soloist Randall Goosby and the Philadelphia Orchestra under the direction of Yannick Nézet-Séguin.

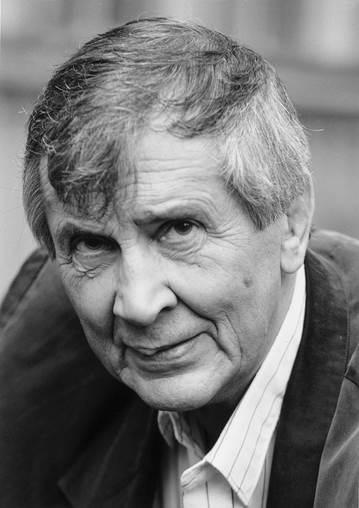

EINOJUHANI RAUTAVAARA

Cantus arcticus (Concerto for Birds and Orchestra) EINOJUHANI RAUTAVAARA

BORN: October 9, 1928, in Helsinki, Finland DIED: July 27, 2016, in Helsinki WORK COMPOSED: 1972 WORLD PREMIERE: October 18, 1972, Arctic University of Oulu, Finland; Oulu Symphony Orchestra, Stephen Portman conducting PERFORMANCE HISTORY: Tonight marks the Orchestra’s first performance of any music by Rautavaara. INSTRUMENTATION: Two flutes, two oboes, two clarinets, two bassoons, two horns, two trumpets, trombone, tape recorder, timpani, percussion (cymbals, tam-tam), harp, celesta and strings. DURATION: 18 minutes

Einojuhani Rautavaara is among the most notable Finnish composers since Jean Sibelius. He composed a great number of works spanning various genres, including eight symphonies, nine operas, thirteen concertos and numerous works for various ensembles. His father, Eino, was an opera singer and cantor. His mother, Elsa, was a doctor and she encouraged him to learn the piano when he was young. When Einojuhani was ten years old his father passed away and less than six years later his mother died. He then went to live with his aunt, Hilja Teräskeli, in Turku, where he began formal piano lessons at the age of seventeen.

Rautavaara went on to study piano and musicology at the University of Helsinki and from 1948 to 1952 he studied composition at the Sibelius Academy under Aarre Merikanto (1893-1958). In 1954 Rautavaara won the Thor Johnson Contest for his composition A Requiem in Our Time. Jean Sibelius selected him in 1955 to receive a Koussevitzky Foundation scholarship, which Rautavaara used to study with Vincent Persichetti (1915-1987) at the Juilliard School. During the following two years he also studied with Roger Sessions (1896-1985) and Aaron Copland at Tanglewood. Rautavaara dedicated his 1980 concerto for the double bass, Angel of Dusk, to Olga Koussevitzky, the widow of Serge Koussevitzky, the founder of Tanglewood. He returned to Helsinki and graduated from the Sibelius Academy in 1957. From 1976 to 1990 he was professor of composition at his alma mater where some of his more famous pupils were composer Kalevi Aho (b. 1949) and conductor Esa-Pekka Salonen (b. 1958).

Cantus arcticus was commissioned by the Arctic University of Oulu in 1972 for its first doctoral degree ceremony. Oulu is a coastal city near the northern end of the Gulf of Bothnia that separates Finland from Sweden. Some of the bird songs were recorded near Oulu, others around the Arctic Circle and the marshlands of Liminka. The work is in three movements, each of which features a different set of bird songs. The first movement, Suo (The Marsh or The Bog), opens with two solo flutes in an impressionistic melody that is later joined by other woodwinds and a recording of bog birds in springtime. The repeated dissonant calls from the oboes and trumpets create a sense of spatial distance. The second movement, Melankolia (Melancholy), begins with two shore larks calling back and forth to one another, the recording is lowered in pitch by two octaves. The texture of the strings creates a meditative space so the focus can be on the dialogue between the birds. The final movement, Joutsenet muuttavat (Swans Migrating), opens with the chaotic sound of a large group of swans. Rautavaara uses this recording as an accompaniment to the orchestra mimicking their movement instead of their voices. He divides the orchestra into four groups: 1. violins and violas; 2. woodwinds; 3. horns, cellos and basses; and 4. celesta and harp. These four groups occupy the same space, overlapping and not perfectly in synch, but not colliding with each other. Imagining a flock of geese, flying at slightly different speed, will give a sense of how the instrumental parts might appear visually. There is one long crescendo throughout the movement and after its climactic moment, the swans fade into the distance.

I believe that this quote by Rautavaara really sums up the importance of art: “It is my belief that music is great if, at some moment, the listener catches ‘a glimpse of eternity through the window of time.’ This, to my mind, is the only true justification for all art. Everything else is of secondary importance.”

See the whole picture

Weis Eye Center is the only Practice in the Northland to offer blade-free z-Lasik surgery.

Call (218) 625 1917 www.weiseyecenter.com

WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART

Symphony No. 36 in C major, K. 425 Linz WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART

BORN: January 27, 1756, in Salzburg, Austria DIED: December 5, 1791, in Vienna WORK COMPOSED: 1783 WORLD PREMIERE: : November 4, 1783, in Linz, Austria PERFORMANCE HISTORY: Surprisingly, there have been no previous DSSO performances of this Mozart symphony.

INSTRUMENTATION: Two oboes, two bassoons, two horns, two trumpets, timpani and strings.

DURATION: 26 minutes.

Throughout Mozart’s short life he suffered what we would now call Helicopter Parent Syndrome. His father, Leopold, was overbearing and it seemed that nothing would please this curmudgeon. Around mid-1781 Mozart was in Vienna and he moved into the house of the Webers, family friends from Mannheim now living in Vienna. Only a short time later did Mozart move again to put a stop to rumors of his affair with the Weber’s third daughter Constanze. Nevertheless, the affair continued and they planned to be married (most likely pressure from the future in-laws). On July 31, 1782, Mozart wrote to his father asking for his approval, on August 2 the couple took communion together, on August 3 the marriage contract was signed, and on August 4 they were married. Leopold’s grudging consent arrived on August 5.

Leopold did not accept Constanze as his daughterin-law and he wasn’t silent about it. After a year of postponed attempts to visit his insufferable father in Salzburg and heal this situation, Mozart and Constanze eventually set out from Vienna in July 1783. They remained in Salzburg for about three months and later correspondence suggests that the visit was not entirely happy. Mozart wanted nothing more than to please his father, but it was an exercise in futility; Leopold was not impressed with Constanze and this would plague Mozart the rest of his life.

On their return journey to Vienna the couple were met at the city gates of Linz by a servant of Count Johann Thun-Hohenstein, an old friend of the Mozart family. After learning that a concert was arranged to take place the following Tuesday, November 4, Mozart wrote to his father that he had no symphony with him and that he had to “work on a new one at head-overheels speed.” He composed the Linz Symphony in four days, beginning after his arrival in Linz at 9:00 AM on October 30 and having it ready for Count Thun’s orchestra to perform it on November 4.

Since his relocation to Vienna in early 1781, Mozart most likely gained considerable confidence in his compositional abilities. His bold use of a slow introduction to the first movement, a rarity at that time, is evidence of Mozart exploring his own personal style. He also used a slow introduction to the first movements in his next two symphonies, 38 and 39 (Symphony No. 37, for which Mozart wrote the introduction, was actually written by Michael Haydn (1737-1806). The first and last movements are operatic in style and influenced by his hugely successful opera Die Entführung aus dem Serail, that was composed shortly after his arrival in Vienna. Although Mozart composed this entire symphony in just four days, it is a fully finished work that holds its own in comparison to his other symphonies of the same period. He wrote in the score that the last movement should be played “as fast as possible,” thus bringing a hastily composed Symphony No. 36 to a breathtaking finish.